The Bodies

We were not alarmed when the dead began to show up at their own funerals. First Uncle Lionel Batiste, drummer for the Treme Brass Band, appeared—not an apparition—in the flesh, leaning on his cane, his watch as usual around his palm because, as he always said, he liked to have time on his hands. Then it was the socialite Mickey Easterling on a park bench in the auditorium, feather boa around her shoulders, BITCH brooch on her breast, holding champagne in one hand and a cigarette in another—like Baron Samdi himself, in whiteface and drag. Miriam “Mae Mae” Burbank had her drink (Busch) and smoke (Kools) too, as she sat at her dining room table at the funeral parlor while a disco ball spun.

“I know she’s happy with how she’s looking, everybody else is,” her niece told the TV crew. “She gets down.”

The news clip is tagged “Regular Lady Gets Awesome Funeral”—even though she was no jazz musician or socialite, the TV crews came for Mae Mae as they had come for Mickey and Uncle Lionel. The camera lingered on her sewn-shut lips, the reflections of colored lights in her dark glasses, the uncomfortable dancing of people who know they’re being filmed.

“When I walked in, I felt like I was in her house,” her sister told the local TV station, throwing her hand at the orchids by the bar cart, Mae Mae’s beer glass half-full. “I don’t hurt so much, because it’s more her. It’s like she’s not dead. It’s not like a funeral. It’s like she’s just in the room with us.”

This was why the reporters had come: we are not used to having the dead in the room with us, not anymore. “There used to be no house, hardly a room, in which someone had not once died,” Walter Benjamin wrote in 1936, closer to that death-haunted time, but now, we “live in rooms that have never been touched by death, dry dwellers of eternity.” Even the open caskets of my childhood—the waxy rouged faces of great-aunts and -uncles (congenitally Catholic, I had twenty-three) enveloped in the smell of embalming and lilies—are increasingly rare.

The New York Times ran its piece on this “trend” under the headline “Rite of the Sitting Dead,” and a light tone of mockery runs through most of the media coverage of these funerals. The journalists depict the funeral directors they interview as irreverent businessmen, the Barnums and Baileys of some kind of Circus of the Dead—“gleefully” checking text messages from “haters” while making jokes about thinking “out of the box.” But the reporters admit that “even” the directors have their limits, unlike the men and women who call to plan their own funerals, asking to be remembered as someone who stood over a cooking pot, someone who loved the beach. “Even Miss Rodríguez,” begins the last paragraph of the Times article, “said she has had to refuse a few suggestions that she found distasteful…. She will not, for example, do a wake with someone in a swimsuit, she said.”

Taste is about what is proper—what is fitting, comfortable, polite. It is also about what is beautiful—which, in a pure aesthetics, according to Keats at least, can mean what is necessary and true, or, class-inflected, can be drawn according to the whims of the powerful, to maintain the aesthetic supremacy of the upper class. Good taste, then, is often defined according to luxury.

New Orleans, the media want you to know, has always put the “fun” in funeral, but the reporters don’t bother to investigate why that is, what celebration in the face of death might mean in a culture that has known slavery and yellow fever, a murder rate north of Medellin’s, a hundred-year flood. Nor do they examine the prevailing norms of funeral customs in the West—customs borne out of time and resources and wealth, the luxuries of hospitals and Doppler radar and drone wars, the ability to leave the dirty work of caring for the dead to others, the choice to act as though the dead and dying do not exist in the same world we do.

At nice funerals now in the West, we listen to poetry, sign our names to poster-sized photographs of the dead as they smile beside a lake in the sun, watch as an urn is placed in a marble box or a wooden box is covered in a sheet of Astroturf, eat cookies, kiss cheeks in a long receiving line. Sometimes we hold handfuls of ash, sprinkle them on water or fields, but usually it is cleaner than that and there is no trace of the body at all, as if this person we are mourning had been assumed into heaven on a cloud.

