People spend their time crying over the loss of Christ, and they don’t really think about the pleasures in life. One of the things I’ve come to see is that people do have a limited time span on earth. Knowing this, it would be well to fill those hours as pleasurably as possible, playing music, getting along with people, eating well, drinking, screwing, enjoying the pleasure of one’s company and helping others do the same.

—Les Blank, “A Well Spent Life: Les Blank’s Celebrations on Film,” by Andrew Horton, Film Quarterly, 1982

Dry Wood, Les Blank’s 1973 documentary about Creole life and music, throws the viewer headfirst into unfamiliar, almost bizarre, scenes of backwoods theater. It opens with a troupe of revelers costumed in cone hats, clown masks, and frilled jumpsuits, chasing a rooster around a yard. The camera follows their pickup trucks down a country road and into a gas station’s dirt parking lot, where they tip back handles of liquor and dance around while a fiddler plays. Someone throws a handful of pocket change up into the air; they go chasing after that, too.

This sequence of rag-tag Mardi Gras—like Rabelais with tractors and Budweiser—unfolds mostly on its own. No voiceover narrator or talking head chimes in to explain what we’re seeing—there are only the subjects themselves, accompanied by festive strains of zydeco music. Dry Wood becomes a brief immersion in that folk genre, a film that weaves the music into scenes of daily life—especially of celebration—for a dynamic, appreciative portrait of a longstanding American micro-culture.

In short, it’s vintage Blank. Blank’s single best-known film is Burden of Dreams, a chronicle of Werner Herzog’s fraught production of Fitzcarraldo in the Peruvian Amazon. As remarkable as that film is, it’s Blank’s music-driven film-poems of the American South in which his singular blend of zestfulness and observant naturalism truly comes alive.

It is often said that non-fiction filmmaking is having a moment.

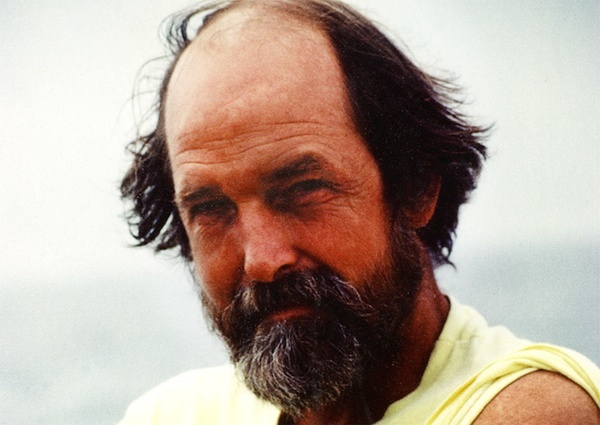

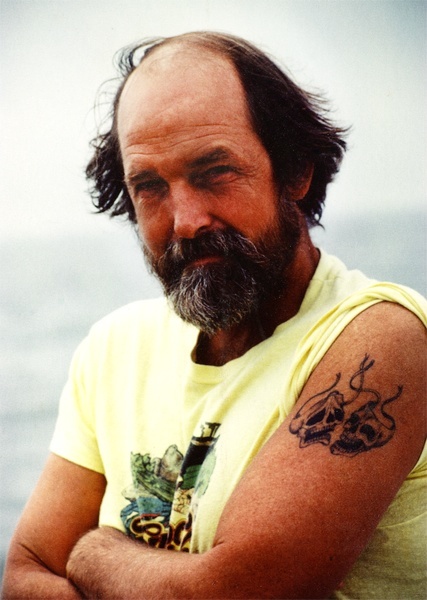

Blank, who died in 2013, made some forty documentaries. (Criterion has just re-released fourteen of them, along with selected outtakes and interviews, as part of a three-disc set.) He had a watchful, slow-moving presence that moved Herzog, a longtime friend, to characterize him as a “Southern bullfrog.” By his own admission a shy man, Blank populated his tiny film crews with collaborators, such as longtime co-editor Maureen Gosling, who, as he told MoMA’s Sally Berger in 2011, would be “more at ease in a social situation.”

