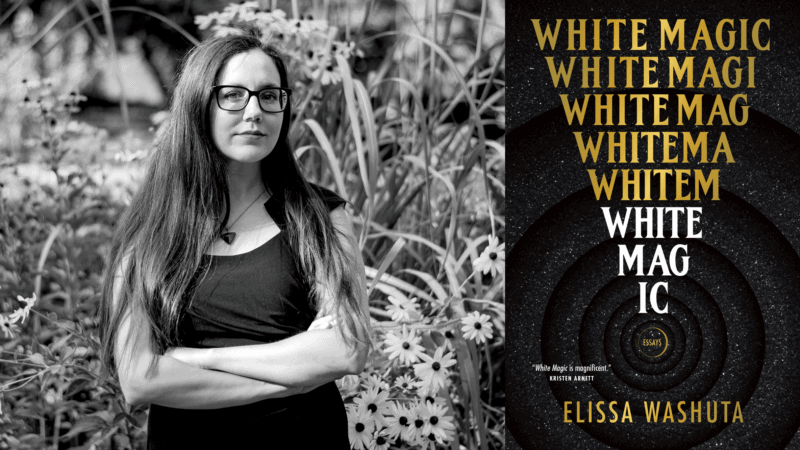

Elissa Washuta’s White Magic, her third book, a collection of exquisitely crafted lyric essays, is shaped like a visitation. Washuta is the protagonist and also something like an apparition bound by unfinished business, retracing her own pain and desire, cycling through her own patterns, conjuring meaning from repetition, collapsing linear time, circling, looking for a way out. “The internet says I will not release my karma across lifetimes until I learn my lesson,” she writes. “I am ready for this to be my last life. I do not want to come back.”

In one essay, Washuta sees herself from a decade into the future on a city bus. In another, she plays Oregon Trail II on an old computer and her white-man avatar travels west, as she herself did at twenty-two, journeying in a Chevy from New Jersey, where she was born, to Seattle, north of her Cowlitz ancestors’ territory, hoping to make a new start; she relaunches the CD-ROM over and over, searching the screen hungrily for the faces of her Native relatives, which she has been doing since she first entered the world of the game as a child. The book’s centerpiece is a hundred-page essay in which scenes from Twin Peaks: The Return and the same stretches from three consecutive years of Washuta’s life bump up against and tumble into each other, creating what she calls “time loops,” a scrambled diary through which men move, and hurt her, and leave her. Symbols recur, numbers reappear, astrological bodies pass in and out of alignment, proving or not proving that she and her ex-boyfriend are meant to be together. What is coincidence and what is meaningful? It doesn’t matter. Washuta is in pursuit of magic because magic is what gets her out of bed, it’s what “lets me live.”

When pressed to describe White Magic, Washuta says it’s “about how my heart was broken and how I became a powerful witch.” It is also, along the way, about PTSD and addiction and America and appropriative white witchcraft and tarot and Fleetwood Mac and the portal of the internet and the grievous effects of settler colonial violence on the body and Red Dead Redemption II for PlayStation. It’s about Washuta’s tremendous longing to be loved, a wanting she could only ever blot out with alcohol, and what it is like to grieve sober, “all electric feeling, no hiding place from pain.” Her incantations summon love, love summons agony, and agony calls for magic, for spirits and prayers. The sequence continues, the stakes are high. “If I don’t exit these time loops, these men echoing men, their cause, my effect, I’ll meet my tragic end. I’m saying a man might kill me if I keep choosing wrong.”

From these motifs and a fuck-ton of research Washuta builds essays that are funny and devastating, shrouded and encyclopedic, welcoming and wildly intricate, and that rise up all around you through some inextricable combination of content and form. They are meant to inspire wonder, and they do. I did not have any satisfying names for their design until I read Shapes of Native Nonfiction, the anthology she co-edited with Theresa Warburton that’s ordered according to formal basket-weaving techniques. Coiled baskets start at the center and mount in spiral rounds, and are sometimes woven so tightly they can be used to boil water. Washuta tells me that she thinks of the final essay in White Magic this way and I see it. Seamless, and scalding.

On the cusp of a second pandemic spring, Washuta spoke to me over Zoom from her home in Ohio about protecting Indigenous knowledge, astrology as permission to be yourself, and how “having hope feels so embarrassing.”

