As the Lady Maria drifted along the Mediterranean Sea in the direction of Italy and Bassem watched Lebanon shrink away, he felt a combination of slighting contempt and triumph. The docked ships at the Port of Tripoli were the first bits of his homeland to vanish, and the bullet-holed high-rise buildings were the last. If the glistening waters were able, they would have whispered to Bassem that September afternoon that he should reconsider.

Bassem was a fisherman, but he had never embarked on such a journey. Still, he bet, as he often did, that the sea would abide by his wishes—after all, those same waters had been there for him in the past when the government hadn’t. So he let a gust of cool breeze flow over him. He smiled, squinting beneath a raging sun. The boat, which once ferried tourists, was moving steadily. All was well.

“I felt pure joy,” Bassem told me later. “I was afraid of nothing.”

Just before the Lady Maria exited the port, the small ship and its 32 hidden passengers reached a security checkpoint. The Lebanese army raided the boat and discovered dozens of water bottles, tuna cans, packs of bread, boxes of Picon cheese, and life jackets. “If you don’t let us leave,” Bassem threatened, “I’ll hang myself.” He tied a length of rope into a noose as he spoke, an implicit threat. “I had nothing left to lose,” he remembered. “Only my spirit.” The soldiers made some calls and then relented.

Freely sailing in international waters at last, Bassem took off his red t-shirt, emblazoned with the Arabic words “SOVEREIGN LEBANON,” and threw it into the sea, even though he’d only brought one other substitute. He tossed another traveler’s Lebanese flag overboard. Bassem guffawed as he watched the items float away. This was what it felt like to rid one’s self of one’s baggage. This was what it meant to have nothing left tying you to Lebanon.

A month earlier, Bassem and twelve other middle-aged Tripolitan men met at a café to strategize, between sips of Turkish coffee and drags of shisha, about getting out. They were plumbers, builders, and bakers, none of this by choice. The latest economic crisis had ravaged them. Bassem, a forty-eight-year-old divorcée, earned, at most, the equivalent of $60 monthly—barely enough to cover his rent. Deep in debt, he was broke and broken. So were his friends.

The same day, 2,750 tons of improperly stored ammonium nitrate exploded at the Beirut Port, ripping apart a city that was already coming undone. The blast killed roughly 200 people, maimed around 6,000, and left some 300,000 homeless. The news that evening aired footage of apocalyptic destruction and its bloodied survivors, a visual testimony to the economic and human cost of the state’s malfeasance. The city seemed to Bassem as broken as he felt; the eerie mirroring removed any doubt he had felt about leaving.

Now, Bassem’s gaze darted from his cast-off t-shirt to the boat deck, the horizon, the skies. He watched some of the fifteen children on board the boat play, and he thought of his own. He had left all five of them, aged ten to twenty, behind. After spending the eve of his departure staring at the cracked ceilings of his apartment, pondering how the trip might go awry, he departed at 7 a.m., without uttering a word to them. “They’ll soon follow me, after I settle down,” he consoled himself, trying to keep the guilt at bay as he softly closed the door behind him.

Lebanon is forever “on the brink,” barely steadying itself after any given crisis before yet another tragedy hits. Since 2005, the country has been ruptured by political assassinations, a war with Israel, sectarian violence, and successive corrupt governments. In 2015 a waste management crisis poisoned the air, and in late 2019 wildfires gutted the mountains, destroying much of the tiny country’s natural beauty. Lebanon became home to more than one million refugees from neighboring Syria, making it host to the most refugees per capita in the world. Their arrival, beginning in 2011, compounded a xenophobic political discourse, with some Lebanese accusing the refugees of further straining the already strained country.

Rising unemployment and economic collapse rooted in governmental mismanagement would ultimately bring the exasperated Lebanese population to its knees once again. In October 2019, to boost dwindling revenues, the ruling elite declared taxes on gasoline, tobacco, and the use of WhatsApp, which most Lebanese use to keep in contact with each other, given exorbitant calling rates. Incensed, demonstrators took to the streets, demanding the government step down. Others opted to leave. By the end of 2019, annual emigration had soared by 42 percent.

