It’s early April of 2020 and I’m in my in-laws’ garage—a week after my partner and I spontaneously downloaded hours of children’s shows for our then three-year-old, packed up the Honda, and fled pandemic Brooklyn for the relative safety (and childcare) of rural Minnesota. My hair is gathered in a ponytail atop my head, the sides that I usually keep in a fade have grown out so that my grays show. There’s a Harley up on a motorcycle lift behind me and an illuminated Jack Daniel’s sign beside it. My partner holds the buzzer up inches from my face and I eye it with a nervous smile. My father-in-law has his phone out to video, and jokes that this is the kind of thing people will come up with in isolation. I smack my gum, shifting on the cool plastic of the barstool beneath me. And then I feel the cold teeth of the buzzer vibrate from my widow’s peak to the back of my head. “I want it to come off in clean pieces,” I say, before my partner drops a clump of brown hair in my lap. “Whoa,” I exclaim, laughing, “No going back now.” Adrenaline shoots through me. I feel more alive, more present in my own body than I have in a long time. The years of fearing how people perceive me, and in particular my gender, seem to slip away.

When I first read Leslie Feinberg’s 1993 novel Stone Butch Blues, I was a first-year college student in a queer reading independent study I had devised with some friends, one of whom I hoped to date. I was a young eighteen, though I considered myself mature and cultured, mostly because I was from Manhattan. In fact, I had zero experience doing adult things like cooking, laundry, having a job, and writing a check, and was still trying to convince myself I was bisexual even though I was obviously gay. I was involved in a lot of pretending, and was coming to realize that not everyone grew up wealthy—and that I had. At the time, Stone Butch Blues was talked about through the queer grapevine as a book I had to read; it was part of both the lesbian and trans canons. Before I reread the book a year ago, I hadn’t remembered much about it beyond some blurry butch/femme bar scenes, and that it felt like important queer history. I’d existed so far away from the world of the book—the factories, working class bars, police beatings and rapes, and all the butch bravado that surviving it entailed; I still do. But, along with my youthful inability to fully digest a world unlike my own, I see now that, at eighteen, it must have been hard to look honestly at the word “butch” for fear of recognizing myself there.

Stone Butch Blues tells the heartbreaking story of Jess Goldberg, a fictionalized version of Leslie Feinberg. Growing up white and working class in Buffalo in the 1950s and ’60s, Jess is bullied by other kids; adults make her feel different and wrong, and she is questioned about her gender at every turn. The refrain she hears throughout her childhood is, “Is that a boy or a girl?” Jess also comes from “the only Jewish family in the projects,” who in turn represent one of the only working-class families at their synagogue. “The world judged me harshly and so I moved, or was pushed, toward solitude,” Jess thinks. At fifteen, she gets an after-school job at a printing press, and from a coworker learns about a local gay bar, Tifka’s. When she finally summons the courage to go there a year later, she finds solace and community, and her butch education begins.

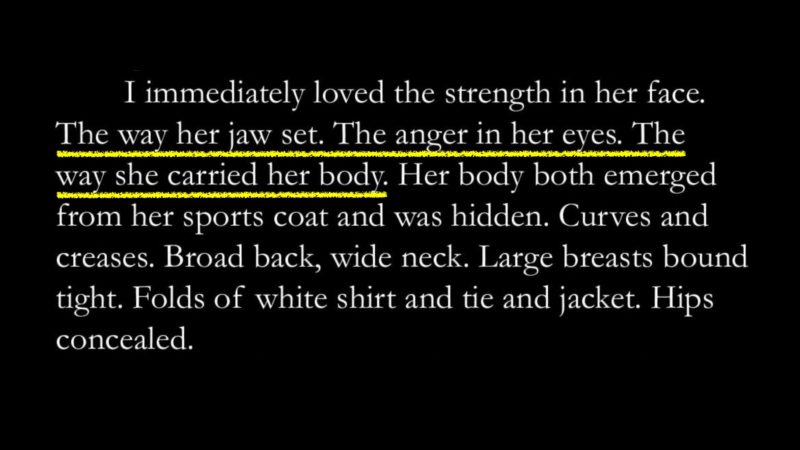

Jess discovers a world where butches wear suits in bars (and, she later learns, white t-shirts on the assembly line), where they slap each other on the back and slow dance with femmes. A butch/femme couple she meets, Butch Al and Jacqueline, become her mentors; they help her buy her first sports jacket and tie, explain butch/femme sex to her, and even cut her hair. It is by watching their relationship that Jess learns “what I wanted from another woman.” Jess can’t pass as anything other than in-between (she is no “Saturday-night butch”), which is what draws friends and lovers to her and seems to repulse everyone else. And so, Jess rides a motorcycle and emulates the tough veneer of Butch Al and her other butch mentors, while learning to live with the daily disgust and dehumanization she faces for being a “he-she.” The lives of butches are radically limited: by the kinds of jobs they are allowed to hold (mostly in bars and factories), the places they can go, when or where it might be safe to go to the bathroom, and their ability to get medical care.