—Hillary Brenhouse for Guernica

Guernica: You mention, in White Magic, that you were going to write a novel about this old Cowlitz story in which a girl devours everyone who loves her—her husband, her husband’s other women, their baby—before turning into a shark. How did you realize that you wouldn’t be writing that book and begin to write this one?

Elissa Washuta: It became clear immediately that, first of all, I didn’t know how to write a novel; it’s its own thing. And I was not doing it for the right reasons. I didn’t really have any desire to write a novel. I like to read them, but at that point I was already thinking of myself as an essayist exclusively. This was before my first book came out, and my then-agent had gotten feedback from an editor who thought that the first book would have worked better as a novel. The agent and I agreed that that was not correct, but he said, “To take your mind off all these rejections, maybe you should work on a novel.” I really wanted to produce something that would be easier to sell, or that would sell at all, because there was a question about whether that would happen with my first book. I tried to get started with the potential novel, I created a lot of long and very detailed outlines, I wrote many pages of a single scene in which the protagonist was lying on her couch, eating salt bagels, getting high, and watching Shark Week. And I realized, I don’t want to write a novel; I just want to write about myself, like always. I felt uncomfortable with the idea of representing experiences that I’d never had, even if they were close to my experiences and the protagonist was basically me.

Guernica: A version of the first essay in the book, about appropriative white witchcraft, ran in Guernica in 2019. When we initially talked about the possibility of the piece, you wrote to me, in an email, “I’m not really sure where the essay will go—such is my process.” What does that process look like? How much uncertainty do you let in?

Washuta: I definitely did not realize at the beginning of that writing process that I was working on something that would be the opening of the book, which I’d been working on for quite a long time. I didn’t intend for it to be in the book at all. And I think that this is something that happens a lot with me: I’ll start with an idea that feels like it is very separate from whatever my major obsession is at the time, and somehow I always get back to the same place. The most prominent pattern in my drafting is that I’ll have a sentence or a few words, a phrase, that are just kind of repeating themselves in my head over and over and over constantly until it finally feels like I just need to get them out. There’s some indescribable feeling that I get when I know it’s time to start writing something. Usually, I get the first paragraph down and that is always doing a lot of work in setting up form even if I don’t have intentions for the form at the time; it’s setting up voice and it’s setting up an attitude toward the subject matter that I’m going to be working with for the rest of the essay. And I’ll often just leave it at a couple of paragraphs because that’s all I can do when I first start, and then the process begins of emailing myself links and notes and doing that unconscious work when I’m away from the essay. And now I’ve gotten so far away from your question [laughs]. I guess this is how the essays work, too.

I try to really make space for the writing process to follow this kind of thinking process, where something will be on my mind a lot and the real reason that I’m thinking about it or worrying about it or obsessing over it is because of the same old stuff that I’m always working through. I try to let the essay represent that experience in life by leaving it open-ended and not tethering myself to any one outcome. It makes it more alive on the page, too, to not know what’s going to happen. It’s something that keeps me invested.

Guernica: In that same first essay, you write, “I google spells to take the PTSD out of me. But is that what I want? To stop my brain from thrashing against the wickedness America stuffed inside?” And you quote Leanne Betasamosake Simpson, who writes that she doesn’t necessarily want to heal, because she isn’t damaged or unhealthy but reacting to the intergenerational trauma of settler colonial violence. How do you conceive of the desire to heal from pain when you know that the body is responding properly, and warning you?

Washuta: This is an ongoing question for me and one that I only just began to open up in White Magic. I’ve been writing more about it in work I’ve done since finishing that book. I think that the desire is a really basic one, to just feel some relief, some physical relief. At the same time, and this is part of what I’m writing about now—I’m writing about chronic illness—for years doctors have told me that I need to find ways to alleviate my stress, that my stress is making me sicker, that this is a symptom exacerbated by stress and this flares because of stress. And it really puts the impetus on me to destress myself when it is impossible. It’s just not possible. I can’t see a way to do it. This is the world I’m in. This is the past I have. Living inside this empire is all that I will ever have and there is no way out of that. I know what I know, and that has dramatic effects on my body. It feels like it could be comforting to know that this is normal and it is a correct response, as Simpson writes. But I don’t think that makes it any easier.

Guernica: You’ve written a magisterial essay in which episodes of Twin Peaks and the same period from three consecutive years of your life wind around each other. You’re focused here on the order of things and how they happen in relationship to one another, and on recurrences and synchronicities. Tell me about the role of repetition and time loops in this work, and how you’ve used these to create links and conjure meaning.

