H

is face is almost everywhere. With a stoic gaze and a stately uniform, Field Marshal Abdul-Fattah Al-Sisi looks out from magazine covers displayed at Cairo’s corner newsstands and posters decorating gas stations in sleepy Red Sea towns. Following the military’s ouster of the Muslim Brotherhood-affiliated Mohammed Morsi last July, a nationalistic fervor has gripped Egypt, and media outlets have widely lionized the retired general. He’s been cast as the next executive, although elections won’t be held until the end of the month. But can political cartoonists draw the country’s most powerful personality with the confidence their work will be be published?

“Maybe, but it would be difficult,” says Anwar, twenty-six, head of caricature for Al-Masry Al-Youm, Egypt’s largest-circulation private newspaper. Sporting a curly mop and dark square spectacles, the international uniform of illustrators, Anwar sketches a cartoon on page three that hundreds of thousands of readers turn to every morning. Unlike state-run outlets that broadcast the official narrative of the prevailing regime, Al-Masry Al-Youm, among a string of publications founded in the 2000s, endeavors to strike an independent tone. But as Anwar explains around the corner from his office, since the summer coup he’s avoided depictions of the military strongman and jabs at the armed forces. “If the editor in chief is scared, and doesn’t like the cartoon,” he says, “it will be rejected every time. This is one of the most difficult periods that cartoonists have ever drawn.”

Wherever one stands on the military’s entrenched authority, the past year has been painful for Egypt, violence crippling journalists’ ability to document the changing landscape. Regime forces raided ten media outlets and television stations in the aftermath of Morsi’s removal, and more than sixty-five journalists have been detained since July, according to the Committee to Protect Journalists, which ranked Egypt the third-deadliest country for the press in 2013. Seventeen members of the media remain in prison, and a trio of Al Jazeera journalists is on trial on trumped-up charges related to the government’s “war on terror,” which Cairo-based independent correspondent Sharif Abdel Kouddous describes as a premise “primarily being used to re-empower the security state and silence opposition voices.”

Among these voices are Egypt’s political cartoonists, satire long a chief ombudsman for the country. While they don’t report from violent protest zones, criticizing the security state is still perilous. Illustrators capture the everyday challenges Egyptians face, and produce work that is far-reaching: legible to the illiterate and capable of transcending cultural, class-based, and generational barriers. Plus, while illustrations may be creations of the imagination, their imagery goes straight to the gut. It shows the blunders of the ruling class in a moment’s glance. Protesters in Tahrir Square carried cartoons on placards, not opposition op-eds.

Mainstream newspapers haven’t dared to mock Sisi head on in political cartoons, and as the space for dissent has shrunk, some illustrators have been forced to pick sides or pack up, like Anwar’s friend and former colleague, a 27-year-old funny man named Andeel. He produced a vast and frenetic body of work for Al-Masry Al-Youm responding to the political crises of last summer, but most of it was relegated to his personal Facebook page. Chided for speaking out against censorship, he left the publication in October, seeking more space to push back against establishment storylines.

