Adrian Tomine’s characters frequently observe each other across distances both real and metaphorical. In one of his best-known cover illustrations for The New Yorker, “Missed Connection,” two young urbanites, each reading a copy of the same book, glance at each other longingly from aboard trains headed in opposite directions. In another Tomine work, a bookstore owner and his neighbor lock eyes while the latter receives a package from Amazon. In a recent Drawn & Quarterly compendium, The New Yorker’s art director, Françoise Mouly, writes that Tomine’s images “often hinge on the electricity generated by people looking at each other.” Tomine can tell an entire story about contemporary experiences of isolation, yearning, and missed connection in a single drawing.

It’s a talent that he has cultivated for over twenty years as an indie cartoonist, starting at the age of sixteen. Tomine grew up in Sacramento, CA, the son of divorced parents. He and his mother moved frequently when he was a kid. “I had a lot of experiences of starting up at a new school and leaving friends behind,” he says in the interview that follows, “which is the perfect recipe for staying in your room and practicing drawing.” Inspired by the ’90s DIY movement and cartoonists like the Hernandez brothers and Harvey Pekar, Tomine created his own comic, Optic Nerve, in high school. The first print run was twenty-five copies, self-published at the local copy center, and distributed to friends and family. Soon afterward, he arranged to sell them on consignment at local comic stores. Prominent cartoonists, including Peter Bagge and Chester Brown, began to recommend his work in their own comics, and Tomine soon gained a following. In 1994, Drawn & Quarterly, an important art comics publisher based in Montreal, started to distribute his work.

Tomine’s early success also meant that he attracted some harsh criticism. His readers complained that he, a Japanese-American, failed to portray Asian-Americans or grapple with race in his work. Tomine bristled at this, and in 2007 published his rejoinder, Shortcomings. The graphic novel explores the life of Ben Tanaka, a young, single, Japanese-American man whose attraction to white women draws indignation from his Asian-American friends. Shortcomings—darkly funny and unexpectedly poignant—was named a New York Times Notable Book in 2007. But the book further rankled some of Tomine’s readers. He tells me, “I think there was a sense that I was one of the few people from the Asian-American community who had an opportunity to get work out there, and I didn’t use that opportunity in the way they wanted me to.”

