I stopped dancing the summer I turned fifteen. It was the summer Michael Brown was shot by police in Ferguson, MO; the summer I began to really think about my skin; and the summer I started to understand just how vast the chasm really is between the lives of white and non-white Americans.

That summer weighed heavy on me—as it did on countless others—but my decision not to return to the Ailey School predated the grief, the protests, even the murder. It had more to do with my teenage petulance, with frustration over my regimented schedule: the hours spent driving to and from class, the weekends lost to rehearsals and physical therapy. I wanted the chance to engage with other things, sure; but mostly, I wanted the freedom to engage in nothing if I so pleased. I couldn’t see at the time that the end of my relationship with Ailey, the last of my tangled efforts to avoid confronting race, would force me to do the opposite.

The first time I saw Revelations, Alvin Ailey’s signature choreographic work, it was not from the audience, but from the wings. I was nine years old, anxious, sweating through my white leotard, fidgeting with the long skirt that cascaded from my waist. I had been a student at the Ailey School for a few years, but that night was the first time I had been selected to perform with the adult dance company.

They had simplified the choreography for the other child dancer and myself, so the steps weren’t particularly challenging or complex. Still, I tended to overthink before going onstage, repeating the steps in my head until they blurred and lost their meaning. I was determined not to do it this time. The piece felt too heavy, too important to dissociate from for anxiety’s sake.

Revelations was Ailey’s masterpiece: a work about God that transcended religion, a piece about blackness that had somehow hurdled its way onto white America’s stage. The adult performers imparted a sense of urgency, an acknowledgment of the dance’s depth and darkness, and I felt duty-bound to do the same. I crouched in the wings, carefully fanning out my skirt so as not to dirty the white fabric, and waited.

The movement of black bodies in America has always been linked to the restrictions, indignities, and brutality inflicted on those bodies. In 1961, forty-six years before my first performance—the same summer that Freedom Riders made their first trip South—Alvin Ailey headed north, putting on the first production of Revelations at the Jacob’s Pillow dance festival in Lenox, Massachusetts. The piece stunned audiences, not only because of its artistic and choreographic value, but because it allowed the black performer subjectivity, and the black body agency, before a white audience. After 400 years, that body could initiate as well as respond.

As the renowned dancer Katherine Dunham put it, Revelations “presented dark-skinned people in a manner delightful and acceptable to people who had never considered them often even persons.” More than that, it presented largely white audiences with a story in which their ancestors and relatives were the antagonists—invisible, but nonetheless pervasive in their oppression.

The choice to use spirituals as the musical force for the piece was born of Ailey’s own Baptist upbringing in Texas, and that choice enabled him to further politicize his work. Henry Louis Gates Jr. has said that spirituals hold “such import to black poetic language that when they surface as referents in poetry—spoken, sung, or danced speech—they cannot but bear the full emotional and structural import of another lurking, but not lost, hermetic universe.”

Ailey’s poetic universe was anchored by the strong, grounded movement of choreographer Lester Horton. One of the first choreographers in the US to insist on racial integration in his company, Horton developed a modern technique based on Native American dances and anatomical studies. When he passed away, Ailey—a former dancer in Horton’s company—briefly took it over before starting the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theatre. The pairing of the two choreographers formed the strong yet supple backbone of Revelations, through which dancers brought to life an entire history of sorrow, spirituality and joy.

At least some dancers did. But I had never felt fluent in black poetic language—not proficient, or even conversational. How was I to access the pain and triumph of a history that was not mine?

***

Horton had always given me trouble. The Ailey School required students to study ballet and modern dance technique each year, with other dance styles added depending on age and skill level: African, tap, jazz, character. Ballet was always my best class. I liked it because I understood it and was good at it, but also because it felt sanitized, detached from any tumultuous history. Though delicate and difficult to reach, ballet was entirely accessible to me. It always struck me as odd that our ballet classes were followed by Horton classes three days a week. The two seemed diametrically opposed. In the time it took to unlace your pointe shoes and roll your tights up to your ankles, you had to undergo an entire metamorphosis—you were no longer weightless, no longer lithe. If ballet required you to be like the fronds of a willow tree, Horton required you to be the roots.

It wasn’t the technique that tripped me up. As I progressed at Ailey, I was strong and flexible from years of training, and could execute the lateral Ts and leg extensions with relative ease. Warm-ups, which consisted of strength exercises and stretches to simple piano music, were fine. I could focus on the technique, on the lines of my body and the strength of my core. I figured that dance, when simplified, was nothing more than making shapes.

But when it came to choreography, put to gospel music and prayer, it felt disingenuous, like I was expressing feelings I’d never felt, dancing a story that wasn’t mine to tell. The things that made me a good ballerina—composure and discipline—were the very things that had my Horton teacher gesturing frantically as I made my way through a piece, drawing wide circles around her face with her index finger: “Emote, Jamila! Emote!” Revelations’ religiosity came, in part, from Ailey’s confidence that his all-black dance troupe could connect to the material and its cultural importance. As the African American studies scholar Thomas DeFrantz put it, the dancers were “fully aware that the dance represented a history of a people’s faith,” and so they “filled out the movement patterns with a sense of drama, with passion and zeal, with what Ailey later recalled as ‘menace and funk.’”

