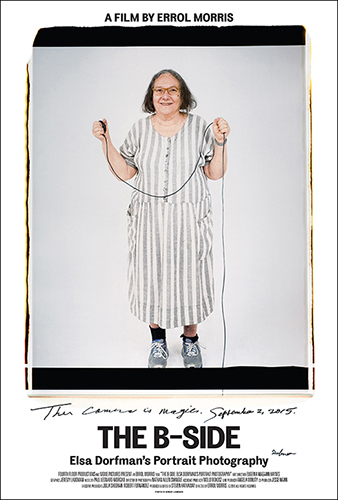

In the landscape of professional, amateur, accidental, and occasional photographers, almost nobody takes pictures like Elsa Dorfman. This is because what Dorfman has been compelled to do since the 1980s is kneel beneath the 200-pound Polaroid 20×24 camera and deliver from it its enormous prints, one after another. The process looks natal, but the trouble with the 20×24 is mechanical. Following a bankruptcy filing and a tortured restructuring, several years ago Polaroid stopped making instant film. Dorfman is about to run out of film stock. Errol Morris’s amiable new documentary, The B-Side, screening at the New York Film Festival this month, is meant in part to forestall the extinction of stock and camera by drawing attention to Dorfman’s body of work and ends up serving, in part, as a retirement gift to the 79-year-old portrait photographer. A close friend of Morris’s, a lifelong pal of Allen Ginsberg’s, and an obdurate optimist, Dorfman is a woman whose output Morris calls “a perverse combination of dime store photography and Renaissance portraiture”—not a minor Beat but a mild postmodernist.

Ginsberg is the subject of many of Dorfman’s photographs and indirectly responsible for leading her to the 20×24; for the privilege of using the rare and coveted camera, she promised Polaroid a shot of her friend, the famous poet. Elsa and Allen had “met cute” in 1959 at the offices of Grove Press, where she was a secretary and he was “looking for the can.” Their friendship continued even after she left New York and returned to Massachusetts. (Dorfman is Tufts-educated, Boston-born.) In those days Ginsberg was well into his vocation, but Dorfman was still in search of one. Only at twenty-eight did she first pick up a Hasselblad.

Here is a woman neither humble nor vain; a working photographer and not really an exhibiting one.

There’s more, but writing it here would be repetitive. The anecdotes of Dorfman’s life are easy enough to find on her charmingly outmoded website and in articles citing her as one of the few photographers to work extensively with the 20×24—a camera to which Dorfman is drawn because, she says, it’s “magical” and “unpredictable.” But these stories are best heard from the source, in Morris’s film. Here is a woman neither humble nor vain, a working photographer and not really an exhibiting one. “I’m totally not interested in capturing people’s souls,” she says, and in seventy-six minutes spent mostly in her studio, we see her real interests as she shows Morris her prints, including the “B-sides,” shots customers have left behind: couples, accidental gestures, her husband, a flower, a balloon bunch. In younger years, shooting in black and white, she photographed the light at night, her friends, and herself, unsmiling, a cable release bisecting the shot. Later she began adding captions.

In The B-Side, Morris obeys Dorfman’s formal injunction to look only at the surfaces of things. Like Dorfman, who tells her paying subjects to bring their pets and instruments—their fetishes, idols, familiars, charms—Morris shoots his subject in her usual sneakers and patterned top, surrounded by her archive. For once, there are no reenactments and no Interrotron (Morris’s camera-teleprompter interviewing rig). But he also disobeys the directive, because he’s making his own film and not a mock-Dorfman. What is Elsa Dorfman’s archive if not a soul? Here are her methods, her practice, her mistakes, her A-sides. Pulling photos from the flat file, Elsa Dorfman shows us the development of her own life: Ginsberg and Dylan, Borges and Anne Sexton, countless strangers playing at being themselves for the enormous camera, her parents, her husband, and her son.

