As a child, Sara Rahbar was scolded for refusing to pledge allegiance to the flag. Her command of English was basic, and she didn’t understand why her classmates stood with their hands over their hearts. The flag returned to haunt her shortly after the terrorist attacks of September 11th. She was going to her parents’ Persian restaurant in Queens when her mother called to tell her that someone had threatened the family and ordered them to hang an American flag in the restaurant’s window. “It was a terrifying moment,” she remembers. “I looked for one everywhere, but I couldn’t find a single American flag. I returned to the restaurant with an image I found on the Web.” The murder of a Sikh man who lived in the neighborhood prompted Rahbar to stop speaking Farsi in public for a time. In 2004, Rahbar left New York City for London to study painting at St. Martin’s School of Art and Design; there, fueled by anger and loneliness, she conceived her first flag. (Slideshow here.)

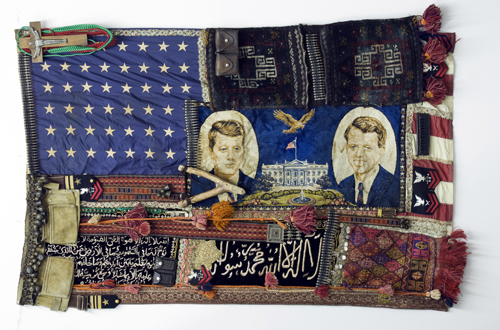

Little did Rahbar know that the piece of art would soon blossom into an acclaimed body of work that today includes forty-four hybrid Iranian-American flags made from fragments of Persian fabric, embroidery, gun saddles, and flagellation whips used by Shiite men during the month of Muharram. These works have become poignant metaphors for a large constituency of Iranians and Iranian-Americans in search of democratic pluralism, a compromise between Islamic faith and liberal values. Rahbar assigns melancholy titles to many of her tapestries such as Whatever we had to lose we lost, and in a moonless sky we marched, Flag #41 (2009), which will be on display from June 12th to September 12th at the Palais des Arts et du Festival in Dinard, France. She also currently has an exhibition at the Pompidou Center, on view until February 2011, which showcases her work alongside more than two hundred women artists including Frida Kahlo and Sophie Calle. Flag #41 depicts portraits of John F. Kennedy and Robert F. Kennedy beside a drawing of the White House, incandescent beneath a starry sky. The flag echoes her own journey to the United States shortly following the 1979 Islamic Revolution. For seven nights, five-year-old Rahbar and her family hiked through snow-covered valleys heading for Turkey en route to New York.

Today, Rahbar lives like a nomad, unable to commit to either country. She buys one-way tickets to Tehran and attends to her photographs and sculptures (she no longer feels safe traveling there with the American flags) until she’s struck by a visceral longing for the United States and the company of her mother and younger brother. “Someone asked me, ‘How do you decide to leave Iran?’” she says. “And I responded with the same answer Jackson Pollock once offered about recognizing a finished painting: ‘How do you know when you’ve finished having sex?’ I just know when a work needs one more tiny, yellow bead, and I just know when it’s time to leave Iran.”

The flags serve as poignant metaphors fashioned from fragments of Persian fabric, embroidery, gun saddles, and flagellation whips used by Shiite men during the month of Muharram.

Sitting in a Chelsea café on a cool Friday night, I ask Rahbar about President Ahmedinejad. She quickly covers her mouth with a hand, fixing her dark eyes on the recording device between us. The situation for artists in Iran is precarious: three young Americans are jailed, and the country remains in the throes of a political crisis; on the one-year anniversary of the June 12th protests that killed at least fifteen people, Rahbar worries about the future of the country to which she dreams of returning permanently. In her tapestries and photographs, Rahbar seamlessly combines disparate symbols and histories, but reconciling the cultures within the context of her daily life proves more difficult. “I’ll be searching for a home for the rest of my life,” she says.

After graduating from St. Martin’s in 2005, Rahbar began visiting Iran for long stretches of time. For the next four years, she turned to photography, collaborating with Iranian artists like rapper Yas and filmmaker Neda Sarmast, with whom she made Nobody’s Enemy (2006), a documentary about the youth culture of Iran. She traveled the country extensively, frequenting dusty bazaars in search of fabric for the patchwork flags she stitched and sewed feverishly. However, in a country where stringent censorship laws categorize artworks by the Islamic values of halal (allowed) and haram (forbidden), she seldom removed the hybrid banners from her bag. “I was making the flags, but I didn’t know what they meant. For a long time, I wondered, ‘what am I going to do with these flags?’”

