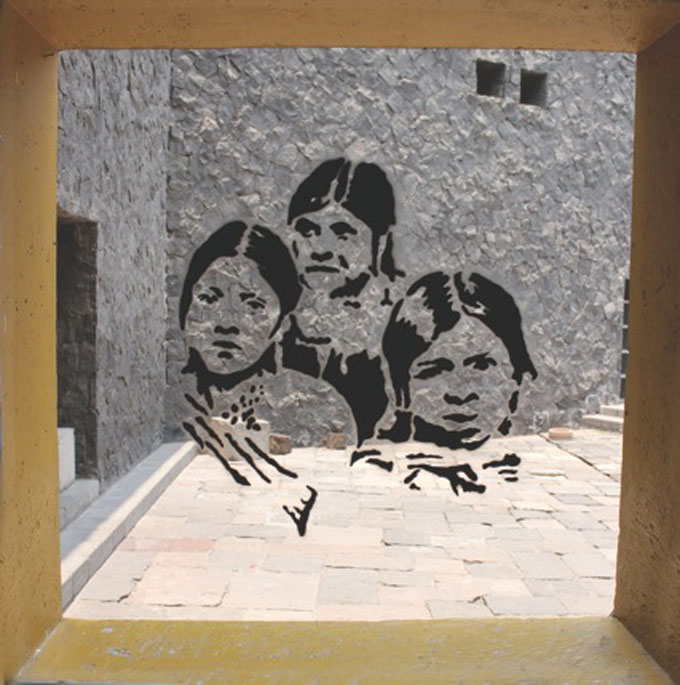

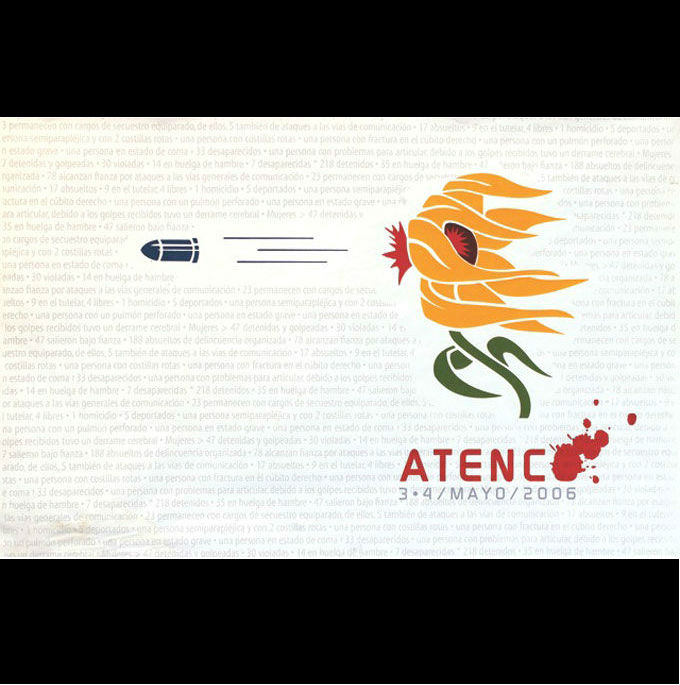

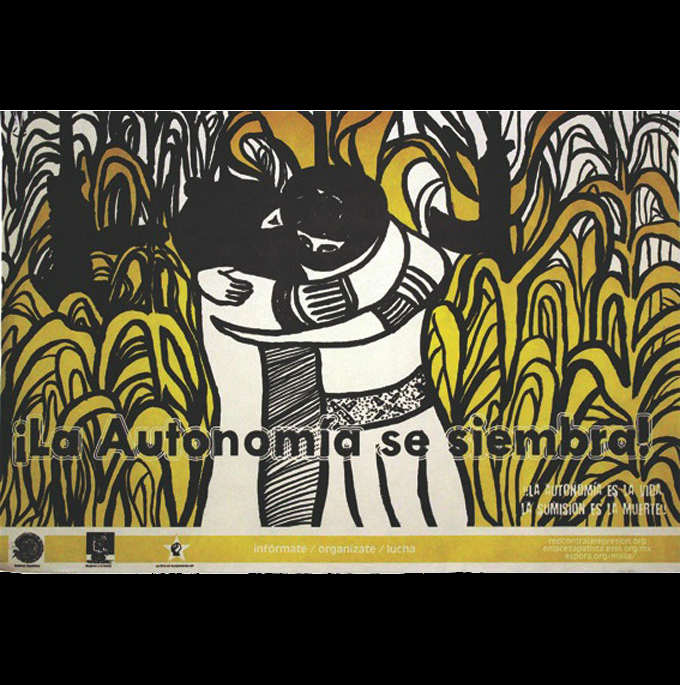

ECPM, Atenco, 2006. This poster was designed one month after clashes between the people of San Salvador Atenco and the municipal, state and federal police over the government’s intention to expropriate communal lands for a new airport. Tension began when the police tried to prohibit flower vendors from selling in their usual locations. Many were detained, raped and killed.

By ECPM

Translated by Yisa Fermin

By arrangement with Creative Time Reports

“October 2 is not forgotten.” We repeat these words to commemorate the massacre of students in the Tlatelolco neighborhood of Mexico City in 1968, when a student movement transformed Mexico’s history. As in other parts of the world, the social environment at that time was characterized by protest against “the system,” and the government responded to any demonstration with repression. The conflict between the state and dissenters actually began with clashes between students from the National Polytechnic Institute (IPN) and the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM) following a football game. The government used this clash as a pretext to deploy police to IPN and arrest various politically active students. In protest, students started mobilizing. The student movement, which was supported by farmer and labor organizations, demanded the repeal of articles within the Federal Criminal Code that labeled protests a criminal form of “social dissolution” and served as the legal instrument for attacks on students. Throughout the summer of 1968, the police and military met demonstrations with increasing force and further campus invasions.

On October 2, ten days before Mexico was to host the Olympics, thousands of students gathered to protest at the Plaza de las Tres Culturas. Hundreds of demonstrators were detained, and there is still no official death toll. The Mexican government claims only twenty to thirty were killed, while the BBC reports the death toll as likely between 200 and 300, with some speculating that thousands died that day. Witnesses spoke of cranes picking up corpses to burn them. When the “Olympic Games of Peace” took place that same month, there was no mention of the Tlatelolco massacre.

