A year ago, I met a friend who had just arrived from war-torn Yemen at a cafe near downtown Beirut. It was at the kind of spot where beards meant hipsters and not wannabe jihadis, where Arabic chatter was peppered with English phrases and the lemonade came with a rosemary sprig.

As a politically active journalist, my friend had every reason to leave Yemen: ruling authorities were silencing smart, moderate voices one way or another and he could have been next. “So what are you going to do now?” I asked.

“I don’t know,” he said.

It hit me that he is a refugee. The word came so loaded and the label so definitive. I balked at the thought of it, wanted to push away the truth. He’s not a refugee. He’s my friend. But he was both. To the rest of the world he was a statistic, part of the first wave of Yemenis fleeing as their country crumbled with conflict brought from the outside and within. It was a truth about my former home — and a home that I loved dearly — that I had been loathe to admit.

Despite what he had just been through, my friend was in a positive mood, laughing and reminiscing. I wouldn’t expect anything different. The Yemenis I know are walking proof of resiliency. I came to understand this all too well when I lived in the country from 2009 to 2012 as a reporter during the political upheaval and conflict brought by Arab Spring protests. But that was not war like the current one in which Arab neighbors are dropping bombs from above, in which forces from within claw one another with a new ferocity.

What good does it do to dwell on a war faraway? I didn’t want to watch the city that I loved be bombed by a foreign force. To watch other cities that I loved, Taiz and Aden, get desecrated from within.

A Saudi Arabia-led military coalition has been trying to topple a rebel militia group that took control of Yemen’s capital, Sanaa, in 2014. While unsuccessful, it is annihilating the minimal infrastructure that Yemen had before the war and terrorizing the population. Civil war among the rebels and their domestic foes rages too, doing much of the same. While enemies are closer to a peace agreement now, there is no good guy in this war, no side to root for in hopes that they are victorious.

After leaving Yemen in the first months of 2012, as the world started to realize that the wave of anti-regime protests spreading throughout the Middle East may bring more bloodshed than our hopeful energy was ready for, I happened to cross paths with a different friend in Washington DC. He was an American who had spent a year living in what is now an embattled city in Syria teaching English.

“Have you talked to people you know there? How do you deal with all of this?” I asked him.

“Honestly,” he answered, “I just don’t think about it. I block it out that I lived there. I tried to get in touch with people at the beginning, but I didn’t hear back from them, and now I don’t want to think about it.”

That’s awful, I thought to myself. That’s intentional ignorance. I’m better than that. I’m better than him.

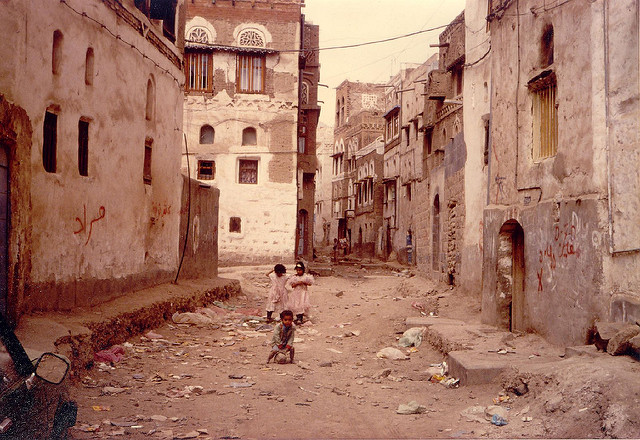

I have written before about my love for Yemen, how I enjoyed my years spent living in Sanaa. I even wrote a book largely based on that theme. At lectures I’ve given, Americans often seem surprised at this, at what life was like for a twenty-something American woman in a country that they were told is nothing but a messy knot of extremism. I’ve watched them refuse to admit it to themselves when I said that Yemenis almost always showed abundant hospitality to foreigners in their country, that I had a positive experience living in Yemen despite political violence happening around me. These Americans at the book talks thought I was the delusional one, not them. “When are people over there going to stop choosing weapons over everything else?” a man once asked me during the Q&A, his heart hardened with prejudice.

