After I read aloud from my second novel at the Miami Book Fair in November 2012, a journalist who had covered the book once before asked for a follow-up interview. “Would you mind if we don’t actually do this?” I asked quietly. “My mother died, and I got uterine cancer from my arthritis drugs, and now I’m having an autoimmune flare up in my eye and I can’t think of anything new to tell you about my book.”

“That’s just fine,” she said. “Really.” And she gave me a hug.

That December, when the Ohioana Library Association invited me to Columbus to talk about my book the following May, it seemed like the height of foolish optimism to accept. I couldn’t walk, I couldn’t eat out, and sometimes I couldn’t see. But accept I did, flattered, little knowing that this would be the only trip I would take between December and May.

During those months, the Midtown acupuncturists to whom I had begun commuting weekly via mobility scooter and subway recommended that I drink squishy plastic pouches of medicinal decoction and do a daily self-treatment called ” moxa.” Also known as mugwort, moxa is an herb that Chinese apothecaries sell in a roll that resembles a fat cigar or, as many passers-by came to remark over the following months, the world’s biggest joint. Western researchers have found that the smoke of burning mugwort (Artemisia Vulgaris) increases blood flow to the pelvic area, which for someone who had recently had a hysterectomy didn’t seem like a bad idea. Chinese medicine holds that moxa fights the cold and dampness that in their view causes arthritis. You don’t smoke the moxa cigar; you hold it near an acupuncture point to activate the flow of chi. The great thing about Chinese medicine is you don’t have to believe in it for it to work.

I was afraid to travel. Between the mobility scooter and the strict diet that kept the arthritis in check, it seemed like too much. I was sure something would go wrong. I would wind up stranded and hungry. I’d come home crippled with more pain. “You should cancel,” my partner Sharon recommended.

“But I gave my word,” I objected. “And the only way to find out if I can travel is to try.”

“Okay, have it your way. But I don’t want to come as your aide,” she said.

“That makes two of us,” I replied, remembering, with prickly embarrassment, the time my mother, then sixty-six, rented a wheelchair for me when I was thirty-six. “I’d rather travel alone.”

The night before I left for Ohio, I roasted a big batch of vegetables and portioned them into three days’ worth of Tupperware containers. I froze six pouches of Chinese herbal brew. I packed several cans of sardines, a hot plate, a sauté pan, and a wooden spoon. Almost as an afterthought, I packed my clothes. I packed my scooter charger and I printed out the TSA regulations governing mobility scooter batteries, in case anyone gave me a hard time at the airport.

The next day I propped the food suitcase on the frame of my scooter and wheeled my clothing suitcase beside me to the curb without a hitch. To my relief, the scooter folded neatly into the trunk of a cab with my suitcases. I glided through the airport to Security with ease, and neither scooter nor food suitcase raised any red flags with TSA. And then, just as I was rolling away from Security, I stopped rolling. The drive belt that connects the motor to the wheel was lying on the floor beside my motionless scooter, looking just like what it was: a broken belt.

Suddenly the scooter wasn’t helping me with my burdens; it was a burden, thirty-five pounds of dead weight on wheels. I hobbled as I rolled the scooter, workbag and food suitcase in tow, over to the gate. I gratefully accepted the offer of a wheelchair up the jetway, but not before calling the scooter company and asking them to FedEx another drive belt to my hotel in Columbus.

Now that the food suitcase and scooter-husk were safely stowed away, I could look forward to the trip. Columbus, Ohio had been my hometown until the age of eleven. I no longer had family in Ohio, but I had a lunch date planned with my elementary-school librarian, Marilyn Parker. The Ohioana Library Association had given me awards on two previous occasions, and I had become friendly with the staff over the years. I had first learned to walk in Columbus. What better place to try traveling again?

