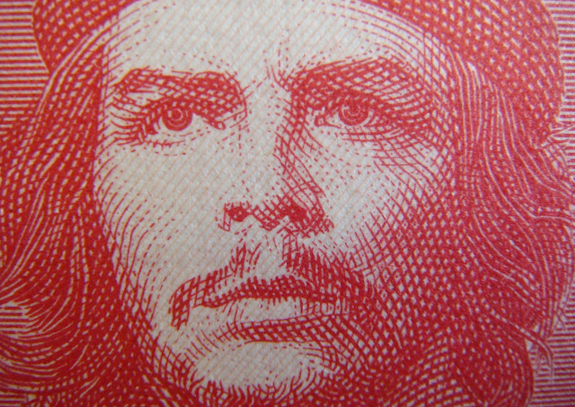

Che and the CIA in Bolivia

Why did Che choose Bolivia? Landlocked, Bolivia was Latin America’s poorest, most illiterate, most rural and most Indian country. It was also the most unstable country in Latin America, having gone through more than 190 changes in government since it became an independent republic in 1825. Like Mexico in the years 1910 to 1920, and Cuba more recently, Bolivia was a Latin American country whose revolution in 1952 was based on popular participation. And, of course, Bolivia is a neighbor to Che’s home country of Argentina.

Constantio Apasa, a Bolivian tin miner, summed up the political situation in his country in the year that Che arrived: “When the MNR (Revolutionary Nationalist Movement) came to power in 1952, we felt it was a workers’ party and things would be different. But then the MNR politicians organized a secret police and filled their pockets. They rebuilt the army which we had destroyed, and when it got big enough, the army threw them out. Now the army has new weapons which we cannot match.” The 1964 military coup ended the MNR’s twelve-year reign. The military officers who now ran Bolivia were all U.S.-trained.

Che arrived in Bolivia via Uruguay in early November of 1966 disguised as a Uruguayan businessman. So deceptive was his appearance—shaved beard, horn-rimmed glasses, tailored bank suit—that Phil Agee, the CIA agent in Uruguay charged with finding Che and who would later quit the agency and become a supporter of the Cuban Revolution, wrote that Che easily avoided Uruguayan officials despite a warning leaflet Agee had prepared and passed out at the airport in Montevideo. In fact, Fidel told author Ignacio Ramonet that even Raul Castro failed to recognize Che upon meeting him before he left Cuba for Bolivia.

Che’s plan was to set up a camp for his guerrillas and, once they were trained, move his troops north to engage the weak Bolivian Army. On November 7, 1966, Che arrived at the guerrilla base on the Nacahuazu River in Bolivia. It is the first date in Che’s Bolivian Diary, and opens with: “Today begins a new phase. We arrived at the farm at night. The trip went quite well.” They were to train for approximately four months before engaging in battle. We have no U.S. government documents from roughly the day Che arrived in Bolivia until some four months later. It seems probable that the U.S. did not know his whereabouts during this time. We have used Che’s diary to fill in this gap.

What follows are shortened versions of Che’s monthly summaries for November, December, January, and February, 1967. During this period the guerrillas were training, scouting terrain, and preparing themselves for battle. Che was holding secret meetings with Mario Monje, head of the Communist Party of Bolivia, who ultimately refused to support the expedition. Che noted in his diary that “the party is now taking up ideological arms against us.”

At the end of November Che writes: “Everything has gone quite well; my arrival was without incident…The general outlook seems good in this remote region… ” By the end of December, “the team of Cubans has been successfully completed; morale is good and there are only minor problems. The Bolivians are doing well, although only few in number.”

At the end of January: “Now the real guerrilla phase begins and we will test the troops; time will tell what they can do and what the prospects for the Bolivian revolution are. Of everything that was envisioned, the slowest has been the incorporation of Bolivian combatants.”

On February 1, Che took most of the men on what was supposed to be a two-week training mission. It turned into an almost fifty-day ordeal in which two of the Bolivians drowned. At the end of February, while still on the training mission, Che wrote: “Although I have no news of what is happening at the camp, everything is going reasonably well, with some exceptions, fatal in one instance… The next phase will be combat, and will be decisive.”

General Tope was afraid Barrientos would indiscriminately bomb civilians, which he believed would be counterproductive.

By the middle of the following month things had stopped “going reasonably well.” On March 16, three days before Che and his guerrillas returned to the camp, two men, Vicente Rocabado Terrazas and Pastor Barrera Quintana, deserted from the party that had been left behind. They were picked up and interrogated by the Bolivian authorities. They gave information about the guerrillas and their location. As a result, the police raided a farm where some of the guerrillas were stationed. From then on, Che and his guerrillas were effectively on the run. The Bolivian army was scouring the area, and those who had stayed behind saw a plane circling above the area over a period of days.

The report from the deserters caused alarm at the highest levels of the Bolivian government, as is set forth in a Department of State telegram to the Secretary of State and others from the U.S. Ambassador to Bolivia, Douglas Henderson. Henderson had been ambassador to Bolivia since 1963, a year before the Bolivian revolution was overthrown in 1964. He was a career foreign-service officer whose father had joined the U.S. Army and helped put down the Philippine insurrection of 1899-1902, as well as the Mexican Revolution in 1916. Henderson’s telegram describes a meeting held on March 17th. The meeting was between President Barrientos, his acting chief of the armed forces and other Bolivian military officials on the one side, and on the other side, Henderson, his deputy chief of mission and the defense attaché.

The subject of the memo is “Reported Guerrilla Activity in Bolivia.” It opens with a reference to a phone call to the ambassador. “At the urgent request of President Barrientos, I called on him at his house this afternoon.” In substance, Henderson’s telegram reports the capture of the two deserters, their admitted association with about forty guerrillas, and their location. The deserters said they were led by Castroite Cubans and the contingent included other nationalities. The two men mentioned Che Guevara as the leader but admitted they had never seen him. Both Henderson and Barrientos were doubtful of Guevara’s presence. Barrientos “requested immediate assistance, especially radio locating equipment to help pinpoint reported guerrilla radio transmitters.” Henderson responded by making no commitments and telling Washington that “We are taking this report of guerrilla activity with some reserve.” But he said he would try and furnish the radio equipment locally before asking for further help.

Barrientos had come to power in the typical Bolivian manner: The democratically elected government of Victor Paz Estenssoro was overthrown in November of 1964 by a U.S.-supported coup, which Barrientos led. The CIA and the Pentagon wanted Paz out. In 1964, Paz had voted to keep Cuba in the Organization of American States and against the U.S.-sponsored OAS sanctioning of Cuba, refusing to break relations between his country and the beleaguered island. Che called the OAS the “Ministry of Colonies.” Barrientos had trained in the United States and had a close relationship with both the CIA and the American military. His friend and flight instructor while he trained in America was Colonel Edward Fox, who was the military attaché at the American embassy in La Paz in 1964. At that time Fox worked for the CIA.

Twenty of the twenty-three top Bolivian military men now running the country were trained by the United States at the School of the Americas, then in the Panama Canal Zone, as were 1,200 officers and men in the Bolivian armed forces. The School of the Americas trained and indoctrinated so many Latin American military men it was known throughout Latin America as the Escuela de Golpes (Coup School). Recent events in Vietnam were very much on Ambassador Henderson’s mind, and he was wary of Barrientos. He stood for a more measured response to the guerrillas than the hard-line approach suggested by the Bolivian president. He believed that “overkill” could easily make the Bolivian peasantry into durable enemies of the United States.

In a survey of instability across Latin America in 1965, the CIA ranked Bolivia second only to the Dominican Republic, which they were to invade that year. The Agency was afraid that the political turmoil in Bolivia could lead to communists toppling Barrientos. Through Henderson, Barrientos requested that the United States provide the Bolivian army with high-performance aircraft and napalm as well as the radio locators. He also asked Henderson to warn the governments of Paraguay and Argentina about the guerrilla threat, which he did. However, on Henderson’s advice, the U.S put off supplying aircraft and napalm, fearing that their use would likely prove counterproductive by turning the peasantry toward Che.

On March 19, Che arrived back at the guerrilla’s base camp after the lengthy training mission that had gone awry. Upon his return he received the bad news about the two desertions. Che, too, had seen a plane circling the day before and was concerned. He was told the news that the police had raided the farm and that the army could be advancing against them.

He met with Tania Bunke, the undercover operative who had been sent to La Paz two years earlier as support for Che, who had arrived at the camp during his absence. Tania was thirty-two years old and had grown up in Argentina, where her parents were refugees from Nazi Germany. Her father, a language teacher, was German; her mother was a Russian Jew. Both were Communists. Tania first met Che in 1959 when he led a delegation to East Germany and she was a philosophy student at Humboldt University in East Berlin. She moved to Cuba two years later where she attended the University of Havana, worked in the Ministry of Education, and joined the Cuban Women’s Militia before leaving for Bolivia.

Tania had arrived at the camp in February along with Regis Debray and Ciro Bustos. Debray was to have been Che’s courier to Havana and then to Paris. He came from an upper-class Parisian family and had attended the prestigious École Normale Supérieure. Debray had recently taught philosophy in Havana and had written the widely read book Revolution in the Revolution, which laid out what became the Fidelista theory of revolution—small groups of guerrillas operating in the countryside and linking with supporters in the cities in a way that provided a catalyst for the seizure of power. The Leninist concept of building a mass socialist party was discarded. Debray popularized Guevara’s argument that such a party was not necessary at this late stage of imperialism. In situations such as Bolivia where the government and its army were extremely weak and the American military stretched thin with 500,000 troops bogged down in Vietnam, a rural guerrilla force with support in the urban areas could come to power without building a party of the Leninist type. This is what, Guevara argued, had happened in Cuba.

Tania had arranged false documents for Debray and Bustos, an Argentinian artist and an early supporter of the Cuban revolution who had travelled to Cuba in 1960, met Che, and collaborated with him in organizing support for revolutionaries in Uruguay before going to Bolivia. Despite Che’s orders to the contrary, Tania had herself accompanied the men from La Paz to the Camiri guerrilla camp. While she waited for Che, her jeep was discovered by the Bolivian army. It tied her to both the guerrillas and the support network in La Paz. Che wrote: “Everything indicates that Tania has become known, which means that two years of good patient work has been lost. Departure has become very difficult now.”

Debray was beaten with a hammer. Bustos confessed when shown photos of his daughters. A CIA agent aided the interrogations.

A few days after Che’s return to the base camp, early on the morning of March 23, 1967, the guerrillas fought their first battle. Che had sent out some of his men to set up a defensive perimeter. In the course of doing so they sprung an ambush on a group of Bolivian soldiers, killing seven and capturing eighteen. As Che reports, “Two prisoners—a major and a captain—talked like parrots.” After this battle, it was obvious to Che that his general whereabouts had been discovered. This meant he and his men had to stay on the move.

A U.S. Department of Defense Intelligence Information Report dated March 31, 1967, on the subject of counterinsurgency capabilities in Bolivia reports in detail on this March 23 battle. “After diminishing reports of guerrilla activity during the weekend of 17th-21st March 1967, on March 23rd a Bolivian army patrol clashed with a guerrilla group ranging in reported numbers from fifty to four hundred. This action occurred in Nancahausu (1930S/6340W)… They are a well organized force and are armed with modern weapons and under the direction of Castroite Cubans… The Bolivian Army has approximately six hundred men involved at the present time… They are being supported by the Air Force… ”

The success of Che’s forces caused alarm to Bolivian officials. On the day of the battle, Barrientos had another meeting with the U.S. Deputy Chief of Mission advising him that the guerrilla situation had worsened, and that he believed the guerrillas were, “Part of a large subversive movement led by Cuban and other foreigners.” Barrientos said his troops were “green and ill-equipped” and asked again for urgent U.S. assistance. The recent attacks led the U.S. officials to believe that the guerrillas “could constitute potential security threat to the Government of Bolivia.” This Intelligence Information Report also points out that “the United States is the only foreign country providing military assistance and hardware to Bolivia.”

