How New York’s worst day led to its greatest photography exhibit ever.

“We are in a tension between the speed of history—which happens very, very fast—and progress, which happens very, very slowly,” Gilles Peress wrote in 1999. On the morning of September 11th, 2001, history happened fast, and the pace hasn’t let up since. But it was within this calamitous event that, I believe, Peress realized his vision of photography’s democratic possibilities. 9/11 turned out to be a defining moment in Peress’s work, though in indirect and unanticipated ways. And what it showed is that there are no aesthetic answers to the questions he has been posing about photography’s place in the world, only democratic—which is to say, political—ones.

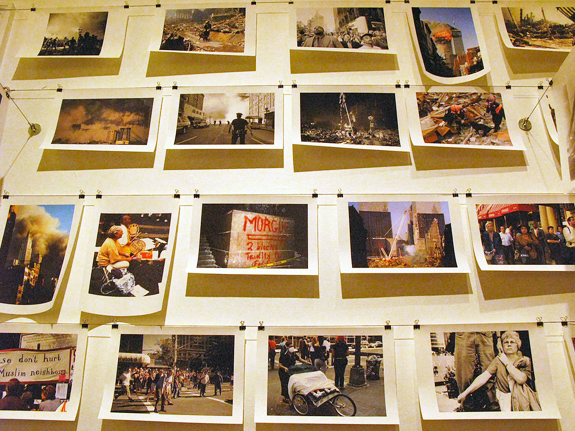

A week after the assaults, Peress and three friends—curator Alice Rose George, photography professor Charles Traub, and writer Michael Shulan—opened a storefront exhibition of photographs, called “Here is New York,” in Manhattan’s Soho neighborhood. The organizers put out an open call for photographs from “anybody and everybody”: not just professional photographers but all the amateurs—all the citizens—who had become documentarians of the city’s crisis on 9/11 and in the strange, unprecedented days that followed. More than five thousand pictures poured in to the exhibition, which displayed them without attribution (photographs by Magnum stars were mixed with those by unknowns). The organizers’ aim was to gather, and show, images that portrayed the array of experiences that we now call, in a kind of shorthand, “9/11.” This meant documenting not just the attacks themselves—captured in those still-breathtaking pictures, taken from so many locations by so many people, of the planes crashing into the towers and the subsequent conflagrations—but all that surrounded them.

It meant portraying the reactions—horrified, scared, anguished—of witnesses of that day. (As the attacks unfold, onlookers grip their heads, clutch their throats, or lay their hands over their hearts, in what must be unconscious universal gestures of fear or disbelief.) It meant documenting the ubiquitous, increasingly forlorn “missing” posters, with their poignant revelations of intimate details (“tattoo of heart in pelvic area”); the exhausted yet indefatigable rescue workers; the exodus of scores of thousands of workers across the Brooklyn Bridge. It meant showing the enormous scale of the twisted rubble, which could conjure comparisons only to war sites or sci-fi movies; the memorials, and the gatherings of strangers around them, that sprouted spontaneously as expressions of grief; the graffiti that expressed a wide range of feelings and of solutions, from universal love to war without mercy. One such photograph shows a young women who has spray-painted “PAY BACK” in thick black letters on her white undershirt; in another, someone has etched “Welcome To Hell” on the back window of an ash-covered car.

Documenting 9/11 meant, also, documenting the look of the city itself: not just as an agglomeration of buildings, bridges, sidewalks, and street signs but as a living, breathing, achingly vulnerable actor in this drama. It meant portraying the city’s residents: stunned and hurting, yet unified in ways we lifelong New Yorkers had never experienced. (Among other things, New York suddenly became a Third World town: out on the sidewalks, people huddled over shared radios and TVs.) Never before had the identities of New Yorkers as individuals fused so intimately, and so tenderly, with the place itself: the city was—we were—wounded, fearful, fearless, furious, proud. The city’s “body politic” became literal.

“Here is New York” was a refutation to years of critical cant about the exploitative, voyeuristic, alienating qualities of documentary photography. On the contrary: as Michael Shulan wrote in the exhibit’s accompanying, 864-page book, “Photography was the perfect medium to express what happened on 9/11, since it is democratic by its very nature and infinitely reproducible… To New Yorkers this wasn’t a news story: it was an unabsorbable nightmare. In order to come to grips with all of the imagery that was haunting us, it was essential, we thought, to reclaim it from the media.” Photographs made real our own experiences, and let us see those of others; photographs were the beginning of individual understandings within a collective context. I remember going to the _Here is New York_ exhibit several weeks after 9/11, and it is the sense of place more than the individual pictures that has stayed with me most. The exhibit’s atmosphere, simultaneously lively and bereft, was like no other I had ever felt in a museum or gallery. We were not just lookers, we were discoverers; and this activity of discovery was intertwined with—was dependent on—the presence of others.