I would have one evening to myself after the author events ended late the following afternoon. If my drive belt arrived in time, I could take a cab to German Village, my first neighborhood: red brick and sycamore, alleys and cobblestones, hitching posts with horses’ heads. I could scoot through Schiller Park, where I once learned how to sled, swing, slide. I could roll up to the Book Loft or to my old library on Parsons Avenue. I could poke my nose into my childhood backyard.

My happiest memories of my mother, now dead just over a year, had been formed in a red brick house on Ebner Street, where we lived until I was nine. I remember the time we spotted a black-and-gold bird among the feathery cosmos flowers my mother had planted. Dangling from the stem, the bird’s weight pulled the purple flower almost to the ground. We watched together, so close I could smell my mother’s cigarettes, the tuberose in her perfume. “Look,” she said. “It’s pecking out the seeds.” She opened her bird book and showed me how to match the living, darting animal to its printed image. Decades later, I can still recognize an American Goldfinch.

When the plane landed, my scooter lay waiting for me at the gate, no more and no less broken than before. I unfolded it and once again balanced my food suitcase on its frame. A thoughtful United employee offered me a wheelchair, pushing both me and my scooter through Baggage Claim to the curb, where Marilyn Parker met me in her car. When she heard about my broken scooter, Marilyn took me to Columbus Mobility Specialists, just in case they had the drive belt I needed. They didn’t. “But it was awfully sweet of you to take me here,” I said.

“My mother was in a power chair at the very end,” she explained. “I know this place like the back of my hand.”

When my mother had rented the wheelchair for me, she had been in so much pain from her own arthritis. I remembered the way she refused my help when she hauled the chair out of the trunk. I’d felt so much shame. In the prime of my life, I should have been carrying things for her, and for Marilyn too, now, for that matter. But I couldn’t. Like Marilyn, my mother had rented a chair for her own elderly mother, who lived to eighty-six. As Marilyn lifted my scooter out of the trunk for me, it was as if my mother were alive again, calling forth the same wash of shame.

After a brown-bag lunch in my hotel room with Marilyn followed by a reading at a community center, I fried up my dinner on the hot plate and brought it down to the hotel banquet room, where I ate it while chatting with other writers and the Ohioana Library staff and board members over their hearty catered spread. I floated politely above the envy I felt for their food and for the offhandedness with which they ate it.

After dinner, I took my moxa outside to burn. Not only does a moxa roll look like a cigar, it’s just as smoky, with a pungent odor somewhere between sage and marijuana. Heating an acupuncture point on each leg for three minutes each generates a lot of smoke.

It was drizzling outside. I crouched under the hotel overhang and lit up. A hotel employee came outside to ask what I was doing. “People were asking,” she explained. I told her a little about moxa, switched legs, and kept going, earning me another visit from the hotel staff a few minutes later. I’d lost my grip on Midwestern English: What are you doing? didn’t mean What are you doing? It meant Stop doing that. I trudged carefully inside, amazed that my feet seemed to be holding up with only moderate pain. “There’s a park next door where we like to smoke,” another hotel employee told me, pointing the way.

The next day, the organizers kindly placed me at an author table close to all three rooms where I was scheduled to speak, so I was able to pad from one to the next without too much pain. I tried to ignore the beguiling aroma of the Fritos that another author was eating, and tried not to feel mocked when he said the lunch I’d brought smelled good. How could he have known?

I took the author shuttle back to the hotel and was delighted to discover my drive belt waiting at the front desk. I would need a set of Allen wrenches, I discovered. I wasn’t hungry, but I snacked on an avocado to prepare for a reception at the Ohio Governor’s Mansion, where another banquet awaited a tent full of writers and patrons of the arts. Most people stood and ate; I sat and sipped a glass of water, chatting with my fellow sitters, the injured and elderly. I asked the Ohioana Library staff if they knew anyone from whom I could borrow an Allen wrench and they found the head of maintenance for the Ohio Governor’s Mansion. “I’m so sorry. The tools can’t actually leave the premises. If they were mine to lend, I‘d lend them to you, no questions asked,” he said gently. “Have you tried asking the maintenance staff at your hotel?”