About the Communist meetings of his childhood, to which his mother took him, Ginsberg wrote “they sold us garbanzos a handful per ticket a ticket costs a nickel and the speeches were free everybody was angelic and sentimental about the workers it was all so sincere you have no idea what a good thing the party was in 1835.” Documenting family may be an act of love and deliverance for Dorfman, but within the context of Karl Marx City, another documentary screening at the Festival, a family photo can be the embodiment of a curse. In the subject of Karl Marx City—Communist East Germany between 1950 and 1989—the party was a pretty bad thing, and no angels sang. The documentary is full of photographs that are profoundly less endearing than Dorfman’s because they were taken without knowledge or permission by agents of the Stasi secret police or the thousands of citizen-informers who worked for them.

Directors Petra Epperlein and Michael Tucker have a personal interest in delving into the warren of documents the Stasi left behind. Epperlein grew up in the German Democratic Republic, in Karl-Marx-Stadt, with her parents and twin brothers. She moved to the United States in in the 1990s, but her family stayed put, and in 1999, after sending Epperlein a strange and final letter, her father hanged himself. He had been receiving strange letters himself, as it turns out, accusing him of being an informant. Karl Marx City follows Epperlein as she comes home again, carrying a boom mike around the streets of Germany like a flag. She is trying to learn whether her father did indeed collaborate with a regime that not only kept its citizens under constant surveillance but sold the less desirable ones—the dissidents—to the West when it needed money.

It isn’t like Schindler’s List, Dr. Knabe says, because there’s no record of a Stasi Schindler.

The black-and-white doc’s punky aesthetic—Barbara Kruger-style text introducing the steps of Epperlein’s investigation, interspersed with footage discovered in the Stasi archives—can seem weirdly irreverent for a film about a parent’s suicide and a people’s suffering. However, normalizing aberration may be the point. Historian Douglas Selvage, one of the film’s many talking heads, points out that in the Republic “by being a hero you condemned your family to a terrible fate.” In such circumstances, many East Germans were at least occasional “collaborators.” The father of Epperstein’s childhood friend Yana was actually a Stasi agent and explains his career choice on camera: he, at least, had faith in the Communist cause. Another interviewee, Dr. Hubertus Knabe, a consultant on The Lives of Others, recalls telling the director that his main conceit—a Stasi agent developing sympathy for the surveilled—was too far-fetched. It isn’t like Schindler’s List, Dr. Knabe says, because there’s no record of a Stasi Schindler.

Epperlein is not after a poetic truth, only one single fact.

Epperlein shows us miles and miles of Stasi records as well as bags of shredded documents still being pieced back together by hand. These files can be opened to researchers and to those named in them (as well as to family members), but one archivist warns Epperlein that documents are both difficult to find and to understand because the system into which they were designed to fit is gone (a bit like the difficulties encountered by religious strict-constructionists). The problem is also that that system was always a failed one. The Stasi’s record-keeping—who went where, said what, what was implied—was a doomed attempt to imagine the souls of citizens. Despite Dr. Knabe’s critique, that’s only possible in art. And life in an absurd system already resembles art: for instance, all of Epperlein and Tucker’s talking heads can’t outshout the silent and immobile head of Karl Marx. A voice-over tells us that the head weighs forty tons and cannot be removed from what was Karl-Marx-Stadt: the city is called Chemnitz now. Bronze immobile Marx just sits there, like a bad omen. In 2006, the BBC reported that Chemnitz had the lowest birthrate in the world.

In Ginsberg’s poem, the communist idyll is undone in hindsight: “Everybody must have been a spy.” But Epperlein is not after a poetic truth, only one single fact. The answer she finally gets about her father has to do with a signature found in a Stasi file—a caption of sorts, apt evidence for Susan Sontag’s idea that “photographs wait to be explained or falsified by their captions.” Most useful, then, is the voice-over telling Epperlein’s story. It’s a clipped, true-crime sort of narration that develops a very different echo when the credits begin and one realizes it has been Epperlein and Tucker’s daughter speaking: a child of two directors, born in spite of the past and under the sign of the camera.