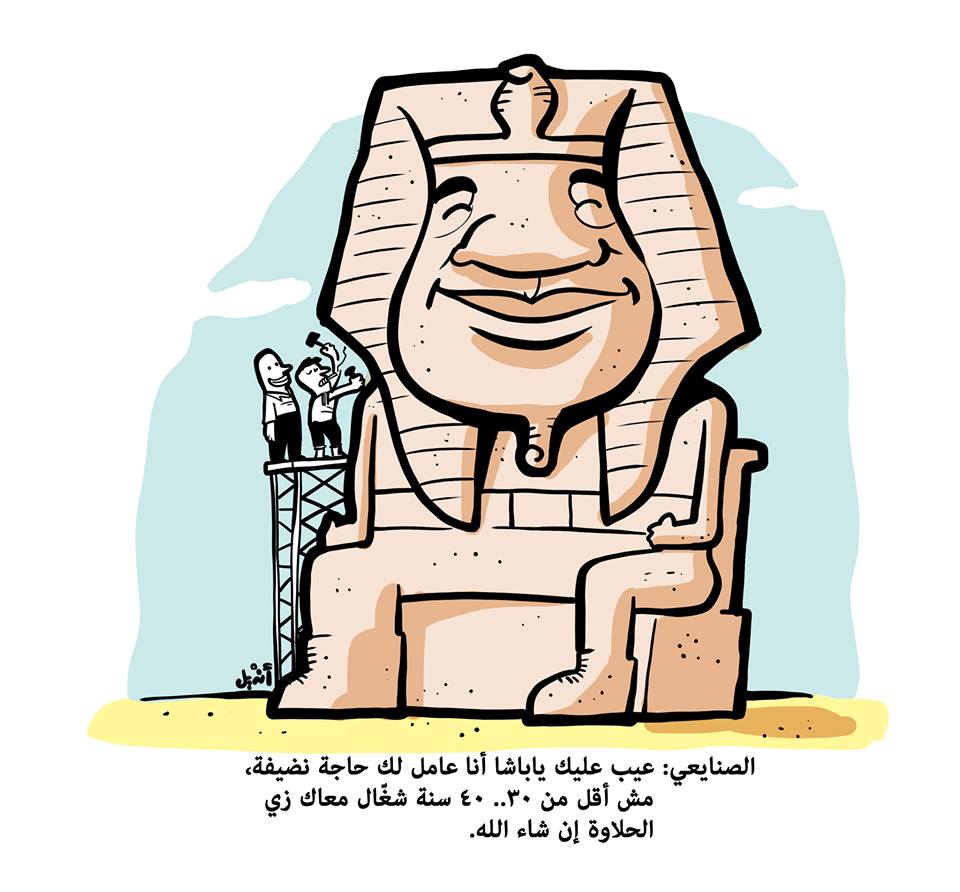

“The coolest thing for cartoonists,” Andeel argues, “is to make fun of the strongest man in the country.” Upon leaving, he shared a bold criticism of the field marshal with upwards of 37,000 Facebook fans. “I wasn’t working at any place, and I didn’t have to deal with any of that, so I just drew him,” he says. The caption below reads, “For shame, sir! I’m really doing a proper job on this one—it’ll work like a charm for thirty or forty years at least! God willing.” Hosni Mubarak, the octogenarian autocrat ousted in the 2011 uprising, had been president for thirty-one years.

Anwar may be confined by the media’s deference to the military, but he’s developed workarounds to shift the narrative, and prefers to reach a wide audience, not just Egyptian millennials. “If you were to draw Sisi as a killer,” he says, “you will get claps from Facebook. This would make you a hero, but I’m not sure it will change anybody’s opinion.” Last fall, he drew a revolutionary youth (a millennial active in the Arab Spring), a Brother (a supporter of the Muslim Brotherhood), and a man dressed in a “CC” t-shirt (a backer of Sisi) sitting together. “The Government is #$%@,” they lament in a collective speech bubble.

His placement of the three disparate groups on equal footing is subversive. Widely circulated state newspapers never publish illustrations of “normal” Brotherhood supporters, but rather paint them as pugnacious terrorists with beards. Egypt is largely represented as a single token citizen, a secular adult male—as if Islamists, rebels, and women were not truly Egyptian. In Anwar’s frame, the three political factions who have come to represent Egypt speak with one voice.

Young illustrators like Anwar and Andeel, who sharpened their pencils during the twilight of the Mubarak regime, emerged from the revolution with new slang and a penchant for taking on authority. They are agitators and outliers in Egypt’s new political climate, responding to volatility and uncertainty through satire—and cracking very different jokes.

