Hujar had wanted his service to be at the Church of St. Joseph after attending a funeral there in May for his old friend Charles Ludlam, star, director, and playwright for the Ridiculous Theatrical Company. I still recall the horror and dismay that swept through the theater community when Ludlam died of AIDS mere months after his diagnosis. A friend of mine had been to that funeral, and she described how, in all that collective grief, “the church lifted up.”

It was a time to worry about friends—and all the other brilliant, aspiring, wild spirits who’d landed in what we then called “downtown.” We were not prepared to see each other die.

Suddenly we were living in apocalyptic and elegiac times. Every day now began with a look at the obituaries. I could sense the path of the virus around me, the tornado that devastates one house and leaves the next pristine. It was a time to worry about friends—and all the other brilliant, aspiring, wild spirits who’d landed in what we then called “downtown.” We were not prepared to see each other die.

Tom Rauffenbart told his doctor that he did not want an AIDS test. That was the general consensus among gay men in 1987. Why be tested when there were no treatments to look forward to—only depression, only stigma. “Everyone was afraid their name would end up on some kind of list,” Tom said. But when his doctor suggested a T-cell test instead, Tom agreed. He did not know what a T-cell was. The count that came back was between five hundred and six hundred, indicating that his immune system was somewhat compromised. (A healthy immune system has five hundred to fifteen hundred T-cells per cubic millimeter of blood). He went to get an AIDS test when he learned that the city’s public health clinics would do it anonymously.

And so, two to three weeks after Hujar died, Tom learned that he was HIV positive. When David came over that night, Tom told him, and they both cried.

The struggle for so many now was with how to process all the loss, knowing that there would be more loss.

David had a rubber stamp made that said, “A celebration of Peter Hujar, where he lived, 189 Second Ave, Sunday December 20 1987 1-5,” and sent out notices to friends. He had hung Hujar’s photographs all over the walls and set up a sort of shrine with candles, Hujar’s glasses, and the photos of gurus Hujar had kept by his bed. There were no formal talks recounting poignant or humorous moments with the deceased. Much of the time, David simply stood by the door welcoming people.

He wrote of later “coming back to his place the candle and shrine had burnt down to a beige hard puddle. I told him out loud how sad I am… I can’t imagine my life without this man… My conversations with him even when depressed or afraid always had some reassuring calm. Somewhere in the midst of the fear surrounding the problem he could reach right in with little effort and the result was clarity and suddenly allowing yourself strength in a way that seemed right: healthy and real. I felt this sadness all day and night.”

David had decided to move into Hujar’s loft. He would breathe the same air Hujar had breathed. He would hang on to any vestige. He would leave the phone and utility bills in that name, keep “Hujar” coming to the space. He even saved the junk mail that came for Hujar and at some point tried to stitch it all together to use as background for a piece, the way he used maps. He could hide now, with his name no longer in the phone book. (His mother, for example, never knew where he was living after 1987). He had his mail from Thirteenth Street forwarded to Tom’s house.

Moving to the loft also solved a practical dilemma. He’d been offered a lease extension at his Thirteenth Street apartment, either $982.50 a month for one year or $1,015.86 for two years—rather steep for a dump between Avenues A and B in 1988. His rent there had more than doubled in two years, as his landlord kept getting “rent adjustments” upwards. That didn’t bode well. Meanwhile, Hujar’s rent was $375. Tom remembered David moving to the loft at the beginning of January 1988.

For years, David had been telling people that his career was in trouble. It was one of the first things he had told Tom about his life as an artist. Schneider and Erdman remembered the only time Hujar ever got mad at David: One night, years earlier, when Hujar had them all over for dinner, David said he was going to have to take a phone call from a journalist who was fact-checking—and this article was crucial because his career was in the toilet. Hujar angrily told him it was wrong to put something like that ahead of dinner with friends. But now, as 1988 began, David’s career was genuinely in trouble. He’d had two shows in ’87 and sold one piece. The art world had moved on to Neo Geo and Jeff Koons. The East Village was passé, and David was its emblem. He ended 1987 with $166.53 in the bank. Given that David liked to be paid in cash whenever possible, that may not accurately represent his worth. Still, he had a real reason for concern.

On January 20th, he applied to the Pollock-Krasner Foundation for a grant, listing his ’87 income as $4,125. He also stated that from 1985 to 1987 he had given more than $12,000 to Peter Hujar.

