The image I remember best was a horizontal frame of a lonesome little graveyard where thin, moss-covered tombstones stood askew in a field of glowing poppies. Above them a majestic oak spread its branches like a gnarled fan. The photograph was taken in 1953, just before the town was razed to make way for the Monticello Dam.

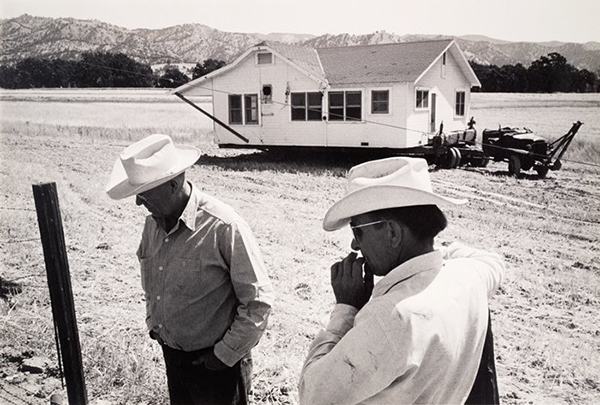

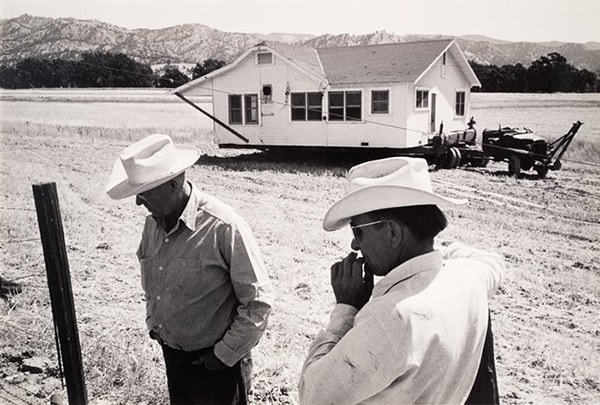

I came upon the photograph in the spring of 2007 in a tony boutique hotel in Santa Monica, California. The hotel is stationed alongside the iconic Santa Monica pier, a raucous, all-day carnival that is the diametric Californian opposite of the oaken rangelands that still ramble where the town of Monticello used to be. I was there with my family and, one afternoon in the lobby, my mother and I sipped tea and lazily pawed through Death of a Valley, a series of photographs of Monticello by Dorothea Lange and Pirkle Jones. At first it was just the images of bygone, quotidian California that drew us in—a man behind a switchboard at the general store, a well-dressed family attending church on Sunday, a woman slicing onions and wiping away tears at her kitchen table, a worker holding up a wooden crate of just-harvested grapes. But the images grew more sinister with every page: a horse galloping madly through a burned field, a house set on fire, a giant tractor with its big metal rake like a wicked mouth traversing the torn-up valley and kicking up a cloud of dust where the plants used to grow. A second photograph of the town cemetery showed rows of clean-cut holes where the bodies had been exhumed, no more towering oak, no more headstones, just those coffin-shaped hollows and the mounds of dirt heaped beside them.

The introduction to the book explained what had happened to Monticello: identifying the need for more water in Northern California, the US Bureau of Reclamation—the federal agency charged with “managing water and power in the West,” in part by laying claim to privately held land—decided to dam the steady-flowing Putah Creek, which was more like a midsize river running through the Berryessa Valley, in Napa County to provide irrigation for neighboring Solano County. Twenty percent of the water was to be devoted to human consumption, 80 percent to agriculture to feed the people flooding into California.

“Every month 30,000 people are coming to California,” said then–California Governor Earl Warren in 1953 to justify building the dam, “and not one of them brings a gallon of water.”

From this need for water, the so-called Solano Project was born. The townspeople fought against the dam, picketing and protesting and writing letters to their representatives. “We object to the Monticello Dam because it is a project…that will destroy our homes, our land, our business enterprises, and our way of making a living” read the opposing statements during the California Water Conference of 1945. “We cannot see any economy in a project that will destroy forever a large part of one county attempting to benefit a part of another when we know that by careful planning the project can be set up to benefit all concerned.” But less than 500 people lived in Monticello, and the government reasoned that the sacrifice of their little town would feed and provide drinking water for many thousands. “It is the solemn duty of our generation to plan wisely for the best use for all purposes of every drop of water,” said Governor Warren. Like a coming rainstorm, the Solano Project couldn’t be stopped. Monticello was to be drowned.