September 11th was not only an unusual political event, but an unusual visual one too. There is little evidence of the dead, because most were burnt into dust: Ground Zero was a mass grave, but one without many bodies. (In this, the 9/11 terrorists accomplished something the Nazis had fervently desired but failed to achieve: the almost complete obliteration of the dead.) This is why the event lacks the usual atrocity photographs, such as mounds of corpses; there are relatively few images of bloodied or wounded people, either. One picture in Here Is New York shows a severed, bloody, shredded leg and foot lying on pavement; the image is shocking because it is so grisly, but also because it is so rare.

This means that the overwhelming number of 9/11 photographs portray onlookers; those who escaped from the collapsing buildings; and rescuers. There is one major—and hugely controversial—exception to this: photographs of those who killed themselves by jumping from the burning towers. These are, in my view, the most powerful images from the event, for they bring us closer, more than any others, to imagining the experience of the victims. They are also among the least-reproduced, least-seen images of 9/11; indeed, they are despised.

There are an unknown number of such photographs, taken by different people from different spots. Here is New York includes one, as a vertical double-spread. It shows four bodies, silhouetted in black against the sky, as they tumble through the air: an acrobatics of death. The New York Times also printed one such image, taken by Associated Press photographer Richard Drew, on September 12th (though not on the front page, and never again). These photographs, and others like them, have been published all over the world, but in this country they have been vilified, for reasons I don’t quite understand, as an insult to the dead. The images have become, as the journalist Tom Junod wrote, “at once iconic and impermissible.” Yet not until I saw Drew’s picture in the Times did I realize—a realization that hit me, almost literally, with a dread-filled thud and a mounting sense of panic—that those who were trapped in the buildings had been forced to choose between being burned alive and jumping to their deaths. Not until then did I allow myself to contemplate the last minutes, and maybe hours, of the victims; not until then did the true horror of the event, which had nothing to do with burning buildings and everything to do with burning people, begin to penetrate my numbness and shock. “The desire to face the most disturbing aspects of our most disturbing day was somehow ascribed to voyeurism,” Junod rightly observed, “as though the jumpers’ experience, instead of being central to the horror, was tangential to it, a sideshow best forgotten.” The word “taboo” is overused, but it accurately describes the status of this wrongly reviled set of photographs.

New York seemed more racially unified on 9/11 and the immediately following days than it had ever been, at least in my lifetime. For those of us who have grown up within, and are ever conscious of, the city’s racial drama—often brutal, sometimes funny, occasionally uplifting, frequently guilt-ridden, reliably hypocritical—this was a welcome relief. It was as if Art Spiegelman’s heretical New Yorker cover, in which a Hasidic man and a black woman amorously kiss, had been realized; this time, though, unity was born of violence rather than of love. Some of the photographs in Here is New York allude to this (temporarily) changed racial dynamic. In one picture, a young black couple, who have matching, almost-shaved heads and wear matching white tunics, sits on a park bench; the woman clutches a tissue and sobs, while the man’s right hand is placed protectively on her head. Next to them, a young Asian woman leans toward the woman while a white man kneels on the sidewalk in front of her; he clasps her hand as if begging her, willing her, into some kind of solace.

September 11th changed perceptions of class, at least for a while. Firemen and policemen were the new heroes, and many of Here is New York’s photographs document their backbreaking but largely futile efforts to find survivors in the rubble. In addition, the event produced a subtler, yet still distinct, change in attitudes toward the commercial life of the city, and a new appreciation for it. In Here is New York, the ubiquitous advertising and business signs that adorn the city’s storefronts, billboards, and bus stops don’t look ironic, as they have in photographs dating back to Walker Evans; nor can they be read as sardonic critiques of consumer culture, as in so many postmodern works. Here, on the contrary, every shuttered store seems like a defeat: not of capitalism, but of us. A deserted, humble coffee-and-bagel cart—an image taken, as it happens, by Peress—looks like a sleepy, dear friend who we want to awaken; a crowded, brightly lit coffee shop boasting, probably falsely, of “gourmet muffins” and “gourmet croissants” is suddenly a delight; an eerily empty West Broadway—its obnoxiously overpriced stores now closed—seems unutterably sad. After 9/11, even Marxists yearned for the city’s rough, garish world of capitalism to spring back to life.

