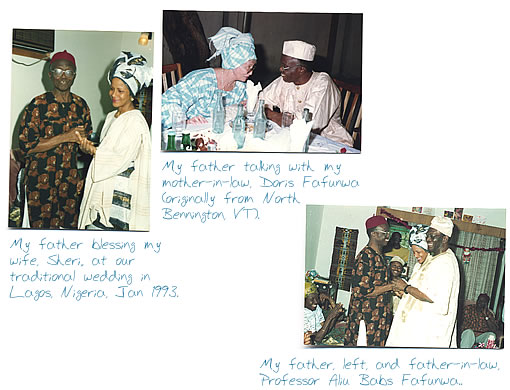

During a visit to my native Nigeria in January 1993, I saw signs that some dreadful illness had crept into my father. His spare body had filled out in a way that did not seem to spell well-being. His face had become rounder, paler, a little sadder. When he hugged me, I missed the sinewy strength that, in the past, his arms easily commanded. His gait, once brisk, had slowed to the cautious pace of somebody plagued by aches. His clear ringing voice was gone; there was, instead, a slightly enfeebled pattern to his speech, as if his body was no longer able to support the generousness of his spirits.

In June, I received news that he had been diagnosed with renal disease. Thus began my version of a son’s worst nightmare. The most graceful man I knew was beginning his final somber dance. In my adolescent days, I had often looked upon my father, first as stronger than everybody else’s father; then as simply immortal.

Christopher Chidebe Ndibe was a genial man of noble bearing, and quietly brave. His own father’s fame lay in two simple facts. In his day, he had been an invincible traditional wrestler, one of the best in his village, Amawbia. The story is still told there of his wrestling exploits, especially a comical incident during one communal festival. Cowed by my grandfather’s wrestling prowess, his opponent had lost his nerve and pleaded, “May we wrestle tomorrow instead?” To which my grandfather responded, “What then shall we do about today?” Till my father’s death, villagers saluted him with the statement, “May it be tomorrow,” a paraphrase of those plaintive words spoken by his father’s opponent.

My grandfather’s other claim to fame had to do with white men. When the first white men appeared in Amawbia, my grandfather had been one of the few men to go away with them, drawn by the economic possibilities promised by the nascent world, complete with a new cash nexus. He had hired himself out to the Europeans as a hewer of timber around the delta of Warri, in Nigeria’s midwest region, some 200 miles from his village. In those days, modern highways were nonexistent and travelers trekked long distances. When, several years later, my grandfather had not returned, his relatives, presuming him dead, performed his funeral.

Soon after, my grandfather reappeared in the village. His relatives, though much relieved, were bound by tradition not to touch him or welcome him back into the community of the living until the funeral rites were reversed. Until that was done, he remained for the villagers a dead man, a spirit.

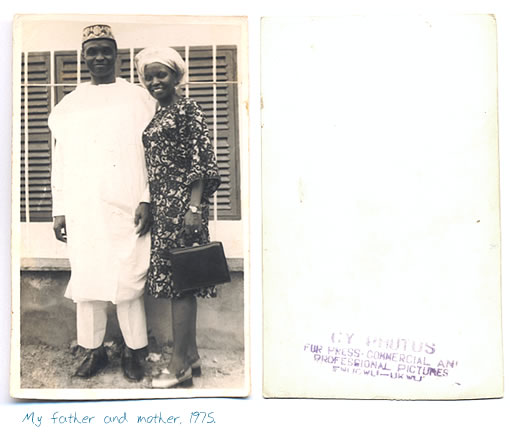

My father married my mother in 1958, when she was 33 and he was 36. At the time, any woman past 20 was considered an unviable spouse, dangerously close to a museum piece. In fact, many of his relatives had opposed the marriage, certain that age must have weakened my mother’s womb, rendering her incapable of bearing children. He had countered their plaint with the simple point that this was the woman he loved. To his scandalized relatives, this was not a simple matter; theirs was, after all, a world in which the romantic notion of love was hardly a ranking consideration in taking a wife. Having children was by far more important.