The dance drew on centuries of physical bondage, exclusion, and social and financial redlining. The piece was as black as Ailey was, made by and for people whose choreographed baptisms and prayers and histories were reflected on the stage.

I had grown up 1,665 miles from Ailey’s Texas, in a Hudson River village. Catholic school had squeezed any trace of spirituality from my father long before I was born, and my mother believed in God in the same way others believe in astrology or karma: she is spiritual on good days, and hopeful on bad days, and ambivalent on the days in between. To say I had not been raised religious is understatement.

But my discomfort with Revelations went beyond the fact that I had never read scripture, never been to church. Race was something that made me uneasy. I was brown, had a name that disintegrated in the mouths of white teachers, had a grandmother who wore a sari on special occasions. But my father was white, and I lost much of my melanin come winter. The stories I was performing were not my own.

The racial reality of this country is that blackness is inherited, passed down through blood—and histories of violence, discrimination, and disenfranchisement are passed along with it. You cannot access blackness if it hasn’t been imposed upon you in the first place.

If my Indian mother marrying my white father had been the extent of my racial history, my feelings toward the piece might have been less convoluted. But my relationship to Revelations was complicated by a re-marriage in 1966, decades before my birth, when my Indian grandmother married an African American man from Bed-Stuy. He was father to my mother and the only grandfather I had ever known—family in all but blood.

My grandfather had his own fraught relationship with his heritage. A classical violinist, he had made his living expressing the white, European canon for white audiences. Just as my dance training had taken me from the suburbs to the Ailey School, his training tugged him through a reverse commute, from his public school in East New York to a school for “gifted”—read: white—students in Manhattan, and classes at Julliard. He was the first—and for years, only—black musician in the New York Philharmonic. He betrayed no intonation or other clues of where he had grown up, painstakingly articulating each word with a clarity that always made me think he’d make a good NPR host. But while my grandfather was intentionally selective about what aspects of blackness he chose to embrace, it was his to embrace as he deemed fit. Dancing Revelations, I felt like I was just borrowing it.

At nine, racism was something I largely imposed on myself, wishing I could have blonde hair or blue eyes or hairless arms. I was often asked questions by strangers in Spanish, and more than once in Arabic, after which I would fumble and try to apologize. I was accustomed to racial ambiguity but not comfortable with it, still trying to reconcile perceptions of me with my actual self. I was unsure of my racial and cultural identity, of which aspects I could lay claim to and which I could not. This is a discomfort familiar to mixed-race people, and perhaps also to the colonized, those with eclipsed and interrupted histories tugging rearward.

But that’s also the nature of being brown, not black, in America. While the line between the two may blur, the distinction is important. I had been shielded from the depths of American racism, its ugliness and resilience. As a child, I didn’t question why many of my black classmates lived in the same stretch of squat brown housing projects. I’d never experienced the brunt of police brutality, nor the loss of a community to over-policing and mass incarceration. I didn’t understand the full breadth of the trauma and pain behind Revelations, how anger nourished its roots—the lynchings in Depression-era Texas, segregation, poverty, the rape of Ailey’s mother by a white man. I knew as much about slavery and its legacy as most schoolchildren, which is to say I knew nothing at all.

***

The section of Revelations I was performing that night was perhaps the most famous. I would perform it another eight times in subsequent years, in venues ranging from the Apollo Theater to the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade. “Wade in the Water” is the center of the dance, following the devastating “Pilgrim of Sorrow” section, in which soloists and pas de deux play out, expressing anguish, hopes for redemption, salvation, relief, freedom.