The world of these butch women is both beautiful and claustrophobic. Congregating at Tifka’s, at house parties and work picnics, they are a tight-knit circle bound by empathy, pride, and shared pain. When Jess and her friend Ed are brutally beaten by police outside a Black gay bar—targeted both because they are butch, and because Ed is Black and Jess is white and thus a “fuckin’ traitor” in the cops’ eyes—Jess is too injured to work, and loses her job. To raise her spirits, her drag queen friends get the cash together to buy her a new suit, and encourage her to be the emcee of their drag show. The butches and other queers create community, often (though not exclusively) in the aftermath of trauma, and their moments of shared joy are all the sweeter because of the physical and emotional violence they endure. This community also extends to queer sex workers, who too face job insecurity, police violence, social stigmatization, beatings, and rapes. The butches and sex workers date and hang out in bars and diners in the early hours of the morning after “the working girls” get off. Milli, a sex worker who is Jess’s girlfriend early in the novel, tells her “pros” and stone butches “just fit”: Butches, she says, are “the only women in the world who hurt almost the same way I do.”

At the same time, in Stone Butch Blues, butch is the norm and a validated, if marginalized, category of its own. Lines like “You’re a real butch” or “Get the butches together” pass breezily. At Jess’s factory jobs, “[i]t meant a lot to have another butch watch your back.” Though Jess and her friends face constant discrimination from coworkers and bosses, they try to protect each other, even as their gender in-betweenness makes job security extra precarious: “With union protection, all the butches agreed, a he-she could carve out a niche, and begin earning valuable seniority.” Feinberg uses the subject of factory work and labor organizing to solidify the butches as their own faction, while also opening up the world of the book as they organize and live in community across race and gender. At one of Jess’s first factory jobs, she is the only butch but is embraced by a group of Native women, though a foreman tries to break up these friendships and keep the workers divided. In a later job, Jess becomes the first woman promoted to “Grade Five,” only to learn that her advancement was just a ploy for the racist foreman to avoid giving an overdue promotion to Leroy, a Black employee. In an act of solidarity, Jess refuses the promotion, much to the dismay of some of her butch coworkers. Leroy ends up getting the deserved promotion, and later stands up for Jess when the foreman sexually harasses her. When a fight erupts between Jess and the foreman on the factory floor, she is less isolated because her community has expanded to include Leroy and the other workers who side with her.

In the aughts, when I was in college and a few years after, “butch” was out of vogue, often deployed teasingly or used as the butt of a joke. No one I knew identified as butch (or nonbinary for that matter), not even the women who were masculine-presenting. And “butch/femme” was a linguistic anachronism, despite the fact that plenty of women identified as “femme” and it was even cool to do so. When I realized that I didn’t want to, and couldn’t, pull off femme—and thus appear what I thought of at the time as “normal”—I preferred androgyny and the idealization of thinness that came with it. Looking at pictures of myself in college, I can see my style change: from wearing tight pants and a skirt (a signature look of my late teens that I now seem to share with my four-year-old) to always wearing pants with a tight shirt, to the suits, bound breasts, and loose-fitting shirts of my senior year. And my hair got shorter. My gender expression didn’t follow an entirely linear arc, but there was a clear progression. For a long time, I avoided presenting as masculine as I wanted to for fear of looking butch and embodying the shame I imagined would come with it—even though I knew it would make me feel more comfortable in my own skin.

Today, there is considerably more space to be in-between or gender non-conforming than there was in the ’60s and ’70s, when much of Stone Butch Blues takes place; more too than in 1993, the year the book was published, or even as recently as five years ago. In fact, Feinberg was writing about what it meant to be nonbinary before it was a recognized term or identity in the white Western world (though it has existed throughout time, and of course is more or less accepted depending on a person’s location and identity markers). While binaries (cis/trans man, cis/trans woman) were very much the norm when I was finding my way in the queer world, more and more people are now identifying as nonbinary, and/or as they/them—and seem to be finding acceptance, or at least acknowledgement. There is also more recognition of a continuum between gender non-conforming and trans, acknowledging a connection between those of us who live outside gender norms and those who identify as trans, and/or who medically transition.

