I didn’t hear any sounds coming from inside my neighbor’s house, so I stepped back to set down my gift. As I bent over, the door swung wide, spilling cool air into the afternoon. A statuesque woman filled the dark entrance. Grey hair, dark and heavy as a thundercloud, swirled around her face. I thrust my flowers at her—I’d bought them for her eighty-fifth birthday—then started to retreat even as she dipped her nose in the blossoms. But my neighbor ordered me back. She propped the screen door open with her hip: “Come in. We’ll have a chat.”

I followed her into her living room. I didn’t really want to talk. Being new to the neighborhood, I’d wanted to be nice, but I’d hoped she wasn’t home so I could just leave the flowers. As I perched on a threadbare chintz sofa, she said, “Do you know how your house was made? How they built adobe homes back in the fifties?”

My house is a traditional adobe, made of the original stuff—a concoction of mud, sand, clay, and straw—used in ancient building to grab energy from the sun. Adobe walls expand as they absorb heat, then contract when temperatures drop, pushing warmth into rooms in a type of convection. Cultures around the world have used the readily available materials for adobe to heat and cool living spaces for millennia, especially where temperatures fluctuate wildly, as they do here in the high desert of New Mexico.

My neighbor said the builder made the adobe bricks offsite then delivered them to the construction site. Workers mixed batches of mortar on the spot. “I used to stand on the street and watch them work,” she said. I pictured her as a young woman in a house dress, a sturdy arm flexed at her hip, hand shielding her eyes, dark hair swirling in a tempest around her shoulders. “Your house was made the old way,” she said. “One shovel at a time.”

I tried to imagine the scene: a team of men working in a line, perspiration beading foreheads, hair spiked with sweat and mud. The man on the ground digs the head of the shovel into the slop in the wheelbarrow. He yells up to the wall, shifting his grip to heave the cargo skyward. The worker on the wall grabs the shovel from the air, a dark silhouette against the bright sun.

In Albuquerque the sun shines 310 days of the year. If you stand at the base of the Sandia mountains, most days you can see clear to Mt. Taylor, a snow-capped peak a hundred miles west. An optical trick of the atmosphere plays the colors of the mountain against the mesa, magnifying the far peak while blurring closer details so the brimstone rubble of the dead Three Sisters volcanoes fades to a lackluster brown. You can’t see Sky City, an ancient village on the mesa fifty miles away; its sandstone homes vanish into the land unless you’re right at Acoma Pueblo. The shimmer of the Rio Grande is the only constant amid this shape-shifting landscape. Somewhere in the river valley, my adobe home absorbs the heat of the day as the fierce sun blazes in a flame blue sky.

That sun could supply energy nearly every day of the year. New Mexico is a small state, with a population of just over two million. Yet a pittance of state energy comes from solar, with five arrays—little seas of blue silicon that flash among the brown mesas—producing 150 megawatts of electricity. For comparison, the largest coal-powered plants, Four Corners and San Juan, generate 2100 and 1643 megawatts of power, respectively. Even here in the sun-drenched Southwest, utilities are still digging under the skin of the land, burning the bones and blood of it to heat and power homes, hacking through mountains for coal, or puncturing deeper into the earth for natural gas—like heroin addicts prodding for a good vein. Despite the constant sun’s promise of local energy, my government keeps exporting men and women to distant nations to fight for access to dwindling oil hidden beneath the sand.

I do not work, I do not eat, I do not wake without the steady flow of electricity coursing through my walls. I can’t live without it.

My husband, whose education was subsidized by the Army, deployed twice to the Middle East. There the sun glares down as steady and accessible as here in the Southwest. Lee spent nine months in Iraq sedating soldiers injured by explosives. He doesn’t talk much about the trauma he saw there, but he once recalled how he’d see young men, first thrashing with pain, who would then calm for a moment to bellow a disbelieving “Motherfucker!” on discovering shredded muscle and tendon hanging where a desert combat boot used to be.