Little wonder, then, that Bassem and the other men he met that day felt leaving was their only option. They decided to sell cars, jewelry, and anything else that still had value and to pool their money and buy a $20,000 wooden boat. They would sail for six days and reach Italy, then cross on foot into Germany, where they would build new lives and dream new dreams. But the waters were treacherous, and the wild waves posed a risk.

The men insisted Bassem steer the trip through. He was a man of the sea. He could even guide a ship without a GPS; he relied on the sun and stars for guidance, they reasoned. He agreed.

With that decision, Bassem became another footnote in Lebanon’s long history of exoduses, stretching back well before the state’s independence in 1943. The Christians of Mount Lebanon in the 1880s kicked off multiple waves of emigration, spurred by a conflict with Ottoman Syria. From 1899 to 1910, about 90,000 immigrants departed Mount Lebanon to find work in the US. Others fled conflicts that have plagued the country’s (short) modern history. The Lebanese Civil War, from 1975 to 1990, pushed as many as 900,000 people out of Lebanon; most resettled in sub-Saharan Africa, Latin America, Europe, and the US. In the 2000s, Lebanese youths emigrated in droves to the Gulf states, attracted by the oil and real estate boom.

My family, too, were footnotes in successive Lebanese exoduses. My grandfather, an orphan seeking work, emigrated to Palestine in 1918. He became a prosperous ful seller and lived in Haifa until he was forced to return to Lebanon in 1948 during the first Palestine-Israel conflict, which prompted another Palestinian exodus known as the Nakba. My father would also leave his country. A newly graduated doctor dragged into the civil war, as were many young men at the time, he witnessed a brutality that scarred him. The Hippocratic Oath meant nothing during urban combat, and the sounds of gunfire haunted him for decades, even when he was far from Lebanon. In 1980, newly married to my mother, he sought the same economic opportunity and stability his father had and moved to the United Kingdom, where I was born. The plan was always to return. But following the 1982 Israeli invasion, my parents prolonged their stay to ensure their growing family’s safety. And so, one year became five, then ten, then fifteen.

While we were growing up, my deeply depressed mother played Lebanese music, especially Fairouz, for me and my siblings. When selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors lifted her mood, we sometimes caught her belly-dancing. She filled diary upon diary with thoughts of someday returning home, and the difficulties of living in a foreign land. The weather and the people were often too harsh for her to bear, she wrote.

Mama regularly cooked Lebanese ambrosia for us, including stuffed vine leaves, shawarma, and kibbe; the kitchen often filled with the aroma of freshly baked pita. At dinner, she shared stories about our grandparents, about the sun-filled promenade and the shimmering sea in her hometown of Sidon. The tales transported us to another land, to our homeland, which was far from gloomy Leeds in the UK, and filled with warmth, treasures, and light. We, too, felt homesick—for a place we had never visited.

Following the end of the civil war, many Lebanese, including my family, returned. Coming of age in Beirut made magic feel within reach. I spent my days reading Mahmoud Darwish’s poetry and listening to the leftist music of Marcel Khalife. My secret place was a small shisha cafe that jutted off the coast, tucked behind a five-star hotel, where I could smell the sea at sunset. I strolled along hidden streets dotted with orange-blossom trees, where I had my first kiss. I became an activist and advocated for civil marriage and against sectarianism. I joined friends in public squares to demand freedom from corruption and foreign interference; I cursed politicians with taxi drivers.

The political instability, power cuts, and mountains of garbage were intolerable yet somehow tolerable back then. Crumbling infrastructure interspersed with newly built high-rises illustrated the existential tension that tugs at the heart of Lebanon: the good and the bad, the past and the future, the wealthy and the destitute. I sometimes thought of that tension as a small price to pay to feel alive in ways that were inconceivable in the Western countries I eventually moved back to.