Poor for most of his life, my father nevertheless carried himself with an assured nobility. He labored at his postmaster’s job with the cheery spirit of one determined that dignity would never be foreign to him. He never raised his voice against his fellows, never became surly, never bore his circumstance, however hard and trying, on his face.

The news of his ailment stabbed me with sharp anxiety attacks. A large part of it owed to the fact that I resided in the United States, separated from my father by 7,000 miles. Besides, I was aware that his illness amounted to a death sentence, slowly, painfully, executed; Nigerian hospitals, like much else in that oil-producing country that has been misruled by a succession of military dictators, are little more than ghastly caricatures of medical care. Dialysis machines are unavailable in most hospitals. The few that have the equipment are flooded by rows upon rows of patients lying in shattering anguish, hoping their turn might come faster than death.

The greater source of my anxiety lay in realizing how much I didn’t know about my father. I knew little about his life before he became my father, before he and my mother married and had five children, four sons and one daughter, myself as the second child. My parents, of course, had told us, their children, many stories: about their own childhood, about their parents, and about that distant time of their own youth, full of excitement and peril. I had simply not paid much attention.

The reason was simple: the stories were often told in the context of rebuking shameful conduct. I was the rebellious child in the family, drawn early to smoking, hankering after all-night parties, committed to truancy, and, worst of all (in the opinion of my parents), driven to sex.

Callow and self-absorbed, I felt affronted, diminished by my parents’ stories. I quickly learned a way to distract myself during those storytelling sessions. I would focus on some cheeky fantasy, daydreaming about some girl with whom I was infatuated, or thinking about the day when I would be grown and wealthy, able to live my dream life of prurient liberty. The particular fantasy changed, but never the objective – to block out the lessons contained in the personal histories my parents shared.

I did an effective job of it. As I tried to grapple with the news of my father’s illness, I was struck by the paltriness of the memories I had of him. It suddenly dawned on me how sorely I missed the treasure of stories I had once spurned.

Visiting Nigeria in 1994 – a more or less annual ritual for me – I made sure I spent long hours with my father, asking him questions. There was so much ground we could never hope to cover, but that hardly blunted my joy that, in the race against time, I had reduced my margin of loss, however fractionally.

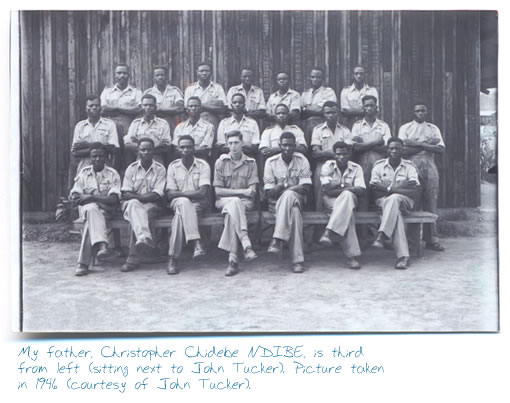

The first blurry persona I asked about was the Reverend John Tucker, an Englishman who had been my father’s regular correspondent for as long as I could remember. For many years, Tucker had been an alluringly misty figure. All I knew was that he wrote to my father once or twice each year, but unfailingly at Christmas. As a child, when my parents were away, I would pilfer his letter and run off to a quiet spot to read it. Many of Tucker’s letters were mundane affairs: a quick statement about his pastoral work, a report of the progress in school of his three children, something about his wife’s job, an expression of delight at the news from my father that his own wife and children were also doing quite nicely. There was nothing in the letters that could lift the cloak of mystery that surrounded the Englishman in my mind. Nothing explained who he was and why he and my father had become friends. There was little in the letters to reward the punishment I surely would have received had my parents found out I was peeking in their mail.

In a way, the absence of clues suited me quite well in those youthful days. It enabled me to invent a place for Tucker in what I saw as my impoverished life. My parents were lower middle class, and I wanted for symbols to bolster my social standing among my high school friends, some of whom spent summer vacations with their parents in England. I made my father’s English friend serve as my own claim to status; he became my peculiar fashion of visiting England, a country linked in my juvenile mind with idyllic beauty. If my father had an English friend, I reasoned, then what edge could my friends from wealthier homes possibly have over me?