Henderson and Barrientos met again on March 27, 1967. In a one-and-a-half-hour meeting Barrientos appealed for direct U.S. aid to support the Bolivian armed forces so they could meet the “emergency” in which Bolivia was “helping to fight for the U.S.” The Department of State responded to Henderson by saying it was reluctant to support a significantly enlarged army, but would provide a “limited amount of essential material to assist a carefully orchestrated response to the threat.” If that proved inadequate, Henderson was to assure Barrientos that the U.S. would consider further requests for help. On March 31, 1967, the Department of State informed U.S. embassies in neighboring countries that the plan was to “block the guerrilla escape, then bring in, train and prepare a ranger-type unit to eliminate the guerrillas.” Further, the Department of State was considering using a special U.S. Military Training Team, “for accelerated training [of the] counter-guerrilla force.”

In reporting on this meeting, Henderson noted the sad state of the Bolivian armed forces: “I suspect that Barrientos is beginning to suffer some genuine anguish over the sad spectacle offered by the poor performance of his armed forces in this episode; i.e., an impetuous foray into reported guerrilla country, apparently based on a fragment of intelligence and resulting in a minor disaster, which further tended to panic the GOB into a lather of ill-coordinated activity, with less than adequate professional planning and logistical support.”

Che’s analysis in his diary entry at the end of March included, among other points, an assessment of the overall situation: “General panorama is characterized as follows: The phase of consolidation and purging of the guerrilla force—fully completed. The initial phase of the struggle, characterized by a precise and spectacular blow [the battle of March 23, 1967], but marked by gross indecision before and after the fact [bad conduct and missed opportunities by two of the guerrillas] ….” He concluded that “evidently, we will have to hit the road before I expected and move on, leaving a group to recover, saddled with the burden of four possible informers. The situation is not good, but now begins a new testing phase for the guerrilla force that will be of great benefit once surpassed.”

General Tope proposed to General Ovando that the United States train a Bolivian battalion whose mission would be to exterminate Che’s guerrillas.

On April 10, the guerrillas again engaged in two ambushes, in which a total of eight Bolivian soldiers were killed, eight wounded, and twenty-two or twenty-eight (the diary is unclear) taken prisoner. One of Che’s men was killed. On April 17, Che split up his group. Tania and another guerrilla were ill and they, along with some other stragglers, were left with Joaquin (Major Juan Vitalio Acuña, a commandante in the Revolution) while Che and the remaining guerrillas went off. The two parties were never to meet up again.

After the discovery of the guerrillas in March, American General Robert W. Porter, chief of the Southern Command, went to Bolivia to assess the situation. Other American generals and admirals made some half dozen visits between March and Guevara’s death in October. On April 18, General Porter sent Air Force brigadier William A. Tope to Bolivia to make a full report on the guerrilla situation and the help that the Bolivians needed. He stayed through April 30, and met three times with Barrientos and also with Air Force General Ovando.

The Bolivian military was very weak, and both Che and the Americans knew it. General Tope, after meeting with Barrientos, wrote a report that was sent to American President Lyndon Johnson’s Latin American advisor Walt Whitman Rostow. Tope reported that the Barrientos and Bolivian high command wanted fighter planes and napalm. Tope believed that the thinking of the Bolivian generals was “archaic, impulsive, and self-aggrandizing.” He, like Henderson, was afraid that Barrientos would indiscriminately bomb civilians, which he believed would be counterproductive.

General Tope proposed to General Ovando that the United States train a Bolivian battalion whose mission would be to exterminate Che’s guerrillas. Ovando was enthusiastic. As a result, on April 28, while Tope was still in Bolivia, the United States Military Advisory Group signed an agreement with the Bolivian government providing training and equipment to the Bolivian army. The entire document, entitled “Memorandum of Understanding Concerning Activation, Organization and Training of the Second Ranger Battalion-Bolivian Army,” is reproduced in our book.

The agreement opens with a recognition of a “possible threat to the internal security of the Republic of Bolivia in the Oriente,” and agrees that “a rapid reaction force of battalion size capable of executing counterinsurgency operations in jungle and difficult terrain throughout this region will be created in the vicinity of Santa Cruz, Republic of Bolivia.” The Bolivian Generals agreed “to furnish the troops and a suitable place to have them trained.” The Americans agreed to supply and train them and provide intelligence. They promised to send sixteen American officers whose mission would be to “…produce a rapid reaction force capable of counterinsurgency operations.”

The Americans quickly put in place the intelligence network promised in the agreement, something badly needed by the Bolivians. General Tope reported that “the Bolivians’ armed forces do not have a sound, or even workable intelligence system.” This was because the Bolivian army had been dismantled after the 1952 revolution and was only reconstructed beginning in 1964 with the ascendancy of the military dictatorship. Tope sent U.S. Air Force General William K. Skaer, his head of intelligence in Panama, to Bolivia to set up the network. Hector Maloney, a CIA officer, assigned to Porter’s command, was also sent to help Skaer get things started.

On April 20, a week prior to the signing of the Memorandum of Understanding, Regis Debray and the Argentinean Ciro Bustos left the guerrillas’ camp along with the journalist George Andrew Roth. Roth had tracked down the guerrillas and may have been a collaborator with the CIA. Debray knew nothing of this possible involvement. Debray thought, wrongly, that he and Bustos could pose as journalists too. Their plan did not work, and upon walking into a village on the same day they had left Che, Debray, Bustos and Roth were captured by the Bolivian Army. Their quick capture and the fact that Roth was released in July before the others lends credibility to the assertion that Roth was indeed working with the CIA. Debray and Bustos were tortured. Debray was beaten with a hammer. Bustos confessed when shown photos of his daughters. They admitted that Che was in Bolivia, providing solid confirmation, for the first time, of what the American and Bolivian governments suspected. Bustos even provided accurate hand-drawn portraits of the guerrillas. A CIA agent, a Cuban American code-named Gabriel Garcia Garcia, aided the interrogations.

