The moon was as close to the earth as it had been in twenty years. And it was full. As full and as bright as a harvest moon, but this one in March, lighting the pink feathers of the Yellow Pocahontas as they marched their tambourines through the Seventh Ward on St. Joseph’s night in New Orleans.

It was not my New Orleans, but it had been my mother’s, and it had been my father’s Gulf Coast, as it had been for generations before him. Two hundred years my family had walked Louisiana streets, Mississippi streets, streets perpetually washed by the salt of gulf winds and surf, covered in thousands of pieces of broken oyster shells, dredged and strewn. All there, shadows and ghosts, dust in the cracks of the floorboards and scattered pebbles on the shore; their names still known by old men on old streets, their azaleas still growing in what are now other families’ yards.

My mother used to say it was the smell of ozone that she missed most, a smell set free by the cracking of distant lightening, a change in pressure, a shift in power.

All there but me. After the 60s drew my parents west to California, I would be the first of many generations to live outside the reaches of the Gulf. I traveled east first, then west again, until my unyielding desire to make New Orleans and its streets my own—a desire that fought vehemently against the wishes of family, the advice of employers, post-Katrina cynicism, the so-called common sense practicality that ruled the lives of friends—brought me to a pale pink house, the walls and floors and storm shutters standing up against two centuries of storms, on the border of the Seventh Ward and the Treme.

It was there that I stood on my front step in March, wearing a summer dress—sleeveless and loose—the shutters open behind me in the warming spring air that was not yet hot but perfectly, evenly warm, a temperature that lingered, fragrant with the smell of kefir lime trees, buds of gardenia, and overgrown rain-soaked grass and mud, even as the sun began to sink behind the river.

My mother used to say it was the smell of ozone that she missed most, a smell set free by the cracking of distant lightening, a change in pressure, a shift in power. It was the smell of an approaching storm that sent her climbing the branches of a tall oak across the street from her parents’ house on the levee to watch sheets of rain move in across the river. My grandmother would call to her from the house, my mother lingering in the oak to watch how the rain covered her view of the river, inch by inch, until there was nothing left to see but a wall of gray.

My father had told me of the stillness that followed a gulf storm, the power of the quiet often more powerful than the storm itself.

Standing on my front step I knew I would miss the smell of the earth after the storm had passed, after the low spots had drained and the earth could finally exhale, shaking off the weight of water. My father had told me of the stillness that followed a gulf storm, the power of the quiet often more powerful than the storm itself, people slow to trust that they, too, could exhale. It was a smell that signaled possibility.

I knew I wouldn’t live at that particular address long. I knew I may not live in New Orleans long. As much as I wanted it to be home, for as much as I wanted to own that pink house with its ancient floors and storm shutters, as much as I was the product of those streets, that mud, and that water, and felt like it was home, I knew this place would always be more theirs than it would ever be mine. Still, that night, I felt like I could call it by that name.

I stood on my front step listening through the calm, damp quiet of that early spring evening for the sound of tambourines. I was listening through the stillness for a chorus of voices belting high the Miiiighhhttyyy Cooty Fiyo opening line of “Indian Red.” I was searching for my tribe.

As tradition prescribed, their parade route was not publicized.