Lange sold the photo essay to Life magazine in the year leading up to the drowning and then approached Jones about working on it with her. (In the end Life opted, perhaps because of the project’s existential gloominess, not to publish it. Aperture ran Death of a Valley instead.) Flipping through the book that day in Santa Monica was like stepping among tombstones: we watched, much as the photographers and the Monticellans had, the town’s slow defeat. “Visible changes came slowly and quietly. There was packing, selling, moving. Families disappeared, melting away, emptying the valley. There were sounds of ripping wood for salvage amid the buzz of insects and smell of tarweed in the air, as it had always been.”

California’s history is a story of thirst. My mother grew up in a farm community where talk of water never stopped.

My mother was born the year the Solano Project was approved. She grew up just over the ridge from Monticello, amid the same buzz of insects and the same smell of tarweed. She played in the shadows of tangled oaks just like the Monticellans had. Her family of nine, descendants of pioneers who’d done their own ravaging and displacing of indigenous peoples and their land, grazed cattle and farmed almonds near the Cache Creek. Their farmhouse was sold off and torn down after my grandmother died in 1976, seven years before I was born. And a massive casino was built just a few miles down the road, changing the Capay Valley for good. Having lived through so much building and tearing down, there’s something about both the razing and the excavation of California that fascinate my mother and, because I am her daughter, captivates me, too.

But we were also magnetized by this book because, as Californians, we are obsessed with water. California’s history is a story of thirst. My mother grew up in a farm community where talk of water never stopped—who had it, who didn’t, how to get it, how much it cost, why Los Angeles got away with siphoning off all the good water that belonged to the people up north. Her neighbor, Joe, was a for-hire water witch whom people paid to come onto their property with his forked stick. “Drill here,” he’d say, and people dug their wells.

I grew up during the drought in the nineties. Adults asked us to limit our showers to three minutes, and clowns on public television told children how to save water while brushing their teeth. It was so dry that in 1991, when I was in the first grade, a fire ripped through the parched hillsides of Oakland and my cousins, who lived there, were forced to evacuate to our house in San Francisco. They packed their car with pets and family photographs and changes of clothing in case their house burned.

We’ve now entered another period of drought that, according to many scientists, may not end for decades. In April, California’s snowpack was only 5 percent of its normal average for that time of year; the previous record low was 25 percent of average, in 1950. Snowpack feeds rivers, like the Putah Creek, which irrigate fields and fill reservoirs. And when it snows in the Sierras it usually rains in the valley, and that rain sates our crops and our gardens and our forests and our reservoirs and makes it less likely that our hills, come summertime, will burn.

Last year, 2014, was the warmest and third-driest of any year of the 119 on record. In early 2014, California Governor Jerry Brown declared a statewide water emergency. My aunt, a cattle rancher in the Sacramento River Delta, had to spend an unanticipated $50,000 on feed because her free-range cows could find nothing to eat in the desiccated hillsides. Because of limited grazing land, farmers are selling their cattle sooner, and keeping smaller herds. This summer, even more fires tore through the foothills—throughout the state, 5,496 fires burned more than 300,000 acres, compared to an average of 100,000 acres burned annually over the past five years. Just last month, a massive forest fire narrowly missed my aunt’s farm.

Despite California’s status as the national fruit basket, rainwater has never been enough to sustain the massive cash crops—an industry that accounts for half of all the fruits, nuts, and vegetables grown in the United States, 70 percent of the fruits sold and eaten in stores countrywide, and 55 percent of the vegetables bought and prepared in restaurants and homes. Peaches, avocados, almonds, lettuces, melons, broccoli, pomegranates—we have it all, and so much of it, but at a great and hidden cost. The state’s agricultural system relies on the diminishing reservoirs like Lake Berryessa and the state’s increasingly depleted groundwater. Now, irrigation is so expensive that this year and last, some farmers let their fields go fallow. This means less work for farmworkers, less income for ranchers, higher prices at the farmers’ markets and grocery stores. A strong El Nino storm system is predicted this winter, and if it reaches us up north it will bring some relief, but, scientists say, not nearly enough to pull us out of a long-term crisis.

It’s as simple as this: our current water habits are unsustainable. California is a great, slick hustler at the card table, bluffing a myth of plenty while holding tight the fan of truth: we are now, and have been for the entirety of modern history, running out of water.

Berryessa is an hour and a half from where I live in Berkeley, and as I snaked north on the windy, near-empty roads, I felt like I was traveling back in time to solve some kind of mystery: What had become of that drowned town, and what might we do different this thirsty time around? Would we dam another river, submerge another town? In desperate times like these, is it ethical to sacrifice a place like Monticello?

