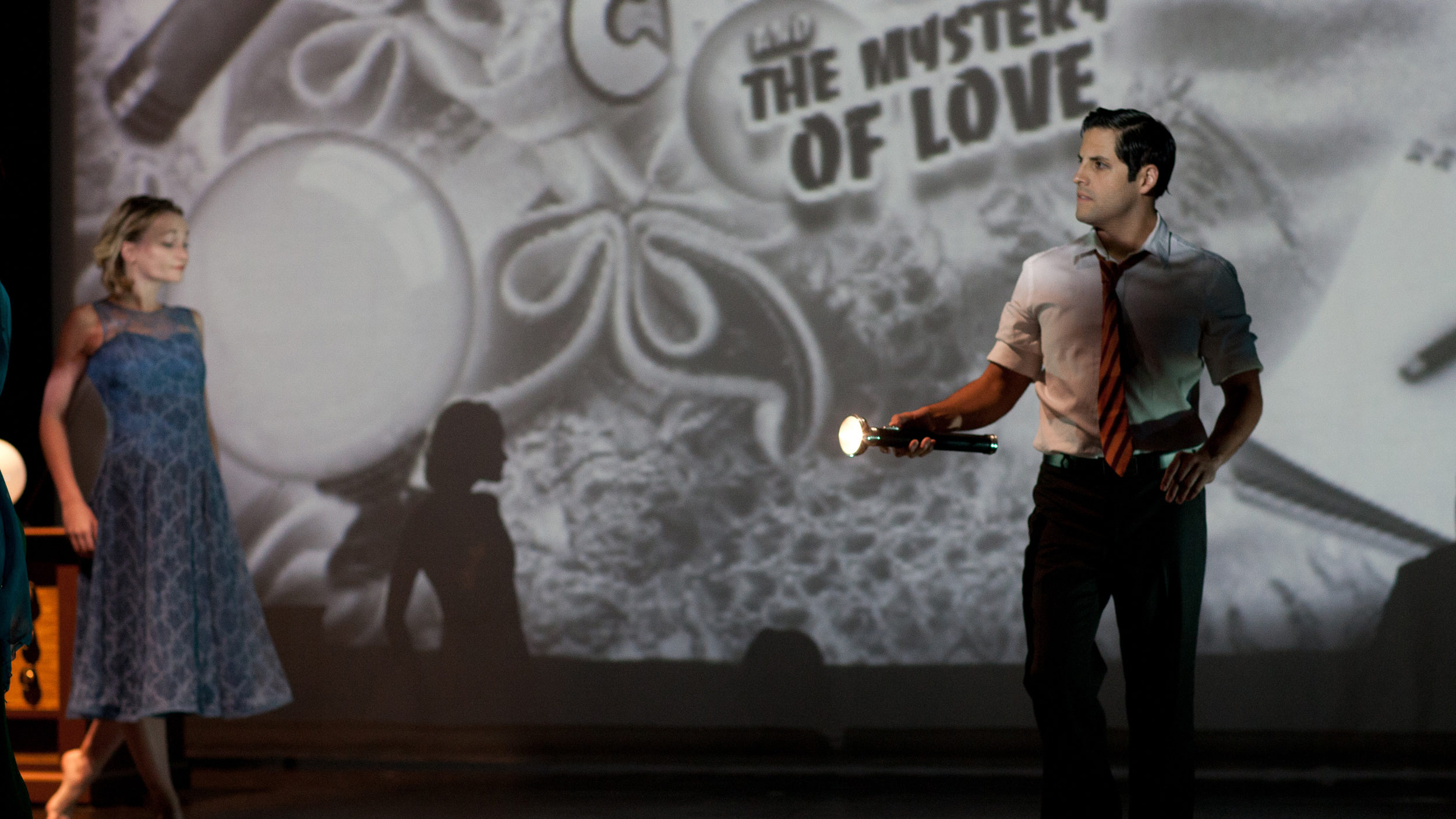

Watching a dance by Dana Tai Soon Burgess is like seeing a dream unfold on stage—bodies draped in luscious fabrics contort and flow to music and sounds that feel familiar, but are hard to describe in words. Heavily influenced by his cultural background, Burgess’s work feels both specific and universal. Sometimes he projects Chinese characters from letters written by immigrants arriving at Angel Island onto the floor below his dancers. Sometimes a traditional Korean mask appears, unexpectedly, on a dancer’s face. Other times, performers bow, rock back and forth in hesitation, or crumple as if crying.