For my parents, the guilt of living in the diaspora had been daunting. And yet, as I would learn too, Lebanon was never without problems.

In 2019, the Lebanese economy collapsed and the protests calling for a new government swelled. I was in London, but I felt an obligation to be on the ground. So I took time off work, flew back to Beirut, and headed to Martyr’s Square the following evening with my mother. The determination was electric. The protesters chanted “killon yaa’ni killon,” or “everyone means everyone,” and called for widespread resignations. The solidarity among demonstrators spilled into song and dance. Food, coffee, and shisha flowed for all. Patriotic ballads and the clinking of coffee cups, pots, and pans floated in the fall air.

Despite their profound grievances, the protesters’ positive energy seemed boundless. I held Mama’s hand as we marched along. Teenagers clapped for her, and she clapped back joyously. “I’m hopeful the revolution will succeed,” she posted on Facebook. “I dream of a Lebanon where my children can come home and contribute to their own country.”

The hope that fueled the revolution for months eventually fizzled out. Although Prime Minister Saad Hariri resigned, politicians who already enjoyed impunity remained, as did the sectarian structures that buoyed them. But Hariri’s replacement failed to placate demonstrators. By 2020, black-market transactions were commonplace. Familiar corner shops shuttered; bakers went on strike; food prices soared. The crisis touched every community, every corner of society.

In the absence of a bailout, the meltdown worsened, and then COVID-19 struck, and with it, lockdowns and exponential economic devastation. The national currency’s value fell by 80 percent. Even the wealthy and middle-class could not access their cash: withdrawals were capped, and banks were boarded up. In July, a man shot himself in a busy neighborhood, leaving behind a note suggesting he was motivated by hunger. By September, more than 50 percent of the population had fallen into poverty. Mental-illness medication vanished from pharmacy shelves. Anger crested into rage.

My parents spoke of frequent electricity blackouts; private generators often ran out of fuel, and warm water was no longer a guarantee. As the cost of meat rose, Mama experimented with vegetarianism. The internet connection grew worse and yet more expensive; video calls offered pixelated faces of a weary nation.

Meanwhile, Baba said that the Syrian and Palestinian refugees who visited his clinic spoke of severe hunger and hoped for financial assistance from him. “I have never seen people this desperate for help,” he told me. Migrant workers who hadn’t been paid their wages, with no way to get to their home countries, were abandoned by their employers and ended up sleeping on the bare ground in front of their consulates.

And then, the blast.

In the weeks that followed the explosion, fears of a renewed exodus made the rounds on social media, deepening the uncertainties that had gripped the nation. For nearly all Lebanese, home had become “a state that is killing them slowly, and they are not just killing them with these explosions,” as Nadim Houry, a political researcher, told NPR. “What we’re talking about is really a fight as to who is going to stay in Lebanon. It’s they or us at this stage.”

Distraught mothers with furrowed brows made tearful television appearances lamenting their children’s forced migration. Beirutis listed beds and couches on Facebook Marketplace, with captions declaring they were fleeing. More than a thousand Lebanese Armenians, a community woven into Lebanon’s social fabric for decades, fled to Armenia, whose government promised returnees an aid package. So many of Lebanon’s highly skilled workforce, including nurses and engineers, left the country that the World Bank warned that Lebanon was facing a “dangerous depletion of resources, including human capital.” In a single year, the country lost 500 registered medics.

