1. Now, I’m Disney

The bear’s eyes are green. Jim’s are almost black, dark little beads. The ER, Wednesday morning. Jim’s on his way home. Me, too. Jim doesn’t say what brought him here. Me, it was the usual: my troubling heart. Or maybe just its echo. Distant now from the heart attack that nearly did me in, I still feel the ghost. “Phantom pain,” they say. Slicing down my left arm, straight through the hand. “Just a little PTSD,” guessed the attending who came to visit my hospital bed at 2 a.m. The ache in my sternum made him wonder. Spreading between my shoulders like a cold hand. “You did the right thing,” said the doctor. He meant calling; he meant coming in, after the kids were asleep, so they wouldn’t notice me gone. “Don’t take chances,” he said. “Given your history.” But chances, not history, are what we’re given. That which we receive, if we’re willing.

Awake, 3 a.m., 4 a.m., my eyes resting on the curtain between my bed and the hall, grateful for the softened light, like a sunrise not yet arrived.

Sixteen hours. Electrodes, blood draws, IVs, X-rays, treadmills, ultrasound, oxygen tubing wrapped around my ears, nitro hot beneath my tongue. What remains? “Phantom pain.” Or maybe it’s real. The nurse-practitioner considers. “It’s hard to say.” She—“we,” the hospital speaks in the collective first person—can’t offer certainty. What they—we—have is “confidence.” She, they, we all realize that word, confidence, it’s a gamble. A good bet. Excellent odds. It’s a confidence game. Take it with you, when you leave.

“Bear hunter?” I ask Jim on my way out.

“Used to be,” he says.

“That’s a big one,” I say of the mug on his arm. He agrees. I ask for a picture, suggest he step into the sun. He agrees to this, too, but he shuffles backward, into the shade.

“Everything I did was bears,” he says.

“What happened?” What I want to ask is, Was it your heart? Sugar? Your lungs?

“Kids,” says Jim. “Now, I’m Disney.” He shows me his other shoulder. A tattoo just as grand, finely drawn: Mickey, Fantasia, the beaming mouse in purple wizardry. Jim turns back, looks down at the beast: “Just a memory,” he says.

2. The Word

He could not remember the name of the drug. Sometimes he asked for “migraine.” Once for “a midfielder.” Usually, he said nothing. The nurse, summoned by the call bell, would wait. He would try to make a fist, to grasp the name, but his fingers had swollen. The nurse would understand. The drug would flow, and sleep would come, until it did not anymore, and then he would have to reach for the word again.