It was nine at night when Vipin Gupta called to talk about his research. In the local weekly, I’d read about a project at Sandia Labs and contacted Gupta, a solar researcher. Sandia is affiliated with the US Department of Energy, where 40,000 scientists, engineers, and staff study bioscience, energy, and weapons. The lab is also a subsidiary of Lockheed Martin, which makes me suspicious of their research—how much of their work benefits the greater good versus the great capitalists funding it? My suspicions may be misplaced. The scientists at Sandia dreamed up micro-encapsulated photovoltaics, or solar glitter: they’ve shrunk down solar panels so you can hold one on the tip of your finger. Vipin Gupta is something of an evangelist for solar, a humanist researcher who talks about establishing a more egalitarian approach to energy: along the lines of handing control back to the people. He was driving back from a conference in California, so as I padded around my house with the phone, he warned me he might lose me in the mountains.

“With the size of micro-encapsulated cells, you could put solar anywhere,” Gupta explained. He hoped a glitter aesthetic—unobtrusive cells or cells as a smart design feature—might convince construction companies to integrate solar into buildings. Gupta described weaving tiny solar cells into fabric or molding them to any form. A flashy promo video online illustrates these ideas, with Sandia researchers rattling off a long list of options: solar designed into architecture, cars with glitter bound into the frame, and clothing that recharges batteries.

Electricity is woven into the fabric of my convenient life. Despite my adobe walls, I raise the heat in my home, retreating from unpredictable weather into a temperature-controlled room. Light guides me through the dark, offering safety, letting me stretch time to my demands, to work and play in unnatural cycles until the sun returns. I store exotic foods in a cold metal box charged by a constant electric current. I do not work, I do not eat, I do not wake without the steady flow of electricity coursing through my walls. I can’t live without it.

My neighbor brought me black tea in a flowered porcelain cup and hard biscuits on a matching saucer. As she slurped her hot tea, she described the family who’d lived in my adobe home for over half a century; she recounted neighborhood scandals that had died decades before. Soon she fell to reminiscing over her years studying Navajo at the University of New Mexico. “Back when they still taught Navajo,” she said. She peered at me over her teacup, the far edges of her eyebrows quirking up: “It’s not an easy language.” UNM still teaches adobe construction, though; the school hasn’t abandoned all of the old ways.

Days later, I pressed a hand to the walls of my home and felt its cool breath on my palm. I stepped back to measure the girth of a post, touching my thumbs together then fanning out my fingers. The wall was as wide as the distance from one pinky knuckle to the other, nearly a foot. In summer, the heft of those walls kept my rooms in cooling shade. One winter when my furnace broke, my rooms stayed a comparatively balmy 55 degrees, compared to 20 degrees outside. Lee and I still heated the house with a gas furnace and, on nights Lee hoped to spark a little romance, a wood-fired kiva. We cooled it with central air, but our mud walls kept utility bills low.

My sturdy walls can’t hold any energy, though; they can’t store away sunshine for future use. The ancient technology behind adobe can only disperse the energy it absorbs. Even the modern technology of solar panels faces the same old disadvantage: can’t store a thing. When photons from the sun hit silicon crystals, those photons make the electrons dance, and once electrons start moving they must keep moving. Electrons will ease on down the power lines wherever demand may take them. So when I switch on my lights, at the local coal- and gas plant, workers simply feed the beast of steam-powered turbines with more fuel to send electrons down the line. You can’t feed in more sunlight at night: there are no electrons dancing in the dark on solar panels.

On the phone, Vipin Gupta discussed his vision for energy, a future where solar glitter is coupled with batteries for storage. Because tiny solar cells could adhere to any shape, you could integrate them with a battery in a discreet system.

But you can store fossil fuels in tanks and bins and barrels. It’s the path of least resistance that a society of convenience prefers.

“Think of the cells as building blocks,” Gupta explained. “They’re very small and you can use them in any way you can imagine.” He asked if I ever owned a solar calculator. I laughed, admitting I still had the one I’d used back in high school more than twenty years ago. “And it still works, right? On that calculator you’ve got a layer of cells probably one centimeter by one centimeter.” The cells don’t get in the way, but they take up real estate. With solar glitter, cells could be almost invisible. “You could put them between the keys. You don’t even realize they’re there.”