In all of this, though, aren’t we turning away from something—from the body, surely, but possibly also from death itself? We tend to think there is something horrific, ugly, about watching a body burn, about shoveling dirt over a casket, but this is also true: eventually all bodies decompose. Either fire consumes them, or worms do. While someone else zips the bag, closes the ambulance doors, presses the button that carries the casket into the fire, we miss the very moment when, Benjamin again, “real life…first assumes transmissible form.” Despite the fact that we speak of it often, we have no innate sense of our mortality: it is something learned. The corpse gives us our understanding of death. Staring at the papery eyelids or holding the limp body, we know suddenly and fully what was—what we call human is what is gone.

In “the collective act of repression symbolized by the concealment of our dead”—as Karl Ove Knausgaard has it—is it our own mortality that we are trying not to see? Knausgaard writes in the first movement of My Struggle:

There are few things that arouse in us greater distaste than to see a human being caught up in [death], at least if we are to judge by the efforts we make to keep corpses out of sight. In larger hospitals, they are not only hidden away in discrete, inaccessible rooms, even the pathways there are concealed, with their own elevators and basement corridors, and should you stumble upon one of them, the dead bodies being wheeled by are always covered…. The homeless who freeze to death on benches and in doorways, the suicidals who jump off high buildings and bridges, elderly women who fall down staircases, traffic victims trapped in wrecked cars, the young man who, in a drunken stupor, falls into the lake after a night on the town, the small girl who ends up under the wheel of a bus, why all this haste to remove them from the public eye? Decency?… Even [an] hour in the snow is unthinkable. A town that does not keep its dead out of sight…is not a town but a hell.

But necessity sometimes overrides propriety. In New Orleans we’ve known such a hell.

In the flooding that followed Hurricane Katrina, bodies floated in the streets and slumped in folding chairs in the sun. They lay on street corners for days, and cameramen took their pictures while National Guardsmen, policemen, other journalists passed them by. “That’s where the dead guy was,” my friend points out as we pass the Circle Food where the I-10 peels off of N. Claiborne, and I see again the water rippling under the overpass, the dead guy floating in his ballooning shirt, face down. Like a dog, we say. Left in the street like a dog.

What does it say, then, when we the living fail to care for the bodies of the human dead? What does it say about our humanity, and about what we think of theirs?

The care we owe bodies is reliant on our understanding of their humanity. Humans do not die like dogs, because, unlike dogs, we live in death’s anticipation. Our mythologies are clear on this. “You are dust,” God says as he expels Eve and Adam, “and to dust you will return”—they were animals in the garden, in their ignorance, and now they are men. Knowing that we will die, we concern ourselves about what will happen afterwards, to our bodies, which we, intuiting a truth perhaps belied by talk of souls, find it difficult to separate from our conception of ourselves. What does it say, then, when we the living fail to care for the bodies of the human dead? What does it say about our humanity, and about what we think of theirs?

From Louisiana’s Code Noir of 1724, XI: Masters shall have their Christian slaves buried in consecrated ground.

Giambattista Vico: Indeed humanitas in Latin comes first and properly from humando, “burying.”

Knausgaard sees his father’s body twice. Upon seeing it the first time he is overcome with nausea and grief that does not abate until he sees it the second time and realizes its meaninglessness:

I saw his lifeless state. And that there was no longer any difference between what once had been my father and the table he was lying on, or the floor on which the table stood, or the wall socket beneath the window…. For humans are merely one form among many.

In the context of a history that has repeatedly—ceaselessly—equated black bodies with animals and objects, however, we cannot understand the body as no different from a table or a tool.

The deceased is still more than just stuff, Heidegger writes, and yet, when we leave a dead man under an overpass for days covered in only a garbage bag, aren’t we treating him as though he weren’t? The slowness with which the dead were recovered in New Orleans following the flooding was not simple impropriety but revealed a profound disrespect for the humanity of the victims of the storm and levee breaks. And bringing the corpse back into our funeral rites is not a desecration or an impropriety, either; instead, perhaps unconsciously, this custom reasserts the body’s importance and restores dignity to the deceased, insists on the humanity of the dead. Uncle Lionel standing in his suit with his watch around his hand and Mickey Easterling in the floral pantsuit she’d specified in her will reassure us that proper care has been taken. In short, a funeral that ignores the body is not a luxury we can afford.