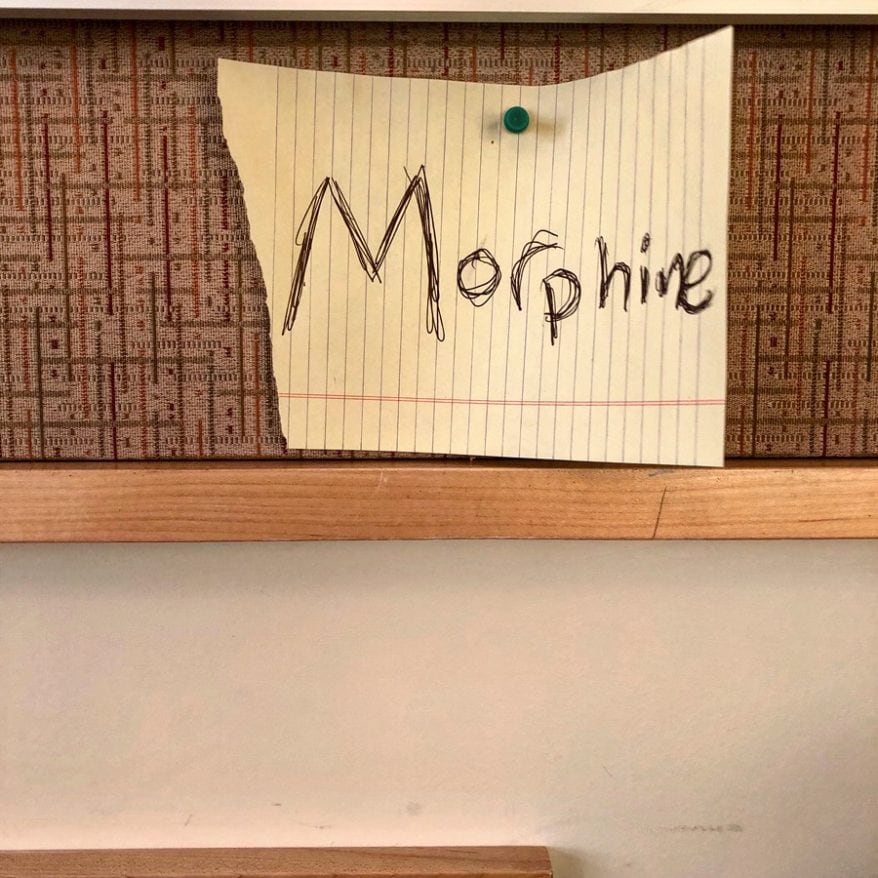

Finally, hands shaking, he decided to write it down. “Tack it at the foot of the bed,” he instructed. Still he could not remember. It was perplexing. He knew it was not his mind that was failing, only his body, and he’d never cared much about that. His life had been one of words. For half a century, he’d been making books. He was making one now, when the drug allowed, working by dictation, and for that the words still came. He had so many.

Maybe he could locate it by sound. M. “Mortgage”? No. The nurse would not give him a mortgage. “Memory”? That was the goddamn problem.

Once, when he’d been given the drug, after it had slipped into his veins and spread across his failing body like a blanket of no temperature, he had pointed to the scrap of notepaper tacked to the wall and asked, “Is that a map? Of the Middle East?”

“No,” we said.

He pondered this. “Strange,” he mused.

“Motrin?” No. “Mor-mor-mor — Mormon?” No. “Mortuary?”

The word. The word. The word. “Mo-mo-mo. M-m-m.” Warmer. “Mmm. Mmmmm.” Yes. Sleep now, brave man. The words await you.

3. The Words

“These are great,” says my friend Jo, a photographer, looking at these very pictures, spread across my desk. “Except that one,” she says. This one, she means. “That one’s boring.”

“But look what it says,” I tell her.

She leans in. “Oh, well, that’s interesting.” She sees the reflection. My reflection. “Because it’s you in the picture.”

“But the words,” I say.

“Morphine,” she says, reading the word that comes before.

“That’s my father.” I point to the picture that will follow this one, a carnival ride, “Rockin’ Tug,” a boat that swings up into the sky. “And that’s my daughter.”

“I see that.”

I say, “and look at the words.”

→

←

ALL THINGS ARE

DELICATELY

INTERCONNECTED

“Oh, right,” says Jo. “And it’s like you’re praying.”

“Praying?”

“Your hands. When you take a picture with an iPhone.” Jo demonstrates: clasping her hands like mine. “A prayerful position.”

4. Three Tattoos

Late in the afternoon I took the kids to the Tunbridge World’s Fair, which is really a big county fair in Tunbridge, Vermont. Farmers and carnies, a chance to buy a new truck or a tractor, or to sit in the cab and dream of doing so before trudging off to the pig race or to the tribute band stage. Mötley Crüe and AC/DC sound-alikes, beer, sweet Italian sausage and rides that hurl you hard into the whitish September sky, gentler possibilities for your children.