Washuta: I was inside the experience of drawing these connections in life enough to capture it on the page, but I was also self-aware enough to be able to point it out for what it was, which was me trying to find signs from the universe to confirm things as I wanted them to happen. I knew these synchronicities were happening in mid-2017; that’s when I started to notice the Twin Peaks universe coming into my universe. I didn’t at all think that that was going to be part of the book. But once I got to Ohio and I was just really… kind of… I don’t know if “lonely” is the word… Well, “lonely” is definitely the word. Homesick. Lonely. Not exactly bored, but I was definitely in this weird in-between space where the movers hadn’t brought all of my stuff yet from Seattle to Ohio and I just had this couch that I bought and I was watching Twin Peaks: The Return as the episodes were coming out. And I was feeling guilty for spending all this time watching Twin Peaks and reading astrology stuff, trying to figure out whether my ex-boyfriend and I were destined to be together, and I was about to start my tenure track job at Ohio State and I thought, I can’t keep doing this. I have to be an adult. So what I need to do is make this the thing I’m writing about so all of this becomes research.

Guernica: I know that strategy. I love that strategy.

Washuta: It’s at the core of everything I do. I think making that decision, that this was going to be something I was going to try writing about, was really kind of freeing and a catalyst for all of this getting written; a large portion of this book was written after July 2017. I had decided that I was going to completely give myself over to the investigation that I was interested in, which was my ex-boyfriend. I had been trying to figure out what I was working on for years after finishing my first book, and finally something clicked, and I let go of something having to do with what I thought I should be writing—what I thought would sell or get me a job. I just let go of that, and I thought, I can just start by taking notes on everything. It felt like so much of the way I was thinking about this relationship had to do with time, with astrological events, with the dates when there were planetary aspects that went direct and how that coincided with the day that he was upset at me about something or whatever. I could see that I always had an obsession with time. I’ve always known that and I realized that that was something that I still had not investigated at all and was going to need to really reckon with.

Guernica: You quote Astrida R. Blukis Onat as saying that most old legends weren’t structured to have a beginning, middle, and end. The storyteller didn’t need to finish the story and often wouldn’t. This is comforting to you, as an essayist. But in a different context, nonresolution is problematic; you write, “my stressed, post-trauma brain didn’t believe that the story of my body in danger was over.” What does resolution mean to you, and does it play out similarly in a book and in a body?

Washuta: With this book I genuinely didn’t know how I was going to exit it. I didn’t know what the ending was going to be and it felt very, very important, not just to the book but in my life. I felt like I actually needed to resolve something through this book. That’s what made this process I was talking about earlier so important, of not knowing where the essay is going to end up, the book being a big essay. I knew it could finish when I got to a certain point of realization in the essay about Red Dead Redemption II; I was playing video games and had been playing video games for twenty hours a day for a week when it happened. I had an insight there that really felt profound. The reason I was unable to extricate myself from this relationship patterning was something that was right there in front of me the whole time, and I had been writing for thousands of words to try to figure it out. I think that once I got there, I really did get closure from this book. Right there in that essay, that was where I finished the unhealthy relating. It completely changed my life to finish writing it. It really did make those patterns end.

Of course, I still have PTSD and I still have the trauma I carry and the ways that I react and behave that are rooted in trauma. But I already knew taking control of narrative to have been really powerful in my life, because when I was diagnosed with PTSD, long after it began, a new psychiatrist told me that it was clear that making narrative with my first book had been a legitimately healing act. It hadn’t gotten me nearly as far as I would need to go in healing from PTSD, but he could tell that there had been utility for me in the meaning-making process of articulating my story for myself. And I really held on to that and I believed that to be true and I let that be a mechanism of this book.

Guernica: It struck me that you didn’t have to embrace the narrow definition of narrative as linear in order to find resolution.

Washuta: I think that the way that plot is talked about is really limited. It certainly has seemed truer than ever the last year when fewer things are “happening,” but so much is happening. For all of us who are spending most of our time at home there’s still so much happening, even though we’re doing the same routines. And that’s because events are not just external happenings. Going back to the novel I tried to write, that’s what really threw me, just making up stuff that was going to happen. I thought it needed to be about a character moving from place to place and interacting with people, because that’s what plot traditionally is. I think [White Magic] has a plot, but it’s more of a plot of me, the writer, working through something by writing essays. And figuring out how to get over this inconsequential relationship.

