By Shaj Mathew

Ten years after his death, the craze over Roberto Bolaño appears to have subsided. The Third Reich, serialized two years ago in The Paris Review, met largely tepid reviews. Critiques of Woes of the True Policeman regularly ascribed a mixtape quality to the work. The New York Times called it “a collection of outtakes” while The New Republic argued that “the continued publication and popular packaging of his incomplete work may actually be diluting his reputation as a writer of varied talents and fearless ambition… We have enough.”

These disappointing, occasionally strident reviews might normally discourage the release of even more of Bolaño’s writing but a recent exhibition of his unpublished manuscripts, photos, letters, and even web history makes an extremely compelling case for exactly that. “Archivo Bolaño,” which was on display at the Barcelona Contemporary Culture Center (CCCB) earlier this year, was curated by Valerie Miles, the editor of Granta en español, and Juan Insua, a veteran curator at the CCCB, with the collaboration of Bolaño’s widow, Carolina López. The exhibit attempts to set the record straight on the life of a man who embraced, and even cultivated, myths about himself. Did he actually do heroin? (No.) Did he prefer poetry to fiction? (No: “We’re less young every day, fortune with some, poverty with others: I write verses, dream of a novel,” he scribbled in a notebook from 1978.) Was he in Chile during the Pinochet coup? (Nope.) While the literary community may be experiencing Bolaño fatigue, López and the curators felt that these speculations about his work and life deserved the more critical take offered by their exhibit, which charts three separate stages of Bolaño’s literary development during the years he lived in Catalonia (1977-2003).

“He had the sense that he was doing important work. He was a packrat. He kept everything in order. He was organizing his archive.”

“We’re trying to reorder some of the myths based on the documents,” said Miles, who guided me through the exhibit for nearly two hours. According to Miles, who has spent the past four years looking through Bolaño’s notebooks, López wanted visitors to “have a look at the archive and then speak for themselves.”

Despite the minor backlash against a perceived Bolaño overload, it’s clear to Miles that Bolaño wanted his unpublished work to see daylight. “He had the sense that he was doing important work,” said Miles. “He was a packrat. He kept everything in order. He was organizing his archive.” The handwriting in his notebooks, Miles notes, markedly improved during the latter period of his life. Woes of the True Policeman was on his desk, ready to go, when he died. And if there was any further doubt about whether Bolaño wanted posthumous attention, consider this scene from one of his notebooks from 1983, in which a woman discovers a set of manuscript pages in a bookshelf drawer:

This might not seem like much, but the metafictional significance of this passage (quoted in Miles’ essay, “A Journey Forward to the Origin,” from the exhibit catalogue) becomes clear after one learns that the phrase “I’m immensely happy” is all over Bolaño’s notebooks. Simply put, this passage is about someone discovering Bolaño’s archive. “It’s another little Bolaño twist: he’s saying, ‘I’m speaking from the future,’” said Miles, who felt as if she was being described on the page. In that moment of discovery, she was reading Bolaño writing about her experience of reading Bolaño.