The Green Berets trained the Bolivians to operate in units divided into platoons, companies, and finally the battalion.

The summary of activity in April appearing in Che’s diary is that “things are developing normally,” but “we are totally cut off,” “[the] peasant support base has yet to develop,” and “there has not been a single new recruit.” Regarding the military strategy, Che emphasizes that “It seems certain the North Americans will intervene heavily here, having already sent helicopters and apparently the Green Berets, although they have not been seen around here.” Che concludes that “morale is good among all combatants who have had their preliminary test as guerrilla fighters.”

On May 8, pursuant to the Memorandum of Understanding, sixteen Green Berets arrived in Bolivia to train the Bolivian Second Ranger Battalion, which had been set up to track down and eliminate the guerrillas. The Green Berets had been created by President John F. Kennedy after the failure of the Americans at the Bay of Pigs to operate as a force for international counterinsurgency. The group in Bolivia was under the leadership of an officer named Ralph “Pappy” Shelton. A career soldier, Shelton came from an impoverished family and had only a tenth-grade education. He had been wounded in Korea before going to Officers Candidate School where promising soldiers are trained to be officers. He then fought in Vietnam and Laos. Shelton arrived in Bolivia from Panama the second week of April 1967. The training lasted until September 19.

The Green Berets trained the Bolivians to operate in units divided into platoons, companies, and finally the battalion. They were taught how to march, shoot, detect booby traps, fight hand-to-hand, deal with barbed wire, and to move around at night. They built themselves up physically and practiced firing at targets. It was particularly important to teach them how to avoid ambushes. Shelton himself was reportedly very popular with local civilians. He made a point out of socializing and would visit local bars and play his guitar.

Meanwhile, also on May 8, Che’s guerrillas mounted another ambush of Bolivian soldiers, killing three and taking ten prisoners, along with some rifles, ammunition and food. The next morning they set the soldiers free.

On May 11, Walt Rostow wrote a letter to Johnson reporting that “the first credible report that ‘Che’ Guevara is alive and operating in Latin America,” had been received, but that “[w]e need more evidence before concluding that Guevara is operational—and not dead… ” The information probably had come from the interrogation of Bustos and Debray, or from the guerrillas captured in Bolivia.

At the end of May, Che summarized his situation in his diary. Most significantly, he wrote that there now was a “total lack of contact with Manila (Havana), La Paz, and Joaquin, which reduces the group to twenty-five.” This situation was only to get worse.

CIA Agents Disguised as Bolivian Soldiers

In light of information from the interrogations of captured guerrillas, and especially the information given by Debray and Bustos, the United States stepped up its efforts to implement the April agreement with the Bolivians. By mid-to-late June the U.S. had recruited two Cuban Americans who would wear Bolivian military uniforms, blend in with the Bolivian soldiers and accompany the Bolivian Ranger Battalion as they sought to eliminate the guerrillas. One was Gustovo Villoldo, known in Bolivia under the alias Eduardo Gonzalez.

Villoldo, a Miami counter-revolutionary who had fought in the Bay of Pigs and whose wealthy father had owned a car dealership in Havana before the revolution, was hired by the CIA to set up an intelligence network in Bolivia. Earlier in his career he had been sent by the CIA to the Congo with a group of Cuban counter-revolutionaries to help the Tshombe government to fight the Castroists who were there. He had known Che was in the Congo.

Villoldo first arrived in Bolivia in February, 1967 and returned there in July. In an interview in Miami on November 21, 1995, he told Jose Castaneda that “We placed a series of assets and those assets began giving us information we needed to neutralize (the uprising). That entire mechanism, that logistical support… left the guerrillas completely isolated. We completely penetrated the urban network.”

In 1961, at the age of twenty-one, Rodriguez volunteered to assassinate Fidel Castro.

Serving under Villoldo was the second Cuban American employed by the U.S.: CIA agent Felix Rodriguez, who went on to become well known as a result of his claim to be the highest-ranking military officer on the scene when Che was executed. Rodriguez’s 1989 autobiography is titled, with characteristic bravado, Shadow Warrior: The CIA Hero of a Hundred Unknown Battles. In it, he recounts how he grew up as the only child of a well-to-do provincial Cuban family of Spanish/Basque ancestry. One of his uncles was a minister in the Batista government, another was a judge. He spent time at the farm of his uncle, Felix Mendigutia, where he rode horses and, at the age of seven, learned to shoot a rifle. At age ten he went off to military school, living with another uncle, Jose Antonio Mendigutia, Batista’s Minister of Public Works, in a big house in the expensive Miramar neighborhood in Havana. In seventh grade he left to attend a boarding school in Pennsylvania. His family opposed the July 26th Movement even before Batista’s dictatorship was toppled. They moved to Miami after the revolution. Rodriguez assures his readers that they were “very much anti-communist.”

At the age of seventeen, Rodriguez joined the Anti-Communist League of the Caribbean, sponsored by Dominican Republic strongman General Raphael Trujillo, who Rodriguez refers to as a “so-called tyrant.” Thereafter, Felix trained in the Dominican Republic for an invasion of Cuba, but did not participate in the group’s failed 1959 invasion. By now living in Miami, Rodriguez went on to join the Cruzada Cubana Constitutional, one of the many anti-communist groups in the city, whose goal was to “begin military operations against Castro.” Rodriguez was made a platoon sergeant. He thought of himself as a “revolutionary,” spoke often of “honor” and “freedom,” and dreamed of “liberating Cuba.” He was eighteen years old and just graduated from high school. He was given an expensive sports car by his family and spent the summer chasing girls at the beach. He decided against going to college and instead forged his father’s name on an application to go to fight in Cuba.

