I once woke up in the back seat of a car with blood sticky on my chin and an ear that throbbed as it purpled. Another time, I fell down a flight of stairs and sprained each of my elbows and wrists. There was a twisted ankle, a bike wreck, a concussion, an assault — hammered, I hardly felt any of it.

It wasn’t until I got sober and started taking care of my body that I began to feel pain. This meant pain pills were off the table when I needed them most, on days like the one when I had my abortion.

I was reluctant to accept the good stuff at my local clinic in Portland, Oregon, though plenty of it was on offer. OxyContin, Klonopin, Vicodin, Valium. I used to mix these pills with golden mouthfuls of malt liquor and cheap whiskey slugged straight from heavy glass bottles, and I had learned not to trust myself under their influence.

Before the procedure, I sat on the exam table, trying not to disturb its protective sheet of crackly white paper while I disclosed my history of substance abuse to the nurse, who called in the doctor to consult. I opted for an eight-hundred-milligram shot of ibuprofen, which the nurse administered via syringe into the thick meat of my butt cheek, and which the attending physician insisted would be sufficient to manage my pain, along with a local anesthetic injected into my cervix.

“I do abortions all the time in rural and free clinics, and this is all they ever have,” the doctor said. “You’ll be fine.” Percocet, Demerol, Adderall, Ambien. Some people get drugs, and some don’t.

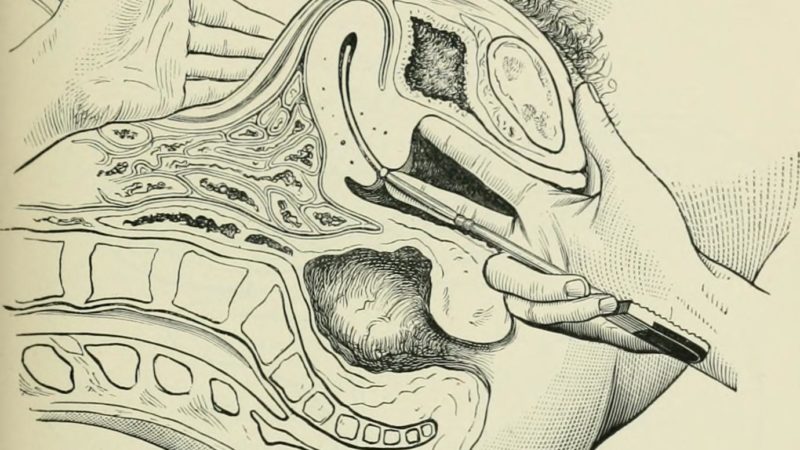

I was having a D&C — short for dilation and curettage — an abortion in which the practitioner dilates the cervix, either with medication or by inserting a series of rods that increase in size, like Russian nesting dolls, then uses a curette to scrape or suction out the contents of the uterus. Generally, patients are sedated or even unconscious during the process, as well as locally anesthetized, to guard against the significant physical discomfort of having an internal organ stretched, dredged, and vacuumed out.

After the pinch of the local anesthetic, I felt nothing for about thirty seconds, but then the scraping began, along with the suction necessary to remove the resultant loose lining. I fought the urge to rip the instruments from my vagina. My howls reached the lobby. To keep from moving, I gripped the sides of the table, my knuckles white as molars. How familiar, I might’ve thought, had I been able to think. White knuckling is a phrase used in recovery circles to describe the state of willfully resisting the urge to use by holding on for dear life to something — anything — besides a pipe, a pill, or a bottle. Xanax, Neurontin, Ritalin, Robitussin. What can we do when pain and survival become synonymous?

An estimated nine hundred thousand abortions are performed in the United States each year, and despite the rising popularity of abortion pills, around half are surgical, like my D&C. As with substance abuse disorders, social and legal sanctions for abortions compel secrecy among those who seek treatment.

There were other parallels between my alcoholism and my abortion. The physical agony of termination echoed the spiritual midnight of hitting bottom, back when I would do almost anything to stay intoxicated. Nitrous oxide, psilocybin, nicotine, pseudoephedrine. Then there was the voiding of my insides, the blackout, the loss of control over my body, the paradox of choosing one pain to avoid another, the taboo, the shaming, the blood, the ways pregnant people and addicts are distrusted.

I hail from a long line of alcoholics and junkies. Substance use disorders run in families, as does poverty, and the traumas caused by both turned me away from having children. Growing up in rural Oregon — in one of the small towns to which my own doctor likely traveled to perform terminations for poor, uninsured people — I watched the adults in my family do jobs they hated, jobs that hurt and bored and underpaid them, jobs in which they felt trapped; they had kids to feed. Many used substances to self-medicate and to survive, even when it meant institutionalization. Methamphetamine, tetrahydrocannabinol, ethanol, cocaine hydrochloride. Their agony was multivalent, and their choices were few.

I didn’t choose to become an alcoholic, nor did they. But I did have the choice to remain childless — a choice born of their pain and that of countless others. The pain of curettage was acute, but like my time spent in active addiction, it was blessedly short. Recovery meant turning away from one version of my life and toward another, this one brighter, harsher, more fully awake. It made terminating my pregnancy both a choice and a refusal.