When the war in Yemen began, when Saudi jets started bombing Sanaa, part of me wanted to forget that the city being reduced to rubble had also been my home. It ruined my day to worry about how the lives of people I once lived among were in danger. Worse: it sent my already burnt out nervous system reeling. Maybe people I know are doing the killing. What good does it do to dwell on a war faraway? I didn’t want to watch the city that I loved be bombed by a foreign force. To watch other cities that I loved, Taiz and Aden, get desecrated from within. To know that it will be hard for the country to come back from this, not just because of the bombs, but also because of retaliatory fighting and killing.

When I lived in Yemen, while my situation was far easier than most Yemenis’ (I could afford the rising prices, I could leave the country whenever I chose to), I did experience some of life as an equal to my neighbors. I felt fear when the shelling started. I felt hope when peace was near. The violence was also mine. Now I don’t feel any of the things my former neighbors feel. Without living alongside Yemenis to see their strength in times of war, all I see is destruction.

I can fly to Europe and immigration doesn’t question me, and my friends can’t. I don’t have to sit in my house awake at night knowing that at anytime a bomb might hit my house, and I’ll die instantly along with my family. I don’t have to worry about when a rebel militia will release my kidnapped father. I have the luxury to turn it off. How do I not feel guilty about all that?

If I was truly selfless, I’d go back to Yemen and report. That was the person I used to be. Someone who watched too many superhero movies growing up and wanted to find the ways that I could save the day as well. But now I realize that much of my belief in my own heroism are unfounded delusions of personal grandeur. Still, none of me wants to accept the unjust truth that I can do little.

The reality of war is not reduced to a great amalgamation of suffering for which I have the choice to respond to or not. It is full of individual stories like my friend’s whose lives are at times interwoven into my own.

When I was a reporter in Yemen, at least I found purpose in telling the world about human rights abuses, about the snippets of daily life that make Yemen beautiful. This Doing Something rubbed all other guilt clean.

My futility in this current war made me want to pretend the war wasn’t there. As if it still was all about me.

When I saw my friend in the Beirut coffee shop, denial was no longer possible. This thing I tried to escape was staring at me in the face. There’s a war in Yemen and that’s why you, my friend, are right here in front of me. A wall broke, or at least shifted: the reality of war is not reduced to a great amalgamation of suffering for which I have the choice to respond to or not. It is full of individual stories like my friend’s whose lives are at times interwoven into my own.

With this realization I traveled to Djibouti to record refugees’ stories for an article in an American magazine. I sat all day, chewing qat on the floor with Yemenis, and heard that the home I once lived in, loved, taught me to be a better person, existed no more. I saw the chips in the stone. When I first moved to Yemen, I used to idealize the integrity of Yemenis and their tribal codes, but they’re people just like me, the conflict laid that bare, and I could no longer deny this war.

This trip to Djibouti also opened the well of sadness and trauma that I had tried to avoid. Afterward, when my husband, Austin, wanted to talk through his writing ideas with me, my thoughts drifted back to Yemen. When he reminded me of why I loved him, my thoughts drifted back to Yemen, and I couldn’t reconcile the two feelings — love in both cases. Love for Austin who makes me laugh, and love for a place that once made me laugh and now makes me cry. It felt impossible to hold both things at the same time. When living through a war, one clings to love because it is so needed. I’m not living through a war. I’m just watching it on television.

Why should I expect an American to care in particular about Yemeni children dying when I don’t always give the war the attention it deserves.

Then, the way I reacted to the war in Yemen became erratic, swinging from obsession to abstinence every other day. I would sit for an hour and watch footage from the war in Yemen that I had been intentionally ignoring. I tried to force myself to witness war in heavy doses, to feel the weight of what all this violence meant for Yemenis whom I used to live beside. Often, I felt nothing, emotions stunted, the mind turned protective.

Soon it became the new normal that Yemen is overrun by violence and that an agreement for peace will be difficult to come by. The country has become one of those wars that happens in the far off distance of American consciousness that a few well-read, internationally minded people keep up with here and there.

“Look at people dying in Yemen! Look at them! Children are dying!” I could yell.

But children are dying everywhere, children are dying on the path to Europe, and why should I expect an American to care in particular about Yemeni children dying when I don’t always give the war the attention it deserves.

News of a besieged hospital in Taiz floats across my laptop screen. People I know, who have shown me great kindness, are affected by this. Medical supplies there are running thin. I choose to look away.

This essay is an adapted version of the forward in the paperback edition of Laura’s reporting memoir, Don’t Be Afraid of the Bullets: An Accidental War Correspondent in Yemen (Arcade 2014).