By Elisa Albert

1. Office at home

Set up your office and get to work, a friend instructed a few years back, when I complained about the novel, which had plateaued at halfway done and was now just sitting there. I half-heartedly poked at it a few times a week, but the momentum was gone. So I put down an old Ikea kilim, cleared out clutter per the Feng Shui guru, hung pink string lights and cute scrap flags someone sewed me as a gift and a photograph of a feral house in Detroit (which has a thing or two in common with downtown Albany). Suspended some tillasandia with twine. Now I had a nice quiet little room to sit in and contemplate the stalled novel.

Just doing the work is the whole battle, we always say: making contact. Sit with the novel, be in it. Turn off the internet so you have nowhere else to go. Only rarely is it satisfying. Rarely is there a great chunk you can point to at the end of a day and say, here is what I did today! More often there’s the vague fear you’ve made no progress at all. Where did those hours go? Where is your work? What is this adding up to? You have paid someone else to be with your child while you did this bullshit? The thing continues and continues to feel like a wreck. But it’s your wreck. And you are working on it, even when it seems like bullshit, eating your time and appearing none the better. No effort is wasted, says the Bhagavad Gita on a post-it I stuck to the bottom of the giant computer monitor. But God, some days are a slog.

2. Leaning against doorjamb while boy plays in the bath

The battery on the old laptop is shot. I’ve got fifteen, twenty minutes, max. Fewer if I start up iTunes. Fucking machine. It gets hot and gives me a headache. But fifteen minutes is about the length of the bath, so it works out.

My son still seems pretty little, but maybe it’s because the novel is about early motherhood, the desperate combat-zone-like surreality of it.

Little over five years old, the machine. The boy’s a little under five years old. The machine arrived just before the boy. When it wouldn’t start one day I marched it dutifully to the Apple store in the heinous mall, where I was told by a sweet young lady that they would not be able to service it.

“It’s a vintage machine,” she explained.

“It’s five years old,” I said. She nodded at me slowly.

There must be a better way. Pen? Paper?

The boy will be five soon. He still seems pretty little, but maybe it’s because the novel is about early motherhood, the desperate combat-zone-like surreality of it. It still takes my breath away, how scared I was. He’s not a baby any more, but he’s so precious I can taste the fear even now.

He practices back-floats in the bath. He makes waves. He’s in trouble if he sloshes too much water out of the tub. He dislikes washing his hair, which is copious and curly and a delight. When he was three and had a bad fever he slept on me for hours, waking only briefly to whisper that his “curls hurt.”

It took me over a year to begin to write again after he was born. I was freaked. I couldn’t relax. I didn’t know how to let go. I didn’t trust that it would come back, that I would come back. Insanely confusing time. I have a beautiful man and child. With them I felt anxious and trapped; apart from them I felt anxious and lonely and cast off. The problem, obviously, was me. I was panicked and impossible, incessantly looking for trouble. I wrote my way out of it. I am ashamed of my faithlessness.

3. Starbucks

In the midst of horrid urban sprawl on a four-lane road lined with car dealerships and half-abandoned strip malls, new gas stations, old abandoned gas stations, and parking lots, are restaurants that serve nothing remotely quantifiable as nourishment. Nearby are the tiny Jewish guild cemeteries founded back when this would have been way out in the countryside. Albany Jewish Tailor’s Assoc. Albany Jewish Stonemason Assoc. Now the cemeteries are crowded around with the malls and gas stations and motels and car dealerships and big box stores. If the weather’s nice, take a stroll through a cemetery before settling down to work. The children’s section is rife with tiny headstones that say BABY OF MRS [whoever]. Or just BABY BOY.

When the kid was tiny and he would only reliably nap in the car, this Starbucks drive-thru saved my bored, thirsty ass more times than I care to remember. I sat in this parking lot with a book while the kid slept for what must add up to whole days of my life. I amused myself by taking an ongoing series of car-nap selfies. Look here: I was still an artist. The car-nap-selfie series would surely change the way people thought of early motherhood and urban sprawl. Instagram much preferable to the infinite silence of writing. No dozens of orange heart notifications occasion completion of an insightful sentence.

Across the highway are two huge malls. Everyone looks like death warmed over, the walking dead. Zombies don’t know they’re unhappy, right? Or is it precisely the appeal of newfangled undead narratives that there might be zombies with angst? I thought the whole issue with zombies is that they lack the depth, the consciousness, the temerity, the bravery, the decency to wrestle with angst. To understand that they’re unhappy.

