My sister was on her way to work when she first saw it: heavy smoke above Paradise, where our parents live. She grabbed her phone and dialed them. No answer. It was early, not yet 8 a.m. They were still asleep.

She called again. On the third try, my dad finally picked up. The sky had grown darker. There was no time to explain. “Go outside and look,” was all she said.

The first I hear of it is late in the afternoon. I’m at work in Times Square when my sister texts me, “Mom just got back to me. They’re still stuck in gridlock. Their house is probably gone.”

At first, I don’t know what she’s talking about, but then I remember: even though it’s November, it’s still wildfire season. Since my parents and little sister moved to Paradise fifteen years ago, they’ve had to evacuate multiple times. My mom keeps boxes next to the front door labeled FIRE for things like the checkbook and my grandma’s tortilla recipes. Keepsakes are permanently stored in a hauler by the road, ready to be hitched.

As for me, I live in New York and have the luxury of forgetting about such things. I call my sister back while panic-Googling “California wildfire news.”

I learn its name just as she picks up.

“Camp Fire,” I say.

“More like hellfire,” she answers. “I made it out, I think, but Mom and Dad are still in it. If they make it, I booked them a motel in Marysville.”

My heart froze as two scenarios flitted by: one, my parents in a Motel 6 tonight; two, my parents both dead.

I try to collect my thoughts while she continues. She tells me how, when she arrived for her shift at the dental office, her coworkers didn’t think the fire was a big deal. Ash was falling from the sky, but there was no notice to evacuate. Just another brushfire in the woods, they figured. Still, they decided to close up for the day. She and the other hygienists stayed and called their patients to cancel. My sister only left when she saw something she never imagined—that the Safeway across the street had caught fire.

Outside, she faced a long line just to get out of the office parking lot. Traffic on Skyway, the only road for the mountain villages above Paradise, was at a standstill. Spot fires lined the edge of the street. By the time my sister finally pushed her way onto Skyway, fifteen minutes had passed. That’s when she realized she had only a sliver of gas left.

As she tells me this, I almost drop the phone. She needed gas? Growing up with parents like ours, being unprepared—not having gas in the tank—is unthinkable. A violation of rule number one. I don’t say so, lest she burst into tears. I just hold my breath as she tells me how she turned off Skyway and onto a side street knowing full well that she might not get back on. How the fire around the Valero gas station looked ready to blow the whole place up. How the least dramatic scenario of her death was that the flames would simply overtake her at the pump.

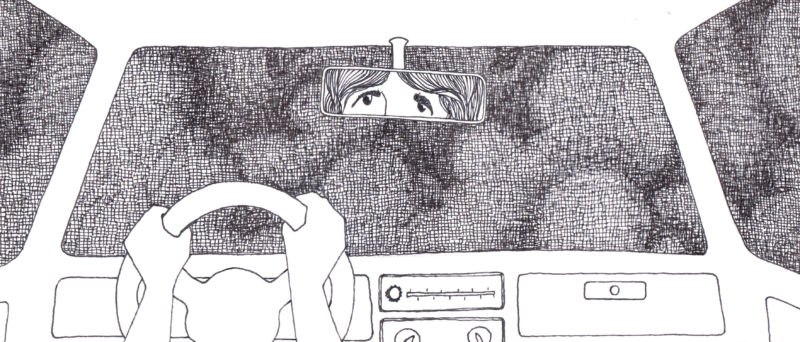

Instead, while she was pumping gas, the onslaught of cars on Skyway suddenly paused. The police were directing cars on her side street back in. She ditched the pump, got back in the driver’s seat, and sped to the corner to make it. She wasn’t out of the woods yet—the woods were still on fire. Cars sat in gridlock, occupying every inch of blacktop. The smoke made it nearly impossible to see. She inched down Skyway, terrified. It took an hour for her to reach the edge of the blaze. On the other side was an inconceivable blue sky.

Though right now she is very much alive, I feel that I just glimpsed her death.

I want to call my mom next, but I don’t want to press my luck. One family member managed to escape; it feels dangerous to ask for more. Plus, she might be driving. She’s the doting kind of mother who might pick up the phone, see it’s her daughter, and get in a wreck trying to answer. In the flawed logic of disaster, I don’t want my call to put her in further peril, so I send her a text instead. No answer. I’m still sitting at my desk, phone in hand, when I realize I don’t know what I’m doing. Not just right now, but in the larger sense. It’s like I’ve been on autopilot all this time. My whole adult life, I never gave a thought to the fact that I live far from my parents. It was normal, fully rationalized. And yet, this morning, my sister’s proximity to them very likely saved their lives. It makes me wonder what might have happened if I had been there for them, too. Maybe I’d have up and moved them someplace else by now, somewhere not under constant threat. The fire would still come, the land would still burn—it always has, and it has every right to. There’d just be one less family in its way.