Later, he said that he wished he could have filmed the snowstorm that suddenly engulfed the car on the interstate and the pack of dogs on the road all standing around one dog who’d been hit by a car, who lay there not moving.

But he did not go back to making work he could sell. Instead, he began a new journal, in which he wrote that he was going to “film the process of grief.” He drove out of the city one day to film whatever his intuition led him to, and that was the Great Jersey Swamp: “virgin forest primordial place where dinosaurs once slept—all these heavy storm grey clouds these days—huge dark flapping wet curtains over the stage of this earth.” In that passage, he’s actually evoked his painting “Wind” (for Peter Hujar) with the images of dinosaur, clouds, and flapping curtains. But then, for him, everything he encountered resonated with emotion, with his feelings for Hujar, which he had probably never expressed while Hujar was alive and struggled to articulate now, through the camera. He ran, “shooting automatic bursts of film,” then went whirling through the trees, filming as he spun until he was nauseated. “Felt my body in some strange way its mortality, its thumping heart, its fear, and loss its small madnesses.” Later, he said that he wished he could have filmed the snowstorm that suddenly engulfed the car on the interstate and the pack of dogs on the road all standing around one dog who’d been hit by a car, who lay there not moving. “In the driving snow, one by one they sniffed at its form unwilling to leave it behind.”

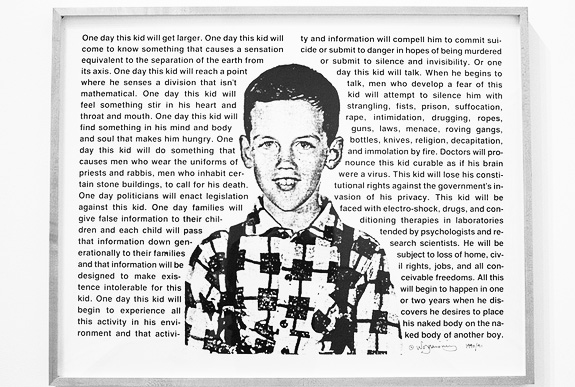

Back at the loft, David filmed all the pictures of Hujar he could find, beginning with one little school photo of the unloved kid Hujar had been.

He filmed Jesse Hultberg’s dream of shirtless men passing the prone body of a man from hand to hand. Jesse, eyes closed, took the role of the man gently being passed along. He may have filmed this even before Hujar’s death. Jesse remembered only that it was an image David wanted. David worked on the Hujar film on and off for about a year, and never finished it. But it goes to the heart of what he was doing with his films. He used the camera to capture something that connected him to the world, that allowed him to react emotionally, and though he had to wait to get the film developed, it seemed instant. It was as immediate as speaking into a tape recorder or pounding out pages at the typewriter, but those two options did not give him a visual image. And he wanted to record each telling detail, like Hujar’s bathtub filling with dead leaves that blew in through a vent in the ceiling.

As he tried to understand his loss, he saw that Hujar was one of the first people he ever truly trusted, though he realized, in talking to others, that they’d known a different Hujar. Sometimes he felt he was listening to descriptions of a stranger. The pain he felt confused him, overwhelmed him. David began therapy in January 1988. After his first session, after trying to explain how he felt about Hujar, he drove directly to the Coney Island aquarium to film the beluga whales. He had visited there with Hujar and Charles Baxter, and then he’d been moved by a news photo of a girl granted her dying wish to swim with dolphins.

A lot of his artwork came out of feeling like an alien. Learning that he wasn’t alien at all, he worried that the realization would block him from making his work.

Now he connected Hujar with the “sad innocence” of those whales. “All the mysteries of the earth and stars are contained in their form and their imagined intellect,” he wrote in his journal. But their glass case was empty. They’d been shunted off to some shallow pool for a few days, and he left the aquarium immediately. He was obsessed with getting the images he wanted. “When I can’t complete an action, I am confused. My emotions won’t allow a detour or a wait. It’s beliefs like this that kept me alive all these years. And it is in this season that for the first time these beliefs are falling apart. It started with Peter becoming ill.”

Around the third week of January, David went back to Mexico with Tom and Anita and a dozen other people to celebrate Anita’s fortieth birthday.

Rick Morrison, a friend of Hujar’s, knew a woman who rented houses on the beach in Progreso (near Mérida in the Yucatán)—right on the gulf and very cheap. David, Tom, and company rented two of the houses, along with three cars. When they arrived, Morrison was there with his boyfriend, Larry Mitchell, and their friend Bill Rice, the actor and painter who’d once hosted David’s monologues in his “garden.” They overlapped for a couple of days. Which was good for David because he and Anita were not getting along.