In 1961, at the age of twenty-one, Rodriguez volunteered to assassinate Fidel Castro with what he described as “a beautiful German bolt-action rifle with a powerful telescopic sight, all neatly packed in a custom-made padded carrying case. There was also a box of ammo, twenty rounds.” A spot was picked out for the murder, at a location Castro was known to frequent. The young assassin tried three times to take a boat from Miami to Havana, but the boat failed to show up and finally the mission was cancelled. Rodriguez described himself as being “tremendously disappointed,” because “I was a Cuban soldier. I considered myself at war with Fidel and as far as I am concerned, he is still is a legitimate military target even today.”

Much later, Rodriguez recounted that he had learned of many CIA attempts to murder Castro. He was asked in 1987 by the independent counsel investigating the Iran/Contra scandal if he, himself, had tried to kill Castro with an exploding cigar. “No sir, I did not,” he answered. “But I did volunteer to kill that son of a bitch in 1961 with a telescopic rifle.” Rodriguez participated in the Bay of Pigs invasion of the same year, where he infiltrated Cuba with a pre-invasion group. When the operation failed, he managed to evade capture and fled to Venezuela, and then back to Miami.

After his participation in the murder of Che, Rodriguez went on to work with the CIA in Vietnam and, during the Reagan-era Contra wars, in El Salvador and Nicaragua. He boasted of his friendship with then Vice President George Bush and proudly showed people the Rolex watch he wore as a trophy, claiming that he took it from Che after he had been killed.

The United States was afraid that a large presence of U.S. soldiers in Bolivia would be counterproductive and only Villoldo and Rodriguez, disguised as Bolivian army officers, were allowed to go into the combat zones. The very top levels of the American government, army, and intelligence service actively followed the unfolding events. On June 23, Rostow sent President Johnson a summary of the situation “with guerrillas in Bolivia.” It noted that on March 24, Bolivian security forces had been ambushed, that since then six other battles had been fought, and that the “Bolivian forces have come off badly in these engagements.” Rostow’s summary referred to the cable he had sent President Johnson on June 4 where he, Rostow, reported that the guerrillas had between fifty and sixty people, but maybe as high as one hundred. He pointed out to Johnson that the seventeen-man Green Beret team had arrived and was training a new Bolivian Ranger battalion and that the CIA, because of the information given to them by Debray and Bustos, now believed Che headed the guerrilla forces. At that time six hundred Bolivian soldiers were in the counterinsurgency efforts, supported by the Bolivian Air Force. The plan of the Bolivian military was to maintain contact with the guerrillas and block their escape until the Ranger unit being trained by the Americans could move in and eliminate them.

The CIA suggests “hunter-killer” teams to Bolivian officials, and then those officials suggest them to representatives of the executive branch of the U.S. government. The United States is on both sides of the equation.

There was an urgent tone to Rostow’s assessment that without U.S aid and training the problems in Bolivia might become very serious. He pointed out that the Bolivian army was “outclassed” by the guerrillas, and if their forces were “augmented” the government of Bolivia could be threatened: “The outlook is not clear. The guerrillas were discovered early before they were able to consolidate and take the offensive. The pursuit by the government forces, while not very effective, does keep them on the run. These are two pluses. At their present strength the guerrillas do not appear to pose an immediate threat to Barrientos. If their forces were to be quickly augmented and they were able to open new fronts in the near future, as now rumored, the thin Bolivian armed forces would be hard-pressed and the fragile political situation would be threatened. The hope is that with our help Bolivian security capabilities will out-distance guerrilla capabilities and eventually clear them out.”

President Johnson told Rostow on June 23 to confer with the CIA, State Department, and Defense Department on the “whole guerrilla problem in Latin America.” The next day Rostow met with the CIA, State Department, and Defense Department. Rostow put Bolivia number one on a list of the most urgent matters because of the weak army and the fragile political situation. These factors were at the center of Che’s decision to go to Bolivia in the first place; evidently the CIA and State Department agreed with his analysis.

The United States and its Bolivian clients were moving in for the kill. Everything was in place. Rodriguez and Villoldo were on the ground providing intelligence for the Bolivian army. The head of the Bolivian Interior Ministry, Antonio Arguedas, was on the CIA’s payroll, and Edward Fox of the CIA was stationed in La Paz as a “military attaché”.

The American and Bolivian governments were also concerned about Che’s group linking up with the Bolivian workers, particularly the militant miners at the large Siglo mine. In the early morning of June 24, Bolivian Air Force planes strafed a village housing workers from the mine and their families, killing hundreds while they were still in their beds after a celebration the previous night. This preemptive action became known as the St. John’s Day Massacre. The U.S. government “was complicit in the suppression of the miners.” The U.S. supported MAPs (Military Assistance Programs) in the mining areas because they contributed to the “stability” of the military junta and its “reforms.” The embassy in La Paz “applauded the government’s response to the problem at Siglo.” Immediately after the massacre, Rostow sent a three-page report to Johnson about the incident.

On June 29 William G. Bowdler, who worked for the National Security Council, was invited to meet with the Bolivian Ambassador at his residence in Washington D.C. Bowdler described most of the conversation as a “monologue by the loquacious ambassador” about Barrientos and the political situation in Bolivia. Eventually the Bolivian ambassador got around to what was “obviously the main purpose of the invitation:” to request aid for establishing a “hunter-killer team to ferret out guerrillas.” The ambassador pointed out that the idea did not originate with him but came from friends of his in the CIA. Bowdler inquired whether the Ranger Battalion now in training in Bolivia was not sufficient. The ambassador replied that what he had in mind was “fifty to sixty young army officers, with sufficient intelligence, motivation and drive, who could be trained quickly and could be counted on to search out the guerrillas with tenacity and courage.” Bowdler told him that his “idea may have merit, but needs further careful examination.”

Apart from demonstrating how closely the U.S. and Bolivia cooperated in pursuing Che, this document shows how nefarious was the role of the CIA. The CIA suggests “hunter-killer” teams to Bolivian officials, and then those officials suggest them to representatives of the executive branch of the U.S. government. The United States is on both sides of the equation. Bolivia is essentially a messenger between the CIA and the National Security Council, which advises the President.