In 2006, Rahbar was selected out of fifty-two artists to create a room-sized installation on the subject of war in the Middle East at the Queens Museum. Angry about the U.S. invasion of Iraq, she demolished the room with a sledgehammer and, with the help of her brother, drove bullets into the walls. Beside a kitchen table, rumpled underpants and broken dinner plates served as reminders of the civilian deaths caused by the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Above the war scene, she mounted Flag #1 (2006) as testimony to the pain she’s endured since fleeing into the mountains that dark, winter night.

“I’m still confused,” she admits. “The journey was traumatic, and we risked our lives to come to a country my father once idealized.” Eight years ago, her father left the family and returned to live in Iran.

Rahbar channels her confusion into a recent series of performative photographs titled, Love Arrived and How Red (2009). “I shot the photos in Iran during a dark time,” she says. “I found myself very alone.” The photographs depict a soldier in Iranian military cords and a bride (Rahbar) in a western wedding gown with the American flag for a veil. The couple stands before a black background, their faces concealed by hoods with cutouts for their eyes, nose, and mouth. In one composition, the soldier holds his bride over an American flag, symbolic of the sheets a groom’s mother inspects for blood the morning after a traditional Iranian wedding. The pose juxtaposes the taboo of sex in post-revolutionary Iran with the relative sexual freedom in the West. In the final photograph, she presents herself as a dead bride holding Iran’s fruit of paradise, a cracked-open pomegranate with red seeds spilling from her hand.

Her tapestries and photographs attempt to unravel the intertwined fates of America and Iran and all those caught up in the quarrels between the two countries.

Last June, after attending the international contemporary exhibition Art Basel in Switzerland, Rahbar returned to Long Island and watched on television Revolutionary Guards attack unarmed men and women protesting in the streets of Tehran. Leading up to and following the election, several large-scale exhibitions dedicated to Iranian artists went up at the British Museum, the Saatchi Gallery, and the Chelsea Art Museum, where Rahbar displayed Kurdistan, Flag #5 (2007). Shows like * Iran Inside Out*, which showcased the works of fifty-six artists—more than half of whom lived in Iran—offered insights into a culture that has become increasingly opaque ever since international journalists were banned from the streets last summer. Rahbar is conflicted about these group exhibitions and expresses concern about the art world’s interest in her as a young Iranian-American. “I don’t want to be a fly-by-night artist, recognized by curators because my country’s on fire. That’s a terrible thought,” she says. “My work is foremost about the human desire to belong; it is not a statement about growing up Iranian-American.”

While Rahbar’s work primarily addresses her own struggle to identify with an old and new homeland, her tapestries and photographs also speak to a struggle on a larger scale. As relations between the countries become increasingly fraught over nuclear weapons negotiations and tougher multilateral sanctions against Iran, Rahbar’s work emerges as a complicated attempt to unravel the intertwined fates of America and Iran and all those caught up in the quarrels between the two countries.

Rahbar can’t say how she’ll divide the rest of the year working between Tehran and New York City, though she predicts she’ll continue sewing flags until she settles down somewhere. For now, she plans to focus on a new body of work which she’ll include in an exhibition scheduled later this year in Italy. “My relationship to Iran is like a woman who is head-over-heels in love with her cruel husband,” she says. “The idea of living without him hurts more than the violence, so she stays and tolerates his brutality. I often leave Iran feeling exhausted and beat-up, but I can never stay away for very long.”

See the Flags slideshow here.

Tamzin Baker is a writer living in Brooklyn.

Author’s Recommendations:

The films of Jafar Panahi and Kyle Goen.

Panahi, who is known for politically charged films like The Circle and

Offside, (he won the Golden Lion at the Venice film festival for

Circle) was jailed back in March for shooting a film about the 2009

presidential election and the protests that followed. While the French

government recently called for his release, the Iranian culture minister

continues to defend the arrest.

Goen is an up and coming mixed media artist who just had a solo show

called “The Voice That Arms Itself to Be Heard” at Dash Gallery. I was

most taken with one of his flags and he and Rahbar, I think, have quite

similar intentions.

To contact Guernica or Tamzin Baker, please write here.