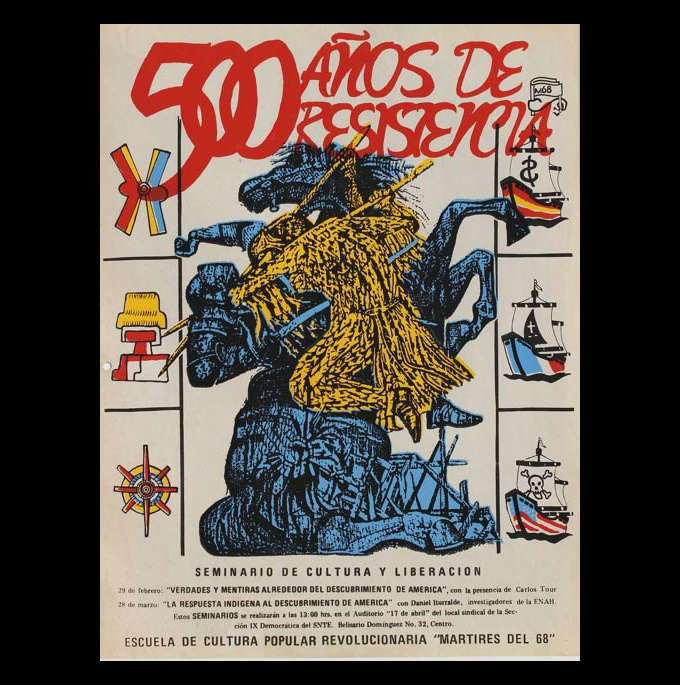

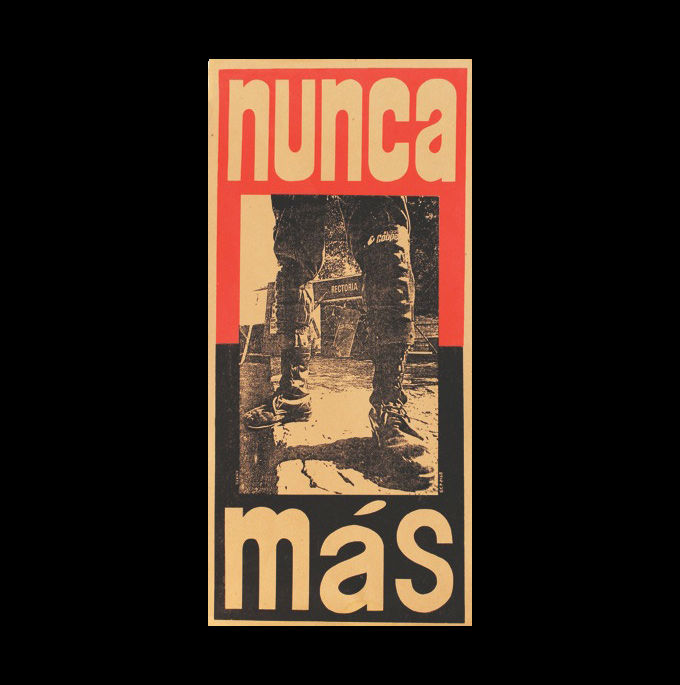

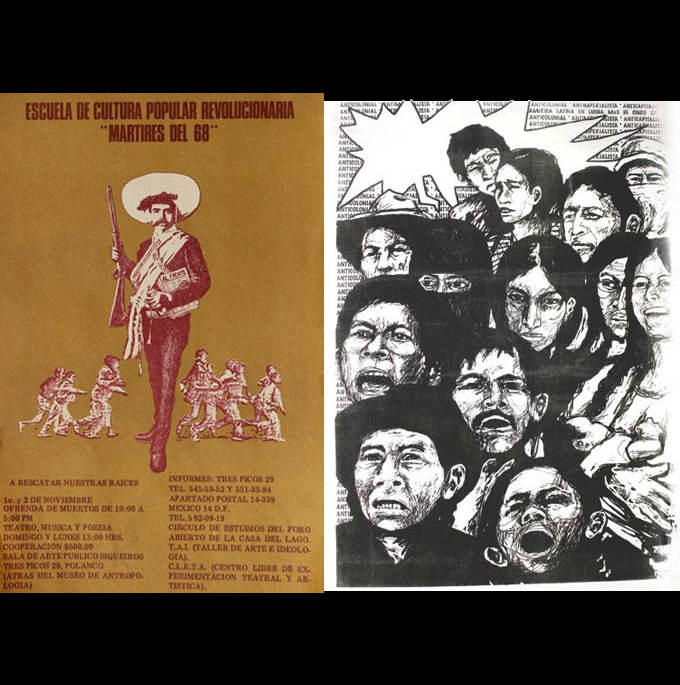

Graphic art has long accompanied Mexico’s democratic movements, serving as an instrument of denunciation and information, a call to the people of Mexico and elsewhere, and a tool for the organization of their struggles.

The Escuela de Cultura Popular Revolucionaria Mártires del ‘68 (The Revolutionary Martys of ’68 School of Popular Culture), or ECPM, opened on January 9, 1988, in Mexico City’s Siqueiros Public Art Hall. Since then, ECPM has had six different headquarters, but it has now been steadily located in the Obrera (“Workers”) neighborhood of Mexico City for a decade. The founders called our collective a “school” because their goal was to participate in social change by creating multidisciplinary cultural workers with theoretical and practical knowledge, who are committed to socialist transformation. They named the school “Martyrs of 68″ to pay tribute to the student movement from twenty years earlier, and to recognize and remember the assassination of peaceful demonstrators. For us, that massacre represents the arbitrary power the Mexican government has historically exerted in its repression of the people.