By the end of June, Che’s situation was getting worse. He wrote in his diary of the “Continued total lack of contact [with Joaquin’s group]; ” and that “our most urgent task is to reestablish contact with La Paz, to replenish our military and medical supplies, and to recruit fifty to one hundred men from the city.” His troops were now reduced to twenty-four people.

On July 9, after the first encounter with the guerrillas, an abandoned encampment was located, and a piece of paper found in an empty toothpaste tube listed eleven names: JOAQUIN, POLO, PEDRO, ALEJANDRO, MEDICO, TANIA, VICTOR, WALTER, BRAULO, NEGRO and GUEVARA.

In a July 5 memorandum to Rostow, Bowdler summarized the current U.S. military training role in Bolivia: “DOD is helping train and equip a new Ranger battalion. The Bolivian absorption capacity being what it is, additional military assistance would not now seem advisable. [3 lines of source text not declassified] ” On that same July 5, a high-level meeting was held at the White House. Rostow, Bowdler, and Peter Jessup (another National Security Council staffer) met in the Situation Room with representatives of the Department of State, Henderson, the ambassador to Bolivia, a Department of Defense official, and two CIA officials: Desmond FitzGerald and William Broe. The group agreed that the special strike force that had been requested by Bolivia at the suggestion of the CIA was not advisable because of the U.S. Embassy’s objections. They decided that the United States should “concentrate on the training of the Second Ranger Battalion with the preparation of an intelligence unit to be part of the battalion.”

They summarized the “U.S. efforts to support the counterinsurgency program in Bolivia against Cuban-led guerrillas,” stating that it “should follow a two step approach.” Alongside the sixteen-man military training team from the U.S. Special Forces, the United States should also provide “ammunition, radios, and communications equipment on an emergency basis under MAP and expedited delivery of four helicopters.”

Intelligence was also a concern, and here the CIA was given primary responsibility: “As the training of the Ranger Battalion progressed, weaknesses in its intelligence-collecting capability emerged. The CIA was formally given responsibility for developing a plan to provide such a capability on July 14… A team of two instructors arrived in La Paz on August 2. In addition to training the Bolivians in intelligence-collection techniques, the instructors [text not declassified] planned to accompany the Second Ranger battalion into the field. Although the team was assigned in an advisory capacity, the CIA ‘expected that they will actually help in directing operations.’ The Agency also regarded this plan ‘as a pilot program for probable duplication in other Latin American countries faced with the problem of guerrilla warfare.’” The two instructors, as we have seen, were Villoldo and Rodriguez.

A Department of Defense Intelligence Information Report dated August 11, 1967, describes “the first organized operation conducted by the Bolivian Army in the current guerrilla situation,” during the period July 8-27. The two-page report was likely transmitted by the CIA agents on the ground in Bolivia—either Rodriguez or Villoldo—but as the names of the sources, the originators, the references, and the approving author were blacked out, we do not know who prepared it. It is accompanied by a map showing the area near Nancahuazu where hundreds of the Bolivian rangers had carried out military sweeps. The operation was considered a success by the Americans accompanying them, “even though they were not successful in capturing a guerrilla unit.” One guerrilla was reportedly killed. On July 9, after the first encounter with the guerrillas, an abandoned encampment was located, and a piece of paper found in an empty toothpaste tube listed eleven names: JOAQUIN, POLO, PEDRO, ALEJANDRO, MEDICO, TANIA, VICTOR, WALTER, BRAULO, NEGRO and GUEVARA. The operation supposedly enhanced the morale of the Rangers and, “for the first time, upon being fired upon, they did not drop their weapons and run.”

At the end of July, Che reports in his diary that the “total lack of contact [with Joaquin’s group] continues.” He writes that “we have twenty-two men, with three disabled (including me), which decreases our mobility.”

In early August the Bolivian army, aided by detailed maps that Bustos had drawn for them, found the storage caves and the old base camp at Nancahuazu. Che wrote in his diary on August 14 that it was a “bad day,” and that “this was the worst blow they have delivered.” Documentation in the caves led the Bolivians to Loyola Guzmán, the key contact and financial organizer of the support network in La Paz. She attempted suicide by throwing herself from an upper story of the Ministry of Government building, but survived. Documents found in the caves were sent to CIA headquarters in Langley, Virginia, for analysis. Rostow wrote a note to Johnson about the find, telling him that the Bolivians wanted all the materials back to use as evidence in the upcoming trial against Debray.

Che listed the most important issues facing the group as a lack of “contact of any kind; no reasonable hope of establishing it in the near future.”

The Net Closes

On August 28, Joaquin, Tania, and eight others were ambushed crossing the Masicuri River and all but one were killed. Joaquin’s group was betrayed to the Bolivian Army by a farmer named Honorato Rojas. According to Jose Castillo Chavez, a Bolivian guerrilla survivor whose nom de guerre was Paco, Rojas was bribed—with an offer of money and the possibility of taking his whole family to the United States—by a CIA agent in Santa Cruz named Irving Ross. It was Rojas who told the Bolivians where the group was going to make a crossing and the army laid in wait. Che had lost one third of his troop. Barrientos attended Tania’s burial in Vallegrande a week later when her body was recovered in the river. The remaining guerrillas were now caught in a vise between two Bolivian divisions. Rostow wrote to Johnson that the “Bolivian armed forces finally scored their first victory—and it seems to have been a big one.” He told Johnson that the Second Ranger Battalion would be going into operation soon after.

On or about August 31 Felix Rodriguez, at least as he tells it, interrogated Paco, the survivor of the massacre of Joaquin’s group. Paco identified the people in Che’s band and, Rodriguez claims, provided information that allowed him to calculate Che’s exact location. Paco supposedly told him that a guerrilla named Miguel who led a vanguard was always 1,000 meters in advance of the main troop led by Che. When Miguel was killed in September, Rodriguez claims to have identified him by his fingerprints and thereby knew exactly where Che was. Although their training had yet to be completed, the Second Ranger Battalion departed immediately for the guerrilla zone, hastened by the information Rodriguez had garnered.