Anyway, the first mall was built on a geological rarity, the pine bush. Habitat of the New Karner butterfly, so named by Nabokov. Valiant protests by environmentalists notwithstanding. We call this first mall the Democrat mall, because it’s showing its age and is so circa-1984 ugly it’s almost sort of cute and everything about it is so shabby and second-rate you have to love it a little. (Excepting the pristine Apple store, which belongs in the second mall, really.)

The second mall is known as the Republican mall, because it’s newer and shinier and there’s a rambling Cheesecake Factory that might as well be a nineteenth century Opera House for the way the McMansion crowd gets dolled up to go wait in line there on weekends. Spanx city.

Both malls are depressing as shit, needless to say, unless it’s the dead of winter and you just need to get out of the house, in which case: what a treat! The Democrat mall’s not so bad around three or four on school days right when the kids are starting to gather, because suddenly there’s this infusion of life instead of the shuffling zombies, all of whom look about four decades older than they are. No one can stand up straight, lots can barely walk, they hobble, they limp, the women are losing their hair and people wear these permanent expressions of surprise and fear. Because movement and fresh air and clean food and water and a quiet burial plot under some trees far, far from a highway are 21st century luxuries, marks of extraordinary privilege. Because lots of people have surrendered these things, or been robbed of them, or some nefarious combination therein. During the first Iraq war, mall security infamously ejected a man wearing a “Peace on Earth” T-shirt.

So long as you have your headphones and a good book and a pen and a seat on the Hudson River side and are dressed for the weather. So long as you don’t forget your headphones.

But back to the Starbucks across the highway. They’re playing old-old Billy Joel. There’s a beautiful pre-op male-to-female barista. I’m cross-legged in an upholstered armchair drinking an iced tea. A man just sat down in the next chair. We share a side-table. He’s reading the Travel section. He’s tapping his foot to the old-old Billy Joel. He looks lonely. He’s got nice energy, a turquoise pinky ring. Possibly I’m projecting about the lonely part. Possibly I’m projecting about the nice energy part. We say nothing to each other. The community bulletin board by the toilets is glaringly empty.

4. The train

Down to NYC and back home again the next day. It’s like a vacation, a parallel life. I wouldn’t beg Amtrak for a residency on one of these barreling old overpriced tin cans, but it’s not so bad so long as no one left trash/food/perfume on your seat earlier in the route. So long as you have your headphones and a good book and a pen and a seat on the Hudson River side and are dressed for the weather. So long as you don’t forget your headphones.

5. On break at the Food Co-op

It was lonely, moving up here. I joined the co-op straight away. Figured I would find my people. It was made clear that to be nominated for a slot at the cheese counter is quite the honor. All the cool people work in cheese. Produce might beg to differ, and bulk seems kind of fun, but in cheese there are free samples to give out, and a boom box, and the beloved cheese monger, who is given to fits of operatic Italian.

The co-op’s a mile from downtown, tucked behind a Family Dollar. Soon it will move to a hotly contested new building even further from downtown, but closer to the highway. There will be more parking, gleaming poured concrete, a bigger café, and shiny everything, but people will complain bitterly that it has lost its soul.

For now, soul intact, it’s a charming rabbit warren with a tiny potholed parking lot and an appropriately surly, dreadlocked staff. There is a beautiful personified sun painted on the wall by the produce (“Hi, sun!” my boy calls out in greeting) and a blue sky with fluffy clouds painted on the ceiling (“Hi, sky!”).

I think of my great-grandfather with the shovel, those tiny inanimate bundles, one after another. Where did he bury those boys?

My maternal great-grandparents owned and ran a grocery store in Larksville, Pennsylvania, near Wilkes-Barre. Met at an immigrant dance on the Lower East Side, got married in rental attire at sixteen, seventeen. Had four boys and four girls. The boys all died in infancy, “some genetic thing they could fix like that today,” my mother tells me, snapping her fingers.

Can you imagine? Four dead baby boys. Rabbi said no funerals for the dead boys, just showed up with a shovel and accompanied my great-grandfather on a walk in the woods to bury the things. You can’t officially mourn a child unless it lives at least 30 days. Which is only practical: a few dead babies were par for the course. You’d be in constant mourning if you went through the whole rigmarole every time. I think of my great-grandfather with the shovel, those tiny inanimate bundles, one after another. Where did he bury those boys? Was there a marker? Was he the kind of man who cried?

But the four girls all lived. And went to college. Louis and Dora Levinson, immigrant grocers too busy staying afloat to mourn their four dead baby boys, sent four girls to college in the 1930’s. Girls! To college! During the depression! Can you imagine?

