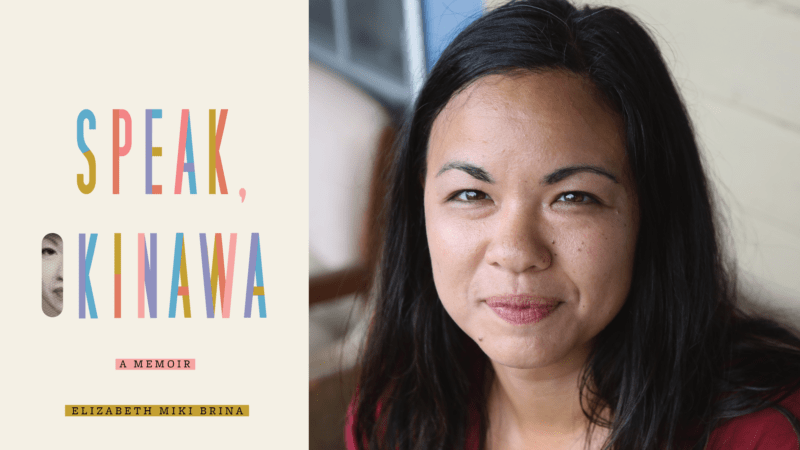

Elizabeth Miki Brina’s debut memoir Speak, Okinawa is a nuanced investigation of self, lineage, and inheritance. Born in the 1980s to an Okinawan mother and a white, American, ex-military father, Brina struggled with the duality of her identity. She connected more with her father—the dominant force in her family triad—often in an attempt to fit in with the 99 percent white suburb in which she grew up, and this made her feel distant from her already isolated mother.

It is only years later, after moving out of her parents’ enveloping orbit, that Brina comes to question why she feels so disconnected from her mother and Okinawan ancestry. She then sets out to explore her heritage—half that of the colonized and half that of the colonizer. We take this journey with her as she recounts the history of Okinawa. These chapters, voiced brilliantly in the first person plural “we,” tells the reader of Okinawa’s conquest by China and Japan, the horrors it faced in World War II—nearly a third of its population was killed in one battle alone—and the subsequent US military occupation of the island, which continues to this day.

As Brina learns the history of her maternal lineage, she comes to better understand not just her mother but herself. She is then forced to reckon with the role her father played in dictating her worldview and to try and unknot how America, as both a political entity and a cluster of ideals, has marginalized other ways of being.

I was dazzled by Brina’s fluid, beautiful weaving of the personal and historical in this work. On a Sunday afternoon, Brina and I talked over the phone about what sparked her work on this memoir, inherited trauma and inherited sin, and the importance of sharing the Free Okinawa! message.

—Elizabeth Lothian for Guernica

Guernica: Your retelling of the history of Okinawa plays a large role in your book. Towards the beginning you write that “I had not learned this history, my mother’s history, my history, until I was thirty-four years old. Which is to say that I grew up not knowing my mother or myself.” How did you navigate this process of research?

Elizabeth Miki Brina: My mother’s baptism gave me the initial spark. She had recently joined a church where all the members were Japanese; almost all of them were women; almost all of them were around her age. And this is what really blew my mind: most of the women were married to white, American men who had served in the military. That’s the first time I’d realized my parents’ relationship—which I had always thought was a big coincidence, a romantic love story—was not an isolated incident. That’s when I started the research.

I had absolutely no idea where to begin because there’s not a lot of Okinawan history written in English. The first book I read was about Okinawan history from the first settlers all the way to World War II. It was really hard to get through. It made me realize I wanted my book to sound very close and very personal. So then I started reading a lot of memoirs. I loved learning about history that way.

Guernica: The scenes pulled from your mother’s childhood were so powerful. You write of mornings in her home, the whole family waking up next to each other on the floor, and then washing themselves outside, one after another, with a bucket of water. Privacy of bodies is a luxury, you note, your mother and her family are not allowed. Were those details taken from memories your mother related to you? Did you have to delve into imagining what some of those moments must have been like for her?

Brina: I asked her as many questions as I could, and she gave me as many details as she could remember. It was harder for her to talk about things with direct questions—more things came out conversationally.

I had been to the house that my mother grew up in and she had also described it to me and told me about how her family all slept in the same room. As I wrote I was just imagining based on what I heard about each sibling, and my grandmother and my grandfather, what that would be like. Writing about it was really a way to connect with my mother.

Guernica: Before you started researching Okinawa, you note that what you knew about the island’s history was limited to what you may have learned in school, namely about the Battle of Okinawa as a footnote to World War II. As you learn more about Okinawa being conquered by various empires over time, you begin to understand how traumatic being colonized was, not only for your family, but also for Okinawan society as a whole. How did you come to recognize how that trauma became something you inherited from your maternal lineage?

Brina: The inherited trauma was something that I didn’t consider growing up in America. Even though I am half Okinawan, I still have this American mentality—having privilege, being the winner, having things just work out in our favor. Until I learned this history I didn’t fully appreciate what it’s like to grow up in a place where you have no power, no control. Where everything is being done to you, your voice doesn’t matter, your opinion doesn’t matter.