As I read and reread Stone Butch Blues, I wish Jess could know how beautiful she is, and that I could transport her to a time and place where her in-betweenness could be better appreciated. I want to tell my younger self how beautiful she was, too: that my short, styled hair, sports bra-bound chest, and men’s clothing needn’t have been a costume I only wore in the queer world. That I didn’t need to put on a skirt to go out to dinner with my grandfather when I was in college, or try to look less masculine when I traveled home from San Francisco in my early twenties. (This attempted butch obfuscation wasn’t working anyway; when I wore a skirt I looked both awkward and miserable.) It took me years to stop the masquerade. But even then, I would have blanched if someone called me butch. In his iconic 1998 book Female Masculinity, theorist Jack Halberstam writes about encountering “butch-phobia” when trying to get drag performers to cop to their butch identity: “Even drag kings who wore drag on- and offstage and who had very boyish or mannish appearances would not identify as butch.”

There are a number of possible explanations for butch-phobia. For starters, butchness can be a tight container in which to hold an identity, as it implies not only a masculine appearance, but also toughness, coolness, and perhaps even emotional distance. The butch characters in Stone Butch Blues have difficulty expressing their feelings. To be “stone” in this book is often the result of being hurt, whether physically or emotionally, and implies being damaged. More perniciously, “butch” comes with the stereotype of mimicking male chauvinism and heteronormativity in general, as though butch/femme were some fledgling imitation of the straight world. In fact, butchness actually expands the parameters of who can embody masculinity, challenges the idea that masculinity is the natural domain of cis (or trans) men, and creates new forms of it. As Halberstam writes, “far from being an imitation of maleness, female masculinity actually affords us a glimpse of how masculinity is constructed as masculinity.” But aside from being perhaps overly singular and burdensome, some of us on the masculine-of-center side of things resist the “butch” label because we have internalized the world’s displeasure with butch bodies, and feel the shame of inhabiting a female body that society tells us is less than, or incomplete. There’s something so vulnerable, so exposed about a butch body.

When I was ten or eleven, I got out of the shower, wrapped a towel around my waist like I always did, and walked through the living room, where my parents and another couple were chatting. As they stared at me, I said, “What? I don’t have breasts yet.” The adults laughed uproariously and I felt a hot shame—or maybe it was fear. I had always been a tomboy, aggressive, with a deep voice; on the edge of puberty, I was walking a fine line. By high school I threw myself into the conventions of femininity, or at least tried. I bought Mudd jeans like the other girls, experimented with makeup, and wore tight shirts and tank tops with spaghetti straps even though I felt self-conscious about my breasts. Because if I had few examples of high femme women in my life (my mom dressed out of a Lands’ End catalogue), I had even fewer examples of tomboys who extended their tomboyishness into adulthood. If I was going to be gay, as I already knew I probably was, then I figured I should at least be feminine. There was also the fact of my privilege: Growing up, I had access to so much I didn’t want to lose, even unconsciously—nice restaurants, private school, family vacations to Europe and Puerto Rico, the assumption that I wasn’t shoplifting even if I was. Being anything like butch would have meant no longer being able to move seamlessly through a white, moneyed world, and instead announcing my difference and causing stares. It didn’t even feel like an option.

This is why I find the way Jess (and Feinberg) unabashedly claim their butch identity so inspiring—both nineteen years ago and today. The butches in Stone Butch Blues do not try to make themselves less butch or more normatively female. In fact, halfway through the novel, when Jess’s life becomes unlivable—it’s the early ’70s; factory work has dried up and police harassment in gay bars has escalated post-Stonewall—it is not appearing more feminine, but more masculine that presents itself as the best option. When Jess starts testosterone it’s not because she longs to be a man, but because she feels she can no longer live as a butch. “I don’t feel like a man trapped in a woman’s body,” Jess tells a butch buddy, before her transition. “I just feel trapped.” She presents her reasons for transition as survivalist; being visibly butch has become, and in some ways has always been, untenable.

Ultimately though, this is a nuanced, nonlinear transition story: Jess later stops taking testosterone and comes again to identify as she/her and butch. Instead of transition “fixing” Jess’s problems as she hopes it will, she experiences passing as a calmer but much lonelier existence, cut off from the butch and larger gay community. Feinberg shows us that trans and butch are not mutually exclusive nor a replication of a male/female binary; in fact, Feinberg herself identified as both transgender and butch. Shortly before Jess stops taking hormones, she examines her reflection in the bathroom mirror:

As much as I loved my beard as part of my body. I felt trapped behind it. What I saw reflected in the mirror was not a man, but I couldn’t recognize the he-she. My face no longer revealed the contrasts of my gender. I could see my passing self, but even I could no longer see the more complicated me beneath my surface.