Burgess is one of the few modern Asian-American choreographers widely recognized for his work by the mainstream dance community. Born in Carmel Valley, California, to a Korean-American mother and a European-American father, Burgess’s journey toward curating movement began when his father enrolled him in a karate class. Burgess went on to study dance and Asian history at the University of New Mexico and received his MFA at George Washington University. In 1991, he founded his dance company, Moving Forward: Contemporary Asian American Dance Company, which would later come to be known as the Dana Tai Soon Burgess Dance Company.

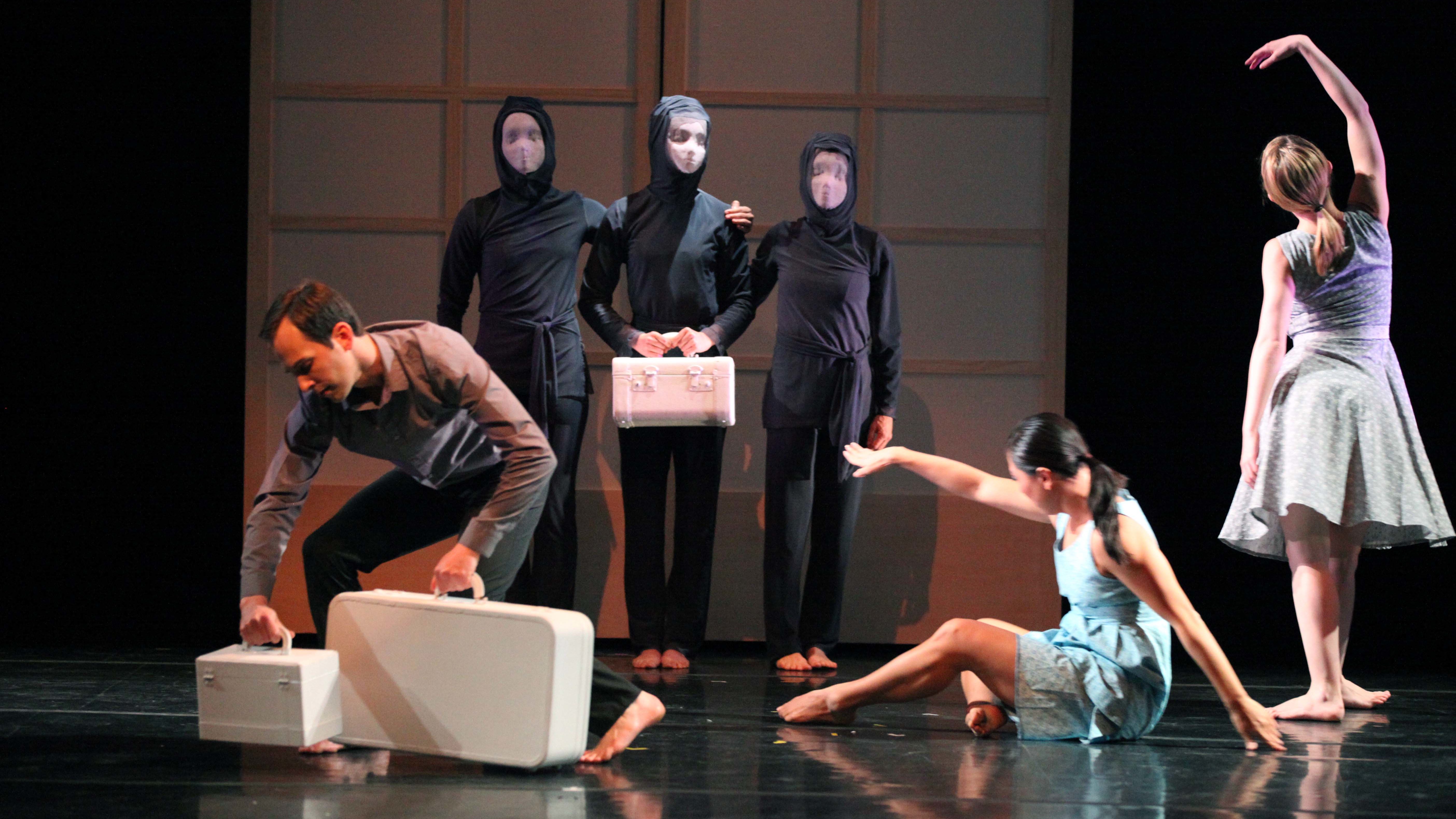

The performers in Burgess’s pieces are a reflection of his varied heritage: his dancers are Caucasian, Hispanic, Asian American, of mixed heritage. “It’s like I have the contents of my mind on the stage,” he said during a performance at the Flashpoint Theater in Washington, DC, this past summer.

I reached Burgess while he was on a trip to Santa Fe, where he grew up, and we discussed finding inspiration in invertebrates, making personal histories abstract onstage, and bringing audiences to dance about an Asian-American experience.

—Jenny J. Chen for Guernica

Guernica: Tell me about starting your dance company.

Dana Tai Soon Burgess: I started it in 1991, when I was twenty-three years old. I was dancing for a lot of different companies, and I just decided I wanted to start choreographing. I had this small group of dancers. I was showing my work in tiny places—anywhere people would see them. There was a cabaret, a movement series in a chapel, on the steps of the Lincoln memorial, just all kinds of things…

I had one solo that used these large willow branches and pond rocks, so anytime I got a booking for that solo, I would have to go to a nursery. Back then, I didn’t have a car, so I would have to take a bus to buy three bags of rocks and carry six or seven of these willow branches. Then I’d have to get back on a bus and figure out how to get to the theater. By showtime, I would have trekked all over DC with fifty pounds of rocks and giant sticks. It was hilarious and bad at the same time; it could have been easier if I hadn’t chosen to use those props.

I was choreographing while I was a dancer, but by 2007 I’d had a series of back injuries. I knew that, as I was getting older, it would make more sense to have younger dancers on stage while I honed my craft as a choreographer from the outside.

Guernica: Why did you choose to start your own company as opposed to just choreographing for other companies?

Dana Tai Soon Burgess: I wanted to tell stories through dance that were [nearer] to an experience I felt close to. I don’t think it was until I turned twenty-eight that it hit me—There is no turning back. There was no other career that I would be as happy in or that would sustain me creatively throughout my life, so I realized I needed to push the company to new heights in order to make sure that I always had a mechanism to create dances.

There really weren’t any alternatives. Maybe I could have gone back to school for an art degree but that wasn’t where my heart was. As a choreographer I knew that I could shape an aesthetic; I could create dances that made sense to me and that could represent my subconscious world. But building and running a dance company is tough because, although I started the company to choreograph and support dancers, there are so many other skill sets that have to be developed: understanding how to collaborate with designers, fundraising, programming a season, touring logistics. It really does take years to develop a process that delivers new work consistently.

Guernica: How is being a choreographer different from being a dancer? How have you grown as a choreographer since you began doing it full time?

Dana Tai Soon Burgess: [As a choreographer] I have distance from the body that is the medium and can manipulate the dancers more easily. I’m more experimental, I’m more interested in finding out the idiosyncrasies of each dancer. A young choreographer often gets hung up on thinking they have to have all the answers. As a choreographer ages, they realize that they’re more of a steward to movement. We mold movement and curate and form it into plausible and understandable stories.

I’ve always been inquisitive about movement in terms of watching it, exploring it. I’m obsessed with the way people walk down the street and with looking at the different tempos in different cultures. I like to watch out for the unusual movement patterns of our company dancers.

Guernica: What can you tell about a person from their movement patterns?

Dana Tai Soon Burgess: I can tell a lot of things: if pain is in the body, whether someone is depressed, what age they are. When you see someone whose chest is withdrawn, their deltoids are rolled forward. That’s someone whose history has broken them, in a sense. You can recognize that movement of pulling away and protecting the heart across all cultures.

Guernica: You said that you look for idiosyncrasies in the way your dancers move. What types of things are you looking for?

Dana Tai Soon Burgess: Everyone has a tendency to move in a certain way based on how we’re raised and how we’re predisposed. It’s helpful for me to look at different movement patterns that break my own movement as a choreographer. Some people sequence movement from the core of their bodies outwards, and some people move from the distal ends of their bodies inwards—those have very different looks. Some people are quick-twitch muscle fiber movers and some are more flow/adagio movers. When you’re creating a piece of choreography, you don’t want to be telling the story at the same rate all the time. You need all those gradations of movement in order to make a successful dance.

Guernica: Are there exercises you perform with your dancers to explore how they move differently?

Dana Tai Soon Burgess: Sometimes I’ll come up with a phrase and introduce it to my dancers. Then I’ll ask them to manipulate it with a partner—working with the negative and positive space, changing the timing of it, or maybe by making it so that they can’t do the phrase without being continuously attached to someone. I do a lot of game playing like that so the dancers can create something completely new.

Guernica: What was your first big break as a choreographer?

Dana Tai Soon Burgess: My Asian-American youth dance program was doing Hans Christian Andersen’s “The Nightingale” at Dance Space and the Lab Theater at the Kennedy Center. The VP of education at the Kennedy Center saw it and said, “If you could rework that, I think we’d like to hire you as a choreographer and start touring [the dance] around the country.” That was a huge turning point.