Great Aunt Miriam, the youngest of those girls, tells me the Polack kids used to chase her home from school, throwing rocks, shouting dirty Jew, dirty Jew. But also it’s said that Lou and Dora were fairly popular in town despite being dirty Jews, since they extended a great deal of credit to many families during the hardest years. My mother’s cousin Lou, named for his grandfather, tells me all this. Latter-day Lou still lives in Wilkes-Barre, in the grandest old stone house in town. He’s an obstetrician. “You’re so lucky,” Lou says of my having given birth perfectly fine at home without machines or scalpels or needles or electronic fetal heart monitoring or synthetic drugs or forceps or whatever other routine barbarism women are routinely brainwashed into thinking they need. He used to love to torment me about feminism when I was like nine. Lou’s alright, though. A sweet man. His loyalty to Wilkes-Barre, to the family, to our common history, is admirable. He’s the pride and joy of the whole immigrant narrative, and he knows it.

Dora lived to be an old, old lady, obsessed with American soap operas (from which, it’s said, she learned English). She lived to see her four daughters grow up and have children and she lived to see those children nowhere near the working class. She lived to be an old lady with plastic cat-eye glasses on a chain, in a top-of-the-line recliner with a gorgeous brown and yellow and orange zigzag afghan she made herself covering her lap, watching soaps.

There’s one picture of her and me. She’s smiling, reaching up to squeeze my fat infant hand. But she doesn’t hold me. Her second daughter is newly dead. My mother, her granddaughter, is blond and beautiful and educated and privileged and batshit crazy, a world and a half away from whatever shtetl hut Dora’s mother’s mother kept clean. A world away from four dead baby boys buried without fanfare God knows where near Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania.

An announcement over the muddy PA sounds like David Grossman, line 1. Phillip Roth, line 2.

The key to grocery life is FIFO (first in, first out). I receive delivery from the organic dairy in Cohoes. The delivery guy is nice and has one of those interesting faces you can’t stop seeing. In a yoga workshop, instructed to send loving kindness to someone we see often but don’t know well, it was his face that came to me.

The co-op is good work. Better than teaching writing, possibly. The pay’s probably not so different. I have room to think here. Mindless pricing, breaking down boxes. Lots to observe. An announcement over the muddy PA sounds like David Grossman, line 1. Phillip Roth, line 2.

Terry is my shift-mate. We price and carefully stack egg cartons. He tells me about his big Italian family, his cute boyfriend, his marathon running. The assistant cheese monger is funny and fraternal and blushes outrageously over not much. It’s someone’s job to guard the meat, just sit in a chair opposite the cheese counter and make sure no one steals meat. Word has it there was a spate of meat-stealing recently, so now someone sits, keeping watch. We bond, the meat watcher and I, when he tells me about his wife’s impending homebirth.

Someone in produce offers to sell me weed, but I have a superior source already.

There’s a guy who scares me. Easy to imagine him shooting the place up. Everyone would say, “Yeah that guy, he always seemed a little off.” Everyone always says that after someone shoots someplace up. I learn to avert my eyes, try not to be noticed. I will play dead in the event of a shoot-up. I will curl up face down under that counter and play dead and he won’t notice me and I’ll live to hug my family and suffer constant nightmares forever after. Or maybe it will happen at the mall. One of the two malls. Which mall will it be? Or maybe it will happen at the school. Oh please, please, please not the school.

I am invited to select a CD for the boom box one day and I am thrilled. But it turns out the cheese monger can’t stand Bob Dylan. You just don’t understand him, I say. It is the very wrong thing to say.

I scribble in my notebook when there’s something worth scribbling.

Are you writing about us in there? They ask.

No, I say.

I invite them to a party but no one comes.

I get comments about what I’m wearing. This is one of my least favorite things about living up here. Sorry if my outfit is calling attention to itself. It makes me happy. I miss New York City. Don’t trouble yourself over my tiny opacity, to paraphrase Phillip Roth.

I start to feel like I’m in high school, where every conversation is sort of over my head but degrading in some way because I’m weird and my clothes are wrong or my clothes are right or I’m not cute enough or I’m too cute or who the fuck knows. And I’m supposed to laugh at myself. Or not laugh. It can be exhausting to live in a cosmopolitan place where everyone is oh so sophisticated and up to date and worldly; that can be stifling and irritating, too. But I long for it sometimes. Because, what, I’m not allowed to wear anything you don’t recognize from Target?

The scary guy seems to chill as the weeks roll on and I stop trying to smile or make eye contact, just lower my head and say “Yes” or “got it” or “sure” or “no problem” when he tells me to do something. He seems to like me better, to relax a little, when I behave this way. So the eye contact was the problem. All my stark naked smiling.