“Here is New York” was a promiscuous exhibit (as is the resulting book). That was its strength. Spreading its arms wide, it took in as much as possible, as if its organizers understood that only by doing so could we begin to see ourselves and each other, and to confirm our experiences while simultaneously questioning them. It was a remarkable project: a conversation in images, a visual dialogue between citizens, a Whitmanesque vision constructed from sorrow. Shulan wrote that the exhibit’s organizers had hoped the photographs would be “allowed to speak for themselves, to each other, and to the viewer directly;” the show was premised on the idea “that wisdom lies… in the collective vision of us all.” As a book and, especially, an exhibit, _Here is New York_ justified the belief that this democratic ideal still lives: even, or perhaps especially, amidst catastrophic loss.

Since 9/11, Peress has photographed in Iraq, Israel, and Afghanistan (though he still does not think of himself as a war photographer). And he returned to Rwanda, where, he says, “I tried to drop every element of style, to be as simple as possible.”

Peress also turned his attention homeward, documenting what he called the “wake” of Wall Street as the financial system crashed in the summer and fall of 2008. But nothing was as difficult as the photographic journey into the economically depressed heartland that he took during the Obama-McCain presidential election. “It is far easier to be in Iraq with the Special Forces than to be in the post-industrial, post-consumer landscape of Ohio,” he said several weeks after Barack Obama’s win. “The current economic landscape of the U.S. is a far greater challenge. How do you build a language that changes our interpretation of reality? That’s a big one.”

In the weeks before the election, Peress drove through rural Ohio and made a series of videos (composed mainly of still images) that he posted on the web. In one, called “A Sleep of Reason”, Peress finds himself in Cleveland, and his sense of bafflement recalls, at least to this viewer, that trip he made three decades ago to revolutionary Iran: once again Peress is the stranger in a strange land, wandering through a landscape of confusion. But there is no energy, no fury, and certainly no revolution in Cleveland—only a bleak, spooky solitude: empty streets, empty roads, empty factories. “There’s nobody, nobody out,” Peress phones home to a friend. “It’s like the place has been nuked.” Later, he returns to the city searching for signs of life. First, he meets four African-American men who work as seafood packers: “Do anything but go to prison,” one of them explains. Then he encounters three shyly smiling young men—attired in ill-fitting black jackets, black bow ties, white shirts—employed as valet parking attendants. It turns out that two are Iraqis from Basra, the other a Serb from Sarajevo. Even in desolate, deserted Cleveland, history catches up with you.

For Peress, the new media landscape in which we all live—defined, especially, by the Internet—opens up all sorts of possibilities for photographers and viewers. He envisions the Internet as a potentially anti-authoritarian tool in what he calls our “post-postmodern” era. “We are entering into an age in which visual language is defined by a dialogue between photographers and audiences,” he says. “This means not just the democratic posting of images but the democratic interpretation of images.” The viewer is no longer the passive, grateful student, the photographer no longer the all-knowing, all-seeing teacher who chooses which decisive moments will live or die. “There is no longer a voice of authority, with univocal images created from above,” Peress argues. Goodbye, then, to “the notion of the creator of images as a Nietzschean demi-god. We need deep humility, humbleness, in relation to our formulation of reality now.”

It is that formulation—that search—that still drives Peress, be it to Tehran, Kigali, or Cleveland; like his predecessors such as Capa, Peress knows that history is made by all sorts of people in all sorts of places in all sorts of ways. But despite his experiments with video, Peress insists that the photograph is “still a space to reorganize our thoughts about reality and our place in the world. How do you disentangle the surface of reality?”

That question has recurred throughout photography’s lifespan; it has haunted, angered, and inspired generations of thinkers, going all the way back to Walter Benjamin and Bertolt Brecht and up through Susan Sontag and the postmoderns. Yet after a century of astonishing images, and a century of astonishing violence, Peress proposes no answers. Instead he poses another, more basic question, one that presses not only on documentary photographers but on journalists, filmmakers, and human-rights advocates; indeed, it challenges every inhabitant of our shared, wounded world.

“How do you make the unseen seen?” Peress asks.

Susie Linfield directs the Cultural Reporting and Criticism program at New York University. The Cruel Radiance, her book on photography and political violence, will be published November 1.

Further Reading:

Telex: Iran : In the Name of Revolution, Farewell to Bosnia, and The Silence, by Gilles Peress.

Here Is New York by Gilles Peress, Michael Shulan, Charles Traub, and Alice Rose George.

Editors Recommend:

Living with the Enemy: Applying the ideas of Holocaust survivor Jean Améry to present day Rwanda, Susie Linfield argues that reconciliation after genocide is just another form of torture.

Twin Peeks: Suzanne Menghraj explores two daring acts of seeing in and around the wilds of New York City.

To contact Guernica or Susie Linfield, please write here.

Reprinted with permission from The Cruel Radiance: Photography and Political Violence by Susie Linfield. © 2010 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved.