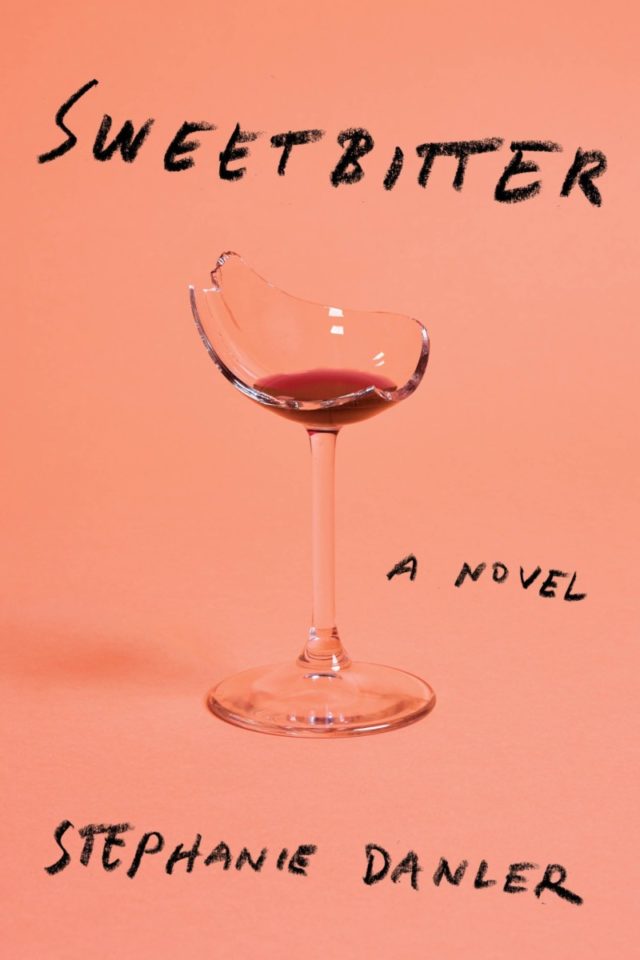

In Stephanie Danler’s new novel, Sweetbitter, her protagonist, young Tess, moves to New York at twenty-two, driving away from a muted Midwestern past, her only ambition is to begin a life, a real one, one that is vibrant and exciting. She finds it in the belly of Union Square, at the best restaurant in New York, where she’s hired as a backwaiter, and taught how to identify an oyster, recognize the grapes of each wine, and get what she wants. She steps into place among the orphans of the restaurant and falls into a complicated infatuation with both Simone, a veteran of the restaurant and an expert of wine, and Jake, a beautiful, complicated bartender.

Danler herself moved to New York after graduating from Kenyon College, where she found a career in hospitality before enrolling at The New School for a graduate degree in writing. I remember hearing her read at the MFA thesis readings in 2014, the year she graduated. Every writer reads about a page from their manuscript: it’s a long night, with a lot of readers, and Danler was someone I hadn’t met. But I can still remember the passage she read: the oyster Tess tries in the walk-in, the description of Jake flipping the shell open with one quick movement. Her poise and talent were immediately evident, and when her novel began circulating I knew I had to read it.

Sweetbitter is urgent and heady, written with great attention to both environment and inner life, detailing desire and intimacy and the navigation of lust. The descriptions of life inside the restaurant are every bit as exhilarating as the lush descriptions of food throughout—heirloom tomatoes and Kumamoto oysters and endless Sancerre. She vividly captures a teetering moment of life, between adolescence and adulthood, when you know less why you want something, than that you just want it so badly it feels like a need. On a rainy day in the West Village, we met for cappuccinos at Via Carota, and talked about developing an awareness for food, investigating appetites, and the importance of saying no.

—Kyle Lucia Wu for Guernica Daily

Guernica: When Tess moves to New York and starts at the restaurant, she has really no awareness of food or having a ‘palate.’ Did you, like Tess, come to food late in life?

It was shocking when I got here and I saw that the restaurant industry was a valid way to make a living and people had real careers in it.