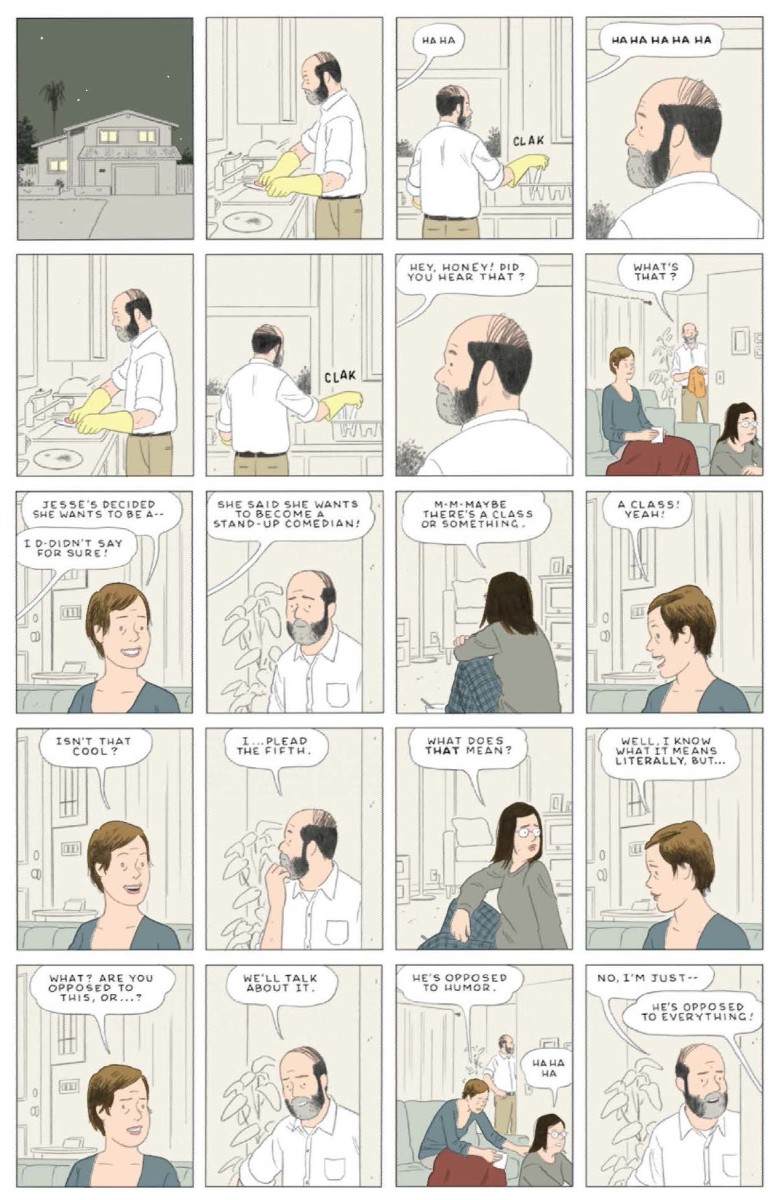

Killing and Dying, Tomine’s new graphic novel, is out this month from Drawn & Quarterly. Unlike much of his previous work, which primarily follows narratives of romantic relationships, Killing and Dying focuses on familial relationships, particularly between parents and children. In “Hortisculpture,” a father insists on pursuing his practice of making bizarre front-lawn art, to the dismay of his young daughter. In the title story, another father and his teenage daughter argue about her aspirations while her mother slowly succumbs to cancer. Although readers may sense that Tomine empathizes primarily with his fictional patriarchs, he says, “I felt myself in the position of the parent as much as the child.” This shift in subject matter reflects both a new phase in Tomine’s personal life—fatherhood—and an increasingly profound engagement with his characters’ fears, as well as his own.

I spoke with Tomine over the phone this summer, before his book tour for Killing and Dying. His self-deprecating laugh arose every so often, and, depending on the context, seemed to signal anything from embarrassment to wicked delight. It’s the kind of ambivalence that we often find in his characters—and in ourselves, when we observe our reflections on the page.

—Grace Bello for Guernica

Guernica: You created Optic Nerve at the age of sixteen. What was the impetus to make your own comic?

Adrian Tomine: A lot of kids who grow up reading comics spend a lot of time trying to make their own. It’s a natural progression. I’ve seen it in tons of kids, whether or not they have any kind of drawing ability. That was something that I was doing from a really early age. I was doing versions of comics before I could even write words correctly.

The beginning of Optic Nerve was not a clear-cut decision I made: “I’m going to create my own comic!” It was something that I had been doing since I was a little kid, except that, this time, I started trying to write and draw stories about everyday life, rather than superheroes or science fiction.

Guernica: What is your process for creating comics, and how has that evolved over time?

Adrian Tomine: In terms of the physical act of creating it, I guess it’s not that different. I’m still drawing with ink on paper, as opposed to doing it on a computer. But I think there’s a lot of evolution that’s happened in intangible ways, in terms of how I think about the work or how I plan it out.

[Scenes From an Impending Marriage] was created in a sketchbook without any pre-planning. Right before that, I had done the book Shortcomings. Shortcomings was really planned out, and everything was overly considered and agonized over and very precisely drawn. It was a real relief to work in a different way.

I guess I was young and rebellious; I didn’t want to feel controlled by the audience.

Guernica: Speaking of Shortcomings, I know that before you produced that book, a lot of people criticized you for not writing about your identity as a Japanese-American. I wonder whether the book was a retort, or whether this was something that had been brewing for a while.

Adrian Tomine: All of that. For a long time, I bristled at these expectations. It didn’t take long for people to start asking me why [Asian-American identity] wasn’t the focus of my work, or why I had been avoiding it. I think, for a certain period, I was so irritated by that that I went even further and completely avoided anything related to that topic. I guess I was young and rebellious; I didn’t want to feel controlled by the audience.

But at the same time, while I was rebelling in my minor way, I was still accumulating ideas in my mind about what I would do if I ever decided to take on that challenge of writing about Asian-American identity. I think I knew all along that what that would be was not exactly what people were expecting [laughs]. And I was right, because when I finally did the book, it received a pretty mixed reaction, and a fairly negative reaction from the Asian-American segment of my readership.

Guernica: What were the criticisms from Asian-American readers?

