Dickinson’s statement—“When I state myself, as the representative of the verse, it does not mean me, but a supposed person”—is now poetic dictum: the speaker of the poem is not the poet herself, but instead a fictional device around which an aesthetic experience is organized. Given that truth, “confessionalism” can no longer be read as sincere utterance but demands to be seen for what it is: a useful trope for presenting a character’s vexed interiority (the character sometimes built from selected bricks of autobiographical fact).

Ventriloquism is one way to think of such work, with the speaker as the doll on the knee and the poet as the one who holds the doll, both slyly dressed in matching plaid or polka dots. The rhetorical surface itself can heighten the sense of a mask and insist that the experience be seen as an aesthetic one—not as an invitation to crouch down and peer through the keyhole of a closed door behind which a poet lies on the psychoanalytic couch. Poetic discourse becomes the mere scaffolding that covers a building formed of associative content in which the speaker, the poet, and the reader live.

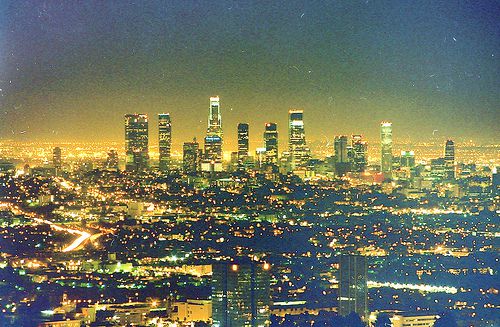

In If I Should Say I Have Hope, Lynn Melnick masterfully uses the trope of poetic confession to create a portrait of coming of age among the dangers and delusions of Los Angeles. If it were prose, we’d call it memoir, but because it’s poetry, the “I” brings to bear not just past fact but sound and language tangled together to make something that never was before, but now is—i.e., a poem, with its sound-dependent subjectivity.

—Mary Jo Bang for Guernica

Mary Jo Bang: What I love about your poems is how they weird the quotidian world, both by wringing all the useless pauses from rifts of description and through odd gothic transformations of the ordinary. Plath, of course, used the latter strategy but her syntax is much less torqued and the sound is more ordered. I find it paradoxical that like Berryman, by adding sonic and syntactical estrangement you actually make the vexed interiority of your speakers seems less lyrically produced, not more. What role do you see sound play and non-normative syntax playing in your poems?

Lynn Melnick: Thank you for the nice things you say! Yes, sound play and non-normative syntax play a crucial role in my poems but not in any planned-out, careful way; after years of practice I have learned to trust my gut and, frankly, this is just how my brain strings words together, and what ultimately sounds correct to me. I feel like I have two voices—one is more casual and never met a run-on sentence or thought it didn’t want to spend some time with. The other voice hears music inside words and just knows by instinct when the sound is correct for the meaning. So I wouldn’t say I employ a strategy, more the other way around. But I stare at drafts of poems forever and ever and change little things here and there endlessly until I’ve settled on the exact sound-to-meaning situation that I need.

Mary Jo Bang: In these poems the non-sentient and the abstract often have agency—a humming generator calls a car to park, rage straps people to their seats—and yet these moments don’t feel like empty pathetic fallacies. They feel like convincing descriptions of how the world works. And they highlight how little power the speaker has and how hyperaware she is. I’m reminded in those moments of both Hopkins and of Dickinson. Are either, or both, of those poets important to you? And if not those, which dead poets are?

Lynn Melnick: Yes, both Dickinson and Hopkins are important to me for many reasons, but, in terms of influence, I have a hard time figuring out how exactly my style came to be. Of the dead poets, I’d have to say Bronte, Rossetti, Plath and Sexton were huge for me, and still are. Also Hart Crane and Dylan Thomas (the first poet I remember reading). I’ve long been wild about H.D., and she is important to me, but I don’t see much, if any, of her in my own poems (I wish I could do that much with that few words). Oddly, too, I find that the Beats influenced my writing probably in a bigger way than I’d like to admit (they were so cock-heavy and are rather out of fashion these days). But they were among the first poets I read (every asshole I fell into bed with as a teenager seemed to have a Beat anthology next to his stash) and I think I internalized quite a bit of that aesthetic (hence the run-on sentence problem) without wanting to admit it to myself for quite a while.

What I mean to say is this: there is the speaker who is all intense and then there is Lynn who is intense but also eating Reese’s Pieces and spilling them out of the bag because she’s an un-poetic buffoon who likes candy.