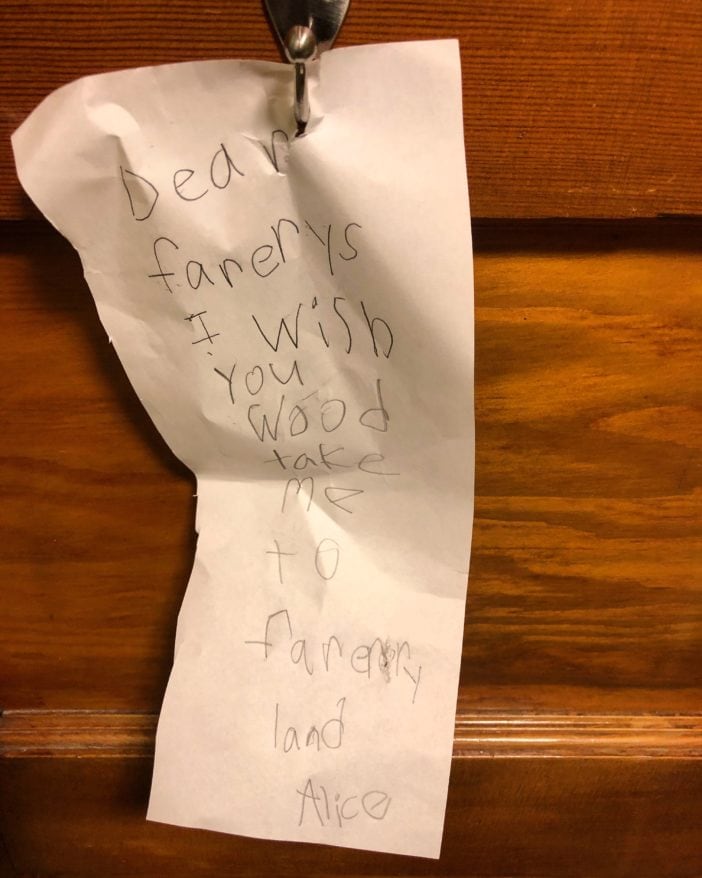

I counted three dead baby tattoos—a face, dates—and stopped counting men missing limbs. I marveled over the flags and gun logos. T-shirt: “Stomp on this flag, I’ll stomp on your ass.” A lot of “2nd Amendment: The original homeland security.” Fair number of Trump shirts. Many rides for the children, my son’s first mini-rollercoaster, blue-ribbon sheep, remarkable sows. An ox named Zeus, who was worthy of that name. Then I drove the kids home, and in 15 miles, passed three cars. We stopped in the middle of the dirt road that drops us at our house, just past the sign that declares “Pavement Ends,” turned off the lights so we could look with earnestness at the harvest moon. At home, my daughter taught her little brother how to put shoes on the front porch to be filled with coins from the Moon Faery.

“Does the Moon Faery live on our road?” my boy asked.

I considered for a moment. “Yes,” I told him.

5. Three Different Roads

Lloyd tells me three different roads to get to Morrisville, Vermont. “Which,” he adds, “you don’t want to do that.” Lloyd was born there—“Morris,” he says—but now he lives in Jeffersonville: “Jeff.” He lost his job at the sawmill—“Ash,” he says, “dries your hands, cracks ’em to the bone”—and then his job as a dishwasher, and then his home. Now he’s sick. This is where the county put him.

There were farmers in his family, but never Lloyd. “I weren’t,” he says. “I don’t speak French, neither.” The two together in his mind, farming and French, Vermont-French. “There’s more of it than you realize.” He never learned. Not French, he says, nor computers. No chance for the old ways, or the new. The old is the new now, he says: “Corporate,” by which he means the fate of the farms, bought up, “megabucks,” five or six or a dozen family farms under one hand. The computers, though! Have I seen how the kids use them? “They block you out. You say, ‘Son!’ Or, ‘Daughter!’ They block you out.”

You have kids, Lloyd?

A daughter and a son. “She’s gonna be 18. And”—he pauses—“second or third of August our son’ll be 14. We don’t have ’em anymore. We lost ’em to the state.”

I don’t ask. Lloyd says. “Some people made comments about us. But other people what was worse than us got their kids back.” One couple got their kid back, and then: “The state worker never bothered to ask.”

Ask what?

“They said the kid was sweet.”

Sweet?

Asleep, he means to say. “They never bothered to just peek in on him. And the kid was dead.”

