“Please don’t tell her” was the last complete sentence I ever heard my mom say. It was less than a month after her fifty-eighth birthday and she was in her nursing home bed, riddled with lupus and cancer, fighting for consciousness. She was speaking to my stepdad, who was standing right beside me. I was the her she was speaking about.

My mom repeated this several more times, her eyes wide and intense, her back struggling to lift from the mattress, until a nurse came in to sedate her. I wanted to dismiss the entire episode as delusion or medicated nonsense, but I knew I couldn’t. Something was truly eating at her. And yet I just stood there, my face smudged with tears, not asking any questions. Addressing the pain in the room had never been our specialty.

Two years later, when I was twenty-seven, my stepdad asked me to lunch. He chose a Denny’s by his home in the suburbs of Temecula, ninety miles from where I had been living in Los Angeles. It was maybe the third time we’d had a meal together since she died. We had never been that close, and seeing each other, the grief mirrored in our faces, only made our distance more awkward.

In our bright-orange booth, we made small talk, picked apart our chicken sandwiches. There was both an urgency and stillness in the air, an unspoken sense that this would probably be the last time we’d ever be in the same room. That’s when he announced he had to get something off his chest. He raised his head to the ceiling. “Forgive me,” he said to what can only assume was my mom in dirty-vent heavens above. His eyes returned to mine. “You have a brother.”

I dropped my french fry mid-dip. My first thought was: How exciting! There’s another piece of my mom out there! Then I pummeled him with questions. How did this happen? Did she ever meet him? Does he know about me? He explained that she had given up a son for adoption when she was in college. It was a long, long time ago. A different time. His name is Tom and he probably lives in the South, where my mom grew up, but that’s all he could tell me. He didn’t want to further betray my mom’s promise that he’d keep quiet.

He motioned to the waitress for the bill. But there was one more thing I had to know: “Why in the world was she so afraid to share this with me?”

His face relaxed into a sigh. “She didn’t want you to be ashamed of her,” he said.

I’ve spent the last eleven years since that day in Denny’s wrestling with the idea of shame. At first, I dismissed my stepdad’s explanation as trite and cliché. I was befuddled that a pregnancy from more than thirty-five years ago had consumed my mom during her last moments on earth. I didn’t get why my mom, who had raised me in the diverse, accepting breeziness of Hawaii, during the era of “Like a Virgin” and Motley Crue’s “Girls, Girls, Girls,” thought her liberal daughter with a history of sad-sack relationships would judge her for—for what, exactly? For having sex in college? It was easier for me to believe that my mom, who’d always held her emotions close, was using shame as an excuse to hide herself from me yet again.

Then, during the last presidential election, it struck me how spoiled and ignorant my perspective had been. Shame is indeed a very real, very powerful and very prominently used political tool in places I am lucky to have never lived. My mother was born in 1944 in Shreveport, Louisiana, and nearly fifty years after she gave up a child for adoption, forty-two years after Roe v. Wade, Louisiana essentially remains the worst state to live in if you’re a woman: There is only one ob-gyn for every 13,000 women; it has one of the highest maternity mortality rates in the country; and abortion isn’t legal without a counseling session and an ultrasound. Even if you aren’t interested in getting an abortion, these laws demonstrate the attitude that, unlike men, women aren’t allowed to have sexual desires, that their bodies are not worthy of care or protection. They are instead vessels for procreation, most admired for their chastity and primed for deference.

Unfortunately, these far-right, highly religious ideals don’t just affect Louisiana or the South, but, as the Supreme Court ‘s Hobby Lobby decision indicated last year, the entire country, as corporations no longer have to pay insurance coverage for birth control. The attack on a woman’s right to make choices over her person isn’t just confined to election years, however; under the guise of upholding moral codes, shame has long been a manipulation tactic to keep women in subordinate, subservient roles by stripping them of their confidence and self-worth.

My mother would go on to earn her English degree, teach some of the most underprivileged kids in the country, rebuild a life for herself in a foreign place, buy her own first home, raise a “legitimate” daughter and coordinate the shit out of many outfits—and her family basically remembers her as a shameful stereotype: “loose.”