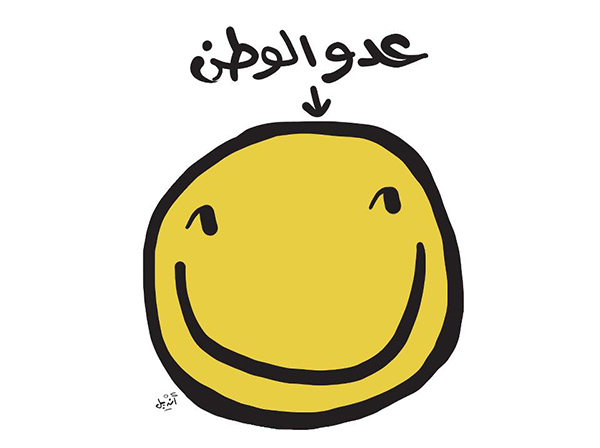

Andeel has drawn for the Egyptian press since high school, his doodles taking him from Kafr Sheikh, a small Delta town three hours north of Cairo, to the cosmopolitan capital. “I am always the youngest person in the room,” he says with a grin. When he received his first paycheck for a cartoon, about thirty dollars, he says his grandmother couldn’t believe it. But humor and creativity run in his family. Andeel’s brother is a comedian who was briefly arrested by Morsi’s general prosecutor last year for a stand-up bit on TV that allegedly insulted Islam. Andeel changed his Facebook profile picture in support, the caption reading, “Enemy of the State.”

Andeel is short but always the center of attention, either due to his unflagging energy or wardrobe of brightly colored t-shirts. He plays synthesizer in a rock band called Hot Wave, and hosts Radio Kafr Shiekh, a parody of his hometown that involves talk-show banter and football matches narrated in a country bumpkin drawl.

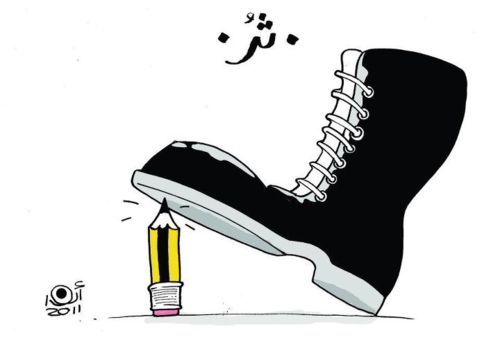

Three weeks before the Tahrir rebellion in early 2011, Andeel and Anwar, among other friends, launched an alt-comics zine called Tok Tok, “an answer to censorship,” they said, and a venue where they could draw the routine struggles of life in Cairo. By the next fall, the two illustrators were sharing an office at Al-Masry Al-Youm, drawing daily copy and battling to get radical cartoons past their editors. Eighteen months of interim military rule separated Mubarak’s resignation from the democratic election of Morsi, and oppressive practices surged. When a higher-up at the newspaper instructed Anwar and Andeel to scrub from their lexicon the popular protest chant “Down, Down with Military Rule,” they responded with illustrations for the next day’s issue. Three years later, the images still resonate: heavy boots crushing pencils that appear all too fragile.

Last July, following the first anniversary of President Morsi’s election, army leaders delivered a forty-eight-hour deadline for him to do something—anything to end the political impasse. They were responding to the people’s call, prompted by Tamarod, or “Rebel” in English, a grassroots movement that had gathered millions of signatures and planned large-scale demonstrations. Across the country, electricity outages and hours-long queues at petrol stations mounted the pressure.

Morsi’s presidency had been defined by crisis, and cartoonists weren’t shy about depicting the bumbling, pedestrian politician’s missteps. They enjoyed a relatively high level of autonomy, not because the Islamist was a liberal, but because his government was highly ineffective—crackdowns on penal code violations like “blasphemy” and “insulting the president” never made it very far and failed to deter most opposition journalists. Morsi was depicted as a cult leader and a chauffeur with no sense of direction. For Al-Masry Al-Youm, Anwar and Andeel drew the executive stained with blood, indicting both his powerlessness and his complicity in state-sponsored violence.