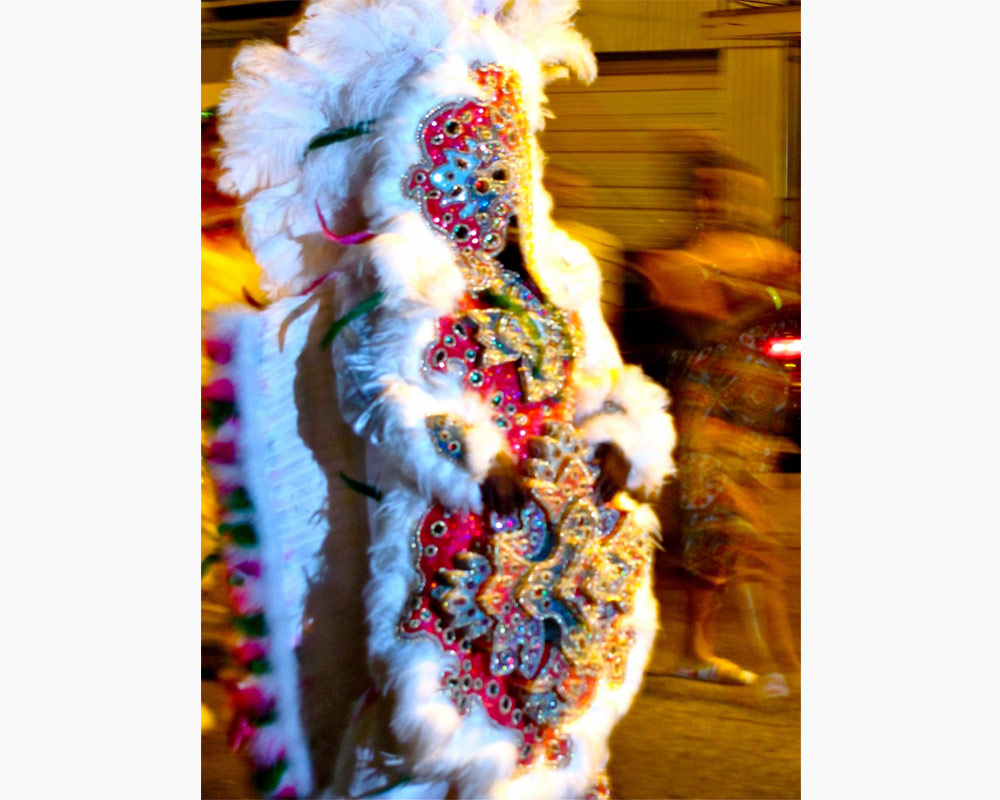

I found the Yellow Pocahontas and I walked with them that night alone, sun-streaked hair in red and white polkadots, a stranger among friends and neighbors, welcomed like I had finally returned home. As tradition prescribed, their parade route was not publicized. Nor was it for any of the roughly thirty-five other tribes of the city who marched that night, and every St. Joseph’s night. The city’s tribes of costumed revelers, called “Mardi Gras Indians,” had once been warring neighborhood gangs, but had evolved—the details of this evolution obscured in myth and mystery—into social groups who honored the masking and suiting rituals of St. Joseph’s night together.

The group was small, not more than twenty to thirty spectator-participants in the beginning, walking behind a tribe of four or five. The further we marched, the larger we grew. We crossed quiet streets where, blocks down in every direction small boys, playing alone in empty, overgrown lots heard the sound of tambourines in the distance and, like cats that pause in motion, lifting their heads to interpret the sound, realized it was Indians and took off running toward our small parade. Block after block, children dropped sticks and basketballs and drum sets, leaving the open spaces where houses once stood to run toward the sound of Big Chief’s song. At the end of the block they jumped wildly with arms in the air, smiles stretching as wide as their cheeks would allow.

“Indians! Indians! Indians! Inddiiiiaaannns!”

The tribe’s bright ensembles reflected this tradition’s many influences: from Native Americans who reportedly “masked” runaway slaves to help them escape bounty hunters, to the passing-down of African and Afro-Caribbean beading and sewing tradition.

They stood on the corner of St. Anthony and Villere taking photos, chanting with the Indians and keeping the beat of the tambourines, Ooo Na Na, Ooo Na Na. We stopped on doorsteps and porches of faces familiar only to those who had walked these streets long before the rest of us and sang to them from the street, beckoning them to leave their kitchens and living rooms and come to the porch, and then into the street, to join us on our walk.

This is the tribe that gave the world Allison Tootie Montana, the Chief who made the prettiest suits New Orleans had ever seen. The suits of feathers and beads are as American as jazz and gumbo, a product of fused cultures, histories, and ancestries. The tribe’s bright ensembles reflected this tradition’s many influences: from Native Americans who reportedly “masked” runaway slaves to help them escape bounty hunters, to the passing-down of African and Afro-Caribbean beading and sewing traditions, to the visits from Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show that brought caricatured Native American influences to New Orleans, to the segregated Mardi Gras celebrations that left African-Americans and Native Americans in New Orleans to create their own celebration. And it was Tootie Montana, as Chief of the Yellow Pocahontas for nearly the entire second half of the 20th century, who insisted on the departure from tribal violence in order to focus on tribal tradition, demanding that bloody knife fights between neighboring tribal gangs who met on darkened streets on St. Joseph’s Night be abandoned in favor of warring craftsmanship, a competition of plumes and elaborately hand-sewn patches of beads.