Adrian Tomine: Well, I felt good in one way, because there wasn’t a lot of criticism of the craft or the work itself. That was something that I’d struggled with a lot. I think I started getting my work published very prematurely. I really didn’t know what I was doing, but I had already been given a publishing contract with one of the best comics publishers in the world [Drawn & Quarterly]. I had the annoying experience of developing publicly as an artist. I got very used to putting something out there and getting a lot of responses such as, “Ugh, he doesn’t know how to draw the human figure very well,” or “The lettering is sloppy,” or “The inking style is too derivative of these other artists.” There were a lot of valid criticisms about the actual work itself.

So when the focus shifted to the subject matter—I guess I’m sort of a glass-half-full kind of person, because I saw some of these negative reviews and I said, “Hey, they’re not criticizing my inking, they just hate the characters!”

Even after all this time, it’s hard for me to fully grasp, but I think a lot of the criticism had to do with disliking the characters—which, again, I take as something of a compliment. A character has to be somewhat well-written if you are even going to judge it the way you would judge a real-life person, you know? The main character especially was unlikable to a lot of readers. A lot of people came up to me on that book tour and would point at certain bits of dialogue and ask if those were my thoughts, or if they were thoughts of the character that I was making fun of. Maybe because I had done a lot of autobiographical work [in Optic Nerve], there was a lot of curiosity or concern about who was saying these things.

In hindsight, I look at the book and it doesn’t even seem that controversial. But I guess you can’t really second-guess audience reaction. If that was how some people saw it, I had to take that to heart, to a degree.

Guernica: I’m guessing that the negative reaction had something to do with people wanting a role model. It’s not dissimilar to the controversy over Go Set a Watchman. People were really upset that Atticus Finch wasn’t the hero they wanted him to be.

Adrian Tomine: One of the things I also picked up on is, at least in mainstream culture, there isn’t a lot of material on young Asian-Americans, whether it’s in film or literature or comics. So I think if I were of a different background that was more widely represented previously, people would say, “Oh, okay, well, that’s his take on it, but there are twenty other books that might have a more positive outlook.” But I think there was a sense that I was one of the few people from the Asian-American community who had an opportunity to get work out there, and I didn’t use that opportunity in the way they wanted me to.

Guernica: It seems like you’re really conscious of trying to challenge yourself. You did an interview with Hillary Chute, and you said, “The last ten years of my life has been a bit of a struggle for me to…climb onto some next level.” To you, what does it mean to get out of that box?

Adrian Tomine: There’s something about working alone without any editorial input or guidance. The work is completely created in a vacuum. I think I could easily approach my work with: What would be the easiest way to do this story? What would be the simplest way to get this done? There are bad habits that you can get stuck in really easily because no one is looking over your shoulder and saying, “Don’t do another story about a breakup.”

I got really caught up in the idea that what people liked about my work was that I was a young guy who was trying to be cool by writing about young people.

Guernica: Do you mean, for instance, your story “Translated, From the Japanese,” where you avoided showing the characters and relied only on setting and narration? Do you mean challenging yourself in terms of using different modes of storytelling?

Adrian Tomine: There are two different levels there. One was, within the book, I was trying to approach each story differently in some regard. I think I did “Translated, From the Japanese” right after I had done another story that had no narration and was all about dialogue and visual storytelling. So I thought, Is there a way to do the opposite? Can I effectively make comics that are really heavily based on narration?

A lot of it is really about not thinking too much about how the work is going to be received. For a stretch of time, I got really caught up in the idea that what people liked about my work was that I was a young guy who was trying to be cool by writing about young people and a certain kind of Bay Area culture that I was tangentially a part of. I thought, “That’s all I have to offer, and that’s what people like about my work, so I’d better just keep doing that.” To be freed from that was fantastic.

Guernica: I wonder whether getting married and becoming a father has helped you escape that.

Adrian Tomine: Totally. Especially being a father because, if you’re changing diapers and going to the playground, any ambitions of being a cool guy have to fly out the window [laughs]. You don’t have time to keep up with the cool clothes. I don’t go to shows anymore, or any of the things that I used to think were so important when I was younger.

That really encouraged the direction in which I was moving in my writing. Not only am I not well-versed in trends anymore, I don’t really care about them anymore. I thought, Let’s see what happens when I start to think about some of the things that are more at the forefront of my mind right now, at this stage in my life.

I’m sure there’s a small part of the audience who will think, “Ugh, I don’t want to read about some chubby, middle-aged dad! Where are all the cute, young people?” I think if I were going to revisit that, it would be the equivalent of trying to look cool by wearing sunglasses while I’m picking up my kid from kindergarten. It would be so transparent, a pathetic, middle-aged charade.