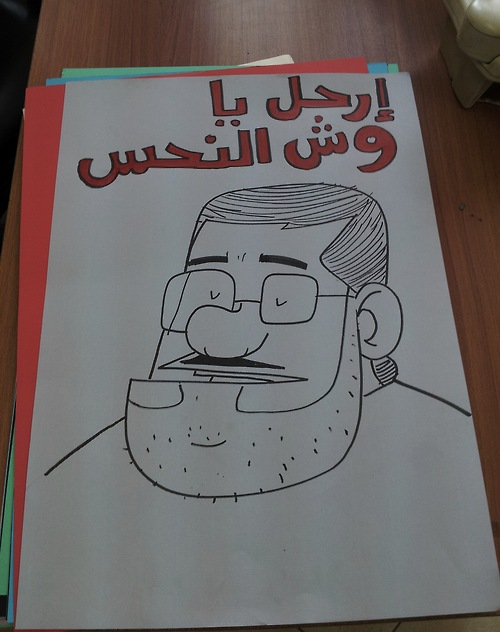

I visited the newspaper’s caricature department in the chaotic last days of Morsi’s presidency, and found it deserted. Desks were strewn with crosshatched paper, piles of books and markers, the illustrators having taken to the streets. Anwar’s hand-drawn placard from a recent demonstration pictured a chubby-cheeked man with a beard, his eyes closed. The caption read, “Get out, you face of bad luck,” implying not only that Morsi was bad news, but that Anwar was displeased with his features.

In the spirit of Egyptian tradition, the coup was late. Maybe the generals were stuck in traffic. The military’s deadline for Morsi had passed, and Anwar and Andeel sat on the couch with their friends, wondering what to order for dinner.

In the throes of a second revolution, both cartoonists supported the unseating of Morsi. “‘This is a stupid regime that is in control right now,’” Anwar remembers thinking. “‘We have no plans of what will happen after.’” Andeel believes that Morsi overstepped, ruled undemocratically, but that the military’s subsequent clampdown has been even more egregious. “We all knew this was going to happen,” he says in retrospect. “Since the very beginning of the Tamarod thing, everyone realized that the army was planning something.”

It was “cinematic,” he says, when the military seized the reigns. They carted a cast of characters onstage: the Mufti of Al-Azhar (the most prominent Islamic leader of the country), the Coptic Pope (the top Christian cleric), Nobel Laureate Mohamed Elbaradei (a secular figure and world-renowned diplomat), a young revolutionary kid in a polo shirt, and other fig leaves broadcast on TVs across the nation, meant to legitimize the junta. Special effects included fighter jets cutting hearts through the sky with their contrails. The physical presence of military vehicles in the streets and low-flying helicopters gave the theater a sense of immediacy. The hero was Sisi and the villains were the Muslim Brotherhood.

Hours later, Andeel posted a video online. In it, Anwar bangs a tambourine, leading others in a joyful, call-and-response song. “Why is Morsi crying?” “Because Sisi arrested him,” everyone replies in unison.

The military’s iconography is grounded in the body. “Bless Your Hands,” a song that recycles an old army melody, became the soundtrack for its renewed political role. While cartooning for Al-Masry Al-Youm, Andeel wrote about the anthem for Mada Masr, an online news outlet that has fiercely maintained its independent editorial line:

“Bless your hands” also implies the fulfillment of duty: that the military was asked by the people to rise up against Morsi.

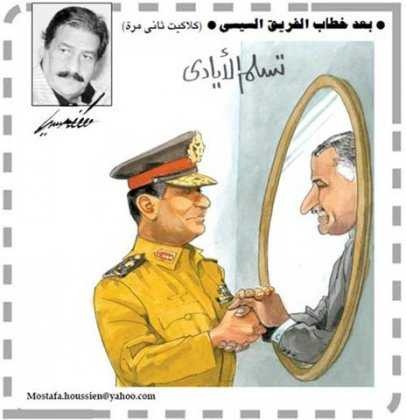

The cartoons by 77-year-old Moustafa Hussein serve as a baseline for the nationalist narrative. He’s been illustrating for the state-run daily Al-Akhbar for forty years, and over the past four years has drawn in support of four distinct governments: Mubarak, the Military Council, Morsi, and now Sisi. An August cartoon by Hussein portrays Sisi reaching into a mirror to shake the hand of his reflection, Nasser. Above the two smiling gentleman is the caption “Bless your hands.” Though mirrors tend to play tricks in literature, this one offers a legitimacy to Sisi. Nasser appears not only to be giving Sisi his blessing, but also carte blanche to steer the ship of Egypt by any means necessary.

Criticizing the regime has come to signify backing the Muslim Brotherhood, creating a zero-sum game for Andeel, who is neither a Brotherhood enthusiast nor a military cheerleader. After Morsi’s ouster, he produced his strongest work—twenty-seven cartoons that July, only a few of which Al-Masry Al-Youm consented to print. While others are now beginning to prod the military, Andeel was very much ahead of the curve. “It was just a natural reaction,” he says. “I didn’t think about it as much as I just felt.”