And yet his films depict communal social life at its most affirmative and unselfconscious. This was the closest thing to an agenda that Blank brought with him on his trips into tight-knit Creole, Cajun, Southern black, Appalachian, and Polish-American communities. He filmed casual interviews with his subjects wherever they felt most comfortable. His shoots were often about waiting—day after day, trying not to burn through too many feet of expensive film—for moments that Gosling describes in an interview included in the Criterion set as “anytime people were expressing themselves authentically.” Blank’s camera is alert, to be sure, but often more expressive than the shots themselves is his editing. (In a 2010 interview with CineSource magazine, he credited the Serbian-American experimental filmmaker Slavko Vorkapic as a major influence.)

There is a paradox to these films: they are celebrations of the moment, and yet also convey a yearning for simpler times.

The editing is supremely artful and guided entirely by feeling. A close-up of guitar strings dissolves into a panning shot of barbed wire twined with purple flowers; the tangerine surface of a river at sunset expands and contracts like an accordion bellows. There is no particular narrative or rhetorical linearity in Blank’s Southern films. They are, instead, poems about people who, despite the implied difficulties of their situation, seem enviably of a piece with their human and natural surroundings.

There is a paradox to these films: they are celebrations of the moment, and yet also convey a yearning for simpler times. Blank has, correctly, been called a romantic. His films offer an escape from the banality and glitz, the falsity and commercialism of contemporary life. The discrimination and other hardships plaguing these communities emerge only in bluesy melodies, or song lyrics, or second-hand tales, or the faraway gaze of Creole accordion virtuoso Clifton Chenier’s 108-year-old grandmother. The suffering of a people is stitched into their longstanding folk tradition, rather than discussed openly.

I say longstanding—but not necessarily ongoing, for these micro-cultures were already fading when Blank filmed them. (Tommy Jarrell, the aging fiddler who was the main subject of 1983’s Sprout Wings and Fly, pressed Blank to finish editing so that he could see the film before he died.) Two or three generations later, the ’80s resurgence in Cajun music notwithstanding, they have no doubt receded ever deeper into history. Is it not all the more valuable, then, that Blank’s films emphasize their difference and vibrancy? If Blank “did not make a film about the Cajuns, he made a film about what he found unusual and exciting and different about the Cajuns,” as Cajun folklorist Barry Jean Ancelet wrote of Spend It All (1971). Then so much the better—for posterity, and also, perhaps it is not too much of a stretch to say, for those Cajuns and their grandchildren.

It is often said that nonfiction filmmaking is having a moment. The early twenty-first century has brought smash hits like Michael Moore’s Fahrenheit 9/11, An Inconvenient Truth, and March of the Penguins. Advances in technology have allowed some documentaries to encroach on the territory so long monopolized by Hollywood blockbusters, and film festival lineups are thick with docs. All this is undoubtedly for the good. But we should also ask: How many interesting things are being done with the form itself? Is it not the art of the documentary that is booming, so much as visual nonfiction storytelling?

To be sure, visual storytelling is no easy craft to master. But too often, nonfiction film remains that—a craft, which is to say a form of expression stuck in a blandly narrative or didactic or rhetorical mode. Moreover, the clichés of the mainstream documentary are easily co-opted in service of an outside agenda, whether that of an admirable social cause or that of a corporate initiative, like “Facebook Stories.” And when it comes to aesthetics and depth, the bar seems to be considerably lower for documentaries than for scripted films. In The A.V. Club magazine last year, veteran critic Scott Tobias devoted an entire essay to this imbalance, arguing that American nonfiction film is too often “a form of cinematic activism where art is of secondary concern.”

Similar constraints apply to the ethnographic film, a documentary subgenre that Blank brought to the American backyard, so to speak. Before his artful examinations of the Texas-Louisiana music belt, there was Nanook of the North, Robert Flaherty’s admiring film on Inuits, and The Hunters, John Marshall’s romanticized take on Kalahari tribesmen. Blank acknowledged both as important predecessors. But for various reasons, from the politics of filming minority groups to increased urbanization and the homogenization of world cultures, the focus of the so-called ethnographic genre seems to have shifted—for good and for bad, no doubt—from the (appealingly) isolated outsider to the (unjustly) excluded or disadvantaged one.