Unfinished Business

“Fifty-three, she’s not a normal fifty-three,” Mae Mae’s daughter said, wiping tears from her eyes. She’d given her mother a bottle of the scotch she liked, decorated her table with tiny Saints helmets. Mae Mae’s fingers were painted black and gold, and she wore a brilliant gold scarf, her hair neatly coiffed. On the table a ballpoint pen was ready on top of a book of find-a-word puzzles, and the glass of beer in her hand appeared half-drunk. She was a people person, her family said, always hanging out on her front porch to greet the neighbors or haunting her neighborhood bar, and she enjoyed a party. As her daughter said, “She likes to get down.”

In New Orleans, we speak of the dead in the present tense until a mass has been said, at which time the soul is “cut loose” from the body, a ritual based on the understanding that it takes us a while to separate the “who” of the person from the “what” of the corpse. In a jazz funeral, this happens when the coffin is brought out from the church and placed in a horse-drawn carriage. The procession to the grave begins in solemnity, with the band playing a dirge—most often the hymns “Just a Closer Walk With Thee” or “Just a Little While to Stay Here”—but as the funeral nears the cemetery, something in the tenor of the music and the dancing of the second line shifts. Baron Samdi, a spirit who wears sunglasses that help him see the worlds of both the living and the dead, turns away from the coffin and back toward the community. Once the crowd feels that its work of honoring the dead is done, its energies refocus on the living. People start hugging, grinding up on each other, getting down. The second line becomes sweaty, raucous, and life and fertility rush in to overcome the power of death.

Our lives are completed at the moment of death: until then we are incessantly becoming, our potential outstanding like a debt. But as soon as we are all that we are ever going to be, we vanish, and it is left up to the living to process the meaning of a life—or, rather, to give it meaning by transmuting being into something that was. As Robert Harrison writes in his wonderful book The Dominion of the Dead, Death “is an event that takes place in the aftermath of perishing, in and through the participatory care of the caretakers.” It’s our job to finish the dead’s unfinished business, take the whole of a life and house it in our memory, turn present into past. What the body can no longer do, we do for it: we bathe it, dress it, keep it safe. Much of this business has been outsourced now to undertakers, morticians, but back when the dead stayed in their upper rooms, had their hair washed by their daughters, lay unmoving in the candlelight as those keeping vigil spoke about them, and then of other things, before returning to their knitting, I imagine that transformation of present into past happened before the coffin was carried through the front door.

A proper process of mourning is for the living as much—or more—as it is for the dead. Unmourned bodies, unburied corpses, missing persons—they stay with us. They float like ghosts over corpses left in the sun.

Burying these dead would have required a special effort, a special mourning, but we were not even allowed to go back to the city to find them.

In New Orleans, there were 1,400 bodies. In the water, in the rubble. On the overpasses, the sidewalks. A 46-year-old woman named Vera Smith was buried by her neighbors under dirt and bricks and covered with a white plastic tarp that read “Here lies Vera. God help us.” A friend’s father remained in his flooded house for weeks, until she and her husband were allowed to return to the city to find him. They drowned, fell off bridges, died of heat and thirst and diabetic shock, committed suicide, overdosed on drugs, were killed by bludgeons and bullets. The water disinterred some from their graves. Refrigerated semis parked at the edge of the flood served as temporary morgues and, seventy miles away in St. Gabriel, the Federal Government’s Disaster Mortuary Operational Response Team spent six months identifying the bodies. The names of thirty-one remain unknown.

Burying these dead would have required a special effort, a special mourning, but we were not even allowed to go back to the city to find them. The cell phones were dead, and the bridges were guarded by men with guns. “Ignore the dead…. We want the living,” went the order to those men—proper on the surface, except that it ignored the more subtle truth that, unseen, unnamed, un-eulogized, the dead could not truly die. We, the living, imagined their escape. We searched the Internet for their names. We heard their voices. We set their place at the table, opened a window, watched the door.