Guernica: It’s right here in the book: “This book is a narrative. It has an arc. But the tension is not in what happened when I lived it; it’s in what happened when I wrote it.”

Washuta: It was very hard for me to adequately describe the pain I was in when that breakup happened. A lot of people in my life thought I was really, really overreacting and feeling way too much and emoting way too much and hanging on for far too long. I don’t think I could even have articulated for myself easily at that time why I was in pain. I think that that’s really what I needed to do through the book, try to show that it wasn’t about my ex, it was about feeling like magic was happening. And never having felt that since childhood. It was devastating to lose that.

Guernica: In the book, you tell us that you’ve tried to hide your “driving obsession to be loved” by reciting incantations and to obliterate it with alcohol. And yet you normalize this desire so beautifully, writing, about Lucifer lusting after the same supernatural power as the divine, “What is spirituality if not lust? How could such pure, potent want be evil?” How has your thinking about your own wanting transformed over time, as you’ve become sober and written it into the center of this book?

Washuta: I think I still struggle with it a lot. Not romantically. But I notice it a lot more now that I’ve written so much about it in that realm. I notice it professionally. Like, how so many of us have such a hard time sharing our professional goals with anybody because how dare you want that award, how dare you want that job, who do you think you are? I’ve thought about that a lot since writing this. Just wanting any small comfort. Wanting conditions to be better in any part of life. There’s just such an immediate response from so many people to shut it down. What did you think was going to happen? Well, what do you expect? This is the way things work. And, like, why? I think that I’ve really noticed since writing about it that having hope feels so embarrassing. It feels like it’s childish and naïve. I don’t want to be constantly resigned to the way things are because they are that way. Of course, it’s been very hard the last year to have any kind of imagining of the future, so very hard to have any kind of hope, but I’m still trying. I’m trying to have hope. I’m noticing that in myself when I get embarrassed about it.

Guernica: You write about places that are safe only because they’re secret—hidden gathering locations, fishing spots—and also about silence as protection, about safeguarding the unseen because so much of the seen world has been colonized. How do you decide when to stay silent when you’re writing? How to write what you need to and meet this need for silence?

Washuta: I think that’s a big part of the revision process for me. I try to just let my first draft be where I can write anything. I don’t usually get myself into situations where I’m going to need to show the work to anybody; I don’t have a writing group or anything like that. I keep the work protected for as long as I can so I can consult with others and do my own thinking about that issue separately from the many questions and lines of inquiry that are in my head when I’m drafting. With “White Witchery,” I kind of freaked out during that process of writing it and realizing, I’m not sure about all of this; I’m going to need to check with some people about whether they think I’ve said too much. And so I showed a few people. I’ve tried to be a lot more deliberate than I used to be in my practice of revision and getting input on matters of what I should say and what I shouldn’t say when it comes to Indigenous knowledge. And I try to err on the side of not saying enough for the reader. I try to revise to the point where I feel very confident that the work is exactly what I want it to be and any reaction the reader has is their own.

Guernica: I want to talk about astrology and the role it plays in your life. You describe the positioning of the planets at your birth and then write, “I choose to believe it to be auspicious. It is significant because it is mine.” You treat it as a way of believing—your way of believing.

Washuta: After I finished writing this, I stopped really checking up so much on the planets’ positions. I have a partner now and I actually don’t remember his placements at all. We’ve been together a while now. I’ve seen his chart, but I don’t remember where his moon is, where his rising is. That’s a real change for me. The main thing astrology has done for me is, in the birth chart, it’s given me a way to visualize myself as a set of traits, not like a person who is constantly on a path of self-improvement and trying to escape myself. There’s a way of looking at my chart and seeing the way I am in there. It kind of gives me permission to be myself. And the other big thing about astrology that has been useful for me is remembering that time happens. In periods of despair, it feels like it’s going to be the same forever, and that I’m always going to feel this way, and the thing about paying attention to transits and cycles is they can’t stay the same. Saturn can’t stay in my sign forever. It’s going to be different in a moment. If nothing else, those things have been really useful for me to believe. I also believe it’s true; I believe in astrology. Maybe it isn’t real, but I don’t care, because when I’m paying attention to it, it means that I’m paying attention to the idea that there is some unknown, mysterious force out there. And by force I don’t mean God; I mean there is a body of knowledge we don’t know. The way the universe works. And my life is way better when I am aware of that than when I’m not.