In time I outgrew this quaint fantasy, but not my curiosity about where or how my father’s story with Reverend Tucker had begun. They had met in Burma, my father told me, a few months after World War II ended. Tucker, a lieutenant in the British Army, had been detailed as the officer in charge of the Signals platoon where my father had served for a good part of the war. My father was a non-commissioned officer with the rank of lance corporal.

My father was not one to rhapsodize war, but he took unmistakable pride in the four medals he had earned. Among the few items of memorabilia that survived Nigeria’s political crisis – a crisis that culminated in the Biafran civil war of 1967-70 – is one of those medals, as well as his discharge certificate, dated Dec. 31, 1946, from the Royal West African Frontier Force. The document notes “one small scar on the belly” as my father’s only wartime injury. Its final testimonial captured the essence of the man who would become, years later, my father. “Honest, sober and trustworthy. Used to handling men. Works efficiently without supervision. Gives great support to his superiors,” wrote his officers in the discharge certificate.

Educated only up to elementary school level, my father was able to acquire from the war the necessary skills for his postwar employment with Nigeria’s Posts and Telegraphs Department.

I remember the day when, visited by two Nigerian veterans of the war, my father brought out his lone surviving medal from the box where it was kept, like a rare totem. Though too young to make much sense of what was said, I was impressed by the passion with which they shared their experiences, how they recounted their gallantry in such and such a campaign, recalling the number of enemy forces they had, in their own words, “wiped out.”

I was always proud that my father took part in World War II, the most meaningful conflict of the modern era. I found myself awed by the war’s moral dimensions, the strange configurations of alliances it engendered, its geopolitical consequences, the sheer scale of its prosecution, and its gargantuan cost in lives. It was not until I became a serious student of African history – especially the history of Africans’ struggle to reclaim their autonomy from several centuries of European derogation and control – that I began to see the war in an entirely broader light. I was shocked – almost incredulous – when I learned that some 100,000 Nigerians had fought in the war. Other African countries, most of them under the colonial tutelage of Britain or France, also sent several hundreds of thousands of combatants.

Why was this fact glossed over in the major books on the war that I read? Why were Africans consigned to the margins, sometimes altogether erased, when the drama of this war was narrated?

Discussing the war with my father, I came close to grasping a sense of how the African combatants felt as they fought a war that was, in an important respect, the logical culmination of a species of racism with which Europe had yoked Africa. In Burma, my father was a budding nationalist. “I was constantly disgusted at the way European officers treated African soldiers,” he said. Tucker was not as haughty as some, but could not help carrying himself, much to my father’s detestation, with that very British of airs, a mixture of detachment and purse-lipped confidence, the carriage of a man secure in his place in the world, affecting an easy swagger.

Silently, my father seethed. He considered himself far more adept than his superior officer at using the signalling equipment. Tucker and the other British officers, by their presence and attitude, reminded my father of his wretched place, as an African, in the world. They reminded him that, though fighting side by side with Europeans (and for the same cause), he was a conquered man, subject to the whim of his British conquerors, his life less prized. He was a man whose world had been turned upside down by the English.

Deep down, however, my father saw himself differently; he saw himself as better than some of his British subjugators where it counted. The thinker of such thoughts is a dangerous man. My father was constantly on the verge of explosion. “One day, I angrily told Tucker that he had his rank because he was British, not because he knew signalling as well as some of the African soldiers,” said my father.

Their friendship was at once beautiful and, yes, subversive.

My father’s brusque manner alarmed his African compatriots. “Many of them dropped their jaws in shock,” recalled my father. “They were sure I would be court-martialed for insubordination. Some of them even feared I would be shot.” But my father remained indifferent to whatever fate awaited him. As it turned out, Tucker chose not to pursue the incident. Instead, recognizing that his less-than-respectful subordinate burned with nationalist ideas, Tucker went out of his way to befriend him. The two began to hold long discussions, often touching on the likely developments in British colonial possessions.