I realized then that my mother was not only raised in a culture steeped in shame, but in a culture where shame was consistently reinforced and ingested. When I recalled how she respond to what she saw as failure and disappointment—her divorce from my dad, her failing health—it suddenly seemed clear that shame had become the default reaction for my mother, a trained reflex to hide her imperfections and tamp down her sorrow.

My mother wasn’t the kind of woman who fucked up. When she found out she was pregnant with her first child, she was months away from being the first woman in her family to graduate from college. She was a near-straight-A student in her senior year at Louisiana State University, planning to go on to graduate school. But she was also, “you know, a party girl,” according to my church-going aunt who married her high school sweetheart and still lives in a quaint Louisiana town. “Who knows who the father could be?” she would later say in the same conversation, in the same judgey tone, when I asked about my long-lost brother. In the decades after my mother gave up Tom, she would go on to earn her English degree, teach some of the most underprivileged kids in the country, rebuild a life for herself in a foreign place, buy her own first home, raise a “legitimate” daughter and coordinate the shit out of many outfits—and her family basically remembers her as a shameful stereotype: “loose.”

These maternity homes were not just motivated by Christian values, but by business, as the demand for adoptable babies was also growing.

When my mom told her parents she was pregnant, they pulled her out of school during her final semester and put her in a maternity home, one of more than 200 across the country during the 1950s and ’60s, often run by religious organizations for “fallen women” to hide their pregnancies while being coerced into surrendering their children. These homes, however, were not just motivated by Christian values, but by business, as the demand for adoptable babies was also growing.

Between World War II and Roe v. Wade, more than 1.5 million women gave up children for adoption. In The Girls Who Went Away, a collection of first-person accounts of women who surrendered their kids, Ann Fessler makes clear that adoption wasn’t a personal choice, but a societal demand. When my stepdad first told me about Tom, I believed my mom gave him up because wasn’t ready to take care of a child—she was just about to start her career! —but that was my own twenty-first-century bias and privilege at work. In 1966, the country was six years away from legalizing the pill and seven years away from legalizing abortion. I’ll never know what she wanted or felt about whether or not to keep her baby—it simply wasn’t up to her. Not only were unmarried pregnant women condemned by their entire community, but without any kind of support—no partner around, no family willing to watch the child, no employers giving you the time of day—it was impossible to raise a child, known to everyone else as “bastard,” alone.

Instead, my mom, already saddled by the shame of her predicament, obeyed her disappointed parents, who dropped her off at a maternity home in Jackson, Mississippi, a state away from any gossip that could run through family social circles. There, in a sixteen-bed facility, set back on a rural stretch of road, she was issued a fake name at the door to “protect her identity.” She was confined to the grounds—with the exception of the occasional group outing when everyone dressed in disguise––and spent her days engaging in ladylike activities, like washing dishes, typing and sewing. Her mail was likely read by facilitators and her family rarely came to see her. She was ultimately alone in a strange place full of women who also felt alone, waiting out their sentences and watching their bellies grow.

In the testimonies I’ve read by women like my mother, maternity homes didn’t just make birth mothers feel faceless and disregarded, they also left these women in a state of suspense and fear. Many weren’t educated on pregnancy, labor or what they would feel once they surrendered their baby. They didn’t understand what was happening when their water broke, or why, when given an epidural shot, they felt paralyzed from the lower back down. One received so many enemas during labor, she thought she had given birth through her anus. Another, before discharge, was given her child to hold and nurse for four days before being taken away and put up for adoption, leaving the birth mother heartbroken and overwhelmed with a loss she could never speak of.

But of all the horrifying, gut-wrenching details these hundred-plus women told Fessler, the most profound was this: Every single one of them said that surrendering a newborn was the most significant, defining event of her entire life—this was regardless if she would go on to get married, have more children or run an enterprise. Like my mother, the majority of these women would eventually get married and have other kids, but also like my mom, many would never tell their husbands about the children they gave up. My dad, a former hippie-rebel who gave no shits about rules or conventions and to whom she was married for 15 years, had no idea about Tom’s existence until I told him. I asked my dad if it would have changed his opinion of her if he had known. He raised his eyebrow at me as if to say “puhlease.”

But my mother must not have believed this. Back then, women who had children out of wedlock were seen as used merchandise. They were told by parents, nurses and social workers that if they did “what was right” and put the baby up for adoption, they would move on. They would forget. However, this proved impossible. Many said it would affect their confidence, their ability to trust and be intimate. Their loss was never validated; they were never given the chance to grieve—their silence ensured that.

If you were running from your family’s disappointment, paradise wasn’t a bad place to bury a secret and begin anew.

I’ll never know exactly what my mother went through because she was one of these women who was told to keep quiet. As a teenager, I asked her why she had moved all the way to Hawaii in her twenties. She told me, “To get as far away from the South as possible.” I thought my mom—socially and politically liberal and an advocate for all aspects of equality—was referring to escaping the bigotry and intolerance where she was raised, but I didn’t realize how personal that bigotry and intolerance was: My brother was born in July, and that fall she was teaching high school English on the coast of the Big Island. If you were running from your family’s disappointment, paradise wasn’t a bad place to bury a secret and begin anew.

According to renowned shame researcher Brené Brown, “Women often experience shame when they are entangled in a web of layered, conflicting and competing social-community expectations,” leaving them feeling “trapped, powerless and isolated.” What keeps shame thriving is secrecy, silence and judgment. “The less you talk about shame, the more you got it,” Brown said.

My mom made great strides to hide her pain from me growing up. When my parents separated, when I was nine, my mother spent more and more time in her bedroom. One afternoon, however, I remember her sitting on our living-room sofa, grading papers. I was standing a half-floor above, in the dining room, looking down at her in her petite, curly-topped frame. She didn’t know I was there, but I saw her pull tissues from the couch crevices and wipe her eyes. After she was done, she hurriedly stuffed the used tissues back under her. She repeated this same routine again and again. The tears wouldn’t stop, no matter how much she dabbed them away. It was the first time I’d ever seen her fall apart and yet she was doing so in secret, hiding the evidence.

My instinct was to cuddle next to her, to make her sadness stop, but I also knew I wasn’t supposed to see her this way. “You wanna watch TV?” I called out to her. She looked at me startled, then stern. “Later,” she said. “Why don’t you go make yourself a sandwich?” I told her I already did. I stood there for a moment, hoping she’d change her mind and invite me over, but her gaze didn’t let up. I turned around and walked back to my room. I didn’t want to push her away further.

Brown says the one thing that keeps a person from connecting to other people is the fear that she does not deserve connection. “Shame depends on me buying into the belief that I’m alone,” she said. The ones who live without shame, Brown says, embrace imperfection. Even in the midst of her après-divorce depression, my mom still dressed impeccably for her audience in the classroom, and when she was bedridden with cancer and lupus a dozen years later, she continued to curl her hair every morning, at least in the front, even though she could barely lift her head to look in the mirror. Laid out flat, day after day, my mom still kept her dirty tissues tucked under her pillow.

When I finally got in touch with my half-brother Tom, I was surprised to learn he had met my mother. At the age of 21, he was able to legally obtain information about his birth mom from the adoption agency and had tracked her down. He asked if they could talk in person, and she agreed to fly down to the South later that year. I found it very curious that she would hold onto this secret for so long, only to confront it, and then go back to hiding it again. It was also peculiar as to why my stepdad was one of the few privy to Tom’s existence: Since they were newly married when Tom came forward, she may have been feeling more open, or maybe she thought he’d be a more accepting partner in a more accepting time—or he could have simply been in the room when she got the call.

Regardless, that summer, Tom and his adoptive mother drove up from his school in Mississippi to meet my mom and stepdad at a hotel restaurant in Louisiana. Tom—today a successful business man with a wife and two kids and who I’ve grown close to—told me their meeting was as awkward as one might expect, and even more so since my stepdad seemed to be learning things about his new bride right along with her long-lost child. Tom said what he remembers most about that evening was my mother’s wit—he could tell they had the same sense of humor. But he hemmed and hawed when I asked what else he could tell me.

“It’s okay, be honest,” I told him. “Was she ecstatic to meet you?” I had read that many women were flush with excitement and emotion when they met their relinquished child—as nerve-racking as it was to finally come face-to-face, it opened a wound that had the possibility of healing. However, knowing how the rest of her life played out, I had a feeling that this was not the case with my mother.