I hadn’t. “Great idea!” I said. “Thank you!”

I became hungry. I can still remember the glistening egg rolls, the baklava, fragrant with honey, the chocolate-robed strawberries on skewers. I remember how the waiters sailed by, lofting silver trays of dainty toasts flecked with red caviar or glossy with melted cheese. Even if I couldn’t eat the food, it was humbling that there was a tent full of people who wanted to feed me, just for having written books.

At the hotel, one of the maintenance guys spent almost an hour fixing my scooter, and then refused the forty bucks I tried to give him. Still hungry, I found the park the smokers used, and burned my moxa in peace. Back upstairs in my room, I took out yet another plastic tub of roasted vegetables, only to find that it had frozen into a Tupperware-shaped block. I felt despair. It had been light outside when I’d left the party, and now it was almost ten at night as I softened my block of icy vegetables on the skillet, chiseling at it with my wooden spoon. I had been polite and friendly and well-spoken for two days. I had gamely minimized my limitations, and nothing bad had happened to me. Everyone had been so kind. But I was hungry and tired, and my food was a frozen lump.

By now, my childhood library, bookstore, and park were surely closed. Back when I hadn’t been eating so carefully, I might still have been able to get a sugar-covered krakelingen from Juergens at this hour, or a bratwurst dinner at Schmidt’s, followed by a peanut butter and chocolate buckeye at Schmidt’s Fudge Haus next door. It was too dark to try spotting feathery cosmos in my childhood backyard, let alone a goldfinch. That was the life I wanted, and this was the life I had: broken scooter, lonely moxa, frozen food.

The next day, my scooter negotiated the airport with ease. When the boarding announcement invited passengers in wheelchairs up to the gate first, I noticed a man in a wheelchair about ten years older than I. As the line of people with briefcases stirred with irritation behind me and my scooter, I stopped, beckoning to the man in the wheelchair to go ahead of me. That’s when I saw he wasn’t traveling alone. His elderly parents were pushing him.

After I reached my seat on the plane, the man’s parents buckled his seatbelt for him. His head lolled to the side but his eyes were full of expression. The man and his parents spoke to one another quietly. He was in a wheelchair in a way I that wasn’t: he required assistance full time. How old had he been when his parents realized they’d have to care for him until they died? The two old people moved with painful care. Who would look after them when they became too frail to care for their son? And who would look after their son?

I remembered my mother pushing me in that rented wheelchair, how suffocated I had felt by her fussing. I wished she were alive so I could bear her love with more humility. I closed my eyes and sighed. We would all have to stop traveling one day, I thought. But for now, we could. It was a small and hard-won thing: we could. It would have to be good enough.

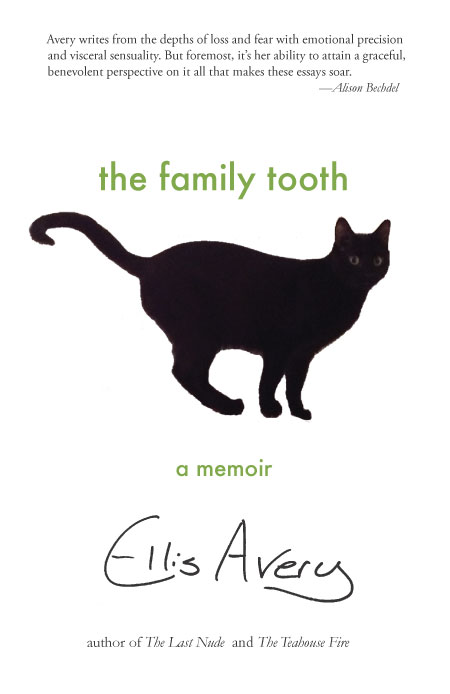

The only writer ever to have received the American Library Association Stonewall Award for Fiction twice, Ellis Avery is the author of two novels, a memoir, and a book of poetry. Her novels,