Even though I understand the psychology of that from growing up in America being a woman of color, I didn’t experience it in the sense of my national identity. Appreciating that my mother did grow up like that with this kind of ingrained inferiority was really important in understanding who she is.

But at the same time, Okinawans also have a lot of pride, too, because they’ve been through so much. As a society, they’ve maintained an incredible generosity of spirit and are very community-oriented. I think that comes from the mentality that “We’ve all survived. We’ve all had to do it together.”

The flip side of that is what I’ve inherited through absorption and internalization. While my mother was born three years after the Battle of Okinawa, everyone on the island was still traumatized by it. All of that grief she absorbed and internalized, and then she experienced her own personal suffering due to the militarization. That got passed down to me. It carries over in a new way. I had already been set up to move through the world a certain way, just because of what happened to my mom, to my grandma.

Guernica: You also go into how your father’s white, wealthy American side gave you another type of inheritance. You connect with him in many ways, whether through cultural references your mother isn’t aware of or through reading the “canon” of literature. But your kinship with your father’s perspective of privilege and whiteness changes over time. You have a lovely line, “I believe that we inherit sin as much as we inherit trauma, but maybe we also have a chance at redemption by being aware, being honest, giving up power, letting the world change, changing ourselves by apologizing, by forgiving.” How did you ultimately get to that understanding?

Brina: Thirty-nine years in the making! That was one of the hardest things growing up. I had a sense of privilege and yet it didn’t match with the world. I was like, wait, why do I get treated differently? Why doesn’t it work for me? All these “American ideals” that my father and a lot of men his age, and his time, believe were not my reality. I came to recognize that it is not the reality for so many people. So much has to be exploited in order for that mentality to exist.

Guernica: At certain times you are hard on your parents, and you are often especially hard on yourself. At the same time, you also allow for complexity. Your father’s political viewpoints are often problematic, but we also see him as a kind, encouraging father figure.

Brina: That’s the thing with inherited sin. I don’t think you get to evade responsibility. But also I can recognize that my father is not inherently a bad person. He didn’t get these ideas from himself. It’s constantly in the atmosphere, right? There’s a quote [from Beverly Tatum] that I come back to: “Racism is a smog.” We just breathe it in.

Guernica: That’s a great way of taking it beyond your father. In writing personal stories, it can be so hard to reveal negative aspects about people you care about, and even harder to reveal those things about yourself. Were those moments difficult to get into?

Brina: One of the reasons why I write is because of this incredible guilt. I need to get it out! When I write I can explain myself—this is what I did, but this is why I did it. A lot of the stupid things I did were because of the stupid things my parents did and I wanted to explain why they did those things, too. It’s only fair. It’s so hard to make yourself be really honest and not let yourself, or anyone else, off the hook too much. But that’s the reason why I write.

Guernica: While you recognize that you feel like an outsider in the suburb of Rochester, New York, where you live, it is only later that you understand the struggles your mother faced trying to assimilate in this relentlessly “American” space.

Brina: My mother had to make adjustments to all these Americanisms. You always think that your life is going to be better somewhere else, like if I could just get here, then everything will be great. And that’s how a lot of immigrants thought of America, right? As soon as I get there, it’s going to be so easy. And then it was just so hard.

I do think, for her at least, it may have been better here than it would have been in Okinawa, in some sense just in terms of financial security. But what really hurts me all the time is thinking that she had all these expectations, and then it was so hard for her in all these ways that she didn’t anticipate.

Guernica: The subjugation of the Okinawan people, as well as your own experience of being othered as an Asian American woman, fall into the framework of the conversations we’ve been engaged in on a national scale this past year especially as it relates to Black lives. Your discussion of the continued heavy American military presence Okinawa demonstrates that systems of subjugation and injustice are interrelated.

Brina: A big point that I wanted to make is this is all of our systems. I definitely wanted to show that connection.

It’s troubling. I can’t say I was entirely surprised. It’s going on everywhere America has a military base. These practices are carried over from centuries ago. I would venture to say that most Americans don’t even know that we have an active military presence in Okinawa, that the bombings in Iraq and Afghanistan, and that whole area of the world really, are coming from our insane military presence that we still have in Okinawa.

Guernica: One of the final, and most mobilizing, chapters ends with: “Free Okinawa!” How important is advocacy to your project?

Brina: I want people to know about this history because many do not know about it. But it’s also important to learn your own history—that is integral to understanding yourself. What’s happening now is complete injustice and I want people to know about that, too, and to be upset about it. We, as a country, are still hurting people. I also wanted to draw the connection to personal healing. It’s all connected. If you want to stop hurting people and you want to heal, the damage that has been done, that’s got to stop.

I think it really does manifest in our most daily intimate interactions within families and within communities. My whole overall healing intention is to remember that the historical and the personal are intertwined.