Four years after Hurricane Katrina, writer Pia Ehrhardt, a New Orleanian before and after the storm, has guest edited our September issue culling art of all genres with the hopes of identifying how New Orleans is healing.

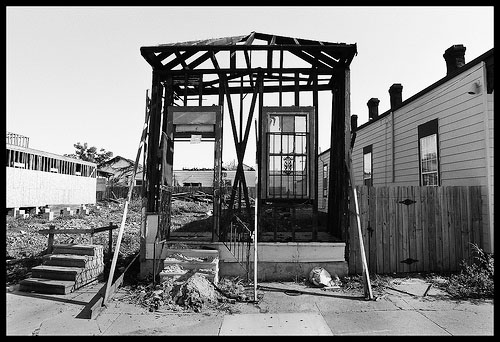

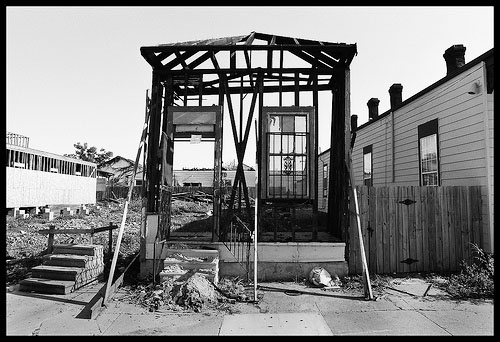

When friends from out of town come to visit, my husband, Malcolm, and I put them in the car and drive. Driving is the only way to grasp what happened, what is happening, and what is not happening in New Orleans today. We drive for hours and see nothing but flood-damaged neighborhoods: from the 17th Street Canal to Lakeview and down to St. Bernard, from Treme to Gentilly and over to Slidell. Some houses are being rebuilt, but right next-door unoccupied homes are in limbo for a jack-o-lantern effect.

Photo by “Ryan Thomas”:http://www.flickr.com/photos/ryanthomas/ via Flickr

Our visitors have questions, concerns, until the number of affected blocks sinks in and they go quiet. In the Lower Ninth Ward, they ask us to stop so they can get out and walk up to stoops that now lead nowhere, look at blocks with ten-foot weeds that have returned homesteads to farmland. Some cry. All of them are humbled, stunned, and saddened. “I had no idea,” they all say. This is the reaction we want from people who don’t live here. This is the ground’s-eye view.

Before Katrina, Orleans Parish had a population of 480,000. Four years after the flood, estimates say it’s back up to almost 351,000. But many of the people being counted are newcomers, such as the Hispanics who came in to gut and build homes, the public school teachers, and the young people who came to help and stayed because they enjoy the city and want to work here. We’ve effectively lost New Orleans East, where many of the black middle class resided—our teachers, nurses, mailmen, managers, and policemen. Much of the poor lost, first, their houses, and then, their way back home. And while our numbers are fewer, our per capita murder rate is the highest in the country. Approximately sixty percent of New Orleans children now attend charter schools, the highest percentage in the nation.

I wasn’t able to write about Katrina until recently. For one thing, the damage and loss and pain are deeply personal. After the flood, my son’s high school, eleven blocks from our house, was under eight feet of water. My stepson Marc’s first home in Lakeview sat under nine feet of water. He’d been married just a year, and his wife was pregnant; their daughter Lucy was born two weeks after Katrina. My mother-in-law, her 86-year-old sister, and my sister-in-law, all had to gut their homes, which had sat baking in shallow water and filling with black mold. For nine months, they lived in their driveways in FEMA trailers, waiting for their homes to be rebuilt. “I’m too old for new appliances,” my mother-in-law said. “What a waste.”

Beyond the personal, the consequences of a faulty levee system are too far reaching to comprehend. Nature, okay, we yield to, but the flooding didn’t have to happen. Now, it’s hard not to feel powerless when there’s so much to be done.

When Guernica asked me to guest edit an issue on the fourth anniversary of Katrina, I decided to include writers and artists who’d lived in New Orleans before and after Katrina. I wanted work from people on the ground who experienced her first-hand, and who then came back to go to school, to teach, to help in the rebuild. I wanted work from people who were ready to talk about what happened head-on, or not. Some of us may not be writing about Katrina, but we are writing after her, and the loss and anger and frustration are fuel.

Through the words and images of the artists listed below, I understand how Katrina fell on them, even four years later. It’s so easy to think things are back to normal because this is where it gets complicated, writing about the rebuild of this resolute, inimitable city, because progress is slow-going. Yes, my neighbors came back, my son’s high school was renovated and he’s in college now, and after four years of wrangling with insurance companies and Road Home grants, my stepson and his wife will build a new home on their lot in Lakeview. When I walk through City Park, I see volunteers in bright tee shirts picking up trash and planting irises in the bayous. When I read the morning paper, I see stories about schools and businesses re-opening, about New Orleanians sick and stuck and depressed as they try to get home, and commentary from experts and pundits from not-here weighing in on how we can get it right this time. We appreciate help from outside, but we don’t want to be told how to live.