Lloyd has a question: Do my kids learn the computers? My daughter does. Good, good. “And teach her the roads,” he advises. “Take a map. Say, ‘We’re here. Can you find a way?’” Set her to finding three ways. Anywhere to anywhere. Norwich to Burlington. Morris to Jeff. “Tell her to see if she can find different roads to get you from here to there.”

The idea feels urgent.

He sees his kids once a year.

“Most roads,” he says, “leads you from here to there. Not all roads. But most roads take you wherever you want to go.” He considers for a moment. “Most of the time.”

6. This Note

My wife dropped me off for an appointment with my doctor, and afterward I walked a mile and a half down the road to the nearest town, where I would wait to be picked up at the library. The news from my doctor wasn’t bad, but also less-than-good, a reminder that it’s not just my heart that is vulnerable. Just a reminder, not even a warning. Still. We are, of course, dying from the minute we’re born; only sometimes are we given hold of this simple fact, banal and yet so distant from our daily being.

On my walk I passed a turkey farm where I remember, three years ago, a week after my heart attack, pulling over. To look. Now, I couldn’t tell you what the turkeys meant to me, then. But I remember, like a song you can’t forget, the ribbon that wrapped itself around my chest as I stood before them, and squeezed, and the pain that whispered down my left forearm and out my pinky. Then the pain was gone. Just me and the turkeys. I got back in the car and asked my wife to return me to the hospital. There I spent another 24 hours, took again all the tests and passed them, and then I went home, no more certain than I’d felt upon admission.

“Admission.” Funny that we use this word to speak of entering a hospital. As if it was an honor for which one applies.

Now, walking down the road, past the turkey farm and past a field heavy with turkey vultures above—what dead thing lay in the tall grass?—and past crows, silver-winged beneath cloud filtered sun. Then the library. In the basement I waited for the bathroom. A little girl, seven, maybe, emerged and darted up the stairs. Inside, left behind, this note. And now, at night, I tap this out with my thumbs, my five-year-old asleep beside me after he has listened to the poem that has become his favorite, as it was his sister’s before him: Come away, o human child / To the waters and the wild / with a faery, hand in hand…

7. The Ice in My Eye

All my night walks, and I’ve never seen this before: ice crystals kaleidoscoping across my left eye’s lashes, silver-and-blue just like the moon. When the moon rose big and white early this evening, our little boy, marveling, called it a pumpkin. Maybe he was thinking of those white gourds we bought him? Our ghost pumpkins?

The ice in my eye does not look like a pumpkin. It looks like tiny toy soldiers, marching in sharp new uniforms, silver-and-blue, too pretty for war. I wish you could see them! So dazzling. I wish I could show you what I really see now, just shy of tomorrow, holding my phone up to the sky to take a grainy picture.

Deer clatter across the frozen ground, hard as earth-pale bone. I blink. The ice disappears.

I wish I could show you the brightness that grew just like ice in the middle of my left eye a week ago. Like a pond crackling frozen beneath a warmthless sun. I wish I could draw through your vision the curtain of rain that then cut across what sight remained. It seemed to me—after my vision returned—that I’d witnessed something beautiful and rare. That maybe this was not a stroke or a migraine, that maybe I was lucky.

When I could see again, in the emergency room, I watched that toothless man in the ragged red t-shirt who sat across from us while we waited. Younger than me, and yet his face collapsing. Like those pumpkins we both left to rot in the front yard straight through November.

You like pain; so do I. I wish I could paint a stripe of it down your left arm, down to the end of your pinky. Spread it like ointment across your breastbone. Not like that night I felt as if I was drowning. That night when I woke you and said, “I think this might be what they mean when they say, ‘A sense of impending doom.’” Not that. The aftermath. Its echo, its shadow. I’ve come to like it, when I walk into the night and it vanishes. I like to leave it behind.

You think you like pain. So do I. I wish we could be certain. About its echo and its shadow, about what it means to see and to be seen. I wish I could show you all this icy light in my eyes.

You like to walk alone in the dark, too; I wish I could see your night visions.