Despite the fact that we were in the thick of the drought, there had been a few days of rain the previous month. Even though we were only at about 15 percent of average precipitation, it had been just enough to wash the hills in green. Legions of California oak trees with knotted branches hung low over the roadway, creating a kind of tunnel through which I drove. The trees sifted the sunshine, casting gyrating shadows. I felt I was moving through the California myth itself: all this green belying our thirst, this story of fertility and abundance alive and well, and me a part of it.

Then, out of nowhere, droplets of rain began to ping against my windshield. They fell heavier and heavier until I was moving in a full-on downpour. I turned my windshield wipers up as high as they could go. After a few minutes, the water stopped and the sky opened back up into blue, like the rain had never happened, and part of me wondered if I had maybe dreamed it up for all my worry about the drought.

I turned off the main road and slid into the valley, past the boat ramps and camper facilities and the small general store advertising bait and gas. An arrow pointed to the relocated Monticello cemetery, the place where they’d reinterred the town’s bodies. I followed it. It was the only thing left of Monticello besides stories and photographs and a few descendants scattered throughout the state. But what I found was nothing special: a fenced-in collection of newer-looking headstones on a manicured hillside. The gate was locked, and though I knew I was looking at the graves from the Death of a Valley pictures, the spirit of those photographs was long gone, languishing, I presumed, at the bottom of the nearby lake. As the road evened out the Lake Berryessa visitor center appeared, and I parked my car. Mine was the only car in the lot.

Inside, I was greeted by a ranger, a tall, good-looking, but self-effacing, gentleman in his forties named Chris. I told him I was writing about Monticello.

“So tell me,” I asked, “what’s down there?” For years, I’d imagined barns, former stables, and church steeples hovering in the long, slow stillness of the deep.

“Oh, nothing,” he said, shaking his head. “They scoured, they scraped the valley,” he said, as if remembering firsthand the way the big mechanical cats came and tore it all down. The Bureau of Reclamation had learned its lessons the hard way from dammed lakes back east, where bits of old houses and churches and other drowned relics would occasionally pop up to the surface. “These were terrible boating hazards,” said Chris. By the end, the Berryessa Valley “was like an empty bathtub.”

Since 1957, Monticello has been rubble and ash.

They’d so eviscerated all ecological habitat that when they tried to populate the newly drawn lake with bass for sport fishing, the fish all died; they had nowhere to lay their eggs. Local bass fishermen took to cementing unsold Christmas trees into buckets and dropping them to the bottom of the lake to create a more hospitable place for fish to thrive.

Chris pointed out a photograph on the visitor center’s wall of Governor Warren, victorious and beaming, perched on one of the first demolition tractors to enter the valley. The edict read:

The only thing the Solano Project didn’t demolish, Chris told me, was a historic bridge, the largest masonry bridge west of the Rockies, which was comprised of three stone sections of seventy feet each.

I looked out at the lake, and, much as it had been the enemy of the Monticellans, it was beautiful—shimmering and surrounded by gently sloping hills.

There’s a poetic justice to the displacement of the Monticellans in that California, just as much as it is a story of water, is also a story of buried histories. Before the American settlers came, Monticello was a Spanish hacienda owned by the Berelleza brothers, a remnant of a Spanish land grant honored by the US government. And before that, it was a prosperous Wintun village that had been, like the homes of most native tribes, destroyed at the hands of the Europeans. On the title page of Death of a Valley: “The new California is coming in with a roar…” The Wintun must have said nearly the same thing.

So perhaps another form of poetic justice, or cruel irony, depending on who you are and how you care to look at things, is the fact that Berryessa itself is now drying up. The lake hasn’t been at its regular depth since 2006, and its banks have been steadily receding. Despite a December storm that helped the lake climb eight feet over the course of just a few days, in February Berryessa was still twenty-eight feet shy of normal—with no rain in sight. “Unless we have a miracle March,” said Chris, the water line will only continue to drop. March came and went with no miracles.

I looked out at the lake, and, much as it had been the enemy of the Monticellans, it was beautiful—shimmering and surrounded by gently sloping hills. The idea had been that Solano County would get all the diverted water, and Lake Berryessa would become a tourist destination and bring bucketloads of cash Napa’s way. But in the end, Lake Berryessa wasn’t the viable year-round destination they’d hoped and the drought was making things worse. “Tourism is suffering,” said Chris. He’d been here for ten years and, though he loved the area and knew its contours and history better than anyone, was preparing for a new post east of Berryessa in the foothills near Angel’s Camp.