The lineup at this year’s Margaret Mead Film Festival—the American Museum of Natural History’s annual presentation of film works focusing on anthropological themes—is indicative of this development. While the program features films set in less-than-fully-Westernized places and cultures, it also contains one that “examines the daily issues Mexico City faces managing its water, reminding us that sustainability is deeply linked to social justice.” There is a feature-length film on a New York activist for the disabled, and a profile of a Jewish teenager from New York who “begin[s] to piece together a big family secret, and her own racial identity.”

Rather than advocate overtly on behalf of his subjects, his films evince a hunger to connect with them.

In the grand scheme of things, of course, Blank’s politics align with those of documentaries like these. As he once explained, “I try to show that the people in my films are human beings who have just as much right to be on this earth as anybody else. Maybe more right.” And yet Blank’s films, which emphatically choose rejoicing over moralizing, sensation over argument, anthropology over sociology, could hardly be more different. Rather than advocate overtly on behalf of his subjects, his films evince a hunger to connect with them. They adhere above all to the pleasure principle, and the Southern ones in particular reflect Blank’s ongoing quest for something I don’t think it is trivializing to describe as flavor.

Blank grew up in Tampa, the son of a real-estate developer. Uninspired by his white-suburban surroundings, he was drawn at an early age to rowdy barn dances and tailgates, and to the Cuban and African-American cultures around him. His own community did not exactly encourage these interests, but as he later explained in a 1986 television interview filmed by UCB, “The more I was told these people are beneath me, and that I should stay away from them or that they were dirty or ignorant or trashy, the more curious I became.”

Blank often mentioned Ingmar Bergman’s The Seventh Seal as the movie that made him want to become a filmmaker. But during an unreleased interview that’s included in the Criterion set, he recalls the first time he saw “El Jaleo,” John Singer Sargent’s painting of a flamenco dancer, at Boston’s Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum. “It was something about this kind of art, in which people’s whole being was thrust into it—where art and life intersect and everything becomes expressing yourself,” Blank says. As he was never one to go on at length about himself or his approach to film, one is tempted to treat this revelation as a sort of “Rosebud” moment.

The people he films are in need of another helping of gumbo, not salvation.

In Blank’s Garlic Is As Good As Ten Mothers (1980), a chef describes the underuse—and, indeed, stigma—of garlic in this country as a regrettable consequence of “the American-Puritan-Anglo thing.” This, in a way, gets to the heart of the matter as much as the Sargent painting. Blank was, after all, a product of the ’60s counterculture, a movement that rebelled against a dominant ethos of propriety and self-denial. (His early film God Respects Us When We Work, But Loves Us When We Dance, documented the famous 1967 Elysian Park love-in.) Getting away from the “American-Puritan-Anglo thing” meant turning the sinful into the celebrated. Blank made Gap-Toothed Women (1987) after a conversation with a Tulane English professor about Chaucer’s lusty Wife of Bath. His titles alone—Hot Pepper or Yum Yum Yum—are an assault on the idea of moderation. The people he films are in need of another helping of gumbo, not salvation, and attempting to “educate” or proselytize to the viewer in this context would serve more than anything as a return to the Sunday school that Blank was so eager to flee for the honky-tonks.

Within the strict limits of politeness that he set upon himself, Blank’s films attempted to knock down the wall between filmmaker and subject. This was not always easy, in logistical terms alone. Police in Louisiana gave him trouble for living among blacks and Creoles. Higher-profile subjects like Chenier and the blues guitarist Lightnin’ Hopkins had been exploited before by white visitors and their recording equipment, and Blank (with good reason, surely) had to pay them to participate.

In the end, though, his camera got in the mix—and he did, too. To me, it is not vanity but something much more endearing that prompted this timid personality to insert brief shots of himself into his Southern films, enjoying watermelon or boiled crawfish with his subjects.

In the Southern films, Blank’s camera-narrator consistently sits in observation rather than in judgment. But his vision does seem (to me, at least) to lapse at one point in Burden of Dreams. This happens during a scene in which the actor Klaus Kinski, playing Fitzcarraldo, refuses to drink masato, a cassava home brew fermented with saliva that is offered to him by his Indian hosts. The narrator, in a flat tone, explains that the temperamental Kinski fears “contamination.” If there is one unpardonable sin in Blank’s film universe, then that is it.

Darrell Hartman is a writer based in New York and the editor/co-founder of the website Jungles in Paris.

To contact Guernica or Darrell Hartman, please write here.