Guernica: That reminds me of the title story in Killing and Dying. You told The New Yorker that you were drawing from your fears about fatherhood.

Adrian Tomine: That’s true for the whole book. A lot of it has to do with the anxiety of becoming a parent. It took me so long to make the book that I started working on it before my first daughter was born, and now I have two daughters. That, at least subconsciously, is the overarching force throughout the book.

That story came from a couple of places. One was, when I was younger, I attended an open mic comedy event at a café in Berkeley. It was such a horrible, skin-crawling experience that a lot of it is still completely etched into my memory. It’s one of those things that you file away and think, Someday, I’ll find a way to put this in a story.

The other impetus for that story was thinking about what, at that point, were among my greatest fears. One of them was a big, serious topic—the idea of losing your spouse and having to figure out how to live on your own. The other thing was how to be encouraging and supportive of your child when they’re doing something that maybe isn’t that great.

Guernica: I wonder if you have explored—in addition to your relationships with girlfriends or spouses or children—your relationship with your parents.

Adrian Tomine: Killing and Dying is, for me, as much about being a parent as it is about being a child. I think the first impression that a lot of people will have is that my surrogate character in all the stories is the father. As with Shortcomings, it isn’t always so clear-cut. I think that, in a lot of cases with these stories, especially “Killing and Dying’ and “Hortisculpture,” I felt myself in the position of the parent as much as the child.

Guernica: In “Hortisculpture,” the way the child reacts to her father’s failed art is devastating. She goes from being so proud of her father in front of her friend and then feeling hurt and embarrassed by her friend’s ridicule of him.

Adrian Tomine: I don’t know if they’re flip sides of each other, but those two stories have a lot to do with how a family member reacts to someone else’s endeavors. I think that occurs to me as a father as my daughter goes out into the world.

Also, I think it must have been very strange for my parents to have a kid who stayed in his room and drew all the time and, at an early age, was writing these weird, personal stories and putting them out into the world. It was probably odd for them to read my work. It might still be so.

I feel like I’m just a hair’s breadth away from a consensus that what I do is horrible.

Guernica: It is really strange to come of age in that way, where you had a very private life and a very public life at the same time. You were a teenager doing solitary work, yet so many people had access to your innermost hopes and fears, inasmuch as you revealed them in Optic Nerve.

Adrian Tomine: I’ve been so fortunate that, in a lot of cases, the work has been met with a generous response. I feel like I’m just a hair’s breadth away from a consensus that what I do is horrible.

Guernica: When you were younger and just getting started as an artist, were you actually concerned about being cool, or was that an expectation that critics foisted upon you because of your age?

Adrian Tomine: I think most cartoonists are solitary, lonely kids who use their work as a way to try to connect with the world. If I had any other skills that were more performative—if I could have been a musician or an actor—I’m sure I would have pursued that instead in order to get that instant feedback and to hear applause. I think drawing my weird little mini-comics for twenty people in Sacramento was my completely mutated version of that.

Guernica: I know that you moved around a lot. What was that like for you?

Adrian Tomine: My parents got divorced when I was two years old. And mostly because of my mom’s schooling and work obligations [as a psychology professor and therapist], we ended up moving around quite a bit. So I had a lot of experiences of starting up at a new school and leaving friends behind, which is the perfect recipe for staying in your room and practicing drawing.

Guernica: It reminds me a little bit of Dan Clowes’s solitary upbringing.

Adrian Tomine: It’s across the board. All my friends who are cartoonists, we all share stories about moving around a lot. All of us, our parents are divorced, and that had an impact on us. I think, at this point, if I really wanted to create a cartoonist, I would know the steps to take as a parent [laughs].

Guernica: I wonder what it’s like for you to work for The New Yorker, to work with Françoise Mouly. On the one hand, you’re creating graphic novels for Drawn & Quarterly, choosing your own approach and subject matter. But with Françoise, she’s prompting and directing you. Can you tell me a little bit about that process? Did The New Yorker reach out to you?

Adrian Tomine: It’s one of those really significant events in my life, starting to work for The New Yorker. It was one of the few illustration jobs that I actually pursued. I didn’t grow up with The New Yorker in my house, I wasn’t a lifelong reader, but I had become a fan when I was in college, and started digging deep into the history of the magazine and its association with a lot of writers and cartoonists whose work I was discovering. At the time, you could just go into any used bookstore and find these great collections of cartoons from the early days of The New Yorker. I was prone to these obsessional phases, and I was really interested in the magazine—the present-day version, and its history.