Stephanie Danler: There are two stories there—one is my story, and one is what I was doing with Tess. Tess was emblematic of kids in the eighties who were brought up on microwaves, takeout, and fast food. My peers and I experienced this disconnect from food too. We associated food with going out to eat, but even then not with access to the kinds of restaurants [in New York]. Tess basically has a child’s relationship to food. She doesn’t know how to cook, people feed her, she’s gotten by—it’s sustenance. I had worked in restaurants since I was fifteen years old, so I had an awareness of food that Tess doesn’t have in the book. However, I had no concept of food culture, which was just budding in 2006. It was shocking when I got here and I saw that the restaurant industry was a valid way to make a living and people had real careers in it. My first restaurant job was right in the [Union Square] Greenmarket. My first real moment of awareness with food was similar to Tess’—it was an heirloom tomato and I had never tasted anything like it. I grew up in Southern California where we had tomatoes year-round, strawberries year-round. But the intensity and impact of a piece of food in its peak season after everyone has been waiting for it, which gives it so much energy—that was an epiphany. I wrote something similar but not exact for my character. Tess’s awakening is even broader—it’s across the board. She didn’t grow up in a city, she didn’t have access to food, and she’s never really had the kind of autonomy that living in a city gives you. That awakening of her palate is [emblematic] of all the areas of her life.

Guernica: Tess says it’s hard to know where everyone’s from because it seems like everyone was born and raised in the restaurant. She’s only asked once where she is from, toward the end of the book, and it’s by her drug dealer. Why was it important for her, and everyone, to have minimal backstory?

Stephanie Danler: That’s a choice, like everything, when you’re writing a novel. I really wanted the book to be true to both the experience of working in a restaurant, and the experience of moving to New York. There is this moment when you cross the bridge or you land at JFK where you’re starting over from zero. You have to prove yourself and start at the bottom. It is a place where the American dream still works like that, to some extent. That was one part of it: I wanted her to leave her old life behind and this is the only place that you can go in all of the United States where you can freshly reinvent yourself, where you can be anonymous and then become someone. There are a lot of initiation rites, and that applies to the restaurant industry and to New York City. Part of that is losing the identity that you’ve had before and being given a new one. That happens when you join the military, or when you join a fraternity or sorority, and it happens when you start at a restaurant: you get a nickname, you get a new set of clothes, you learn a new language. You become a new person. I really found her backstory to be irrelevant to this story that I was telling. My experience of working in restaurants for so many years is that we know these little things about each other; we can tell when someone’s mood is about to turn, or if they’re hungry or tired or cranky or what direction they’re going to get up from the table, but we don’t know these essential facts about each other. It makes this incredible intimacy that’s very temporary, and particular to the restaurant industry.

Guernica: I thought her relationship with the restaurant functioned almost like a romantic one, which was very fitting in a book that deals so much with desire. What did you want to explore about desire?

Stephanie Danler: I think when you are investigating appetites, it’s a pretty easy leap from food to lust. When you’re talking about lustful people—I don’t necessarily mean physical lust, but people that lust for experience and for flavor and for intensity—you’re going to cross over into physical lust. As well as a lust for intimacy, which is something that Tess is struggling with the entire time. When I think of the book, I think of a coming-of-age story first, and desire is so much a part of that, how she negotiates real desire in her process of becoming. When you learn I want this and here’s how I get to this and here are the consequences—that’s becoming yourself. That’s how she’s moving from being a girl to a woman.

I do think that restaurants in general, like most industries, are still pretty sexist environments. I think that women in restaurants feel a lot of need to prove themselves.

Guernica: The book also explores how Tess navigates the desires of others—how she is related to differently for being a young, pretty girl, and how her own behavior changes in regard to that throughout the book.