Tucker assured my father that Nigeria, like other British colonies in Africa, would regain political autonomy soon after the war. It was a view other officers mocked, convinced as they were that Africans were little more than bumbling children who would profit by submitting to many more years of stern guidance by their European masters. Tucker’s generosity began to make a good impression on my father. He began to reassess the Englishman. As he did, his mistrust of all people British soon thawed where Tucker was concerned.

The two men, defying the gulf of history that separated them, began to build a new relationship that – even in the uncertain time and turf of war-worn Burma – could be called friendship. The British officer and the African soldier, in deciding to meet on an even ground, were saying, in effect, that the arrangements of history were subordinate to the call of friendship. Their friendship was, therefore, at once beautiful and, yes, subversive.

As my father spoke, I could see that his fiery outburst against Tucker had drawn on an uncommon depth of courage from within him, to say nothing of his disregard for the imperative of personal safety. The world of 1946 was one in which my father’s kind were meant to be seen, not heard. Not heard, at any rate, speaking in irreverent terms to any British citizen, much less an officer. For in 1946, Britain owned Nigeria, and Tucker was – military ranks aside – literally my father’s master. Improbable as my father’s conduct was – in a sense, because of it – the two men would go ahead to become lifelong friends.

Back from Nigeria in the spring of 1994, I kept thinking about the meaning of my father’s friendship with the Englishman. Still excited from listening to my father recreate his Burmese encounter with Tucker, I decided to arrange a telephone conversation between the two friends. I called my father in Nigeria and linked him up, in a conference call, with Tucker in England. It was the first time they would have heard each other’s voice in nearly fifty years. I had pictured them exploding in uproarious excitement, perhaps too choked with joy to find words. How wrong I was. The two friends spoke with an unbelievable emotional restraint, their voices controlled. Their calmness at first struck me as odd, as if somehow they had betrayed their own sense of friendship.

Yet, as I thought about it later, their reserve began to serve as illustration of the character of both men, perhaps even a definition of the spirit of their times. I decided that there was a lot to admire in these men who, despite the seduction of the telephone, simply preferred to stay in touch through the rigorous habit of writing letters. I felt mildly rebuked by their equanimity, as though I had rudely disrupted the familiar rhythm of their routine. A few days after the telephone link-up, Tucker wrote my father a letter that made it clear that my trouble was not wasted. “May I say,” he wrote, “how delighted I was to receive the telephone call from Anthony [my English name; I now use Okey] some weeks ago and was amazed to be able to speak to you, as well. I would never have imagined it was possible. Will you please thank Anthony for his forethought and kindness. For days after the phone call, I was filled with pleasure to be able to speak to you after an interval of 48 years.” He underlined “delighted,” as if, now safe within the letter, he could finally express his excitement.

On May 28, 1995, I inexplicably took the handset phone into the bathroom. It rang as warm darts of water pelted my lathered body in the shower. The voice on the other side was my elder brother’s, far away in Nigeria. “Okey,” he said, “you have to be strong.” He paused and I held my breath. Then he quietly unburdened himself: “Our father died this afternoon.” Confusedly, I thought as much about the news as I did about my idiosyncratic experiences in bathrooms. Why did I find bathrooms conducive to contemplation? In them, my thoughts seem to become clearer, my imagination more vivid. Why, I wondered, did the meaning of things come to me in the bathroom, my body bared, vulnerable?

After my brother hung up, I felt a taut heaviness settle in my heart. I desperately clung to images of my father alive. I recaptured him emoting during an international soccer game (an avid lover of the game, it was one of the few occasions when his voice would be raised, in exultation or exasperation, depending on whether the team he favored was winning); washing his own clothes (a man of almost compulsive cleanliness, he never believed that his children could get his clothes clean enough); working on his farm under the sweltering sun, sweat running down his arched back as he scooped up soil with his hoe; kneeling, every blessed day, first thing in the morning and last thing at night, to lead his family in prayer. I remembered how he would always wake up at 5 a.m. to take, with my mother, a cold bath, however chilly the temperature; to say morning prayers; then to attend morning Mass. I remembered how he would cuddle his transistor radio each morning, straining to hear the world news broadcast of the British Broadcasting Corporation, many of the words strangled by static.