Anita and David hadn’t exactly hit it off when Tom first introduced them in 1986. “It wasn’t instant dislike,” Anita said of meeting David. “It was, ‘Who are you and why are you taking Tom away from me?’” But then she and David bonded while caring for Hujar. When they went to Mexico, however, she had just started therapy with someone who urged her to stop taking care of other people, to just take care of herself. “I decided to take that to the next level. I wasn’t going to help anyone,” Anita said. “And that wasn’t me either. That’s why the therapy didn’t last all that long.” David thought she was being cold and mean.

Tom took Anita out to lunch to discuss it, and she changed her approach. From this point until the end of David’s life, he and Anita were truly friends. Tom said, “This wound up being—even David admitted—one of the best trips any of us have ever had. We were there for a full three weeks. He and I stayed longer than anybody, but it was really a great trip.”

As they drove away, they came upon a vulture in the road, clearly dying. David wanted to stop and pick it up. But there was nothing they could do for it, and Tom said, “David, we are not putting a dying vulture in the back of this car.

David flew from Progreso to Mexico City for a few days to take pictures. When he came back, he’d brought everyone presents. Anita had never seen him in action before. “David was taking pictures of all the stray dogs and the roadkill and the vultures,” she said. “He’d take out his camera and just shoot out the window while driving. It was amazing to me.” She asked him about what he was doing. “He said, ‘I see the world as just these images—constantly, constantly, and my art is how I organize this.’ He was stimulated by everything. He didn’t sit quietly much.”

David would see vultures aloft and say to Tom, “Let’s go see what they found.” One day the two of them made a day trip to one of David’s favored sites for shooting pictures—a dump. This one was outside Mérida. David climbed up a mountain of decaying garbage to photograph packs of wild dogs and people competing for scraps of food, their mouths and noses covered with bandannas. “There were flies as big as parakeets, and it smelled,” Tom said. “I refused to get out of the car.” As they drove away, they came upon a vulture in the road, clearly dying. David wanted to stop and pick it up. But there was nothing they could do for it, and Tom said, “David, we are not putting a dying vulture in the back of this car.”

Activists in San Francisco had come up with the idea for the AIDS Memorial Quilt in the summer of 1987. Mourners all over the country immediately began sending three-by-six foot panels commemorating lost loved ones to the sponsoring NAMES Project Foundation.

I witnessed the first display of the AIDS Quilt on the National Mall when I went to Washington, D.C., in October 1987 to cover a huge gay rights march. The panels were stitched together into squares of eight and unfolded ritualistically. Step back, grab a corner, turn. It was choreographed. Constructed with varying degrees of craft, some incorporated clothing or other belongings or photographs of the dead. People walked among the squares of fabric, crying. The size of two football fields and destined to get much larger, this was Arlington for PWAs.

David designed a quilt panel for Hujar and worked with Sur Rodney Sur and Melissa Feldman to create one for Keith Davis. On Keith’s panel, made from pink tie-dye, David stenciled the two men kissing from “Fuck You Faggot Fucker.” For Hujar’s panel, he created a large version of the Dürer wing, with a globe below it, for one half. Then on the half with Hujar’s name and dates, he added the image of a figure climbing a tree without branches. This was almost the same image he’d painted for Gracie Mansion’s “Sofa/Painting” show in 1983, which she explained as David trying to get away from the various dealers who wanted to show him. But while in the earlier work, he gave himself one short branch. Hujar, even more devoted to self-sabotage, had none.

David also began to design Hujar’s tombstone. “He barely even wanted a gravestone,” David told me one day at the loft. He pointed at the arched window behind the blue table. “It’s that shape, like an Old West tombstone.” Just his name, his dates, and the Dürer wing.

David had always thought that he would die before Hujar. He knew he was at risk, and when he got depressed about it, he took comfort in imagining Hujar still there in some room, talking about him, explaining him, not letting him vanish.

And I was afraid for him. I was afraid for me… We were screaming like banshees. Having AIDS does strange things to your emotions.