Homegoing

My face appears, a shadow on the polished black granite, obscured by other shadows and reflections—the dark cloud-forms of trees, the white tombs glowing beyond the weed-grown lawn. Staring at a grave standing on a grave. Three years after the storm, the eighty-four unidentified or unclaimed dead were buried in six black tombs on the site of Charity Hospital’s potter’s field, where those killed in waves of yellow fever were interred in common graves. When the bulldozers came to make the mausoleums and lay the spiraling storm path, they unearthed fragments of bone. For legal reasons, the plaque at the entrance records only the donors’ names.

In Greek, sema means both grave and sign. A rectangular mound of earth with a stone on top means, and like all signs it points in many directions at once: to the human body buried beneath it, to who that human was (“Beloved wife and mother,” “Didn’t he ramble”), to the fact that we die, to the fact that we know we do. What it says eternally and most plainly is this: we were here.

“The surest way to take possession of a place,” writes Robert Harrison, “is to bury one’s dead in it.” The grave may even have been the very first “place”: while the living wandered, the dead had permanent homes in raw earth and terracotta, where, painted in red ochre, they slept with their arms wrapped around a jar of wine or the jawbone of a boar. Later, when the living settled, they built houses where they’d buried their dead—sometimes literally making those graves their foundations and basements—and they pointed not to those houses or the fields they tended but to the grave-posts, proof that their ancestors had been here before them and that they would be buried there in their turn, as signs of their legitimate ownership of the land.

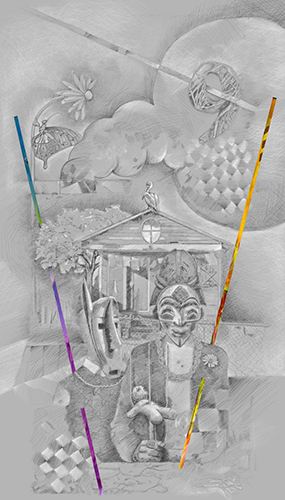

Photo caption: A refugee and her dog stand on an overpass overlooking a floating corpse.

Even before we left the city limits, we were refugees. The refuge of an overpass in the sun, of a blacked-out stadium where the toilets overflowed. The refuge of buses that came several days too late, of packed cars stuck in traffic while the storm gained on us. The refuge of friends’ jacuzzis and tumblers full of gin, of stadiums where the lights never went out and the babies never stopped crying. Refugees in our own country, as the country turned out not to be our own. “Refugees,” Gralen Banks told Spike Lee, “I thought that was folks that didn’t have a country.”

Driving through the anonymous traffic circles of the suburbs of our exile, my father kept saying: “There is no there there,” meaning here—Franklin—by there, and there—New Orleans—by the unsaid here. Meaning, away from home, we had no past and no meaning. Meaning our dead were elsewhere—in that city we weren’t allowed to enter—and this was not a place we were prepared to die. “What is a place,” Harrison writes, “if not its memory of itself.”

We returned to a city of empty streets, empty houses, empty houses slumped in the middle of empty streets. Most of us didn’t return. “A ghost town,” people kept calling it: so many souls un-homed. Between 400,000 and 600,000 of us were displaced. And if that trauma were not enough, for the majority left homeless, it was a trauma that recapitulated trauma: the original displacement of the Middle Passage, the violent removal from their African home.

“We celebrate the homegoing of people,” Lyelle Bellard told the cameras nine years later, explaining why on earth Mae Mae’s family would dance around her corpse. Homegoing means a procession of singing bodies dressed in white, conducting their dead to the grave in the middle of the night. Homegoing means manumission by way of death, a return trip to the coast of Guinea in a blink. “Guide me gently, safely o’er,” they sing, “to Thy kingdom’s shore, to Thy shore.” Homegoing means that, whether you came from New Orleans or Africa, heaven or dust, at death you return to the place from which you were taken.