I recalled these familiar moments because I was too afraid to picture my father still, inert, dead. It fell to me to call Tucker in England with news of my father’s passing. He wasn’t home, so I left the message with his wife. I was relieved that I didn’t have to hear his reaction. In the days that followed, I spent much time thinking about my father’s friendship with his former English officer. What it meant to them, and what it could mean for me. On a purely practical level, how had they managed to keep up regular correspondence for close to fifty years? Even though I have friends scattered all over the world, I write to them, at best, in fits and starts. Often, when I consider writing some friend, I end up reaching for the phone and ringing them up. Was mine, then, a lazier age? A too-busy age? Or was it simply that technology has rendered obsolete the necessity for letter writing?

The hunger to probe my father’s past was linked to my desire to deepen self-knowledge, to understand the clay from which I was molded. I felt certain that there were things his friendship with Tucker could tell me about my father and his age, and about myself and mine. At the very least, it would illuminate for me a world whose terrors and triumphs I knew only dimly, through accounts in history books. It would instruct me on a world in which the most horrendous war in human history was fought by brave men, but also by the vile. The near half-century of their correspondence encompassed some of the most dramatic events between Africa and Europe.

What kind of statements did my father make as those events unfolded? Were his letters silent on sensitive political issues, say, on Nigeria’s post-war struggle for independence from Britain? For such silence would be telling, even if my father regarded it as a fair price to pay in order not to fray the bond of friendship.

My own direct experience of war began in 1967, when I was barely seven, and my country was embroiled in a fratricidal war that lasted until 1970. Despite my age, the war’s images of famine, destitution and death remain sharp in my mind. I vividly remember the throngs of emaciated refugees waiting in long, unmoving lines for relief food donated by Caritas or some other humanitarian group. I remember how many people would slump from exhaustion before they were able to fetch food. I remember women suckling their babies on sapped breasts; children whose bodies seemed sheared to the bone, their heads big and bare, their eyes sunken. It is a picture that is today all too familiar, brought into living rooms in all the colorful accents of television from Bosnia, Sierra Leone, Liberia, Rwanda, Burundi and Zaire: images of humans at their most grotesque, as if death, in making slow haste, was withholding from them the joys of a grave.

The history of Nigeria, a country with the largest population of black people in the world, is a testimony to the disastrous aftermath of Europe’s bold, but wrong-minded, attempt to create modern nation-states in Africa. Britain, France, Belgium, Portugal and Spain, in carving up Africa among themselves in the second part of the nineteenth century, paid little attention to the infusion of national consciousness in the new-fangled countries. There was no effort to redraw the map of Africa along lines that could sustain a sense of community among the subjects of these new nations, much less serve to strengthen national identity. For Europe, the overriding objective was to secure exclusive territories on the African continent for the promotion of the economic interests of individual European nations.

Nigeria exemplifies the tragic result of this cavalier, arbitrary and profit-driven policy. The British threw together more than 250 different ethnic groups and gave the behemoth a new name: Nigeria. The chaos inherent in this cartographic arrangement is best understood by imagining the forced amalgamation of all of Europe into one nation. From the very moment of its conception as a nation, Nigeria contained the seeds of fission. A volatile ethnic tension was exacerbated by religious and other cultural differences. These divisive tendencies attained a dramatic force in 1967 when the country’s southeastern region, predominantly Igbo and Christian, renamed itself “Biafra” and declared its intent to secede from the Nigerian nation. Had the secession succeeded, Biafra would have become the first modern nation in Africa created by Africans themselves. Instead, other Nigerians, defending the integrity of a territorial entity wrought by imperial Britain, waged a costly thirty-month war that squelched the Biafran dream. Britain, much to my father’s disgust, lent its considerable diplomatic and material muscle to Nigeria, thus guaranteeing the abortion of the Biafran aspiration.