Energy researchers have had over half a century to solve this storage problem: photovoltaics have been around since 1954, when scientists at Bell Laboratories first coaxed an electric jolt from a solar cell. Even Einstein put his mind to solar before turning to the big bang of nuclear. We’ve pumped oil and shoveled coal into our homes since the 1880s, but we’ve used natural gas only since the 1950s—about the same time photovoltaics research began. Much of the appeal of fossil fuels—coal, oil, and gas—is that they’re easy to store. But they’re not easy to extract, process, or transfer. They’re not necessarily cheaper than solar—factoring in government subsidies, tax incentives, artificial pricing structures, trade agreements, and transport. Climate scientists link burning fossil fuels with Nor’easters in October, drought in California, rising sea levels, shrinking aquifers, and ironically, enough ice melt around the Arctic Circle that countries can drill for more oil and gas. But you can store fossil fuels in tanks and bins and barrels. It’s the path of least resistance that a society of convenience prefers.

Vipin Gupta’s voice bristled with frustration. “Look at the history of man and energy. We went from chopping down wood to harvesting whale oil. We were killing creatures to harvest their energy,” he said. “Then we went underground for oil, for natural gas. We’re making a deal with the devil. We are digging to hell to get our energy source. It’s brought out the worst in humanity. The places where we find oil have dictators. They have the worst human rights records. Without even going into the environmental effects, we are on track to create hell on earth.”

Through solar research, Gupta hopes to return the country to a more democratic relationship with energy. “We advocate harvesting energy from above,” Gupta said. “The amount of energy from the sun dwarfs the energy from below. If we could harvest all the sunlight that falls in one hour, we could meet the needs for all of humanity for a year. We just don’t have the ability to convert it to the energy we need yet.”

Before we bought our home, Lee and I had the chance to talk with the architect’s son about his father’s methods. During the mid-century boom, while other builders hammered up neighborhoods of plywood ramblers, P.G. McHenry championed energy-efficient homes built of local mud and clay. He traveled the Southwest and the Middle East, learning ancient building techniques and guiding others in modern adaptations for adobe.

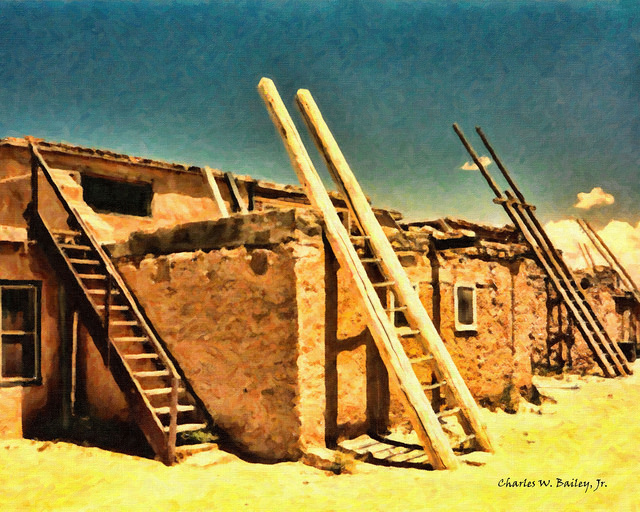

Scattered throughout the Southwest, adobe ruins trail down to Mexico and north to Colorado: remnants of the Anasazi, peaceful people who once inhabited the mesas. Anthropological evidence shows the Anasazi leaving the plateaus over time and scrambling into the cliffs, building homes higher and deeper to protect themselves from… what? No one is certain, though historians speculate predatory rivals forced the quiet Anasazi into hiding. They disappeared, the Anasazi story faded into legend, and most of their adobe homes crumbled back into the earth. The Acoma descended from the Anasazi, so when I learned that Sky City at Acoma Pueblo, a historic village atop a mesa, was just an hour outside Albuquerque, I had to drive out to the site. I had to walk the village, to press my palm to sun-baked bricks—so like the bricks in my own home—which had gathered sun for nearly a millennium.

At Sky City the September sun beat down mercilessly. Exactly one tree grows on this sandstone plateau. “We call this tree the Acoma National Forest,” said our guide, Susie. Sky City was not what I expected. I thought the village would be locked in time, like tourist Pilgrim towns in the Northeast. But families have lived here continuously for centuries. It’s a functioning village like others near Albuquerque, if a little more rustic. I’d expected centuries-old gates and melting glass (or no glass at all), because I’d forgotten that people live here year round. When I strolled the dusty streets with a tour group, a screen door slammed as a kid ran off on an errand; a window slid on a steel frame as a woman let fresh air into her living room.