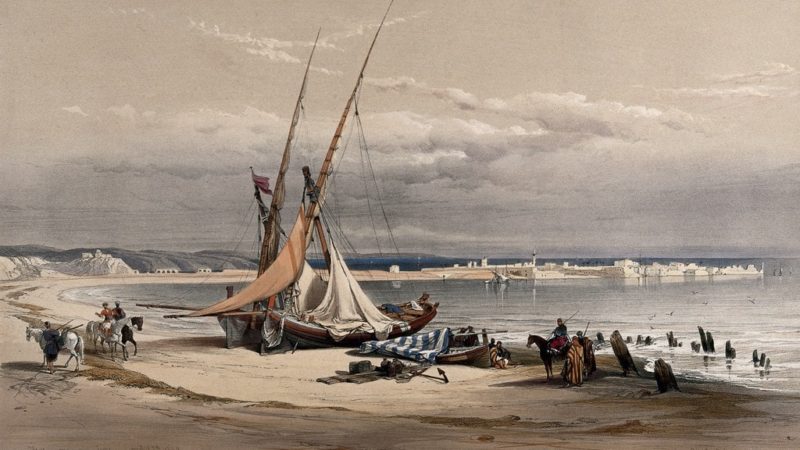

In September, hundreds like Bassem took to the Mediterranean Sea to flee, in scenes reminiscent of the Syrian refugee crisis. The families boarded flimsy dinghy boats from North Lebanon to make the dangerous crossing to Cyprus. Two children died at sea; their relatives had to push their tiny bodies overboard.

Bassem’s story awoke within me a profound guilt. He wasn’t just seeking stability, prosperity, and essential services, such as 24-hour electricity. He was also seeking basic dignity and the right to dream. His departure was not one of convenience with a second passport to rely on or financial cushion; it was one of desperation.

Conversely, when I departed Lebanon in 2008 for graduate school in New York City—although it was with a heavy heart—I always knew that I could come and go as I wished, or never return if I wanted. I would never feel stateless because I would always have my British passport. I felt guilty then, too: The 2006 war with Israel had wrecked the nation, and sectarian divisions intensified as Hezbollah tightened its grip on the levers of the country. I felt complicit in Lebanon’s disintegration and its brain drain; I had seized the power of a second passport to abandon it.

As I bade farewell to my parents at the Beirut airport, I wept. On the plane, I clutched a Qur’an Mama gifted me, even though I was hardly religious. “May Allah bless you bountifully,” she would say tearfully, when I’d call home from abroad. I’d promise I would return when “the situation” eased. I just needed time away to establish myself, to send money back home.

I knew I was fortunate to have these opportunities. But I still yearned for my motherland and my mother. I regularly read her journals, which she had gifted to me when I departed Lebanon, telling myself that she had had it far worse than I ever would. But I, too, daydreamed about Sunday lunches at my grandparents’ orchard. I longed for wafts of jasmine and honeysuckle, and glimpses of the old city gates, veranda shutters, and mosaic tiles. Trapped between languages, I reminded myself to think in Arabic. Just one more year, I told myself.

But one year became five, then ten, then fifteen. My grandparents died, one after the other. My parents’ health deteriorated; Mama’s knees gave way to osteoarthritis, as if the country’s burdens were on her shoulders. Baba, once invincible, started forgetting things. During his night terrors, he’d scream at invisible snipers and point at invisible tanks. The number of friends I visited during trips back to Lebanon waned, as they, too, were leaving.

By my thirties, the nostalgia evaporated, and my eyes stopped welling up. As I watched the unraveling of Lebanon from abroad, and with the benefit of time and distance, I could see clearly the flaws of my homeland. I began to feel lucky that I did not live there, even as my heart ached with guilt and resentment and sadness for feeling that way. “I will return at some point to make a difference, to contribute, to help rebuild,” I hummed under my breath.

Then the explosion happened.

It was 4 p.m. London time on August 4, 2020, when a friend sent me a WhatsApp video of the warehouse fire that would set off one of the world’s biggest nonnuclear blasts. I was mid-errand, standing in a socially-distanced queue at Whole Foods, buying groceries and preparing for an imminent trip back to Lebanon as I stared at my phone.