And now he faced the possibility of losing Tom. “He was very sweet with me, and helpful,” said Tom. But Tom thought that David should get tested too, and one night they had a big fight about it out on Second Avenue near Ninth Street, in front of a funeral parlor. “I thought he was probably HIV-positive,” said Tom. “I remember getting pissed off that he’d treat me like I was infected, while he could go on not knowing his own status. I was feeling that what was going on between us was really false. I said, ‘You’re not taking care of yourself. You could be infected too. What are you doing?’ And I was afraid for him. I was afraid for me. It was one of the many hard times in our relationship. We were screaming like banshees. Having AIDS does strange things to your emotions.”

David had stopped making art. He felt that he couldn’t create anymore. He was horribly depressed.

Meanwhile, Luis Frangella had introduced his dealer in Madrid to David’s work, so when Galería Buades invited him to show there in April, he agreed to come a week ahead of time and make several new pieces. Before he left town, though, he wrote down all his fears. The major one, of course: “I’m afraid that I will come down with AIDS.” But that spun out into so many others: the fear that this would be his last work before he got ill; that if he sold work in Spain, they wouldn’t pay him; that the lump in his arm would turn out to be cancer; that the landlord would try to get the loft back; that he’d have to move in with Tom, where there was no place to work and the cats would get into the paint. Then, he had not filed a tax return, so the IRS might get him. “I have Tom but I’m too fucked up to let myself be loved and maybe so is he… I live like I will die and I wonder how I can shift in therapy when I am so closed up and when I am so self-destructive… I can’t let myself hate my mom and dad for what they did. I see it all as my responsibility. Why is this? I’m afraid of my anger that lies buried, afraid if I experience it I will not be able to control it.”

He’d gotten a big shock when he started therapy. It turned out that half of what he’d kept hidden were emotions everyone had! A lot of his artwork came out of feeling like an alien. Learning that he wasn’t alien at all, he worried that the realization would block him from making his work.

He flew to Madrid on April 8th. The paintings he made there were done quickly, and while they were less complex than most—even perfunctory—they were also the beginning of new ideas. “Childhood,” for example, features an empty wire head with orange balls for eyes against a background of clouds. It looks very much like the surrogate mother given to orphan monkeys in test labs. Embedded circles down each side feature some familiar iconography—dinosaur, steam locomotive, erupting volcano, a fetus in a hand. In “Mortality,” an elephant in a pond walks up to a floating elephant fetus. All around this image are both veins (attached to a heart) and vines. Later in the year, he would begin “Something from Sleep II,” an important painting that combines and complicates the imagery from both “Childhood,” and “Mortality.”

He began to recover some energy here. He jotted ideas for photo diptychs, paintings, and “sound sculptures” in his journal and made notes to himself like, “call Washington zoo for whereabouts of Tasmanian devil in U.S. zoos.”

After the opening in Madrid on April 18th, he flew to Paris. He may have seen Jean Pierre during his week there, but if so, he did not see much of him. David stayed with his sister, Pat, who was about to have her first child. At 6:30 on the morning of April 20th, an alarm went off in his sister’s bedroom and was not turned off, so he got up and saw that she and her husband, Denis, were gone. He was deeply upset that they hadn’t taken him along to the clinic. He cried. He wrote in his journal that he felt unwanted. “I sometimes think maybe it’s because I’m queer,” he wrote. “Maybe they are afraid of what I carry, if I have AIDS or not. This fear returns often. Maybe they won’t allow me to see the baby until some time… I ask myself if it’s my imagination… because then it could all be something grown out of nothing—the way I sometimes tend to do—when I imagine the worst rejections or actions and project them onto others who I place in power positions… I see myself taking my bags and leaving in anger. I am unhappy with my thoughts. Angry. I want to cry and turn to someone bigger than me—emotionally or physically bigger. Am I a child again in this state?”

While David was beginning to understand that he often saw rejection where none was intended, he still felt completely miserable until Pat’s husband called at 6:00 p.m. to tell him that the baby had been born. David then went to the clinic.

David, however, did not want to hear about T-cell numbers. He asked the doctor to just let him know when there were few enough that he could give them all names.

He took a photo of his new niece—which he would soon incorporate into a piece called “Silence Through Economics.” And he tried to imagine “this large creature” emerging from his sister’s body. “Pat’s belly, the light from the window upstairs, the color of the baby’s skin, red, then faint, then red, tiny fingers with tiny nails, little working mouth. Peter. Peter’s death. The shape of the earth clouds stars and space. The darkness of the delivery room shadows around the floor and ceiling all the memories in those shadows like films.”