Tom paused. “Actually, she was a little withdrawn,” he said.

For the next ten years, my mom and Tom would occasionally write and talk on the phone until communication from my mother dropped off. The last time he heard her voice was when he called to tell her that he’d be with his wife and young daughter in Kauai for vacation. He offered to fly her out there, a 40-minute plane ride to meet her granddaughter, who, now at eighteen, looks more like my mom than I do. But by then, my mom was unwell and withdrawn. When my brother arrived in Kauai, he called again, hoping she would change her mind. But she never answered.

Back in 2004, researchers at UCLA discovered that shame had an effect on the immune system, particularly pro-inflammatory cytokine activity, or inflammation. Cytokines are a broad group of proteins that regulate the maturation, growth and responsiveness of certain cell populations, especially in the immune system; when inflamed, they tend to make disease worse. In the study, a group of healthy subjects was asked to write about a trauma in which they blamed themselves, and those who reported the greatest instances of shame also had the highest increase of pro-inflammatory cytokine activity.

Pro-inflammatory cytokine activity is often affiliated with arthritis and high blood pressure. By the time my mom was forty, she had both. By fifty, she was diagnosed with the autoimmune-deficiency disease lupus, which flared up greatly in the last eight years of her life and made her less and less mobile. She also took several hard falls, which led to back and hip surgeries and which she jokingly attributed to her clumsiness, a.k.a. the mind removed from what the body is presently doing. At fifty-six, she was diagnosed with stage-three breast cancer—she had missed the previous year’s mammogram because she had been in the hospital for lupus. A year before that, she had already resigned to spending most of her days in bed.

In The Girls Who Went Away, one woman says she met birth mothers in her support group who went on to die from cancers in their fifties. “I mean, trauma is not a mystery,” she said. “It really attaches to yourself in a way that’s hard to undo.” Brown, the researcher, is more straightforward: “I think shame is lethal. I think shame is deadly and we are swimming in it, deep.”

When conservatives dismiss the idea of slut shaming, I think of my mother. Shame was not a moment or a phase; shame held her tight, right up until the end.

While it took me awhile to understand all the emotional and behavioral repercussions of shame, I had been thinking about how it physically affected my mother ever since the drive back from Denny’s. I imagined how swallowing such a massive secret and locking it in the pit of her gut for thirty-five years must’ve weighed on my mother’s body. I pictured knots forming in her stomach, toxins accumulating, organs stressed. Every cumulative time my mother suffered silently, I pictured another knot, another toxin, another stress building on top of the last.

When conservatives dismiss the idea of slut shaming, I think of my mother. Shame was not a moment or a phase; shame held her tight, right up until the end. Shame is your subconscious breaking through all the boundaries of your body to scream, “Please don’t tell her.”

If you asked me at age twenty-five, when my mom died, if I thought I was a shameful person, I’d look at you like you said I was a circus clown. Regret is for suckers, I’d say. I wear whatever I want, date whoever I want, say whatever I want. But being an unapologetic, outspoken self-righteous young person was not the same as being open and honest with myself. I was deeply, direly ashamed of my own vulnerability, just like my mom was.

After college, I moved away from my mother, who was already pretty ill with lupus, to Los Angeles. I told myself I was leaving to start a new life, to begin my career, to see what excitement awaited me outside of an island. But I also knew this was my only window to get out, or else I’d be forced to sit around and watch my mother deteriorate into a shell of herself.

About three months after moving to L.A., my mom called to tell me she had breast cancer. It’s not a big deal, she said, “Don’t worry about me.” A year later, she called to say she and my stepdad were moving to Temecula, about an hour and half away from where I was living. She never told me she was coming to California because she missed me, because she was dying, because she was scared and they needed help. She had long ago learned not to express her wants and fears; I’m not so sure she could even recognize them anymore. And that was okay with me, because it gave me an excuse not to express the incredible, frightful void that I felt too. Instead, I went for the easy emotions: frustration, anger. I saw my mom and stepdad’s arrival as an inconvenience, an unwanted reminder that soon she’d truly be gone.