Today, we maintain relationships with social and community organizations and continue to support demonstrations, squats, rights advocacy and political and cultural participation. The ECPM has joined several calls from the EZLN (Zapatista National Liberation Army) since 1994, the year in which the EZLN became a civil association. In 2001, the school gave refuge to international brigades who came to support the Zapatistas’ Earth’s Color March. It has also supported the Zapatistas’ 2005 manifesto “Sixth Declaration of the Lacandon Jungle,” and its accompanying political program, “The Other Campaign.” These acts of solidarity are not exceptions. Various protest and resistance groups from communities throughout Mexican territory have often supported one another. Among these are the Zapatistas, the Atenco and Cheran movements, youth movements for freedom of the media, student movements fighting the privatization and subordination of universities, workers struggling against the mining industry and the exploitation of natural resources and teachers defending their rights to fair labor practices and to have a voice in decisions about national education.

Graphic art has long accompanied the country’s democratic movements, serving as an instrument of denunciation and information, a call to the people of Mexico and elsewhere, and a tool for the organization of their struggles. Members of the ECPM as well as other artists and cultural workers have participated in this process, shaping contemporary images of the country and the world. Today, the school is home to the graphic arts collective Malla, formed by ECPM members, and other collectives, including Sublevarte Colectivo and Mujeres Grabando Resistencias, that produce posters and prints based on current affairs. We are currently making art in support of the teachers’ movement seeking national education reform, for freedom of expression and information, and against the repression and criminalization of protests.

Below is the essay in the original Spanish:

“El 2 de Octubre no se olvida.” Repetimos estas palabras para conmemorar el masacre de estudiantes en el barrio de Tlatelolco de la Ciudad de México en el 1968, cuando un movimiento estudiantil transforma la historia de México. Como en otras partes del mundo, el entorno social en esa época se caracterizó por protesta contra “el sistema,” y el gobierno respondió a cualquier manifestación con represión. El conflicto entre el Estado y los disidentes comenzó con enfrentamientos entre estudiantes del Instituto Politécnico Nacional (IPN) y la Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM), tras un partido de fútbol. El gobierno utilizó este choque como un pretexto para desplegar la policía a IPN y detener a varios estudiantes políticamente activos. En protesta, los estudiantes comenzaron a movilizarse. El movimiento estudiantil, que fue apoyada por organizaciones campesinas y obreras, exigió la derogación de los artículos en el Código Penal Federal que declaro protestas como una forma criminal de “disolución social” y sirvió como instrumento jurídico para atacar a los estudiantes. Durante el verano de 1968, la policía y los militares combatieron las manifestaciones con un aumento de fuerza y nuevas invasiones del campus.

En Octubre 2, diez días antes que México iba a organizar los Juegos Olímpicos, miles de estudiantes se reunieron para protestar en la Plaza de las Tres Culturas. Cientos de manifestantes fueron detenidos y aún no hay cuenta oficial de muertos. El gobierno Mexicano asegura que solamente 20-30 fueron asesinados, mientras que la BBC informa que la cuenta de muertos es entre 200 y 300, mientras otros especulan que miles de personas murieron ese día. Testigos hablaron de grúas recogiendo cadáveres para quemarlos. Cuando los “Juegos Olímpicos de la Paz ” tuvo lugar ese mismo mes, no hubo ninguna mención del masacre en Tlatelolco.