My father found another reason to hold his friend’s country in contempt. Although a staunch supporter of Biafra, my father was committed to a vision of social justice, humane ideals he saw as superior to the consensus of national identity, even in a war. He became active among a group of Biafran workers and citizens who condemned the excesses of the secessionist territory’s leadership. They had written and circulated a petition rebuking the Biafran hierarchy for diverting relief donations. He paid a steep price for his idealism. My most poignant memory of the Nigerian war was my father’s unexplained absence from home for several weeks. One day, some somber-looking plain-clothed men had come and searched around our home. Then, leaving, they took my father away with them. I still remember the day he returned, sporting an unaccustomed beard that both fascinated and frightened me. For many years, I had doubted the authenticity of this memory, persuading myself that it was a nightmarish dream whose truth I had come to believe. It was only recently that my mother informed me that it was not a figment of my imagination. My father had indeed been detained, accused of mobilizing workers against the secessionist territory’s leadership.

With some luck, I hoped, there might be a letter or two my father wrote to his English friend during the war. Through the letters I would be able to feel the pulse of my father’s reaction as the war progressed and more people perished.

I arrived in England on June 10, 1997, two years after my father’s death. It was my very first visit to that old country, the object of agonized longing in my childhood years. Tucker and his wife, Lesley, had kindly offered to host me in their home for a day or two. During my stay, Tucker would explore my questions, reminisce and pore over letters.

At Heathrow Airport, while I went through Customs and Immigration, I noticed I had broken out in sweat. I was trembling with anxiety and exhilaration. My uneasiness worsened as I waited at the cavernous Paddington station for the train that would take me to Taunton, where Reverend Tucker would meet me. Then, as the train snaked out of the city, I was charmed by the English countryside. I took in the wide carpets of manicured green that rolled away on either side of the train as far as the eye could see. The train’s motion somehow gave the illusion of movement to the lush expanses of grass, transforming them into quietly flowing green rivers. Hillocks dotted the landscape here and there. After a while, the greenery would give way to clusters of brownstone houses, television antennae sticking like spikes from their roofs.

Two hours later, (but to my mind all too soon), the train drew into Taunton station, in Somerset county, in the southwest of England. I alighted from the train, certain that Tucker would immediately recognize me, being the only black passenger descending at the station. I was pretty confident that I would recognize him, too; for, though retired in 1989 from his pastoral post, he had told me he would be wearing his prelate’s collar. He walked towards me, beaming, his movement spright, his physique athletic, a soldier’s body. We shook hands, then he turned and led the way, talking as he walked, nimbly. Even then, moments after we met, there was much in his demeanor that reminded me of my father’s briskness.

In the car, the thing he asked was: how old was my father when he died? He explained that the question of age was never asked of Nigerian soldiers in Burma because some of them did not know the year of their birth. Seventy-three, I told him. “Oh,” he said, noting that that was his own present age.

Tucker’s wife, Lesley, is a biologist and retired teacher, a lanky woman with sunny eyes and a ready smile. She is passionate about birds and other wildife. I soon found out that I was not the only African visitor to their home: a pair of fly-catchers, migratory birds from southern Africa, had arrived ahead of me in May. “They come 6,000 miles,” said Mrs. Tucker of the birds nesting in the front eaves of their home. “They come all that way,” she stressed, smiling, “so I think they deserve to be treated with respect.”

The first day I asked few questions, content to listen to Tucker’s free-floating reminiscences. He recalled how, in 1946, he had passed up the opportunity to return to England in time for Christmas, choosing instead to travel through northern Nigeria as the officer accompanying demobilized soldiers to their home areas. He talked feelingly about a Hausa leather bag my father sent them as a wedding present in 1965. His wife went and fetched the bag so I could see it. He recalled my father’s proficiency as a Morse radio signaller in Burma, his mastery of sophisticated American-made equipment that other signallers found challenging. “Whenever the American soldiers were not around, Christopher was usually asked to be the relief operator,” he said. “I must have sent one or two of the signals myself, but I was nowhere near as good as your father.”