Che’s diary at the end of August concluded that “Without doubt this was the worst month we have had in this war. The loss of all the caves with the documents and medicines was a heavy blow, psychologically above all else. The loss of two men at the end of the month and the subsequent march on only horsemeat demoralized the troops, and sparked the first case of desertion… The lack of contact with the outside and with Joaquin, and the fact that prisoners taken from his group talked, also demoralized the troops somewhat. My illness sowed uncertainty among several others and all this was reflected in our only clash…” Che listed the most important issues facing the group as a lack of “contact of any kind; no reasonable hope of establishing it in the near future,” no ability “to recruit peasants,” and “a decline in combat morale; temporary, I hope.”

September was a month of some skirmishes, news about the loss of Tania and the others, and what Che labels “defeat” near the town of La Higuera. On September 26 Coco (Peredo), Miguel (Hernandez) and Julio (Gutierrez) were killed. Peredo, a Bolivian guerrilla leader, was one of Che’s most important men. Rodriguez urged the Bolivians to move the Ranger battalion headquarters to Vallegrande, which is near La Higuera. On September 29, again according to Rodriguez, the Bolivians were persuaded to move the Second Ranger Battalion to Vallegrande. Rodriguez joined these six hundred and fifty men who had been “so well trained” by U.S. Special Forces Major “Pappy” Shelton.

By the end of September Che reported that, after an ambush in which some of his men were killed, they were in a “perilous position.” He also wrote that “there may be truth to the various reports about fatalities in the other [Joaquin’s] group, so we must consider them wiped out… The features are the same as last month, except that now the army is demonstrating more effectiveness in action and the peasant masses are not helping us with anything and are becoming informers… The most important task is to escape and seek more favorable areas…” This was not to be.

Che’s last diary entry is for October 7. On that date, the seventeen remaining members of the troop were in a ravine near La Higuera. Che notes that “the eleven-month anniversary of our establishment as a guerrilla force passed in a bucolic mood with no complications…” The troop met an old woman named Epifania tending her goats about one league from Higueras and went to her house. They gave her and her daughters fifty pesos with “instructions to not say a word, but we have little hope she will stick to her promise.” The old woman never did betray Che, and went to the mountains with her two daughters out of fear of the army. But someone else did inform on them: A local peasant, Pedro Pena, saw the guerrillas pass his potato field, and the army was tipped off.

In his introduction to Che’s Bolivian Diary, Fidel Castro wrote of the events of the next day, October 8, 1967. “On October 7 Che wrote his last lines. The following day, at 1 p.m., in the narrow ravine where he proposed waiting until nightfall in order to break out of the encirclement, a large enemy force made contact with them. The small group of men who now made up the detachment fought heroically until dusk. From individual positions located on the bottom of the ravine, and on the cliffs above, they faced a mass of soldiers who surrounded and attacked them…”

Che was captured in the early afternoon on October 8th by Captain Gary Prado of the Bolivian Second Ranger Battalion. He had been wounded in the leg and was weaponless. His rifle had been shot out from under him. Together with his comrade Willy he was escorted to the village of La Higuera where he was held in a tiny schoolhouse.

Meanwhile, Back in Washington…

On October 9 a Department of State Telegram from American Ambassador Henderson in La Paz to the Secretary of State in Washington D.C. stated that, the previous day, Che Guevara had been wounded in the leg and taken prisoner by Bolivian Army units in Higueras. The telegram states that Che had been wounded in the leg but was alive. It calls this information reliable, presumably because it came from the CIA agents who were there. The key portion reads as follows:

“SUBJECT: CHE GUEVARA

[The document is in all capitals but is transcribed here in upper and lower

case]

1: According [BLOCKED] Che Guevara taken prisoner by Bolivian Army units in Higueras area southwest of Villagrande Sunday, October 8th.

2: Guevara reliably reported still alive with leg wound in custody of Bolivian troops in Higueras morning October 9th.”

Contradicting this document, however, is another sent to President Johnson and excerpted below, in which President Barrientos is quoted as saying that by 10 a.m. on October 9, Che was already dead. In fact, Che was not murdered until after 1 p.m. that day.

At 6:10 p.m. on October 9, Walter Rostow wrote a Memorandum to President Johnson on White House stationery that the Bolivians “got” Che Guevara, qualifying this by saying it was unconfirmed. Rostow writes that the Bolivian unit responsible for this is “The one we have been training for some time and has just entered the field of action.” The Rostow Memorandum cites information given by President Barrientos to newsmen at 10 a.m. on October 9 (although not for publication), that “Che Guevara is dead.” It further states that the “Bolivian armed forces believes Rangers have surrounded guerrilla force boxed into canyon and expect to eliminate them soon.”

The omitted sentence most likely refers to Che’s fingerprints, or even possibly his hands (cut off from his corpse in Bolivia), that were being sent to Washington to verify his identity.

On October 10 Bowdler of the National Security Council Staff sent a note to Rostow on White House stationery that there is “No firm reading on whether Che Guevara was among the casualties of the October 8th engagement.” This statement is quite remarkable, as Che had been murdered the day before, with the CIA agent Felix Rodriguez present. So the CIA certainly was aware of Guevara’s murder. However, it appears that Bowdler and the National Security Council were out of the loop, probably intentionally.

The next document, dated October 11 at 10:30 a.m. from Rostow to President Johnson, is central to the claim, including that made by Castaneda, that the United States did not want Che executed. In the document Rostow calls the killing “stupid” with its implication that the U.S. was not involved. However, on examination, the document is self-serving, and it proves nothing of the sort. In fact, its substance can be read as to the contrary. It lays out all of the reasons why the U.S. government would want Che executed and claims 99 percent certainty that this has been achieved. It then leaves a blank for something that is to arrive in Washington within a day. The omitted sentence most likely refers to Che’s fingerprints, or even possibly his hands (cut off from his corpse in Bolivia), that were being sent to Washington to verify his identity.