Submitted just days after the armed forces toppled Morsi, here is one of Al-Masry Al-Youm’s print rejects: a postcard of a nuclear family, eyes closed, grinning and waving Egyptian flags. All of them are splattered with blood.

Andeel drew it on July 11th, after authorities first attacked pro-Morsi protest camps. As caricaturists of the old guard published rosy celebrations of the military in the official press, Andeel zoomed in on the consequences of the overthrow. Al-Masry Al-Youm posted the image to its website, but declined to print it “because they don’t want people to feel bad,” says Andeel.

Following the shooting of dozens of demonstrators by police and armed civilians on July 27th, Andeel posted an image to Facebook highlighting the absurdity of widespread, blind support for the regime’s violence. A young, oversized soldier sits incongruously at a street café, his clothes and hands bloodstained. Two men at the table are jarred, but a third puts his arm around the serviceman and introduces him, “He’s with me, guys.”

Soon after, Andeel drew a young man beside a woman at a party, remarking, “So you are a fascist, too? Cool!” The pick-up line condemns unconditional loyalty to the armed forces, underlining how the youth of the revolution have come to support a new authoritarianism.

“I was working for a newspaper that was very highly distributed, reaching out to millions of people every week,” says Andeel. “I could have used that channel with its possible limitations to sneak in my opinions and my values.” Instead he drew for Facebook, where he could stick to his principles.

On August 14th, security forces claimed Brotherhood protest encampments were stockpiling weaponry, and killed a thousand demonstrators across Cairo, piling bodies in field hospitals.

Journalists covering the mayhem were trapped, and at least three died. Egyptian papers failed to adequately cover the deadly dismantling of the rallies, and Andeel’s cartoons on the topic were repeatedly turned down.

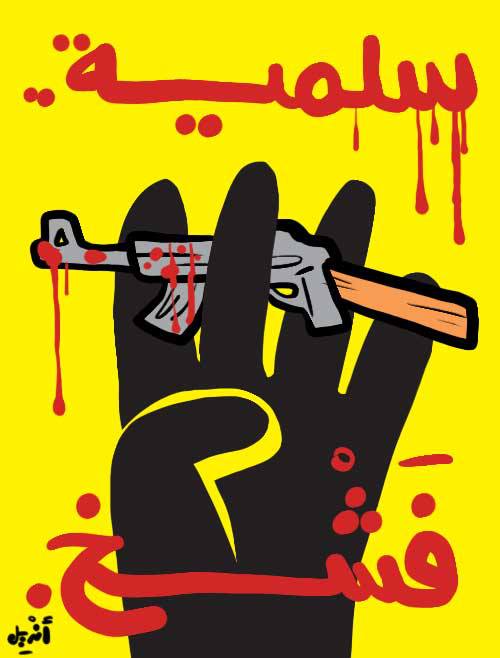

The Muslim Brotherhood created its own symbol in solidarity: the four-fingered salute, which derives from an anti-coup encampment called Rabaa El-Adawiya, where many deaths were concentrated (“rabaa” translates to “four”). The sign went viral, with yellow and black Rabaa posters in shop windows from Istanbul to Berlin, though considered contraband in Cairo. Freedom and Justice newspaper, the Muslim Brotherhood’s mouthpiece, replaced the photo of Morsi that had been published atop every page since his ouster with the Rabaa symbol, shifting away from the deposed leader’s personality as a representation of its struggle. The hand gesture was instinctual, simple, and both pro-military and Islamist cartoonists began to employ it as shorthand, a way to generalize the large and diverse movement deeply woven into Egypt’s political fabric.

Andeel used the Rabaa salute, holding a rifle, to suggest that the Muslim Brotherhood protest encampments were armed and dangerous, rather than peaceful and innocent. But at the same time, he was also harshly indicting the military for using brute force.