We shared family anecdotes. I told my hosts how, when we were young, my parents had made for my elder brother clothes that were too big for him. The idea was that he would wear the clothes for several years, then, once he outgrew them, bequeath them to me. The Tuckers laughed, then revealed that they, too, did the same thing with their two sons, James and Phillip. I retired to bed that night feeling a warmth inside. The Tuckers and I had been able to put one another at ease. Even so, I turned and tossed, unable to sleep. It was as if I wished to dwell on the beauties of the day that just passed. Awake, I began to realize how natural it was that this Englishman and my father became friends, and yet how improbable. Theirs was a friendship that breached several barriers. The most obvious was the ironclad sense of hierarchy in the Army, perhaps the most hierarchical institution invented by man. There was also the taboo of race, embodying all the historical distrust between white and black. There was the line of religious affiliation; Tucker an Anglican prelate, my father a devout Catholic. Then there was the salient fact that, in the 1940s, Tucker’s country held my father’s in colonial subjugation. Were Tucker to visit Nigeria in those heated postwar years, there were many clubs in which my father would not have been allowed to drink with the Englishman.

What would my father have thought about this? I was impressed by the vast difference in social background between the two friends. My grandfather had been a wrestler; Tucker’s father had been an assistant keeper of printed paper at the venerable British Museum, a polyglot who became the chancellor’s gold medallist in Latin and Greek, prose and verse. As Tucker spoke about his early life, I realized that, like my father, he had known grim privations. His voice quavered as he recalled the time when his father sold his chancellor’s gold medals in order to see the family through a difficult patch. “It’s rather a pity,” said Tucker, noting that his father had treasured the medals. “I wish he hadn’t.”

Unlike my father, Tucker never saw action during the war. And just as well, he said. The Nazi attack on Europe had started just before he went in for officer training. Then, after his training, and “thinking I was going to start fighting the Japanese any moment, the bomb was dropped at Hiroshima and the Second World War finished,” he said. “And thank God for that – that apart from training people and being trained, I had not fired a shot in anger.” After his time in Burma and Nigeria, Tucker went on to Magdalene College at Cambridge University, and then on to seminary. Ironically, Tucker’s path to priesthood was paved by his African troops. “Whilst at Prome in Burma, one day, sitting in the Signals office, talking to some of the Africans there, our conversation turned to the Christian religion,” he said. “Those around me were all Christians and English was their main language. These men had discovered that I was fairly keen on my religion. This interested them because so many of the European officers and British NCOs showed little or no interest in such matters. So they asked me: ‘How is it that so many Europeans show no interest in religion?'”

“When I was in Nigeria taking Northern troops back home, I never would have dreamt that Christopher’s son would one day be visiting me and my wife in Taunton.”

The experience opened his eyes, he said, in a startling way. How was he to explain to these Africans the incongruous phenomenon that Europeans, whose forebearers had proselytized Africans, were themselves nonchalant about Christianity? Brooding on the question, he had heard “what I can only describe as a voice saying to me loudly, ‘You have got to do something about it.’ No one else present heard anything, I am sure, but the experience, which was quite unexpected, took my breath away.” He had started on his journey to the Anglican ministry.

Throughout my first night, I processed this strange intersection of biographies and histories, Tucker’s and my father’s. The more I juxtaposed their lives, the more aware I became of the quiet drama of their story, the splendidness of their friendship, and my debt to their example. In the morning, I came out of the guest bedroom in cheerful spirits, even though I had slept nary a wink. At breakfast, Tucker surprised me with the information that he and I would drive to Lyme Regis, a coastal tourist resort on the English Channel, for a picnic. As we set out in his car through cramped village roads, he seemed to read my mind. “When I returned from the war,” he said, “I found England so small especially in comparison to the wide expanses of India, Nigeria and Burma.” We drove on for a while in silence. Then, slightly turning to me, smiling, he said, “When I was in Nigeria taking Northern troops back home, I never would have dreamt that Christopher’s son would one day be visiting me and my wife in Taunton.”