When the water started to rise in Treme, Uncle Lionel, who grew up dancing in the Quarter and for many years helped to lead the Treme Brass Band, was at home, having a drink. If he was going to survive, he realized, he’d have to find a way out, and so, he told NPR, “I used my bass drum and turned it flat. Just paddled my feet.” He laughed, “And, of course, I had my liquor on top there.” When he died seven years later, the smell of barbeque wafted into the funeral home from the street, while trumpets and trombones blared over the heads of a crowd so thick it was hard to dance. Old ladies picked up their skirts and shuffled their feet, people applauded as his seven-year-old grandson performed a complicated step. In the front of the room, dressed in a pale suit, tasseled loafers, and a bowler hat, Unc leaned against a lamp post, his hands crossed over his cane—he never wanted anyone to look down on him, his family said, a request they took literally. His bass drum by his side, he had come home.

Why all this fuss? Why the jubilation? the reporters ask without asking, simply by coming, uninvited, into our funeral homes with their cameras. To this, we answer: we have returned, we reestablish our claim. A sprinkling of ashes isn’t good enough. You will watch us bury our dead in this, our ground. We are sons of this earth, we say, like Vico’s giants pointing to grave-posts, we are born from these oaks.

Outsiders attending New Orleans funerals—and they often attend, filing into church among the mourners, snapping pictures of the procession to the grave—do not always understand the dancing. Certainly, it does not belong to the sanitized world of tissues and organs and the quiet spreading of ashes. New Orleans funerals operate within their own system of taste, have their own codes of conduct and customs that were developed, in many instances, in direct opposition to that world.

Second-line culture began to take shape before the Civil War, when enslaved men and women were allowed to congregate only on Congo Square or in order to bury their dead. Burials provided an opportunity to keep the African customs and religious practices alive that slave owners were otherwise doing everything in their power to kill. Today, the attendants at jazz funerals and the participants in second lines maintain, sometimes subconsciously, the syncretic Voodoo traditions of following Baron Samdi, pouring out a drink for the fallen, and dancing the banda. After emancipation, African-Americans formed benevolent societies—a sort of proto-insurance system descended from Yoruba and Dahomean burial societies—which allowed their members to share the burden of funeral expenses, among other things. They would hire bands to accompany the funeral cortege to the gravesite, and those who joined the procession, coming out of their houses and up from the neighborhood through which the body traveled, were called the second line. These Social Aid and Pleasure Clubs, as they came to be known, now organize second lines that parade even in the absence of a body. Sometimes they march in honor of members of the club who have died, but often they march simply in order to dance, to see each other, to fill the streets with their presence. “They danced,” writes Joseph Roach in Cities of the Dead, “to possess themselves again in the spirit of their ancestors, to possess again their memories, to possess again their communities. They danced to resist their reduction to the status of commodities. In other words, they danced—and they still dance—to possess again a heritage that some people would rather see buried alive.”

The Social Aid and Pleasure Clubs create and maintain their communities, building cultural capital that cannot be accessed or drained by the people whose ancestors looked into the drum circles at Congo Square hundreds of years ago and said what they did was so much savagery—the antithesis of European taste, that Other against which they defined themselves. The clubs address that judgment deliberately, subvert and parody it. On Mardi Gras morning, while the Rex Parade travels through the city, the anointed, pink-cheeked King of Carnival waving his scepter from a throne beneath a huge papier-mâché crown, the Krewe of Zulu—itself a Social Aid and Pleasure Club—rolls out of Central City. Its black members, in blackface, throw coconuts, and the Zulu King on his float is mast-headed by a leopard. In 1909 Zulu’s inaugural members had seen a comedy skit about the Zulu, “There Never Was and Never Will Be a King Like Me,” at the Pythian Theater. Since then, there always has been.

The music, forged by people taken from Africa, enslaved and free, in Congo Square and in Storyville, floats across the city as the coffin of the dead man is carried on a route that passes his house, his work, his favorite bench.