Once they settled in Temecula, I begrudgingly visited my mom at their townhome once or twice a week. In college, I often did the same, driving out to their house in the suburbs of Oahu to lie in bed with her for hours, watching soap operas and Friends reruns. Back then, we could laugh about the absurdity of plot points and discuss the weirdoes at my restaurant job.

In her California home, however, my mom began keeping the windows closed and the air-conditioning on high in her bedroom, trapping us in the scent of brand-new in-denial furniture and a woman who never left her bed. Sometimes I’d show up hungover, enabling me to lie numbly next to her, thinking as little as possible, until the sun went down. On my back watching the TV, I didn’t have to see that she was locked in a brace to protect her spine, or that her eyeliner wasn’t applied as straight as it once was. We barely spoke, maybe only a sentence or two every hour about what we were reading in the celeb-gossip magazines she got in the mail and would save for my visits. We had no idea how to talk about the pain that was building inside of us.

When I wasn’t around her, I was also detached—possibly even in the same ways my mother was when she was in her twenties, looking for comfort in bar buddies and consumed with how she appeared. I drank too much, hoping to feel like all my “normal,” carefree friends. I continued to welcome hangovers to quell the anxiety that rose from my stomach to my jittery brain like a shaken soda bottle. I overate to fill the cavity my mother had left in my heart and I over-exercised and took laxatives to release myself from the guilt of trying to fill that hole with something that wasn’t her. And like my mom, I did all these things so I wouldn’t have to acknowledge how alone I felt. I didn’t want to reach out to my dad, my boyfriend or my friends because I was afraid they’d learn I wasn’t as tough as I thought I was. I was ashamed to be broken.

A week before my mom said her last words, I came to her nursing home bed, frazzled. I told her I felt like I was going crazy. I told her, sort of, that I didn’t know how to cope. “I don’t have siblings,” I said. “I don’t have a husband to lean on like you did when your parents were, you know, ill. I don’t know how I’m supposed to deal with this.” She looked at me, as tears streamed down my chin, like she wanted to empathize but couldn’t. “How long do you think you have?” I asked. She turned toward the window. The midday Southern California sun picked up the flecks of gray in her eyes, which were otherwise dulled, medicated. “A year,” she said in a sweet, far-away voice. “Maybe two.” I had waited too long to reach out to her. She died three weeks later.

My unraveling that day was just the very beginning of a long, reluctant release of emotions I hadn’t been sure I had the right to feel.

Brown says shame cannot survive empathy; it cannot survive being spoken. I am grateful to have uncovered shame’s motives and machinations. Through time and people who gave me the space to fall apart, I began to accept even my darkest shades of gray. To better understand how it’s shoved down the throats of undeserving women like my mother for political, professional and romantic gain. To have dug through its ugliness to hurt for my mom in ways she wouldn’t allow herself to hurt. Breaking free of shame’s silence was to stop letting it have any power over who I thought I was supposed to be. Or who my mom was supposed to be, either.

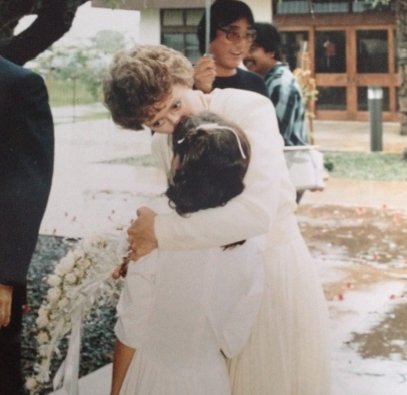

I recently went through old photos of my mom and I, trying to remember moments that were more nuanced, less staged. There were many pictures where I was at my mother’s hip; her slender arm secured my bony frame at her side, our lapels ironed, our smiles bright. But then, I found an image that was much more striking in a complex, imperfect way. It was taken on her wedding day to my stepdad, when I was ten. My mom is in a long-sleeve off-white dress, facing the camera, an arm around my back, bending down to kiss my forehead. Her eyes are fixated on the distance, entangled somewhere with her mind, and it is there that I can see she is withholding. But I can also see that she is pulling me in close. She is loving me the way she can.