It’s not simply that Jess either loves or hates this transitioned version of herself. Instead, she misses being visibly butch, and comes to see being in-between as a more authentic expression of her identity. Considering her earlier transition, Jess sees that she’d hoped to “express the part of myself that didn’t seem to be woman,” but now realizes she never got the chance to “explore being a he-she.” When she stops taking hormones, she’s left more in-between than ever and without the privileges of passing. Her deep, hormone-affected voice and a flat chest from top surgery remain, but she is otherwise recognizably female-bodied. Still, she sees top surgery as “a gift to myself” and a “coming home to my body.” In this way, Feinberg resists binary notions of gender—pre, post, and post-post transsexual—choosing instead to chart the beautiful, complicated middle.

For as long as I can remember, my breasts have felt like a hindrance and a vulnerability, something I’ve learned to hide away in sports bras or sometimes binders in order to feel attractive and safe. When I was a kid, there was a lot of speculation about whether I would end up with my grandmothers’ D+ rack or my mother’s barely noticeable As. Unfortunately for me I got the D+ inheritance. Once puberty hit, I hated the way men looked at, commented on, and touched my chest. When I moved out to San Francisco in my early twenties and met many trans men who had had top surgery, I was jealous. While taking testosterone had never appealed to me, even if I was curious, I envied the flatness underneath their shirts. Later, I met people who had taken testosterone or had top surgery—one but not the other—a decision that still awes me in its disregard of gender norms. To transform without the privileges of passing represents a commitment to looking how you want to look, to being visibly queer and existing outside a recognizable binary.

The real arc of Stone Butch Blues is about becoming comfortable in liminality and difference. In the book’s final section, Jess embarks on a new life in New York City and slowly builds a relationship with her neighbor Ruth, a trans woman who Jess describes as “different like me” and with “shades of gender in her voice…like mine.” The relationship is wonderfully unexpected, and here again, Feinberg complicates our understanding of Jess’s desires and identity, as the women Jess had dated or lusted after until this point had only been referred to as “women” (with cis as the default). Over dinner, Jess asks Ruth, “Did you think I was a man when you first met me?”

She nodded. “Yes. At first I thought you were a straight man. Then I thought you were gay. It’s been a shock for me to realize that even I make assumptions about sex and gender that aren’t true. I thought I was liberated from all that.”

I smiled. “I didn’t want you to think I was a man. I wanted you to see how much more complicated I am. I wanted you to like what you saw.”

Ruth brushed my cheek with her fingertips. I shivered. “Well, I didn’t understand right away, but I thought you were awfully cute and handsome and interesting-looking.”

The last few years before the pandemic had been a crawl toward self-acceptance for me, as a gender non-conforming person. While I’d left behind the “masquerade” of dressing differently for family than I did friends years ago, there had never been an aha moment where I fully jettisoned shame and the judgement of others. When I decided to wear a “men’s” suit to the love ceremony my partner and I had seven years ago, I felt like I was taking a leap, really going for it. Somehow, I still thought that there might have been a less butch path for myself on that day or any other. Although in retrospect, what else would I have worn?

Stone Butch Blues was published before there was ample language to describe what trans writer and activist Lou Sullivan has called people with “their own interpretation of happiness.” In his diaries, describing his life from age ten until his death from AIDS at thirty-nine, Sullivan struggles to define and then inhabit and assert his gender and sexuality; eventually he finds his way as a gay trans man at a time when those identities were thought to be paradoxical. Feinberg, lauded as a transcestor, died in 2014 at the age of sixty-five, and hir (Feinberg used the pronouns she/zie and her/hir) writing retains a vital place in the queer canon. Stone Butch Blues is still seen as a novel that breathed humanity into the lives of marginalized people and challenged gender and sexuality norms before its time. In a 2017 essay for Jewish Women’s Archive, genderqueer/nonbinary writer Jacob Klein writes that Stone Butch Blues “remains an essential text, radically reminding us of the variation and mutability within the LGBTQ populace.” Klein echoes my own experience, reflecting that “[i]n Jess’ drifting from the gender assigned to her, I saw a parallel with my own gender squirming away from what I’d expected.”

I hadn’t planned to shave my head before the pandemic struck and quarantine life took hold, even if it epitomized gender freedom to me. But as the structures around space and time collapsed, that shift allowed me to do what had previously felt impossible. My fears that I’d look too bald, too weird, too butch seemed to fall away. Embracing butch felt like a relief. Butch is not simply an alternate masculinity, but a reimagining of what it means to be liminally gendered, to exist between (or beyond) man and woman. There’s the history of “butch”—some of which is told in Stone Butch Blues—and then the unfolding present. “Butch” isn’t static but continues to twist and turn. It has a foot in current trans and nonbinary identities, at least at their most expansive. But then it’s still very specific, as when Jess walks into her first gay bar and cries upon seeing the “strong, burly women, wearing ties and suit coats” and thinks to herself: “They were the handsomest women I’d ever seen.”