He went out and took a long walk.

Maybe that day, maybe the next, David was walking near the Centre Pompidou when Michael Carter, editor of the East Village zine Redtape, popped out of a restaurant to say hello. Carter pointed inside to the window table and the person he had been sitting with: Marion Scemama.

“I didn’t know if David would come to me, and then he came,” Marion said. “So it was weird. All of a sudden, we start like the old days.” They hadn’t seen each other in two years, but they saw each other every day for the rest of his visit. They went to the catacombs. They walked all over Paris, and one day, passing a store that sold animals, David said, “Let’s buy some mice so we can free them.”

“We were like kids,” said Marion. “We were very happy to meet again, without all the past. Everything restarted as if nothing happened. So he bought four little mice, and we took them to the Jardin des Tuileries.” When they saw a cat, they decided they couldn’t free the mice there. Marion took them home, where one escaped and she had to recapture it before driving the mice into the country to set them free after David left town.

Marion had learned of Hujar’s death from Nan Goldin and thought about calling David then. “But I didn’t dare,” she said, “because when I left New York, we were not really friends.” David told her about his depression and that he wasn’t working, and he seemed obsessed with his garbage. He told her he would take his trash ten blocks away, and he tore up everything that had his name on it. This was probably because he was living in the loft illegally, but Marion thought he’d become paranoid.

“I remember I had this feeling that I owed a lot to this guy and maybe he needed me,” she said. “I’m not a mystical person, but there was something very strong for me in the fact that we met in Paris by chance. It was unbelievable. That Michael Carter looked out the window at that moment, and that David was passing by—I had the idea that it was not just chance, that it was meant. There was something written somewhere that we had to meet again. And I had the feeling that if something permitted that, it’s because I had a role. I had something to do for him.”

After David returned to New York on April 26th, he and Marion began talking on the phone again—calls that lasted two or three hours. At some point they decided it would be cheaper if she just came to New York.

David decided to get tested for HIV after he came back from Europe. He never said why he changed his mind.

Tom had found a doctor he liked right there in the East Village. Dr. Robert Friedman also happened to be a gay man, and he ended up with a large caseload of AIDS patients. That’s where David went for his test. That’s where he learned that he was HIV-positive. Not only that—he had fewer than two hundred T-cells, and two hundred was the line of demarcation. In other words, said Dr. Friedman, “David had full-blown AIDS from the time he walked into the office.”

However, since he had no opportunistic infections (like Kaposi’s or PCP), he was given a diagnosis of ARC, or AIDS-related complex. “It was a euphemism that made people feel better,” said Tom. The term was eventually deemed useless.

David’s T-cell number would fluctuate. Somehow he got hold of one of his own lab reports in 1990, showing a count of 237. But Tom eventually learned from the doctor that from the time of his diagnosis until his death, David rarely had more than a hundred. David, however, did not want to hear about T-cell numbers. He asked the doctor to just let him know when there were few enough that he could give them all names.

He left the doctor’s office on First Avenue that day of his diagnosis and almost immediately ran into Bette Bourne, the lead Bloolip. They’d only met once or twice before, possibly at the Bar or through Hujar, but David immediately went to Bette with his overwhelming news and said, “I’m fucked. What am I going to do?”

“He was sort of smiling,” said Bette. “It was very strange. It was one of those smiles of recognition and resignation. He was almost laughing at the horror of it. He was still in shock. We held each other for a bit.”

David tried to sort out his feelings by pounding out a couple of pages at the typewriter. The moments after diagnosis “were filled with an intense loneliness and separation,” and he realized that “even love itself cannot connect and merge one’s body with a society, tribe, lover, security. You’re on your own in the most confrontational manner.”

He did not make note of the day he was diagnosed. Tom remembered only that it was in spring 1988. But sometime before May 19th, David wrote a short disquisition on death in his journal: “So I came down with shingles and it’s scary. I don’t even want to write about it. I don’t want to think of death or virus or illness and that sense of removal, that aloneness in illness with everyone as witness of your silent decline.” He had discussed it with Kiki though—you become fly food.

David was thirty-three when he got what was then considered a death sentence. The man who’d run down the street as a boy yelling, “We’re all going to die!” had no illusions about “beating” the virus. He expected no miracle. Instead, he began to approach each project as if it were his last.

Copyright ©2012 Cynthia Carr

Reprinted by permission of Bloomsbury Publishing, Inc.