La Escuela de Cultura Popular Revolucionaria Mártires del 68, o ECPM, se inauguro el 9 de Enero del 1988 en la Sala de Arte Público Siqueiros de la Ciudad de México. Después de su fundación, la Escuela ha tenido seis sedes diferentes, pero ahora se ha situado de manera constante en la Obrera, barrio de la ciudad de México, por una década. Los fundadores llamaron nuestro colectivo una “escuela” porque su objetivo era participar en el cambio social porque su objetivo era participar en el cambio social a través de la creación de los trabajadores culturales multidisciplinarios con un conocimiento teórico y práctico, que están comprometidos con la transformación socialista. Llamaron a la escuela “Mártires del 68″ para rendir homenaje al movimiento estudiantil de hace 20 años, y para reconocer y recordar el asesinato de manifestantes pacíficos. Para nosotros, ese masacre representa el poder arbitrario del gobierno Mexicano que ha históricamente ejercido en la represión del pueblo.

Hoy en día mantenemos relaciones con varias organizaciones sociales y comunitarias, y apoyamos sus manifestaciones, defensa de derechos, y participación política y cultural. El ECPM se ha unido a varios llamamientos de el EZLN (Ejército Zapatista de Liberación Nacional) desde 1994, año en el que el EZLN se convirtió en una asociación civil. En 2001, la escuela dio refugio a las brigadas internacionales que vinieron a apoyar a la marcha Zapatista del Color de la Tierra. También apoyo el manifiesto Zapatista del 2005 “Sexta Declaración de la Selva Lacandona,” y su programa político que acompaña, “La Otra Campaña.” Estos actos de solidaridad no son excepciones. Varios grupos de protesta y resistencia de comunidades en todo el territorio Mexicano se han apoyado mutuamente. Entre ellos están los zapatistas, a los movimientos de Atenco y Cherán, los movimientos juveniles de la liberación de medios, movimientos estudiantiles que luchan contra la privatización y subordinación de la educación universitaria, trabajadores que luchan en contra de la minería y la explotación de los recursos naturales, y a los maestros en su justa lucha por tener voz en las decisiones del tema educativo nacional.

Las artes gráfica han acompañado movimientos democráticos del país hace mucho tiempo, sirviendo como un instrumento de denuncia e información, un llamado al pueblo Méxicano y de otras partes, y una forma para la organización de sus luchas. Los miembros de la ECPM, así como otros artistas y trabajadores culturales, han participado en este proceso, dando forma a las imágenes contemporáneas del país y del mundo. Hoy existe dentro de la ECPM el grupo de convergencia gráfica Malla, formado por integrantes de la escuela y otros colectivos, como Sublevarte Colectivo y Mujeres Grabando Resistencias, que producen carteles en función de los temas de interés de estos días. Actualmente se están haciendo trabajos gráficos en apoyo al movimiento magisterial, que lucha contra la reforma educativa nacional; por la libertad de expresión e información; en contra de la represión y la criminalización de la protesta.

Escuela de Cultura Popular Revolucionaria Mártires del ‘68 (The Revolutionary Martyrs of ’68 School of Popular Culture), or ECPM is a cultural organization that supports radical democratic movements in Mexico and elsewhere through the arts, education and social struggle. Founded in 1988 as a tribute to the students killed in the Tlatelolco massacre, the school has historically offered theoretical workshops on topics including the history of Mexico, dialectical and historical materialism, Marxist aesthetics, campaigning, and image production. More recently, ECPM activities have greatly diversified to include theater workshops, contemporary dance, nutrition, photography, screenprinting, engraving, tai chi, bookbinding, karate, music and a “Seminar on Culture and Liberation.” In the twenty-five years since its founding, the ECPM has maintained relationships of solidarity with many social and community organizations and supported ongoing demonstrations, rights advocacy and political and cultural participation. Members have participated in roundtables, conferences, portfolios, exhibitions and a variety of forums ranging from the lower house of Mexico’s Congress and the Legislative Assembly of Mexico City to the Zapatista Aguascalientes (cultural spaces for meetings). The school has joined several calls from the EZLN (Zapatista National Liberation Army) since 1994, the year in which the EZLN became a civil association.