I’m thinking it’s hard to believe that I spoke with my mom just yesterday. We had talked about how unseasonably hot it was there. About how they were busy converting the garage so we could stay over at Thanksgiving. And how they’d upgraded “the palapa,” the corrugated metal patio on their mobile home that I once jokingly named after those beach huts in Baja. My dad had started putting boat netting and nautical tchotchkes all over so it would kind of feel like a palapa, even though they’d never seen one before. And now maybe they never will…

I can already see the wall of guilt and regret I’ll have to face if they don’t make it out. A darkness like I’ve never seen, awaiting me on the other side. I close all my Camp Fire browser tabs and stuff my computer in my handbag. This day has been long enough.

Hurtling into darkness, on the train home I read the news of the first reported deaths. Five found on Edgewood Lane, immolated in their cars. I know Edgewood Lane. It’s the only street that connects to my parents’ dirt road.

At 8 p.m., I get a call. When I see her name come up on my phone, I realize I’ve been holding my breath. A beautiful woman of sixty beams back at me, dark curls held up by a sun visor. It’s my mom.

Before she even speaks, I can hear the TV news blaring in the background and my dad, per usual, talking over it. Motel 6. They made it.

She tells me she and my dad had taken separate vehicles. Otherwise, they left everything behind. Birth certificates. My grandparents’ wedding photos, the names of every long lost tía and tío written on the back. They even left behind their pet, a ditzy parrot named Bucket. Bucket had come to them sixteen years ago and six hundred miles south, in the house I’d grown up in. One day, a bunch of parrots appeared out of the blue, squawking and flashing their colors at the suburban crows. My dad came out to inspect. He stuck a finger out like a perch, and one of them swooped down. It clamped on with no intention of leaving, so my dad took it in and gave it a cage. We named him Bucket, after the clucking sound he made when dancing on his wooden dowel. But usually we just called him “The Bird.” When my family relocated, he grew into his role as the family pet: the Bird of Paradise.

But this time, when they left, they didn’t have a minute to spare. One of their neighbors, a family, had already fled, their truck and trailer gone. The fire had become visible—the glow of it and the dark smoke it gave off were cresting the hill at the top of their road. Yet, everyone else’s cars were still parked there in the dirt—not a good sign. Across the way, a guy was banging on the door and bellowing, trying to wake the family inside. The only other neighbor was the old woman next door. My mom ran to the woman’s house, calling out.

When, later, the names of the dead were released, I learned about the neighbors. The old woman next door, the family across the street, even the family that left early in their truck—none of them survived.

When I saw the sheriff’s photos, the only things I could identify were a stone birdbath, and the hauler, now just a charred frame. Across the way were the neighbors’ cars, burnt down to the metal. Everything else had been reduced to ash.

I have always told my mom she could call me to talk, even if it’s late. She has never taken me up on it. But the same night I learned she’d made it through the fire, at 2:30 a.m., the phone rings.

In a quiet voice over my dad’s snoring, she tells me the following:

When we left the house this morning, the sky was amber. A minute later when we turned onto Edgewood, it was black. Pine trees were going up like torches, burning from the bottom up. Everything was exploding. Cars. Propane tanks. We gunned it out of there. The houses—you could see the flames behind them. Before you even passed, they lit up, totally engulfed in fire. Already, there were abandoned cars. Cars on fire. I thought that was going to be us, it came on that strong. Then up ahead was this wall of black. You couldn’t see through it. I watched as your dad pulled into the oncoming lane, speeding toward it. He never speeds. He was going faster, and I thought, Oh God, here we go. I followed him, and right before we reached it, he slowed down.

Heavy smoke is just as deadly as fire. I need you to know this, in case it ever happens to you. If fire or dark plumes of smoke are blowing across the road in front of you, and it’s your only way out, you have to go through it. Don’t accelerate when you’re in it. You need oxygen to breathe, and so does a combustion engine. If you find out the fire and smoke go on more than a couple yards, your car might stall. You can’t let your car stall out in the middle of that blackness. There’s no air. Don’t try and run then—you won’t make it.

So, listen. What you need to do if there’s a wall of flames or smoke up ahead, and the road is straight, get your speed up. Forty or fifty miles an hour—the faster the better—and just as you’re about to enter, take your foot off the gas. You won’t know how far away the other side is. You’re just flying through it. You’re driving blind. But don’t be afraid. If you coast, you’ll punch through the darkness.