Years ago, Chris had tried to secure permission to display copies of the Death of a Valley photographs in the small visitor center. He’d met Pirkle Jones at a retrospective of the photographer’s work in Sacramento about a year before Jones died (Lange died in 1965). They got to talking, and the ranger asked Jones if he might consider allowing the Parks Service to install an exhibit. “He just felt like his subjects were so angry at the Solano Project that to give these photographs to the visitor’s center would be betraying the trust they put in him all those years ago.”

I was hoping that they’d have a copy of Death of a Valley at the visitor center, but no such luck. It’s an elusive book. I’d tried to buy it online, but it was listed at $400, and then not at all (my mom even tried to go back to swipe it from that hotel years later, but by then it was gone, and the hotel staff knew nothing of it). I finally tracked down the book in the UC Davis Special Collections Library and a few days, after visiting Berryessa, went to have a look.

As I eagerly turned the pages in the reading room, I realized that I hadn’t remembered much of the book at all. Most of the images I didn’t recall. And there were images I recalled that, it turned out, I had invented. There was no scene of a family sitting in church pews and dressed in their Sunday best, and no scene of a woman cutting onions and wiping tears at her kitchen table—images upon whose veracity I would have bet the mortgage. I realized with some alarm that I’d been so taken with the story of Monticello’s undoing and its uncanny documentation that I’d filled the scoured hole of the Berryessa Valley, a place I’d never even been, with conjured moments, falsehoods. Even the book itself was smaller than I remembered, with a much thinner spine.

Dreams are the stuff we sell: Hollywood, sparkling beaches, teeming crops, flowing wine, shimmering gold, technological innovation, everything abundant and larger than life.

But perhaps my fictions, too, were appropriate, because California has always been about impossible dreams. Dreams are the stuff we sell: Hollywood, sparkling beaches, teeming crops, flowing wine, shimmering gold, technological innovation, everything abundant and larger than life. On the cover of Pirkle Jones’s California Photographs is a smiling migrant worker in Monticello holding a crate overflowing with newly picked grapes. You’d have no idea that these were the last of the Berryessa grape harvest. In California, we’re racing to catch up with our own ambitions. And as we suck our groundwater dry, we are operating on borrowed time.

One photograph that I remembered well, one that I hadn’t invented, is of the manager of the Mackenzie general store, donning a cowboy hat and hunched over a table spread with paperwork. He’s settling up the month’s accounts in a neatly lined ledger. What more futile act, to measure the gains and losses of a store that’s set to be torn down? And yet the accountant toils over his accounts just the same, the farmer picks the grapes, families visit their dead as long as the cemetery is still there, we visit the shimmering lake to admire what’s left of it.

The Monticello Dam was finished in 1957 and, like a giant, empty tank, the scoured and scraped valley began to fill with water.

When my mother was a child, her father would load her and the six other kids into the pickup truck and drive them down to see the Monticello Dam. The water here didn’t reach their farm, but the bigness of it all drew them just the same. They’d press their faces up against the chain-link and watch the water suck into the glory-hole, a massive concrete spillway twenty-two meters in diameter, over the lips of which thousands of gallons of water tumbled each second and dumped into the Putah Creek several hundred feet below. My mother would watch the hole with that childhood terror of the vast, worrying about boats or swimmers who might be sucked in. Her family would linger there for a while, the boys throwing stones into the running creek, and then they’d load up and leave. The world was changing; California was changing. It was happening in a quick-running current and all right before their eyes.

The day I visited Monticello, I decided to take a different way out of the valley, and headed for another stop in Sacramento. This southern route would take me past the dam. I stopped along the bridge where my mother and grandfather and aunts and uncles used to pull over, looking out onto the great, streaked bowl that held Lake Berryessa in place. But beneath me, the Putah Creek wasn’t more than a dribble, and above the dam, the glory-hole was bone-dry. Without much water, the hulking apparatus felt eerie and forlorn. There was an abandoned quality about this wintertime Berryessa, I realized; the dam itself was even more of a sad ruin than the razed town of Monticello. I drove on and the road took me away from the man-made dam and back toward what nature had built: bushels of heather, green grasses both a hope and a lie, a few wildflowers speckling the valley. The road took another bend to offer one last glimpse of the lusterless Monticello Dam standing tall against the horizon. I watched the sky for another phantom rainstorm, but the February day just glistened on.