The Memorandum then gives a cover story that attempts to hide the U.S. role in the murder. It details what the CIA told the National Security Council concerning the murder which it claims was ordered by the head of the Bolivian Armed Forces:

“CIA tells us that the latest information is that Guevara was taken alive. After a short interrogation to establish his identity, General Ovando—Chief of the Bolivian Armed Forces—ordered him shot. I regard this as stupid, but it is understandable from Bolivian standpoint, given the problems which the sparing of French communist and Castro courier Regis Debray has caused them.”

General Ovando may or may not have ordered Che murdered, but it is unlikely he did so without instructions from, or in agreement with, U.S. officials, inasmuch as the U.S. had paid for the entire Bolivian operation; and the U.S. military and CIA personnel had trained, accompanied, and directed the “hunter-killer” groups whose job it was to “eliminate” the guerrillas. Felix Rodriguez’s story, if true, also makes it doubtful that the U.S wanted Che kept alive. Rodriguez, posing as a Bolivian officer, claims he was the highest military officer on the scene when the murder occurred. Would he have transmitted an order to murder Che had such an order been contrary to the wishes of his CIA employer? To ask the question is to answer it.

Moreover, why should we believe what the CIA told Rostow? It seems very likely that Rostow was misled to give [himself], the President, and the State Department plausible deniability. The execution without trial of a captured combatant of any sort, guerrilla or soldier, is a war crime. Taking responsibility for the murder of Che might also have made relationships with Latin America more difficult. Blaming the murder on Bolivia provided cover for a U.S./CIA operation. From the documents mentioned earlier there is evidence that the CIA did not always fully share information with the National Security Council. As we have seen above, the documents show that Rostow reported that Che was dead when he had not yet been murdered, a fact known to the CIA, and that Bowdler, on October 10, wrote to Rostow that there was no evidence to support a conclusion that Che was dead at a time when the CIA knew he was. Since 1948, the CIA has engaged in illegal actions that it does not reveal directly to the Executive so that the President can deny an accusation with plausibility.

There is simply no way that the United States government, including Rostow, wanted Che kept alive.

But whether or not Rostow was told the truth by the CIA is beside the point. For despite his statement indicating that he regarded it as “stupid” to murder Che, the substance of his memorandum to President Johnson is that Che’s death benefits U.S. policy. His claim that somehow Che should not have been killed is undercut, to say the least, by the benefits he sees in Che’s death. Here is the key part of the memorandum to President Johnson where Rostow outlines the importance of Che’s death:

“The death of Guevara carries these significant implications:

—It marks the passing of another of the aggressive, romantic revolutionaries like Sukarno, Nkrumah, Ben Bella—and reinforces this trend.

—In the Latin American context, it will have a strong impact in discouraging would-be guerrillas.

—It shows the soundness of our “preventive medicine” assistance to countries facing incipient insurgency—it was the Bolivian Second Ranger Battalion, trained by our Green Berets from June-September of this year that cornered him and got him.

We have put these points across to several newsmen.”

As Rostow points out, Che’s death can now be added to the list of deaths of other “romantic revolutionaries,” and it will discourage other guerrillas. In other words, while there would have been some benefits to U.S. counterinsurgency policy just from Che’s capture, these were much stronger as a result of his death. There is simply no way that the United States government, including Rostow, wanted Che kept alive. It was against what they perceived as their best interests. They thought his death was a major blow to revolutionary movements and wanted the press to know it.

In a very short note to President Johnson, dated October 13 at 4 p.m. and written on White House stationery, Rostow writes: “This removes any doubt that ‘Che’ Guevara is dead.”

A day after Rostow summarized the positives of Che’s death for the United States government and Latin America, the director of Intelligence and Research at the State Department wrote a six-page report entitled “Guevara’s Death—the Meaning for Latin America.” The report dated October 12, 1967, went to Rostow and the National Security Council. It emphasized, in even stronger terms than had Rostow, the positive importance of Che’s death:

“Che” Guevara’s death was a crippling—perhaps fatal—blow to the Bolivian guerrilla movement and may prove a serious setback for Fidel Castro’s hopes to foment violent revolution in ‘all or almost all’ Latin American countries. Those Communists and others who might have been prepared to initiate Cuban-style guerrilla warfare will be discouraged, at least for a time, by the defeat of the foremost tactician of the Cuban revolutionary strategy at the hands of one of the weakest armies in the hemisphere.”

It continues by measuring the effects of Che’s death in Bolivia: “Effects in Bolivia: Guevara’s death is a feather in the cap of Bolivian President Rene Barrientos. It may signal the end of the guerrilla movement as a threat to stability.”

And then in Latin America:

“Probable Latin American reaction to Guevara’s death. News of Guevara’s death will relieve most non-leftist Latin Americans who feared that sooner or later he might foment insurgencies in their countries.”

And finally, it assents that the death will strengthen the peaceful line of the Latin American communist parties affiliated with Moscow:

“If the Bolivian guerrilla movement is soon eliminated as a serious subversive threat, the death of Guevara will have even more important repercussions among Latin American communists. The dominant peaceful line groups, who were either in total disagreement with Castro or paid only lip service to the guerrilla struggle, will be able to argue with more authority against the Castro-Guevara-Debray thesis. They can point out that even a movement led by the foremost revolutionary tactician, in a country which apparently provided conditions suitable for revolution, had failed.”

In a very short note to President Johnson, dated October 13 at 4 p.m. and written on White House stationery, Rostow writes: “This removes any doubt that ‘Che’ Guevara is dead.” The “this” referred to is blanked out of the note, but as is clear from other documents, the fingerprints from Che’s cut-off hands have been matched with prior copies of Che’s fingerprints.

From Who Killed Che? How the CIA Got Away with Murder, first edition published by OR Books 2011. © 2011 Michael Ratner and Michael Steven Smith.