Mary Jo Bang: The speakers of your poems seem to have a hard-won psychological intelligence. We are taught in poetry school that the speaker of the poem is not to be viewed as the poet herself. Given that the speaker is a construct—sometimes a type, sometimes a ventriloquist’s doll dressed in clothes hand-sewn by the poet—how would you describe the difference between yourself and the speaker or speakers in these poems?

Lynn Melnick: Ah, yes, the “speaker.” Well, I certainly don’t think poems have to be autobiographical in any way, and it can be a frustrating assumption, I’m sure, but I’ll say this: I write about myself. And, yes, things were rough there for a while. But poetry is art, and I get to change details and employ metaphor and get kind of crazy with reality and thought.

What I mean to say is this: sure, certain intense events may have occurred, but day-to-day life isn’t usually one intense moment after another. For example, in the reality behind the poem “Blackout,” which you mention earlier (the generator, the rage), I was freaking out and high as a kite and in a relationship that was violent and doomed. But what I left out of the poem was the bag of Reese’s Pieces I bought at the liquor store we were parked outside (I remember this clearly because I dropped them all over the front seat of the car and because it was the first thing I’d eaten in a while) and also that the power came back on after only about two hours.

What I mean to say is this: there is the speaker who is all intense and then there is Lynn who is intense but also eating Reese’s Pieces and spilling them out of the bag because she’s an un-poetic buffoon who likes candy.

And yet, even as having a book feels like someone stole my diary and is running down the street spewing its contents, the new poems are more raw and more graphic than before. I like to make myself squirm, apparently.

Mary Jo Bang: It seems to me that one way to read If I Should Say I Have Hope is as a coming of age story. A female Holden Caulfield—who speaks in sonically rich, clipped verse—tells the story of an ill-prepared innocent who first gives in to the world’s selfishness and then finds her identity by pushing back against it. Have you ever thought of writing a young adult novel?

Lynn Melnick: I appreciate your saying that because much of the book is about what it felt like to come of age in a female mind and body in California in the 1980s and 1990s, a dangerous thing indeed. And although I’m actually not a huge Catcher in the Rye fan (I think I came to it too late) I understand, and appreciate, the comparison.

I actually have written a novel! It was my side project for years, bit by bit, and then suddenly it was finished, and revised and revised and finished again and etc. I think it could be for young adults, it has a young woman who narrates it, but I’m not sure what the content line is for these kinds of books so perhaps it’s an adult novel that young adults might enjoy. Right now it lives in a metaphorical drawer in my computer. It’s been a surprise, the whole fact of it, and especially because the events in the novel are both more fictional and somehow more personal than my poems manage to be. Maybe this is because the language is more straightforward.

Mary Jo Bang: What are you working on now?

Lynn Melnick: I’m writing a lot of poetry. I was so spun around when my book came out and the only thing that made, and makes, me feel like I have some control over things is to write new poems. And yet, even as having a book feels like someone stole my diary and is running down the street spewing its contents, the new poems are more raw and more graphic than before. I like to make myself squirm, apparently.

Lynn Melnick’s poetry has appeared in Antioch Review, BOMB, Boston Review, Denver Quarterly, Guernica, Gulf Coast, jubilat, Narrative, Paris Review, Poetry Daily, A Public Space, and elsewhere. One of her poems was included in Isn’t It Romantic: 100 Love Poems by Younger American Poets (Wave Books, 2004) and another on a postcard for the O’ Miami Poetry Festival. Anticipated Stranger published a chapbook of her poems in summer 2012. Her fiction has appeared in Opium and Forklift, Ohio and she has written essays and book reviews for Boston Review, Coldfront, LA Review of Books, Poetry Daily, and VIDAweb, among others.

Mary Jo Bang’s most recent collections are The Bride of E and Elegy, which won the National Book Critics Circle Award for poetry. Her translation of Dante’s Inferno, with illustrations by Henrik Drescher, was published in 2012 by Graywolf Press. She has been the recipient of a Hodder Fellow from Princeton University, a Pushcart Prize, and a fellowship from the Guggenheim Foundation. She was a poetry editor at Boston Review from 1995 to 2005 and is currently a Professor of English and Director of the Creative Writing Program at Washington University in St. Louis.

Allison Benis White: The Luminous, Grieving Mind