Pink was the theme that year. A pale, muted pink, made vibrant with the sewn patches of beads and jewels that flickered against masses of feathers and satin. Big Chief was adorned with a pink headdress, as was his Queen, so too his little chiefs-in-training, most not yet four feet tall. All flashing pink satin, pink feathers, pink beads woven throughout the year into dozens upon dozens of intricately cut cardboard shapes and strips that covered each suit, from headdress to boot. Only the Flag Boy dared flash a different color—his suit a royal blue, equal in shine but not in feathers or beads, perhaps preferring the way the pure satin of his suit caught the glow of the moon—as he led the tribe on their annual neighborhood parade.

Oh lil Liza, lil Liza Jane, Big Chief began. Oh lil Liza, lil Liza Jane. The tribe joined in first. The followers, the admirers, and the dreamers caught up in the second line. And we all continued on.

We stopped at the Montana house, quiet and modest, white with soft blue trim. Water spilled from the Queen’s water bottle for those who had come before. We saluted the Montanas, Tootie and his family, those living and those passed on. The Indians danced and flashed their pretty feathers while shouting his name.

We walked further. Down St. Anthony to Marais, the moon lighting streets without the guardianship of lampposts. We marched down streets darkened not by light, but by the passing of storms and time and families who had not yet returned, and help not yet received. And under the spotlight of a post-Carnival moon, the Yellow Pocahontas marched their pretty feathers down those still hopeful streets toward St. Bernard.

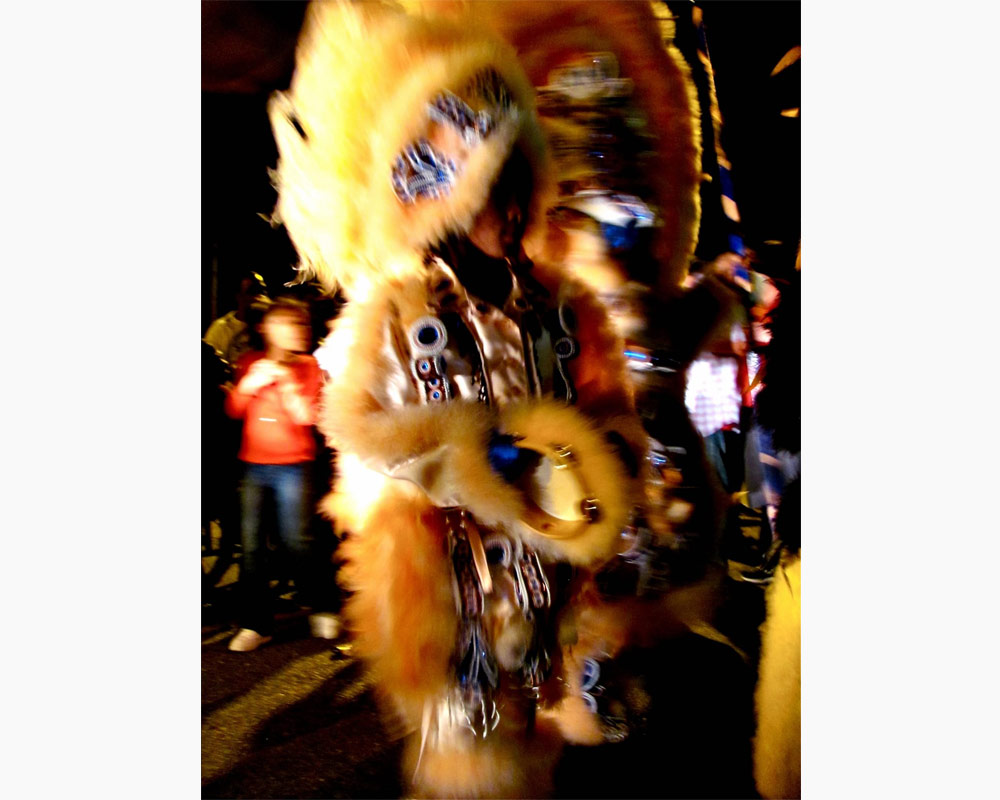

And there, the sounds of tambourines came toward us. Another tribe approaching from higher ground, slowly marching down St. Bernard toward North Rampart. They, too, had their own followers and many more tribal members than the Yellow Pocahontas. Their tribe consisted only of men, one white man dressed in a white suit with blue feathers, their Big Chief, a black man dressed in a suit of black and gold feathers, a Spy Boy and a Flag Boy adorned mostly in beads of gold and white and red. They came toward the Yellow Pocahontas chanting and waving tambourines.