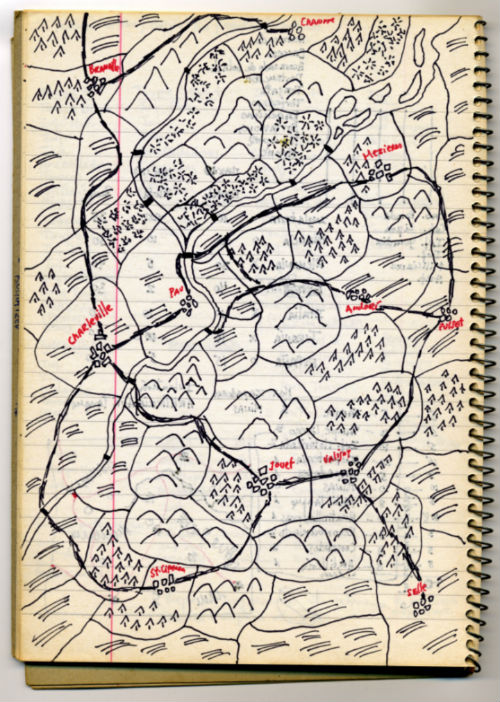

After poring over Bolaño’s notebooks, which also feature impressively sketched self portraits of “San Roberto de Troya,” a nickname he gave himself, and notes of encouragement to himself, Miles and Insua classified Bolaño’s development in Catalonia into the exhibit’s three stages: “The Unknown University” (Barcelona, 1977-1980), “Inside the Kaleidoscope” (Girona, 1980-1984), and “The Visitor from the Future” (Blanes, 1985-2003). In Barcelona, writing by hand, Bolaño developed his voice, doing unusual writing exercises—he wrote stories based on the art on his matchboxes, among other things—to produce different styles. Bolaño found Barcelona too distracting and was unable to publish much, so he moved to Girona where he isolated himself completely and wrote Monsieur Pain and three still unpublished novels on a mechanical typewriter: Diorama, The Spirit of Science Fiction, and DF, La Paloma, Tobruk.

Girona saw the emergence of Bolaño’s kaleidoscopic technique, which produced writing many American critics have misunderstood as a substandard pastiche of his previous work. In particular, Bolaño began to experiment with metalepsis; that is, he began to use characters from his previous works as starting points for new writing. For example, Distant Star emerges from the last chapter of Nazi Literature in the Americas, just as Amulet springs from chapter four of The Savage Detectives. Likewise, American critics have observed that Woes of the True Policeman tells the familiar story of a key character from 2666.

As you walked around peering at the collection, you heard whooshes, cascading waves, foreboding beeps, screams—all of which collectively mimicked the movement, terror, and wonder of a Bolaño novel.

But this is no mere “collection of outtakes,” as the Times would have you believe—Bolaño’s intertextual continuity throughout these works is intentional, for it creates a self-referential literary terrain in which the reader, surrounded by so many recognizable signs and symbols, can arrive at several different readings of the work. Miles describes Bolaño’s kaleidoscopic process, and its effect on the reader, in her essay “A Journey”:

When Miles and I were discussing this in the Blanes section of the exhibit, a man in his early twenties—perhaps a fellow Bolaño disciple—hushed us as he hovered over a nearby vitrine containing Bolaño’s model for 2666. “Too loud,” he said. Miles explained to the man in Spanish that she was one of the curators of the exhibit, but he simply responded, “too loud” again and continued eying the manuscripts. This is what he saw: a very roughly drawn diagram resembling a living, breathing, and wholly unclassifiable organism—at once human and alien, with lines like blood vessels sprouting out of a small, circular saucer. I imagine that these vessels represent the five parts of 2666, which intersect at the saucer, the center that coheres the novel. Think of it as a self-enclosed, self-sustaining environment: each individual vessel or part of the book tells its own story; taken together, these vessels create a whole novel. But the diagram also looks like many other things: A crustacean that evokes the nautical motifs of the Gaudi houses in Barcelona, or a cell diagram. Its ineffability is quite apposite: a novel like 2666 demands a structure equally sui generis, one that recalls some form of life.

“Archivo Bolaño” imparted a tremendous amount of casual knowledge to its visitors: The fact that Bolaño wrote poetry on graph paper, much of which hasn’t been published, and that he actually played the war games that the narrator of The Third Reich loves so much, sending in game pieces by mail. But that was only a piece of the exhibit’s appeal. As you walked around peering at the collection, you heard whooshes, cascading waves, foreboding beeps, screams, a typewriter clacking away, a meow seemingly uttered by a something other than a cat—all of which collectively mimicked the movement, terror, and wonder of a Bolaño novel.

As we ambled out of the exhibit, Miles told me that after Bolaño’s death, the novelist’s widow, López, who was separated from Bolaño when he passed, felt that “people who thought they knew him didn’t know him as well as they think they did.” “Archivo Bolaño” allowed readers to make such a judgment themselves, and in so turning over the reigns to the visitor, inviting them to examine how both truth and myth are constructed, the exhibit further enacted the experience of reading Bolaño. For always Bolaño’s detectives/readers/visitors don’t just interrogate criminals—they interrogate facticity itself.

Shaj Mathew has contributed to the New York Times, The New Inquiry, Sports Illustrated, The Millions, The Philadelphia Inquirer, and McSweeney’s. He attends the University of Pennsylvania, where he is researching Bolaño as an Andrew W. Mellon Fellow of the Penn Humanities Forum.