I rushed out of the store, not knowing what I was looking at; the plumes of smoke gave little away. Twitter was soon inundated with footage of the explosion itself: a pink-orange mushroom cloud, followed by a boom and harrowing screams. One after the other, we called our loved ones. Where are you? Are you okay? How much damage did you suffer? My parents were, thankfully, 44 kilometers away and safe, and yet felt the blast’s tremors.

The fear that I felt in that moment was all-consuming and dizzying as I steadied myself on a bench in North London’s leafy Camden, surrounded by families enjoying the solitude of COVID-19 lockdown measures. I sat in silence for some time, my mind struggling with the severity of the news, even as my body reeled from it.

I took the long route home, along Regent’s Canal, which usually brought me comfort. But on that day, Lebanon whirled in my mind. Fear made way for guilt, the guilt that I was not with my parents—my people—in that agonizing moment. Adrift in my thoughts, I failed to make way for a cyclist, whose shout startled me. The groceries I’d bought fell to the ground, and a single green apple rolled into the canal.

Seventeen hours into the Lady Maria’s journey, a storm cloud began to form and the wind grew stronger. The sea had lost its charming blue tint and appeared ominous and gray. The waves rose as high as six meters, enough for Bassem to taste the saltwater; the boat began swinging, and its passengers began praying. As the last strip of daylight faded, Bassem tried to keep his calm, but he was anxious and exhausted; he hadn’t slept in forty-eight hours. The winds were so strong that one traveler became severely dizzy, causing Bassem to worry more. “I turned to Allah,” Bassem told me. “I was terrified.”

He gripped his UHF radio to make contact with a nearby ship, which advised him to approach Cyprus for safety. The forecast was grim, and the Lady Maria was not sturdy enough to survive the fury of an impending storm.

Panicking, Bassem sped toward Cyprus at 45 miles per hour. It took five hours, which felt like ten, to reach the outskirts of the island. There, the Lady Maria was intercepted by the Cypriot police, who encircled the boat for thirteen hours before allowing it to dock.

The passengers were told to disembark and taken to a holding area, where they were tested for COVID-19. Bassem curled up on the ground and drifted into a three-hour-long slumber. When he woke, he collected himself and begged the authorities to let them continue their trip. Realizing they would not relent, Bassem’s chest tightened with bitterness. He knew what was to come: they would be returning to Lebanon the same way they had come.

Bassem watched with a tedious familiarity as the Cypriot shore disappeared. “I felt bitter,” he said. “I did not regret my decision to flee Lebanon, but a profound feeling of sadness came over me. I could not believe this was happening to us, after everything we had been through.” Soon after their new ship departed—they were forced to leave the Lady Maria behind—a desperate couple threw themselves overboard and swam towards Larnaca, Cyprus. It took the authorities thirty minutes to rescue them. “It’s like they were trying to make an example of them, to ensure no one else would try to do the same,” Bassem told me.

Enraged, he punched one of the policemen on the ship. A bigger fight involving eight men ensued, but Bassem was ultimately restrained. As he fell asleep later that night, he couldn’t tell whether his chest ached from the scuffle or the realization that his great escape had failed.

By Sunday morning, three and a half days after they had left Lebanon, the travelers were met by Lebanese soldiers and Internal Security at the destroyed Beirut Port. They were reprimanded and driven to a village in the mountains, where they were quarantined for fifteen days. “We returned to our humiliation and our poverty,” Bassem said.

I found myself walking Beirut’s streets four days after the explosion. It took me a moment to realize that the countless glittering smithereens, shining on the ground in the evening sun, were shards of glass that were once whole. They had made up the windows of homes, stores, schools, bookshops, cafes, hotels, churches, mosques, and hospitals.

I made my way to Karantina, the impoverished neighborhood adjacent to the explosion site, for the first time ever. The story of Karantina is intertwined with the port itself. It is named for its job: a place where travelers quarantined to curb the spread of diseases during the 1800s. It has historically endured numerous tragedies, including a massacre during the civil war, frequent floods, and now an explosion.