Without warning, the cry of the Flag Boy, the scream of a hawk before it lands on its prey. Crowds quickly formed.

The Yellow Pocahontas paid little mind to that first approaching sound. But as the intruders drew closer, they paused, and then took their positions. Big Chief, at the back of the line, nearly two blocks removed, waited for his Flag Boy to march ahead, the flag of the Yellow Pocahontas held high. Their Wild Man stood between Flag Boy and Big Chief, dancing in anticipation of battle.

Without warning, the cry of the Flag Boy, the scream of a hawk before it lands on its prey. Crowds quickly formed. The tribes stood facing each other, spread out along St. Bernard.

Flag Men rushed towards each other in a flash of color, their flags high in the air, their yelps and cries carrying over the cheers of the followers. This was the historic battle, fought every March 19th, tribes creating their own legacies, continuing the legacies of those who came before. The crowds were so thick that from the outskirts the only sight was that of feathered flags rushing through the air, a rush toward each together, the flags flapping ferociously through the warm lit glow of the moon and street lamps, and then a slower rush away, like the movement of waves thrown ashore. They taunted each other for several minutes, rushing back and forth and dancing violently, their fight now one of movement and of ostentation, showing off their feathers and beadwork until finally the flags were lowered and the Chiefs moved closer. And just as suddenly as they had both formed their battle lines, they smiled, laughed hearty laughs, hugged great hugs of feathers, and gave the signal to the men who followed that their Chiefs would remain safe. Each began complimenting the suit of the other, admiring the intricacies of the sewing, the uniqueness of the design, and the real show of beads and feathers began.

We continued on toward the Treme. We headed over Claiborne East, set for the neutral ground under the interstate. Cars rushed past. Some didn’t see the magic in their pink feathers and tambourines. The sound of speeding cars echoed through the concrete divide where oak trees had long ago been replaced by pillars of cement decorated now with the painted tributes to the oaks, the men, the bands, the tribes of the Treme and Seventh Ward.

Like the hero of a fairytale, he arrived in the intersection to aid the Flag Boy and the drunken man.

The Flag Boy went into the road to stop traffic. There was no police escort, no formalities. We were a small group walking behind Yellow Pocahontas, but significant enough to stop a line of cars. But one car would not stop. No, that one car sped up. The Flag Boy stopped firm in his path, his strong, feathered arms holding his flag across his body, looking squarely at the car which only increased its speed.

But this was New Orleans on a St. Joseph’s Saturday Night and we were not the only ones walking the streets. The car still approaching, a young man, a drink—not his first—in hand, ran into the road to join forces with the Flag Boy, holding out his hand for the car to stop. He knelt on Claiborne, imploring the car to slow down. And finally, out of the darkness, a man on a bicycle riding fast. A man with two fellow wanderers dressed in a skeleton body suit, complete with a homemade paper-mâchéd skull mask that covered him down to his shoulders. Like the hero of a fairytale, he arrived in the intersection to aid the Flag Boy and the drunken man. They formed a blockade only possible on a warm New Orleans night in March, on a moonlit St. Joseph’s night, in the Seventh Ward. As the skeleton man slammed his bicycle to a stop in the middle of Claiborne alongside his own newly formed ramshackle tribe, he held above his head an old and tired speaker out of which echoed and roared the sound of police sirens. And there they stood, the skeleton with a siren on a bicycle, a drunken kid on his knees, still holding his plastic cup, and a Flag Boy dressed in a suit of royal blue, allowing their entourage to pass across Claiborne, under the interstate.

I left them at that crossing and headed home.

Margaret Sowell is a writer based in the Bay Area.