New Orleans’s funeral culture insists upon the value of life even against its inevitable end. As Helen Regis argues compellingly in her article “Blackness and the Politics of Memory in the New Orleans Second Line,” the New Orleans jazz funeral asserts ownership against dispossession, presence against erasure, memory against forgetting. Of Big Chief Donald Harrison Sr.’s funeral, Kalamu ya Salaam writes, “I was here to bear witness with the vibrancy of my being, with my tongue chanting and body dancing, with my soul intertwined in celebratory resistance shout with all the others of us all in the street—no building, no structure, no coffin, nothing could contain us.” These funeral processions fill the streets, hold up traffic. Men jump up to hit the signs that say Stop and Yield. The music, forged by people taken from Africa, enslaved and free, in Congo Square and in Storyville, floats across the city as the coffin of the dead man is carried on a route that passes his house, his work, his favorite bench, his favorite bar, his favorite tree, engraving his memory on the neighborhood where he lived and in the minds of those who pour out their drinks for him onto the ground and dance him to the grave. Pallbearers have been known to throw a coffin into the air—not because they have forgotten what it contains, but because they remember. The dancers wearing memorial t-shirts aren’t disrespectfully informal—they bear the dead man’s image, enacting with their living bodies the raw absence of the departed. His face fills the streets, printed on fans and signs, in blown-up photographs placed in wreaths. “The entire parade is transformed into a memorial,” Regis writes, “signifying a refusal to forget, to allow a single life to dissolve in the oblivion of anonymous statistics, sterile numbers published in the aftermath of violence.”

Regis gives us this scene from the funeral of young man who was killed at seventeen by a bullet:

Moments later, the parade resumed, swelling in size to three- or four-thousand people as we headed down Orleans Street toward the housing projects. Dozens of men were emptying their bottles of beer over the hearse, to the dismay of the funeral director, who was powerless to stop it. Boys shook and sprayed their beer over the crowd, circling bottles above their heads…. The sun was bearing down hard on our handkerchiefed heads and on the asphalt of the Sixth Ward streets. I stopped briefly to buy some bottles of water and beer from vendors, and when I next looked up to the head of the parade, I saw [the boy’s] mother, dancing above the crowd, floating impossibly over the mass of second liners. I made my way through the crowd, straining to see what was happening. “What is she standing on?” I asked a fellow second liner. “She dancin’ on his coffin,” came the answer in a mixture of awe and dismay…. “I have never seen a mother dancing on her son’s coffin!” [She] was unambiguous in her disapproval, but [the boy’s] mother continued to dance to the driving sounds of the ReBirth Brass Band…. Clearly for [some], the funeral’s embodiment of respectability should not be traded for a mother’s ability to express her emotions in such trying circumstances.

A grief that leads a mother to dance on her son’s coffin is a wild, bleeding grief—it is hard to face it, hard to accept it, and so we might call her dancing distasteful, we might choose to look away. That judgment, though, has nothing to do with the mother’s loss, and everything to do with our fear that we might have to experience that loss as our own. It is a judgment based on our desire to avoid feeling that grief ourselves—but perhaps it is better to feel it. Perhaps the defiant dance of a mother over her son’s dead body is a screaming, healing truth.

The Katrina memorial is in the guidebooks: “It’s an unfussy place that’s easily missed, the better for contemplative solitude, perhaps.” True to billing, there was no one there the day I went, but there is a second line nearly every nice Sunday, and the crowds are thick.

America is ready for a granite memorial perhaps, but New Orleans isn’t, not yet. To paraphrase Pierre Nora: we need no monuments, no lieux de mémoire, while our culture still remembers. A remembering culture does not live in the past but “ceaselessly reinvents tradition, linking the history of its ancestors to the undifferentiated time of heroes, origins, and myth… With the appearance of the trace, of mediation, of distance, we are not in the realm of true memory but of history.” In New Orleans, we don’t need to hide our ashes in pretty urns. We look straight at our bodies. We are in the realm of memory every day, sleeping in the beds our grandmothers were birthed in, maintaining houses our families have owned for generations, making red beans every Monday. We walk on sunny days through our mausoleum cities, singing old songs, and we talk about what we ate for lunch while eating dinner. Our halls are crowded with armoires, our attics crammed with dubious treasure, and our doorposts—some of them—are still marked by Katrina’s graffiti: an X spray-painted by the patrols in the weeks of abandonment, annotated with dates, codes, occasional words (1 Dead in Attic). They look like nothing more than the markings of blood on the doorposts of Egypt, telling the angel of death to go on his way. We do not want our wounds to heal quickly. We have no desire to move on, to forget. Forgetting fixes nothing—it only adds to the sum of what we have lost.