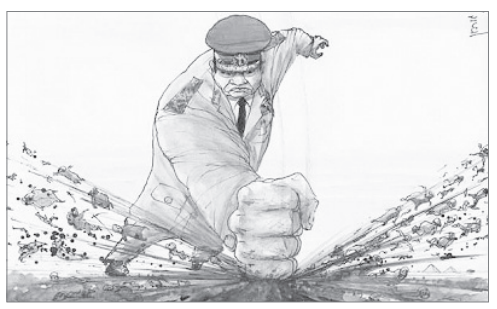

To date, only the Muslim Brotherhood’s Freedom and Justice has printed a violent caricature of Sisi. The cartoon was drawn anonymously. Usually pictured in sunglasses, the general is gigantic, with a bare face and an angry expression. His fist crushes an assemblage of humans, presumably anti-coup protesters, into a mess of carnage.

Freedom and Justice’s print edition, previously on sale at every newsstand, was scarcely available in Cairo a month after Morsi’s removal. Police had shuttered the paper’s offices, forcing the editorial staff to work clandestinely. In December, a day after the cabinet declared the Brotherhood an illegal terrorist organization, the Ministry of Interior announced that the publication would no longer be printed.

“I quit the newspaper after they got angry about that,” Andeel says of his colleagues’ rebuke. “It’s such a risk to make your life in cartoons in Egypt,” he says sarcastically, but adds, “I would have had to very intensely water down my language, be way more patient and pragmatic to deliver my message.”

There was too much material to stop drawing, even while looking for a new job. An audiotape of Sisi discussing nighttime visions leaked to the media, allegedly outtakes from an interview with Al-Masry Al-Youm’s top editor. In a recording too comic for words, Sisi recounted three dreams in which he had received omens of his presidential bid, including cameo appearances from President Anwar Sadat and an Omega watch.

In a cartoon entitled “Leaks… Dreams…” Andeel drew the general drooling in his sleep, on a bed floating in a pond of saliva.

During the past six months, Anwar has pushed the limits with Al-Masry Al-Youm. To be sure, he has drawn dozens of cartoons portraying the Muslim Brotherhood as violent, activating the terrorist trope—yet just as many break down the official stereotype. “The most important thing to me are regular people,” he says, “and not to say what they want me to say.”

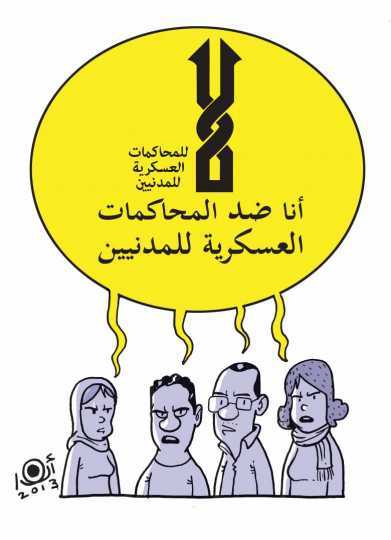

All the while, he sneaks in attacks on authority. In a radical cartoon from November, four Egyptian men and women exclaim, “I am against military trials for civilians.”

This past fall, the government floated legislation effectively outlawing political demonstrations; it passed in November. Congregating more than ten people now requires a permit, authorities must be alerted three days in advance, and police hold sweeping powers to break up unauthorized gatherings.

“I didn’t draw a policeman covered in blood,” says Anwar, who instead chose to emphasize the law’s absurdity. In a cartoon addressing the pending legislation, he sketched a chubby, oafish officer painting a red line around a youthful demonstrator, announcing, “And outside this area, I am not responsible for what happens to you.”

After the rules went into effect, he drew tear gas canisters falling from the sky like sleet, in an illustration entitled “Winter After the Protest Law.” It was a wake-up call to his readers that everyone is at risk when authorities arbitrarily crack down on public demonstrations.

