By Nathaniel Rich

An eerie, enchanted night. Full moon. The devil has just returned from a grand ball held in his honor. He is accompanied by his retinue, among them a red-headed succubus; a giant talking cat, Behemoth; and the devil’s date at the ball, a naked woman he has abducted named Margarita. They gather in a Moscow apartment and prepare to have supper. A candelabra flickers; the fireplace roars. The succubus slinks. The devil sits on the edge of his bed in a nightshirt. Behemoth spreads mustard on an oyster.

To repay Margarita for serving as his hostess at the ball, Satan promises to grant her a wish. She begs to be reunited with her lover, the Master, a writer who is imprisoned in a mental hospital. Soviet critics have pounded the writer into penury and mental anguish. As soon as Margarita makes her request, a wind bursts into the room and a square of greenish light falls onto the floor. The Master materializes.

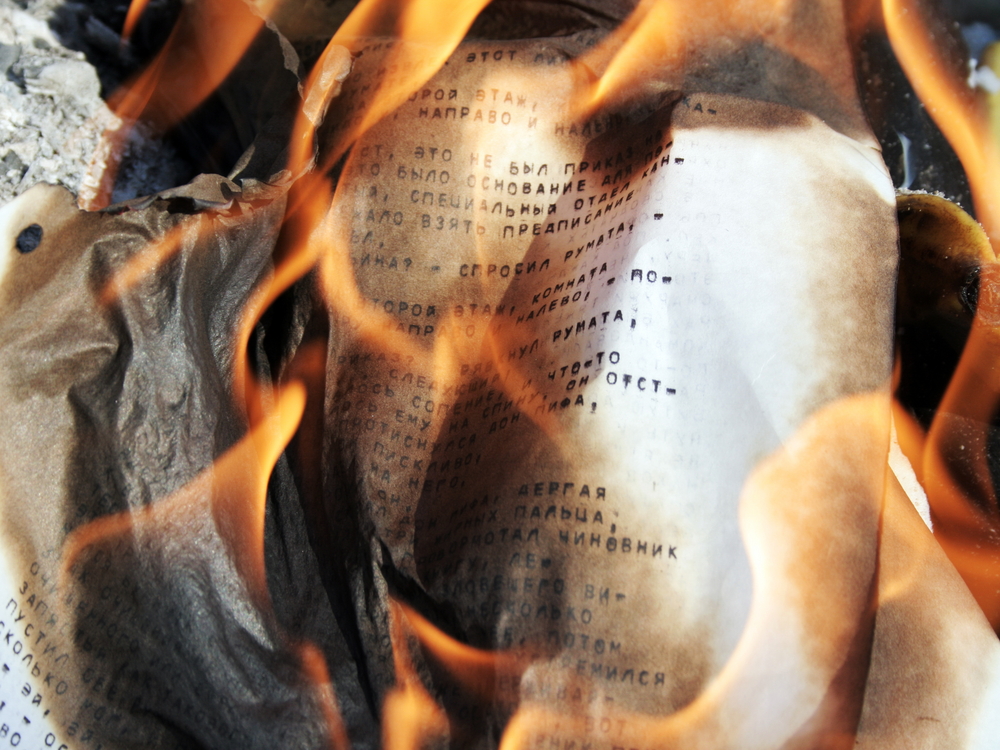

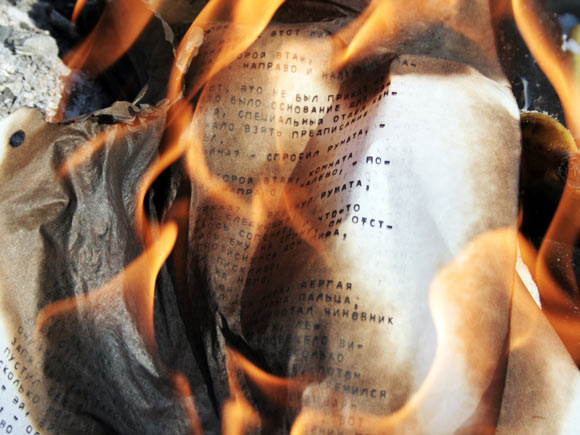

The devil asks to see the author’s manuscript, a novel about Pontius Pilate and the trial of Jesus the Nazarene. The Master declines. “I burned it in the stove,” he says.

The devil doesn’t believe the writer. “This cannot be. Manuscripts don’t burn,” he says. He turns to his cat. “Come on, Behemoth, let us have the novel.”

The cat jumps off his chair, and everyone sees that he had been sitting on a thick stack of the Master’s manuscripts.

It is a magic trick—the devil, elsewhere in the novel appears as a magician—but, like so much in The Master and Margarita, it reflects a bright shard of truth. Manuscripts don’t burn. Great literature, Bulgakov is saying, is fireproof. It survives its critics, its censors, and even the passage of time.

Events in Bulgakov’s own life bore this truth out. During a search of Bulgakov’s apartment in 1929, Stalin’s secret police confiscated the author’s personal diary. When the NKVD (the People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs) returned the diary to him, Bulgakov promptly burned it. But 45 years later, long after Bulgakov’s death in 1940, the diary was discovered in the NKVD’s archives. An anonymous security agent had taken the time to copy it, in its entirety.

The Master and Margarita was subject to a similar fate. Persecuted by critics, the Soviet literary bureaucracy, and Stalin himself, Bulgakov burned the original manuscript in a stove. Though he resumed writing the novel, and worked on it for the last eleven years of his life, he kept it hidden and secret. His wife preserved the manuscript, which was finally published in the Soviet Union in 1966, and even then in an abbreviated form; an additional seven years passed before an unexpurgated version appeared. Today, nearly 75 years after the author’s death, The Master and Margarita burns brighter than ever. Its flame has devoured its apparatchik critics, the NKVD, and even the system of government that censored it. A work of genius and light, it remains a blistering reminder that you can’t fight fire with fire.

Nathaniel Rich is the author of The Mayor’s Tongue. His next novel, Odds Against Tomorrow, is forthcoming in April 2013. He lives in New Orleans.

Check out all the pieces in our Banned Books Week series:

Interviews

Sherman Alexie interviewed by Ed Winstead

Katherine Paterson interviewed by Nicole Deming

Alice Walker interviewed by Megan Labrise

Essays