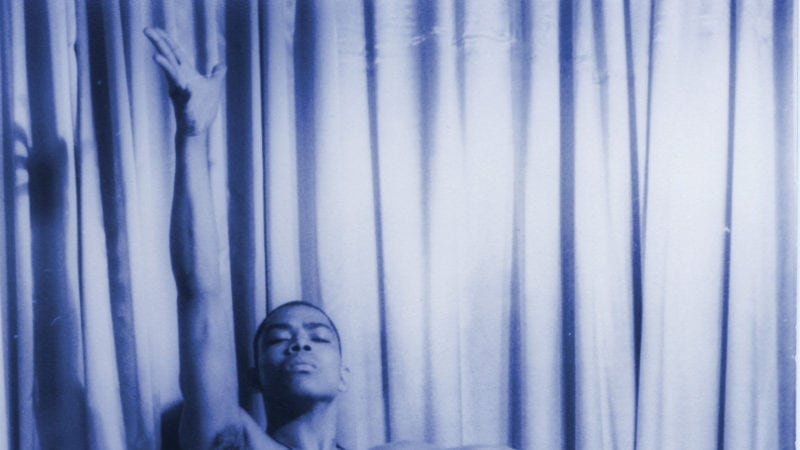

That first third of Revelations is harrowing, difficult to watch but impossible to pull your eyes from. It always left me feeling winded, standing in the wings. From there, the piece rests for an instant, only to catch new air beneath its wings, and then soar. It shifts from mournful solemnity to the joy of a waterside baptism, of new life. Dancers burst onto the stage, their bodies erect and strong, their jubilation tangible. There is a certainty to their steps: a sense that, in spite of the spontaneity, the choreography is embedded in the dancer’s biology, and always has been. It is forceful without pushing, reaching the fulcrum of a feeling, of a movement, without ever flailing over its edge.

Back then, I couldn’t understand how the performance was able to make such a transition with so much grace. On stage that night, I dutifully performed the movements. I spun, and kneeled, and bowed. I could hear my teacher in the back of my head yelling, “Emote, Jamila! Emote!”

But I didn’t.

I couldn’t forge a connection to the piece, and the prospect of really grasping its magnitude, and that of the spirituals behind it, felt too daunting a task. It was easier to dissociate myself from it, to memorize and perfect the choreography without stopping to consider what it meant to me, and how I fit into it all.

Repetition didn’t help. It seemed the more I was asked to join the adult company, the more performances of the piece I did, the easier it was to distance myself from it. Revelations began to feel rote; I might as well have tried to channel the emotions of the sugar-plum fairy.

My departure from the Ailey School was mostly unceremonious. I had always dreaded going to class, always loved it once I was there; but by age thirteen, the dread had begun to follow me into the studio. During Saturday morning warm-ups, I found myself dwelling on thoughts of my friends leading more exciting lives—staying out late on Friday nights, seeing movies with boys at the mall after school. In hindsight, Ailey and the opportunities it afforded were, arguably, the most exciting things to ever happen to me. But no one praises adolescents for their ability to prioritize. I could think of a thousand good reasons to quit: I wanted to join the lacrosse team, I wanted to sleep in on weekends, I wanted to spend a full day at school after years of leaving early to commute. In the end, there was only one reason that mattered: I didn’t know what I was doing there.

The summer I left, I had time on my hands. I started reading the news, started to take note of which bodies were photographed bleeding out in the street. I watched grand jury after grand jury fail to indict, and began to realize what it was I had been trying to dodge.

The news magnified my anxiety, and gave context and force to a previously vague apprehension: if you’re not white, you’re powerless before those who define you. Powerless against assumptions about your racial identity. Powerless against white people who, regardless of your accomplishments—dancer, choreographer, violinist—will treat you as other, and perhaps as inferior. Powerless against the structures that decide your body can be left on the street while the policeman who murdered you goes home to his wife. Powerless against the choreography of oppressors.

Distance from Revelations didn’t simplify my relationship to it. An awareness of violence against black bodies didn’t translate to an understanding of it. Dance’s beauty resides in the empathy established between performer and audience. That much I knew. But I found myself coming back to the same question: what does it mean for non-black people to spectate, to participate in movement inspired by black pain?

For Ailey, and for the African American dancers performing Revelations, the dance might serve as catharsis, an opportunity for transcendence beyond the forces that bind blackness. Their stake in the piece predated them: they could not choose their history, their body, their race, in order to avoid discomfort. They carried the weight of the story, whether they chose to perform it or not. Better to own it.

As a child, the piece taught me plenty: that black people had endured a crucible that I had not, and that despite this—or, rather, out of this—they had made something of extraordinary beauty and durability, something I had the privilege of participating in even though it wasn’t mine. It taught an agnostic, mixed-race child about the beauty of Southern Baptist tradition. It taught ambivalent white audiences about the costs of slavery, and the divine fortitude of black people. At least, it tried.

Revelations has been joined, over the years, by new pieces, ones inspired by the speeches by Martin Luther King, Jr., ones registering the pain of mass incarceration. In 2018, the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater celebrated its sixtieth anniversary season, adding to its repertoire two new works. One is Lazarus, a celebration of Ailey’s life by hip-hop choreographer Rennie Harris, which draws on the Philadelphia style of street dancing known as GQ, set to a soundtrack that samples everything from the sound of weeping to Kendrick Lamar. The other, The Call by Ronald K. Brown, is set to Bach, jazz, and Malian music, and mixes modern and African dance.

Brown’s work, in its final moments, mirrors the motion by which Revelations has come to be defined—raised arms, chest and head facing skywards, uplift embodied. But Lazarus’s sound samples—gunshots, the growling of police dogs, the spray of fire hoses—seem to question why some of these lessons are never fully learned, even after all these years. They gather force and coherence, then come unraveled again. I’m still watching from the wings, anxious about what’s to come.