Our guide was a tiny plump woman with black hair so shiny and straight the sun flashed off its surface like it was a mirror. Susie told us the Acoma people originally migrated from Chaco Canyon. There it was, the direct claim to Anasazi heritage, which to me meant a direct link to ancient adobe. Except the homes in Sky City were not adobe, at least not all of them. The village was built on sandstone. Rather than baking mud bricks, the Acoma cut bricks from the surrounding mesa. Porous sandstone must be sealed with plaster or replaced as wind and rain nibble it away, a process now accelerated by aggressive weather driven by climate change. Most residents have rebuilt their homes over the years, often with contemporary materials like cinder blocks, concrete, and plaster from Home Depot. Still, some sandstone bricks date back to the 1200s.

With the microencapsulated photovoltaics at Sandia Labs, solar in the palm of your hand means energy at your fingertips, almost anywhere you can imagine.

Like any neighborhood, Sky City had a mish-mash of homes along its wide red streets. There was the house of exposed bricks where straw poked from the mortar around the window. Right beside I saw a house nearly identical to mine—white territorial frames, double-glazed drop windows, and stucco tinted a bright terracotta. At the edge of the mesa stood Mission San Esteban, a behemoth church established in 1641 built with nine-foot thick adobe walls. Our group filed into the empty nave with its clean-swept earthen floor, and the space felt as cool as any air-conditioned convention hall.

I was awed by the massive adobe church and by homes that had survived this mesa since 1250. Susie pointed out the giant bread oven where villagers still bake sopapillas for feast days. She gestured to a stairway carved into the sandstone cliffs, where women once carried water from an underground spring, balancing pottery jars on their heads. But a glimpse of something unexpected made me consider the future of Sky City rather than its past. Susie showed us the new bathroom facility, tucked behind a boulder. A glint of blue flashed off its rooftop, two solar panels angled south. The Acoma are running water pumps for plumbing, powered by solar, instead of delivering and removing the honey pots that had served as their facilities for decades.

How could advances in solar technology impact Sky City’s self-sufficiency? Would the Acoma use solar to heat water as they use gas generators now? Would they turn to solar to light their homes? With the microencapsulated photovoltaics at Sandia Labs, solar in the palm of your hand means energy at your fingertips, almost anywhere you can imagine—even on a mesa dozens of miles off the electric grid.

For the moment, those who want to grab the sun’s energy must buy or build adobe or prop big, rigid solar panels on a rooftop. Which means people must make the most of what’s available. Which can mean taking advantage of the size of solar panels, as the much-maligned Veteran’s Administration did in 2010.

At the hospital where Lee works—Raymond G. Murphy Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Albuquerque—administrators realized the blistering parking spaces surrounding the hospital could serve a higher purpose. With funds from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, the VA installed solar arrays over three parking lots. The panels made shade for patients and staff while generating energy for the building. I like pointing out that staff in New Mexico hoisted their solar panels over VA parking lots long before the folks in California—it took three more years before California VA hospitals installed their arrays. The Albuquerque project cost $20 million for a 3.2 megawatt system, enough power to shoulder 20 percent of the hospital’s energy load from just three parking lots. The sun helps run lights, computers, air-conditioning, and life-saving machines.

My husband is not quite the liberal I am, but the VA solar project impressed him. He reminded me, however, that the project worked backwards. It reaped benefits from a renewable, domestic energy source at a hospital treating soldiers who had already put their lives on the line for foreign fossil fuels.

While many of the aging patients Lee treats at the VA served in Vietnam and Korea, younger veterans served in the Gulf Wars. They bear the visible damage of modern warfare. Veterans of conflicts in the Middle East are missing arms and legs because Kevlar body armor protected their hearts and guts from explosions, but their hands and feet got blown away. These men and women gave their blood and body parts for oil, for energy, for our convenience. Now, when they visit the VA for treatment, they can park their cars in the shade of solar panels that served them too late.