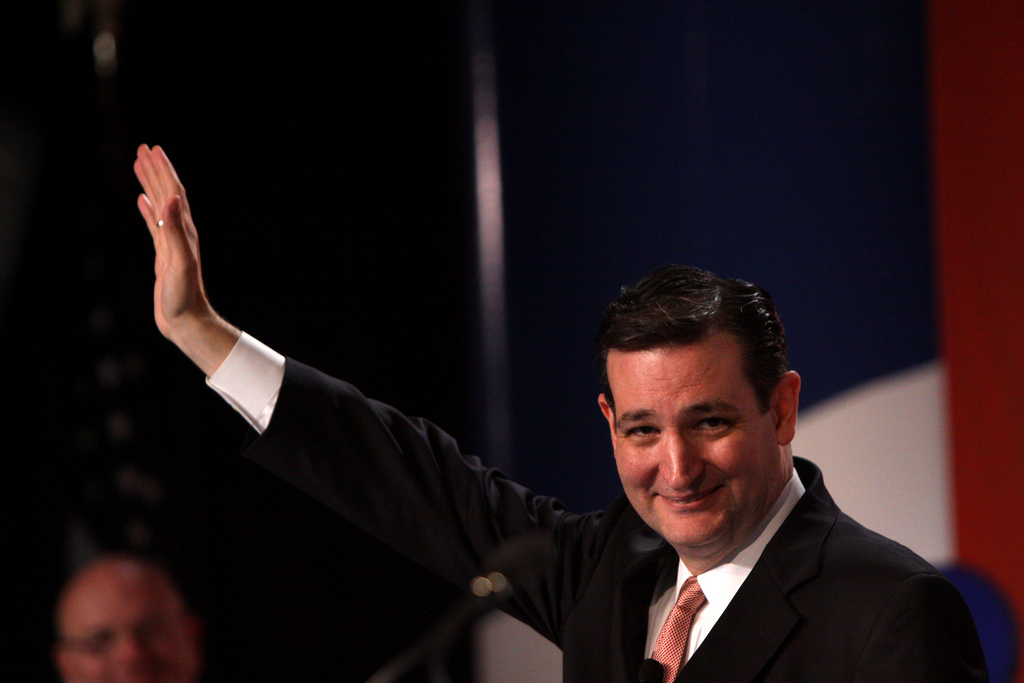

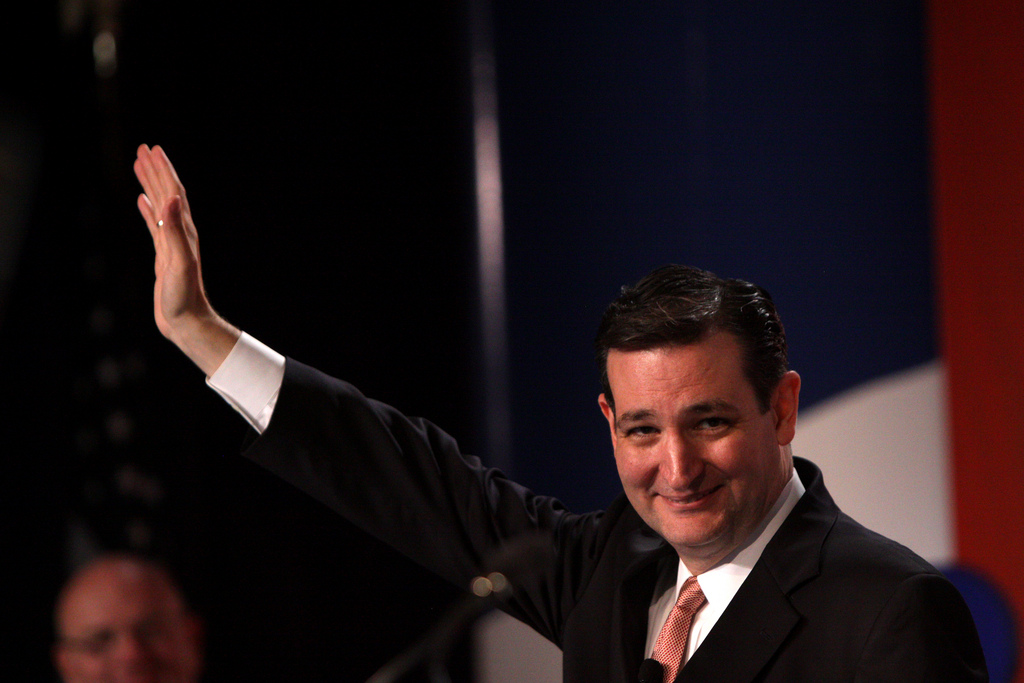

Image from Flickr user Gage Skidmore.

Ted Cruz and I were in the class of 1992 at Princeton, and we met in the dining hall our first semester in college. I was eating with a group of our freshmen classmates; we were all looking for the person we could talk about later, and trying not to be that person. Ted asked me, in a voice that made his question the business of the whole table, “Where did you go to high school?” He was like the character Farinata in Inferno 10 who rises up suddenly from his coffin and interrogates Dante: “Who were your ancestors?” Ted’s tone implied my everlasting soul was at stake. I told him where—a private school near Philadelphia. “So you had to pay to get here,” he said, leaning his face down toward mine.