Just a Little While to Stay Here

Kalamu ya Salaam: This is why we don’t die, we multiply. Every time the butcher cuts one of us down, the rest of us laugh and dance, defying death. It’s our way of saying yes to life, saying fuck you to death and his nefarious henchmen, poverty, and racism.

If we dance around our dead, it is because we have to. The knowledge of our mortality keeps us going in its face. A thousand times flooded, twice burned, and beset from its founding by disease, poverty, racism, and guns, New Orleans has always been on the brink of nonexistence. Our position on this crescent of deltaic mud at the juncture of a great river, a lake visible from space, and a deteriorating swamp—or rather our awareness of what that positioning means—is what keeps us alive. Since Bienville convinced France not to abandon the flooded and underpopulated town, we have never been able to ignore the destruction that awaits us, and we’ve used this knowledge to build a sometimes bawdy, always loud, expansive, welcoming, deeply human culture, a culture that celebrates drinking in the street, sweating through your clothes, dancing all night, and putting a ham hock in pretty much everything. We let the good times roll, because they might not roll long. If, following our most recent encounter with the forces of destruction, we have brought an unmoving corpse into the middle of our dancing, it is not out of morbidity or numbness, but because the onrushing fact of our disappearance only brings our living into focus. “Is it only by looking deliberately into the abyss…we stand in the middle of that we come alive to the world?” Harrison asks. The song answers:

Soon this life will all be over

And our pilgrimage will end

Soon we’ll take our heavenly journey

Yeah, and be at home with friends again

Heaven’s gates are standing open

Waiting for our entrance there

Some sweet day we’re going over

And all the beauties there to share

That’s why I’m saying

Just a little while to stay here

Just a little while to wait

Just a little while to labor

In the path that’s always straight

Listen to it, here played by the Eureka Brass Band: I dare you to labor—or even walk—in a straight path. This is music to dance to, lyrics to sing if you need something to make you feel fully alive, fully yourself. Being human is being toward death—the vanishing moment at which our possibilities are exhausted and we are complete. Authentic being is living in the knowledge that we could arrive at our completeness at any time. At any moment, the black cloud could appear spinning in the sky over our heads. At any moment, we are all that we might get to be.

The dead sit, unmoving, hands wrapped around their drinks—voided but not voided, reclaiming ground, reclaiming life here, even as they have lost it.

“Death,” Heidegger writes, “is a way to be,” by which he does not mean that we should all wander around gloomily contemplating our end. Instead, the inevitability of death should foreground life, bringing our attention to its value. In dedicating music and dance to the dead, in putting on our memorial shirts, in remembering our ancestors as we make their recipes and sing their songs, we consecrate our lives. What we give to the dead—a batch of gumbo z’herbes, a forty poured in the gutter, a passing thought—breaks loose from the quotidian and begins to shine. Recalling the dead also recalls us to our world, the world of the living, our lives, ourselves.

Scholars like to say that the grave was the first sign, but the body, itself, came before. Sitting on their kitchen chairs, in their garden benches, leaning on their canes, they serve as monuments to life, to loss, memorializing everyone the city lost, everyone who returned and who could not return and all those who vanished or remain unnamed. They sit, unmoving, hands wrapped around their drinks—voided but not voided, reclaiming ground, reclaiming life here, even as they have lost it. I can think of nothing more honorable, more tasteful, more proper. If truth is beauty, nothing is more beautiful than this.

On Mardi Gras morning, the Skull and Bone gang goes from door to door in Treme, waking the neighborhood. They lurk around the outskirts of the parades all day, boys and men in skeleton suits tapping people on the shoulder with rubber bones, whispering, shouting, “You next.” Destruction looms over every New Orleans day, and so we are more open—even those of us without religion—to the city’s reminders, shouted at us by our priests of Catholicism and Voodoo and ruin, of the thinness of the membrane between life and death, the speed with which a bullet can find us or a cloud can form. So, give this body a glass of champagne, a pack of cigarettes, turn on the music. Everybody, get yourself up and dance.