The blast decimated Karantina, yet there were fewer aid workers tending to the wounded there than in surrounding affluent neighborhoods, some of which had sustained less damage. Though the people I met in Karantina had little left, they welcomed me into their destroyed homes; they wanted nothing but to be heard. They spoke with tears in their eyes and fire in their throats.

Ahmad Hajj Steify, a Syrian refugee, watched his home collapse on his wife and daughters. His family fled the Syrian Civil War in 2014, hoping to start anew in Lebanon, only to be met with a crushing death. In the moments after the blast, Pascale Safadi, a Lebanese woman, was trapped between protecting her injured son and reaching her injured daughter. “Can we move to a country that loves children?” her traumatized four-year-old son asked her.

Karantina’s survivors faced the ever-present Lebanese dilemma: to leave or to stay? Despair was at the heart of that quandary. Some said they would flee if they could. But for personal or logistical reasons, most resigned themselves to the idea of remaining.

No more intense was that discussion than with Mariam and Desiree Darouni, a mother and daughter who lost their home and were gravely injured in the blast. Mariam, 64, lived through multiple wars, survived breast cancer, and experienced poverty. But it was the explosion that defeated her spirit, she said. She spoke of raising her daughters with regret for having brought them into this world, this country. “I wish I never got married,” she said. “I was worried that if I had children, they’d live in misery. Look at what’s happened!” Mariam grabbed my arm and implored me to leave Lebanon with my mother. “Listen to a woman who’s suffered from deep pain,” she said. “Leave.”

Meanwhile, Desiree, the family’s sole breadwinner with a monthly salary of $120, was adamant about staying. “I adore every street of Karantina,” the 30-year-old said. “I used to play tic-tac-toe outside, in front of what used to be our home. I want to settle here.”

The more time I spent in Karantina, the more I struggled to be away from it. My time there heightened the feeling that I belonged to this tortured, gorgeous country in a way that I would never belong elsewhere.

When I discussed my reporting with Mama that evening, I blamed the government for keeping us—hundreds of thousands of families—apart. I floated the idea of canceling my plans of relocating to New York from London and instead moving home—not in one year, or five, or ten, but now, to make a difference, to contribute, to help rebuild.

“Not now,” Mama said. “Maybe when the dust settles.”

But the dust never settles in Lebanon.

Following his return to Tripoli, Bassem spiraled into a deep depression. He stayed up all night, retracing his failed escape. The thought that he left with nothing and returned with nothing consumed him. Because of his attempt to migrate, the authorities had banned Bassem from the port, where he once spent his time fishing, his only real source of joy. “I felt like a heavy weight was sitting on my chest,” he told me. “I kept questioning how and why I was back at square one.”

In early October, Bassem spontaneously booked a one-way flight to Turkey. He had been in touch with friends who suggested he steer a ship from there to Italy. After brief deliberations, he decided he would take the risk, yet again, even though the details of the proposed journey were vague. If he failed, he would remain in Turkey and find a job there, he decided. Perhaps he would even remarry. When he mentioned the trip in his audio notes to me, his voice trembled. “I’m not sure who I can trust,” he said. “I’ll be traveling with strangers.”

I lost touch with Bassem the day after he was scheduled to set sail, once again, for Italy.

I thought of him when a Lebanese judge charged acting Prime Minister Hassan Diab and three former ministers with negligence over the explosion, and again, weeks later, when anti-government protests in Tripoli turned violent, leaving one young man dead. I was curious as to what he thought of the developments. But my WhatsApp messages to him have remained unsent, a single tick suggesting an unfinished story.

Before Bassem fled Lebanon for the second time in a month, he attended the first commemoration of the October revolution. When we last spoke, after he arrived in Turkey, I asked if he had any hope in Lebanon. “Maybe in its people,” he said, “not in the country.”

“Why did you attend the protests, then?” I asked.

“To stand in solidarity with those I am leaving behind,” he said. “I will never, ever forget them.”