As Sarah Shachat, one of my students at New Orleans Center for Creative Arts, put it in a piece set on a disaster tour, a macabre tourism offshoot: “When we get to the Ninth Ward, we are taken straight to the Musicians Village, an Easter-egg basket of brightly colored raised houses built by Habitat for Humanity in the Creole style. Little plants suspended on chains sway in the air, but there’s no other movement or sign of life in the pink and periwinkle buildings. My head pounds from the flow of processed air as our guide, Bart, informs us that this area ‘was not fiscally sound before the storm, but projects like the Musicians’ Village aim to energize a renaissance.’ Not fiscally sound. That statement is about on par with saying that a rotting parrot is currently life-challenged. The Ninth Ward had sunk below the poverty line long before Katrina.”

It’s expected that the rebuild will take ten years. Pre-Katrina problems must be fixed. Post-Katrina problems must be fixed. There’s a list a mile long of things to do. Not everything can be blamed on Katrina, but she’s given us a place to begin.

What I hope the writing in this issue offers you are images and stories that give you pause and good reason to remember we are still down here, moving ahead, holding strong, but not moving on if it means forgetting what can happen.

**The Work I Have Chosen**

After years of working in advertising and PR, I left the profession to write full time and teach at New Orleans Center for Creative Arts (NOCCA), an arts training center for high school students with talent in music, visual arts, theater, media arts, and dance, which pulls from seven parishes. The Marsalis brothers went to school there, so did Harry Connick, Jr.; graduates leave and go on to music schools, to design schools, to creative writing programs. It’s competitive and an honor to be accepted, and it’s a gift to teach there and work with confident, engaged students who, in the essays excerpted from Running Home: True (Enough) Stories From In and Around New Orleans, a book initiated by teacher, Anne Gisleson, take hold of what’s going on down here. In Are We There Yet?, Monique Thomas takes us into New Orleans East after the storm; Daniel Hoppes discovers New Orleans and himself in Pedaling New Orleans, and Aaron Friedman, in Hitler’s Horse, explains what it’s like to live in St. Charles Parish, away from what happened geographically, but not emotionally. There’s no place to hide. NOCCA sophomore Avery Friend wrote about Katrina from the northern shore of Lake Pontchartrain, twenty-four miles from New Orleans, a safe distance in theory only: “After the storm, my friends and I strolled along the sidewalk by the water, walked out onto the long concrete fishing ridge, and watched the sunset. As the sun sank into the lake, I pictured a city beneath the still surface, quiet and empty, and I didn’t let my feet touch the water.”

My colleague at NOCCA, Ken Foster, is a writer, an activist, a pit bull advocate, and the father of five dogs who found him. His short story, Albino, nails the eerie surrealism of living under a tarp in the desolate Holy Cross neighborhood down in the Lower Ninth Ward.

Barb Johnson is my Mid-City neighbor. For thirty years, she was a carpenter, and when her shop on Palmyra took on twelve feet of water, she went to Plan B: graduate school at the University of New Orleans where she wrote stories that would become her first collection. Keeping Her Difficult Balance takes place on Bayou St. John and is about people on their way either to or away from something.

Angelica Robinson, a 2009 NOCCA President Honors Recipient and a NOCCA student last year, wrote N.O.A.H., a short story that is brave, authentic, and devastating.

The creative writing program at Lusher High School is run by poet Brad Richard whose work is also in this issue. I’ve taught workshops there, and I’ve been flummoxed, and made jealous, by the fearlessness in his students’ work, including Taylor Yarbrough’s His Only Begotten Rat, Elizabeth Lilly’s Scenes from the Highway, Cora Parsons’s Evacuation, and Jeanette deVeer’s Spirits of the Storm. Adam Gnuse’s short-short story, The Dead Man, I warn you, may rattle your brain.

Poet Andy Young is also a colleague at NOCCA and the editor of a bilingual literary magazine called “Meena”:http://www.meenamag.com/. Her poem Snapshot is set in El Salvador, and is part of a recently completed collection called _Rope of Salt_. She lives in New Orleans with her husband and their (now two) small children.

Poet Mark Yakich breaks my rule of having lived here before the storm because he came to New Orleans after Katrina to teach at Loyola University. His poem cycle Green Zone New Orleans, published by Press Street, a locally owned press, was originally performed as nine voices in unison, which can be heard here.

Brad Benischek is a visual artist and teacher who kept a graphic journal while he evacuated with his family. Four years later, too many of his pages about homelessness and bureaucracy and lousy leadership still ring true. The book from which these pages came, Revacuation, is smart, spot on, and not well enough known.

**Pia Z. Ehrhardt** lives in New Orleans with her husband and son. Her stories and essays have appeared in _McSweeney’s_, _Mississippi Review_, _Oxford American_, and _Narrative Magazine_, and have been anthologized in New Sudden Fiction: Short-Short Stories from America and Beyond

**Pia Z. Ehrhardt** lives in New Orleans with her husband and son. Her stories and essays have appeared in _McSweeney’s_, _Mississippi Review_, _Oxford American_, and _Narrative Magazine_, and have been anthologized in New Sudden Fiction: Short-Short Stories from America and Beyond and the 2010 edition of _Writing Fiction: A Guide to Narrative Craft_. Her short story collection, Famous Fathers and Other Stories

, was published by MacAdam/Cage (June 2007). Her work has been featured on NPR’s Selected Shorts and can be heard on KQED radio. She is the recipient of a Bread Loaf Fellowship and the 2005 Narrative Prize.