I like competition. I had been a pitcher in high school and was recruited to play baseball at Princeton, and I also made the soccer team as a walk-on in the fall. I was at that moment technically a two-sport Division I college athlete. Not exactly Neon Deion, but not Napoleon Dynamite either. I realized that Ted was challenging me to a debate, but two things immediately struck me. First, his line felt canned, as if he had been prepping in his room before lunch. But, more important, Ted freaked me out. He didn’t get the social dynamic at the table, and so he was announcing his inability to make friends, not his brilliance. Although I thought I might have something to say about private and public high schools, I didn’t respond. Ted used his posture to designate a little arena over the trays and glasses between us, and then tacitly declared victory by relaxing away from me when I let the moment pass.

Ted was off-putting, but not repellent.

It is tricky to write about the past without projecting. At the time, Ted was off-putting, but not repellent. Lots of people did socially awkward things the first semester in college, like asking strangers what their SAT scores were. But the Ted Cruz I met in college is consistent with the Texas Senator and Republican candidate for president. He is antisocial: his colleagues in Congress can’t stand him. When Speaker John Boehner was asked about Cruz, he allegedly gave the questioner a wry smile and the finger. Cruz is violent: he promises to “carpet bomb” perceived enemies so aggressively that we will be able to see whether “sand can glow in the dark.” A recent New York Times piece describes his “fervor” for the death penalty. Ted Cruz fits the OED definition of a sociopath: he shows “antisocial, violent, or selfish behavior.” He also fits the much more thorough definition of sociopath from Urban Dictionary:

Common Sociopath: simple lack of conscious (sic).

Alienated Sociopath: an inability to love or recieve (sic) love.

Aggressive Sociopath: a consistent saddistic (sic) streak.

I love Urban Dictionary. If you ever want to put off writing your dissertation for a decade or so, just start your day by going to Urban Dictionary. I think what they mean for common sociopath is not “simple lack of conscious” but “conscience.” And under aggressive sociopath, I admire the poetic combination of sibilants and hard stops in the phrase “consistent sad[d]istic streak.”

A journalist called me a few weeks ago to ask if I knew Ted Cruz at Princeton. She was working on a story that floored me—although, unfortunately, I couldn’t corroborate the “absurd sexual rumor” she was looking into. (And I would so like to repeat it here, because it is a doozy.) On the phone I just sputtered, “You can’t even imagine! So creepy… I mean, no one else…” I ended up sending her my college yearbook in the hope that it might give her some leads, but before I did I sat on the couch and, for the first time in two decades, flipped through the black and white pages of the 1992 Nassau Herald.

I had another classmate at Princeton named Ted. We played intramural softball together and he shared the nickname Teddy Ballgame with the great Red Sox hitter Ted Williams. Teddy and I broke the stress of studying during our senior year by lighting sparklers on the little terrace of his quad in Spelman Hall at midnight. He majored in anthropology, and printed the final copy of his senior essay on delicate rice paper to demonstrate the “evanescence of all thought.” Teddy went on to a PhD program in the history of science at MIT; he left after a few years, got married, and started an internet company. Now he is studying neuroscience at Columbia University, and we are part of an artist collective in New York.

After college, Teddy and I and another friend of ours, Aaron, kept in touch by writing haiku to one another. One round, the theme was animals. I offered:

Kittens and chipmunks

despair! For you cannot flee

the hound’s cold, black nose.

In graduate school I spent most of the daylight hours walking my Labrador Retriever through the woods in Connecticut. Aaron was in a long distance relationship at that time; he wrote:

An egret stalks fish.

Do you lance your doubts like this?

Come—my pool is full.

Aaron and I were living right on the Long Island Sound, and he was teaching a course on Charles Darwin. Teddy was up in Boston. He replied:

I am my own vet:

sleep to jog, pills to tuna

rights sans rites of spring

I liked the way Teddy followed the theme by making himself an animal trying to care for itself. I guess he felt he was so involved in his work at MIT that although he still had some basic “rights,” like food and shelter, he wasn’t entitled to the “rites” of spring, like watching the sculls on the Charles River or going to Fenway Park.

It doesn’t matter what you do, as long as you emanate love.

One night Aaron was in town giving a reading from his book, Telling Our Way to the Sea, and afterwards the three of us went to a little restaurant on Dean St. in Brooklyn to catch up. Ted had just left his Internet startup, and I was beginning to work on an educational non-profit organization. We sat in a dark corner and had trofie with fava beans and chevre, and Vernaccia. Aaron and Ted planned to collaborate on a future project.

Toward the end of the night, as we got ready to go, Teddy said, “Well, it doesn’t matter what you do, as long as you emanate love.” He said it as a summary, but also as an aside—as if it were a cliché. Two things immediately struck me: first, the idea that emanating love is what we were supposed to be doing, and, second, that Teddy considered it a foregone conclusion that we would agree. I’m not sure how one would make that point in a debate, or even how to define its terms. But I thought, happily, You’re right, Teddy. It doesn’t matter what you do, as long as you emanate love.