While he showed me around the resort’s museums, used bookstores and shops that retailed fossils mined from the area, I permitted myself the fleeting fantasy that I was my father and Tucker was an unlikely friend I had met in Burma. I suspected that, had fate not interfered in the matter, the Englishman would have loved to be doing the rounds with my father. We later sat down among a bank of washed stones and other sea debris to eat sandwiches and to talk, touching on as many subjects as we could squeeze into the time we had.

That evening, back home, Tucker and I sipped tea while he answered my questions on tape. He had no recollection of the confrontation my father had told me about. Instead, he remembered my father as “very cooperative and very courteous and very nice in his manner of speaking, and a very intelligent person.” He recalled the pain of the moment when he parted from my father and other demobilized soldiers headed for the eastern part of Nigeria, because he had been assigned to travel with those going north. On arrival in Lagos, all the troops had stayed at a camp situated beside a railway line outside the city. “When the time came for my departure, it was almost a tearful farewell,” Tucker said. “I remember that, as my train slowly puffed its way out of the camp station, a number of my signallers ran full tilt alongside the track waving at me until they could no longer keep up.”

My father’s very first letter to his English friend was dated September 9, 1947. It was written against the backdrop of a sharp rise in nationalist activity in Nigeria and the stepped-up efforts of British colonial officials who ridiculed the agitation for self-rule. Part of the vibrancy of nationalist agitation arose from ideas generated by World War II. For colonial subjects, perhaps the war’s most inspiring document was the Atlantic Charter, a series of declarations issued in 1941 by America’s President Franklin Delano Roosevelt and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill. The two leaders pledged to “respect the right of all peoples to choose the form of government under which they will live.” Africans took the document as a promissory note for their own self-determination once victory was secured by the Allied forces. They therefore felt bitterly disappointed when, at the war’s end, Churchill, in an egregious act of revisionism, argued that colonial subjects were not included in the document’s idea of “peoples.”

The tone of my father’s 1947 letter showed how soured he had become with British colonial policy. “Yes,” he wrote, “we Nigerians as a whole used to be cheerful always and under all conditions with less money and amenities, but I can tell you that this is not true today. The cause for this is that we wake up daily only to see that our position, economical, social or political, is worse than yesterday. We are denied all rights which every living creature should enjoy… Laws after laws are made whereby our lands and other God-given rights to the poor natives are taken from them. These make the whole population feel disappointed in our so-called protectors, hence every one here is now unhappy and disgusted with the British attitude… the flame of nationalism burning in the minds of almost all Nigerians cannot be quenched.”

Twenty-two years later, in the midst of the civil war, my father wrote Tucker a heartrending letter. “The story of my family and my country for the past three years is a long and painful one,” he wrote. He described “the pogrom, the blockage by air, land and sea, and the war of genocide and total extermination of Biafrans engineered by Harold Wilson’s [British] government and sustained by that government up to this day.” He said the account of Britain’s complicity in the carnage “will make a sorry reading for a Christian of your type.” The letter’s only hopeful note was the remark that “my wife, our five children – four boys and one girl – and I are still breathing God’s free air even though much suffering and hunger have had their effects on us.”

When it came time to leave, I was deeply grateful to Tucker for the glimpses he had offered me of my father and of himself. What moved me even more was to see how two ordinary men had done extraordinary things, how they had salvaged something beautiful from the ravages of history; how, transcending their own narrow biographies, they enacted a friendship that could be quenched neither by distance, time, war, nor, for that matter, by death.

Following my father’s passing, Tucker and my mother agreed to take up correspondence. Mrs. Tucker’s parting words to me only deepened my gratitude. After hugging me once, twice, then a third time, she said, “You know, it feels like one of my sons leaving home.” In the silence of my heart, I thanked my father and his worthy English friend.

Okey Ndibe is the author of Arrows of Rain, teaches at Simon’s Rock College of Bard in Great Barrington, MA, and is finishing work on foreign gods, inc. Ndibe has also taught at Connecticut College in New London, CT. He was for one year on the editorial board of the Hartford Courant and, from 2001-2002, was a Fulbright professor at the University of Lagos, Nigeria.