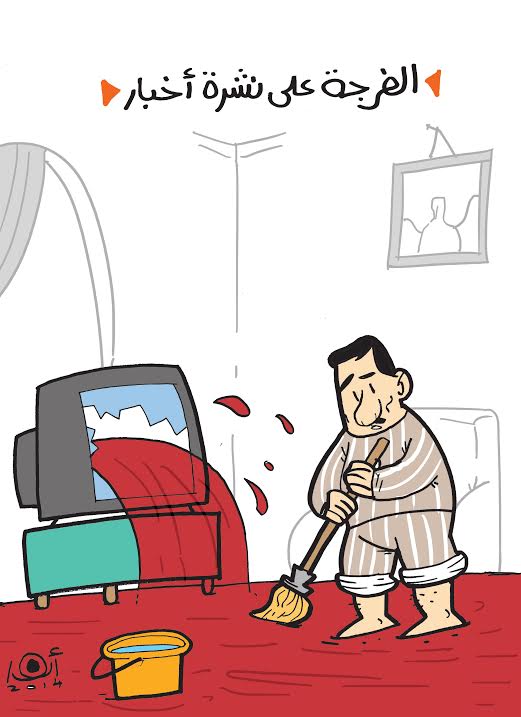

In February of this year, following two weeks of terror attacks in Egypt, Anwar drew blood flowing out of a cracked television screen, with a homeowner in pajamas mopping up the flood of red liquid.

In order to challenge readers’ entrenched opinions, Anwar offers straightforward imagery. “You are talking about a huge audience. The government cannot reach Sinai,” he says, referring to the area where terrorist attacks have escalated since the overthrow. “But I can reach Sinai. That makes me feel lucky, that I have my own weapon. The people in Sinai and Nuwaiba are not friends with me on Facebook, but they will see my cartoon.”

Andeel often works late into the night on TV scripts in The Program’s writing room. In broadcast media, where the audience is larger and even more hostile than any newspaper’s readership, Youssef’s show is going farther than any other program in challenging the government.

“Since I started at The Program, I have been having a lot of difficulties coping with these pressures,” says Andeel. He has encountered similar boundaries to the ones he experienced at the newspaper, the same tendency toward self-censorship given the military’s ascendancy and popularity. “At the end of the day, you are balancing and it is the same kind of equation. So the strategy right now is to slowly sneak until you get to Sisi.”

For those jabs that Youssef’s show won’t go for, Andeel turns to cartoons, which he publishes with the independent, online Mada Masr. One of his images shows an overly eager gunner marking the country’s ballot boxes far in advance of the presidential elections. “If they are going to send out every TV anchor and presenter to say the same thing, then you have to combine all of these mild messages and invert it,” says Andeel. “So it will be something impolite and naughty, speaking the opposite of what everyone is listening to every day.”

The same month, Anwar published a reaction to the monolithic media. A newsman interviewing a man on the street loses his cool: “Sir, when I ask you who you expect to win the presidential elections, pretend you don’t know… Pretend to think about it… Don’t respond straight away!!!”

When Sisi announced his presidential bid and resigned from the military, the retired general was finally fair game for Bassem Youssef and his team of writers. “It’s a long struggle where you have to calculate every move, every episode, and every joke,” explains Andeel. He’s learning to be patient. “Sometimes we would come up with jokes and be like, this is a really good one but we can’t use it this week. Or we can’t do this joke today because two days ago there were people killed in Sinai, so this will be disrespectful of—I don’t know what.”

Attempting to deviate from the official narrative, Anwar spars daily with the editor in chief of Al-Masry Al-Youm, and says he’s been pushed to present his political point more clearly. “If you are a fighter, you will find your own space.”

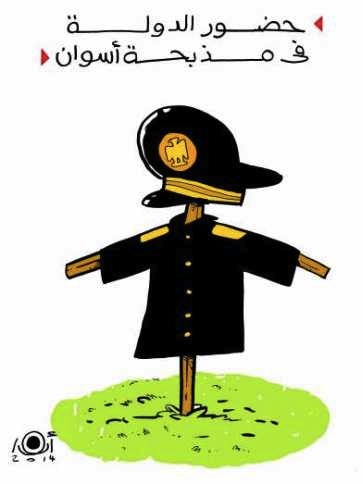

Like this cartoon from the first week of April, as tribal clashes in Aswan, in Upper Egypt, left over twenty-six dead. Anwar condemned the government and the military for their incapacity to ensure the rule of law. His cartoon of a military scarecrow reads, “State Presence in the Aswan Massacre.”

As Sisi follows Nasser’s course to high office, so too are young humorists waiting in the wings, elbowing out space for dissent in satire. Though they no longer share an office, Anwar and Andeel, along with their crew of cartoonist buddies, spend evenings together in neighborhood cafés, arguing over politics and talking shop.