I was living in California at the time, and I went to visit a friend in New York. I decided that I was going to try to send my work to The New Yorker. A lot of times, I’ll meet a young art school student, and the only thing they want to know about is how to get into The New Yorker. In telling the story about how I did it, I realized that almost every step of it is completely extinct at this point.

I went to New York, and I made a physical portfolio with tear sheets of my illustrations from other magazines. I put it in a folder. I printed out my name and my fax number on the outside of this folder. I got out my friend’s phone book and looked up The New Yorker in the phone book, took a cab to that address, and walked in without any problems from security. I went up to The New Yorker office and asked the receptionist if I could leave my portfolio there. He said, “Okay.” Eventually, somehow, it made it into the hands of an art director there named Chris Curry. I was back in California, she gave me a call, and she gave me my first assignment.

Guernica: I’m curious who, among the newer cartoonists, is doing work that you’re really intrigued by.

Adrian Tomine: In the past, if there was one new cartoonist who showed up each year and started producing something of note, you would look at it and say either “It sucks” or “It’s great.” You would know exactly the influences that that person was coming from. Now, it’s totally different, and it’s opened up this whole new part of my brain where I can look at a new cartoonist’s work and have a totally enthusiastic but mixed response [laughs]. I think that’s much more common in other art forms: you could look at an Antonioni film and say, “Oh, it’s not exactly my thing, but, man, that was really impressive.” That’s definitely a new development for me with comics.

I don’t want to dodge the question. There are quite a few. Like I said, there used to just be one new cartoonist per year, and everyone would have their opinion on him—and it was always a him.

There’s Michael DeForge… Who else? There are many artists, all of whom are more ambitious, original, and prolific than me: Jon McNaught, Ethan Rilly, Jillian Tamaki, Nick Maandag, GG, Kate Beaton, Nick Drnaso, Simon Hanselmann, Leslie Stein. I don’t know if Vanessa Davis would count as a new artist, because she’s been at it for quite a while, but she might be new to some people.

Who or what a cartoonist is in America now can mean so many things.

Guernica: You were saying that what you did to advance your career would be considered so anachronistic now. What’s your take on the modern comics landscape, in the age of Tumblr and webcomics?

Adrian Tomine: I feel like it had so many years of stagnation. The last ten years—and even the last few years—have just been mind-blowing, in terms of the progress and evolution that has happened. I think one of the real turning points was when certain artists whom I had been a fan of for a long time produced work that was so good and so visible for the first time that it really started to change the whole North American perception of what comics could be. I give a lot of credit to Chris Ware’s Jimmy Corrigan and Dan Clowes’s David Boring and Ghost World. I think that really got the ball rolling.

Around the same time, there were a lot of people who were about my age who had grown up reading comics, and were especially fans of alternative or underground comics, and they had become editors at magazines and art directors at ad agencies. They were in a position to start promoting artists’ work. I think that not only made comics more socially acceptable, especially in America, but they also really started to help create an atmosphere where there was at least a slight possibility that you could make it a viable career and make some money off of it, as opposed to making it a pure passion project that you would do when you weren’t delivering mail or something like that.

When those floodgates opened up, suddenly a much broader range of talented people in the world started thinking about comics as a possible venue for expressing themselves. Who or what a cartoonist is in America now can mean so many things.

Guernica: Who inspired you when you were first starting to get into comics?

Adrian Tomine: Like most of my peers, I grew up reading really bad mainstream superhero comics because, in the ’70s and ’80s, that was really all that was available to us. For me, the biggest turning point was finding Love and Rockets [the influential comics series by the Hernandez brothers], which led to a whole lot of other great alternative comics. It was just perfect timing that I stumbled upon that stuff.

Prior to seeing Love and Rockets, I really thought of comics in the way that a lot of people in the world still do, which is that they think of it as being intrinsically tied to certain genres. When you think of comic books, you think of superheroes, and that’s kind of how I thought of it. I thought, I’m not really reading these comics that I’m buying anymore; I have no interest in them. I’m just done with comics. And then seeing Jaime and Gilbert Hernandez’s work in particular was a real eye-opener. Again, it’s now common sense to a lot of people, but they showed that comics were just a way of telling stories, and those stories could be about anything.