Then, [starting] in 1998, we were presented by this curator at the Kennedy Center for several years in a row, which allowed me to build as an artist and gave me a home studio, which is very unusual. That solidified space for me. After one performance, the State Department came to me and said, “We would like you to start touring abroad as a cultural envoy.” That was life-changing because it allowed me to do the international work that I do now.

Guernica: When you were first starting out, was it difficult to get people interested in watching dances about the Asian-American journey?

Dana Tai Soon Burgess: Oh yeah, definitely. It was very difficult, because they would think, “Oh, we don’t want to see another fan dance.” They couldn’t wrap their heads around what Asian-American dance might mean. I think it took audiences a couple years to understand that the APIA [Asian and Pacific Islander American] experience shares certain universal elements with all communities: issues of belonging, community, seeking a new life in a new environment, love and loss. Once people saw that we were doing contemporary work that told abstract stories grounded in historical events and personal stories, the company really took off.

Guernica: Who did you look to for inspiration in depicting the Asian-American experience through dance?

Dana Tai Soon Burgess: That is a tough question because there were so few people doing APIA work at that time. Michael Mao and HT Chen were established choreographers in NYC who were successfully creating works about the APIA experience. I appreciated their dedication to their art form and their belief in the community.

For specific pieces, Michio Ito, the first Asian-American choreographer (who was Graham’s and Horton’s teacher), really inspired me. I met some of the original Ito dancers and I said: “I know you’re not really actively dancing anymore, but would anyone mind teaching me the technique?” I learned so much about musicality and gesture and simplicity from them.

Ito set up a dance technique that was based on different arm movements juxtaposed to simple walking patterns. In a very simple way he was playing with musicality and form at the same time. Often artists are just using music as an environment to move in. I started realizing how powerful it is to connect movement and music, or at least [how powerful it is] to have the option to.

Guernica: Who else shaped you as a choreographer?

Dana Tai Soon Burgess: Years ago I worked for John Neumeier in Hamburg at the Hamburg ballet school. I taught workshops for their advanced students. It was a huge eye-opener for me to watch John Neumeier work. I hadn’t seen a choreographer supported at that level before. He’s working in a major opera house. When he walks into his studio, he has his videographer, his notation person, his cast, his understudies, and he’s got a rehearsal director. It was unbelievable that a choreographer could have all that support.

The way that he worked was so free yet so tied to the music and the storylines he was trying to create. I think one of the biggest limitations for an artist is not being able to dream a golden dream. We’re always saying, “Oh, we can make do with this,” or “We can problem-solve this.” But [Neumeier’s] creative process was very different from piecemealing. It was the first time I understood I could build something larger and that it could be and should be supported.

Guernica: Dancers use the word “gesture” a lot. Can you define it, for non-dance people?

Dana Tai Soon Burgess: Gesture is movement in the hand and arms that conveys a specific emotional motif. Gestures can come up over and over again and they start to become recognizable as a language of their own.

I like looking at invertebrates for movement. One of my favorite gestures is what I call “the squid.” The fingers open and close like tentacles and the wrists push upwards. I also like gestures that are very human, like touching the heart and reaching to another dancer for connection. I love looking at representations of saints: the hands are so symbolic.

DTSB&Co In Concert Series: Tracings from dtsbcodance on Vimeo.

Guernica: One of my favorite pieces is “Leaving Pusan,” which is an excerpt from your larger piece “Tracings.” It’s based on the story of your Korean ancestors, who came to the United States to work at a pineapple plantation in Hawaii. Can you tell me about the process for creating this piece?

Dana Tai Soon Burgess: I wanted to create a work that would honor my lineage. My initial idea was to show the psychological moment when my grandmother made the decision to leave Korea and venture to a new land. I started with the idea of ancestors as ghosts dressed in white, which is the color of Korean mourning. In the dance, they are spirits that guide my grandmother to safe passage to Hawaii. Then, I developed the motifs in the studio. During rehearsals I asked the dancers, “What if all you could take in a small suitcase were your hopes, dreams, and memories?”

I chose the Korean mask because it is a traditional folkloric dance mask representing a young unmarried woman. The white cloth is a reference to the cloth Korean shamans cut with a dagger in a ceremony to open the portal to the spirit world. The suitcase references the baggage that we always carry with us through life from our families.

Guernica: The folkloric mask appears in the beginning of the piece and then disappears. As the grandmother figure tries to integrate into American society, the mask suddenly appears on her face again. Can you talk some more about this motif?

Dana Tai Soon Burgess: As a child I always loved traditional Korean masked dances. There is something magical about a mask because we all wear or hide behind a metaphoric mask, and ultimately underneath this metaphor is our true vulnerable core. I think we all want to reveal ourselves but can only do so when we feel we are safe.