Stephanie Danler: I do think that restaurants in general, like most industries, are still pretty sexist environments. I think that women in restaurants feel a lot of need to prove themselves. The kitchen especially is a boys’ club and a hard place for her to navigate throughout the novel. Like I said, this book is so much about becoming a woman and making the choices that turn you into a real person. I think that’s what most people move to New York wanting to become, even if they have other specific dreams. Part of that process is taking her power back after being told what she is for so long. As a young woman you’re told, you’re the new girl, you’re ditzy, you don’t know what you’re talking about, you’re dismissible—she spends so much time apologizing for the first half of the novel. She doesn’t really have a voice. She doesn’t make a 180-degree transformation because that’s not real life, but by the end she’s able to talk back to people in those final scenes, and I thought that was a mark of taking her power back.

Guernica: Likability seems to be a theme throughout—especially for the female characters, and I think that obstacle is especially potent with Tess.

Stephanie Danler: Well, part of the service industry is being in this position of subservience, making a living off of tips and essentially being likable. It puts you into this dynamic where you’re always trying to make things easy for the people around you. There are a lot of scenes where Tess is dealing with people and she quiets herself or she shrugs out of the way or she apologizes. By the end of the book, when she’s sitting at the Grand Central Oyster Bar trying to read and she’s able to talk back to that man, she’s moved past the point of caring if she’s liked or not. That is something I still struggle with and I think it’s something that all women struggle with all the time. I always think that is the one lesson of my twenties: I learned how to say no. It seems so minor, and at the same time it’s the most powerful thing. Tess is only going from twenty-two to twenty-three, so she’s not making leaps and bounds, but those subtle shifts are really important to me.

What Tess doesn’t realize is that adults are damaged. They’re real people. There’s a process of realizing that your parents are flawed human beings and can’t necessarily be trusted.

Guernica: What’s the most important relationship in this book?

Stephanie Danler: I don’t think readers always agree with me, but I see the central love story to be between Tess and Simone. This yearning for a maternal figure, a familial relationship—for family. It’s really what has driven her into the restaurant to begin with. They are all orphans. They all don’t have a past. Even if they have parents, most people who come to New York keep distance between them and their family. The one she latches onto the most is Simone, who I think loves her in her own way, but what Tess doesn’t realize is that adults are damaged. They’re real people. There’s a process of realizing that your parents are flawed human beings and can’t necessarily be trusted. And of course, Simone’s not her mother.

Guernica: That relationship struck me the most, too.

Stephanie Danler: I love Jake, I love her friends, and I love the story of her and the restaurant—I like the idea of it being like a relationship, it’s very beautifully put—but I do see the central line between Tess and Simone.

Guernica: When you got to New York, you were originally going to go into publishing, right?

Stephanie Danler: Yes, I went to Kenyon College for undergrad and I moved to the city with a group of people from Kenyon. Everyone moved at the same time and everyone was getting assistant jobs, which is what we were bred to do as art majors. The starting salary was like $24,000 and I thought, nope, okay. The parents of my boyfriend at the time gave me a Zagat guide, which I didn’t know how to read. I didn’t understand what it was, but I saw Most Popular Restaurants in New York City and I thought oh, perfect, I’ll just go to all these restaurants—was very naive about New York City dining. It’s so funny to think about what I wore when I dropped off my resume at Per Se. I never got an interview there, but Union Square Cafe worked out, and it changed my life.

Guernica: Your book deal story has really taken on a life of its own, I’ve seen it in so many different variations.

Stephanie Danler: It just depends on what aspect of the story they’ve chosen to focus on. Some people choose to focus on the fact that I was in graduate school and had this amazing agent and we were sending it out to many publishers and some people choose to focus on me waiting on Peter [Gethers, of Knopf]. It’s all the same story, it just depends on the gloss that they want to put on it. I finished school, I had a first draft finished when I graduated, I went to Byrdcliffe [an artist residency in Woodstock, New York] and I revised my novel. I got an agent and we made a plan to send it out. I took eleven meetings with different publishers. It was a crazy, crazy week. But during that same period of time I waited on Peter. I’d been waiting on him for years, and it had never come up. Then it happened to come up, and I got him the manuscript, and that was the magic. I don’t want to take anything away from this story of me sliding my manuscript across the table mid-shift, that never happened, but it was magic.