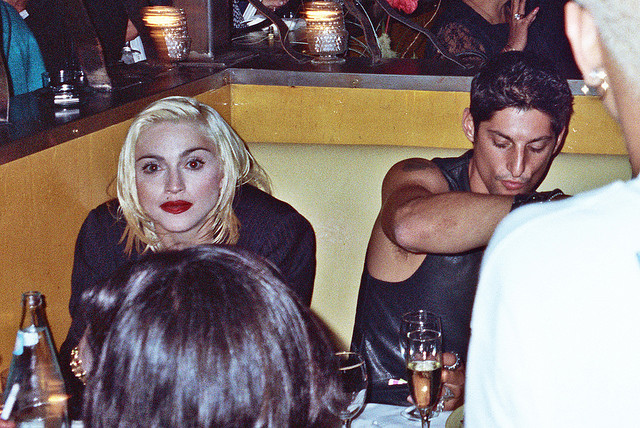

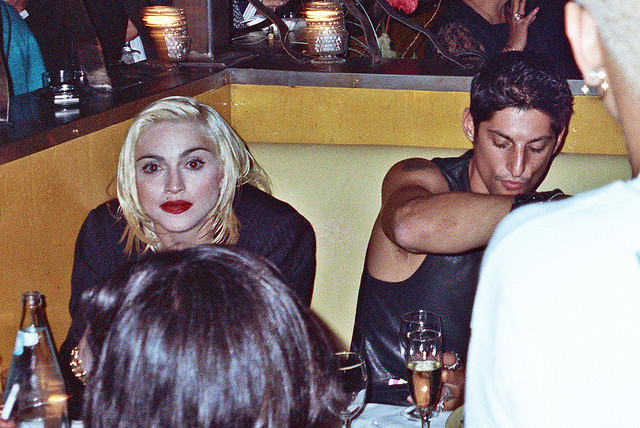

Madonna is on my headphones. I’m not, she sings, I’m not very smart.

I run into my husband’s ex-girlfriend. I like her. So desperate for community here!

I’m like a foot taller than she is. Ungainly. Thirteen again—beastly, breasted, bearded—towering above the cute compact girly girls. How could anyone want to be friends with me? So bumbling, awkward. Also she used to sleep with my husband and a former lover and not one but two favorite writers. (Not all at once, I don’t think.) I don’t care; I’ll be Sister Wives if she wants. I’m into that.

There’s a long-haired woman I start to see regularly. She is pretty and has a toddler and I think, in this annoying way I tend to think: “We are totally going to be friends!” But she is cold and does not respond in any way to my dorky overtures and even though I’m sure she’s just “shy” or some shit, I of course wind up strangely hurt and cold in return. Which is exactly where being desperate for community gets me. Which is exactly why I have to stop this ridiculous “we are totally going to be friends!” bullshit. She won’t even say “hi” to me. I get right up in her face one day, and smile, and say, “hi.” It’s like some kind of punishment, my “hi.” Like: I see you and I know you see me and pretending otherwise only adds to the tremendous unhappiness in this difficult world, so what the hell would it cost you to say hello?

I’m learning how to keep myself to myself, let people slowly earn my confidence. This might sound obvious to some, but I’m slow. (I’m not…Not very smart.) Thus far I have specialized in zero boundaries, almost like an ethos, and it has rather sucked. You know how it is: little poisons seep slowly or the rising tide of resentment rushes in all at once. Or silence speaks for itself. Or secrets or lies or jealous third parties or misunderstandings or new friends you like better or you change or they change or whatever. People you thought you’d love forever become strangers, and you’re not sorry. Cutting attachments so much easier now than it used to be, wow. Easy! Bye.

I put on Dylan singing “Most of the Time” when it was my turn with the cheese department boom box. I don’t build up illusion ’til it makes me sick. I ain’t afraid of confusion no matter how thick. “Turn that maudlin shit off,” the cheese monger hollered. Then he did the easy, mocking Dylan impression. I played it loud, later, while I did the dishes at home. I’m clear focused all around. I can keep both feet on the ground.

Anyway, that spring wore on and every Friday there seemed to be some better thing I needed to be doing. Like writing. In my little office, or leaning against the doorjamb by the bath, or at the Starbucks out by the malls and cemeteries, or on the train. Because the novel was closer and closer to done. And I had this obvious realization: the sooner I stop spending Fridays at the Co-op, the sooner I will finish my novel. And writing! What a relief. Because writing is not about making friends.

Elisa Albert is the author of The Book of Dahlia and How This Night is Different and the editor of Freud’s Blind Spot. Her new novel, After Birth, will be published in February.