Guernica: You’ve performed dances about the Asian-American experience all over the world—what has the response been like?

Dana Tai Soon Burgess: It’s interesting. In Peru, audience members came backstage and told me how they understood the journey of Asians to the US because there was a parallel wave of agricultural immigrants who were brought in to work plantations there at the turn of the last century. In Ecuador, people said they understood the woes of working the pineapple fields because they also have a pineapple history there.

Guernica: What are some misconceptions that you’ve had to face as an Asian-American choreographer?

Dana Tai Soon Burgess: There’s this assumption that being Asian American makes it easier for me to get a booking, which always makes me laugh. If you look at how many slots a curator has—there are some slots for international or Asian-American work (which will probably go to the international work because it has more funding), and then the other slots might be for more mainstream companies, like a Paul Taylor or an Alvin Ailey. There are actually fewer slots for a uniquely Asian-American choreographer. There is no lucky diversity card that gets you a better booking than anyone else.

Guernica: How do you make a dance feel coherent and understandable to a general audience without relying on language?

Dana Tai Soon Burgess: The issue is to try and find certain themes that resonate with people and that they start to recognize—whether it’s love or loss or looking for a home—and then to convey those through the movement. I love to have movement flow off of the stage and then stop in an archetypal pose. Sarah Kaufman describes it as almost like origami, where it folds and unfolds, and I love that because I think it’s true.

I often look at the sections of a dance as a map, or like parts of a larger mural. It’s very common for me, in trying to put together different smaller dances into a suite, to play with the sequence until there’s a logic that makes sense.

Guernica: How do you transition between sections of a dance?

Dana Tai Soon Burgess: One of the hardest things in choreography is transitioning between major sections. The transitions are so important—they allow the audience members to continue on the journey with you without jolting them out of the fantasy world that’s been woven for them. When the transitions aren’t making sense they feel rushed, or contrived.

I often bring non-dance people into the studio about three-quarters of a way through the choreography process and ask them what they think they just saw. I find that really helpful.

Guernica: How do you know when a dance is done?

Dana Tai Soon Burgess: It’s so subjective. A dance feels finished to me when I suddenly see this moment in the movement that feels like closure and makes me want to cry. And then I’ll realize, “Oh, that’s the end. This whole thing is working because it all led up to this moment.” It pulls all this together and it sends the correct message in a very poetic way.

Guernica: Some people criticize dance for being elitist and inaccessible. Do you worry that your performances cater to a particular socioeconomic class?

Dana Tai Soon Burgess: No. All of our performances and open rehearsals at the National Portrait Gallery are free. When you look at our demographics, half of our audience members are under forty and come from very diverse backgrounds. We’ve always kept ticket prices low as well. That’s one of the things that modern dance can do—we can keep ticket prices low because we don’t have huge unions the way music does. We have much more ability to reach new and sustained audiences.

Guernica: Have you made a conscious effort to make your dances more accessible to the general public?

Dana Tai Soon Burgess: I never gave up the idea that beauty, the sublime, and the poetic speak to all audiences. We somehow inherently recognize good art versus art that is trite or contrived. I am interested in engaging audiences to probe their own life experiences. In this way I care very much about the audience, but I don’t pander to them. I believe we are on the same journey and I want to create change and provoke self exploration.

I don’t understand choreographers who say they don’t care about the audience or that they would be happy to present their works non-publicly. I think dance is a form of communication and the goal is to dialogue with the audience. If an audience member tells me they cried or that the dance moved them to think about their own journey or a family member’s, then the work is successful.

Guernica: How has your choreography changed over the years?

Dana Tai Soon Burgess: In the beginning, all of the works were very focused on the Asian-American journey, and then they became more about new American perspectives in general. That expanded to the point where we are today, which is more about the American tapestry and what’s going to bring us together. I just finished a work that premiered this past fall at the National Portrait Gallery called “Margin.” The work focuses on issues facing all American communities today: issues of socioeconomic disparity, immigration, race, gender, and sexuality.

The next work I am creating opens in July at the NPG and is based on the Face of Battle-Americans at War 911 to Now exhibition. It will focus on the human and psychological costs of ongoing wars.

Making this shift expanded the cultural and creative journey that I am on and opened me up to further exploration of personal stories and historical events. All people share the same desire to be treated equally. We all go through similar emotional journeys from love to hate, rejection to acceptance. I think the most important thing for dance right now is to allow for more empathy and understanding between people of different races and socioeconomic statuses. In our society we need to build bridges.