Photograph by Jane Marchant

It is winter here and there are no leaves in sight. I am standing in front of what was once 684 East 39th Street, once part of Chicago’s Ida B. Wells housing projects. Gray dust swirls to the sides of the roads; it also covers cars. Gray light shines through gray clouds and gray glass litters Bronzeville’s streets, in the South Side. The Chicago Housing Authority demolished my Grandma Barbara’s first home. In place of the two-bedroom apartment that housed my Grandma Barbara, her two siblings, and their mother – and generations after them, as the city’s public housing projects shifted from idyllic dream to dangerous nightmare – are three-story apartment buildings for rent or sale. Demolition of the Ida B. Wells Homes began in 2002 and construction for the Oakwood Shores replacement development is nearly complete. A manufactured park cuts the new housing development in two, Lake Michigan breaks against the shore barely a mile east, and skyscrapers rise in the distance. Barely five months ago, I did not know my Grandma Barbara grew up in Chicago’s first housing projects segregated for black residents. She kept many things hidden from me, and the outside world. Among Grandma Barbara’s secrets was that her mother was black.

I love my Grandma Barbara. I loved her as I grew up in a predominantly-white neighborhood; I loved her when I wasn’t allowed to play with her hair, when she ate peanuts and jelly beans at our dining-room table, and when I understood she and my mother were somehow different from the white mothers around us, but I did not understand why. I loved Grandma Barbara in her hospital bed, as she told the nurses she was from Spain, as she lay dying. I love her as she rests in a jar on my aunt’s mantelpiece. But Grandma Barbara told her children and grandchildren lies about who we are.

I find myself, repeatedly, asking, Why? Slavery’s dangers do not exist anymore. The segregation of Grandma Barbara’s youth does not legally exist anymore. When she was on her deathbed in 2007, she was no longer called a mulatto, my mother no longer called a quadroon; I am not called an octoroon, my children will not be named mustifees and my grandchildren will not be mustifinos. We are not in the French Southern States of the 1800s and my great-grandchildren will never be called quarterons, and their children sang-meles. Our one drop will no longer enslave us all. So what was Grandma Barbara hiding from?

My grandmother’s lies have rippled across our family tree. Her lies cut my mother and her siblings off from their family. My mother said to me, “The lies have hurt us for too long.” And so I have set out to find the truth.

I understand that I am only at the beginning of my journey, as I ask relatives about our family history and search through archives to confirm their tales. I am first led to the towns of Louisville, Kentucky, and Jeffersonville, Indiana, which face each other across the Ohio River. Kentucky was a slave state. Indiana was not. Swimming or boating across the river’s murky water resulted in freedom only when touching Indiana’s shore. The two communities segregated themselves into white and black. My ancestors moved their church board by board across the Ohio River and into Indiana, where my Grandma Barbara’s mother, Jean Allen, was raised.

Government records list my great-grandmother, Jean, as “Negro.” Sometimes she is recorded as Jane Allen; sometimes her birth date is 1906, sometimes 1903. She was beautiful, with a graceful neck and piercing eyes. One relative said that when Jean was sixteen-years-old, she got into trouble with her mother for riding a motorcycle. After finishing four years of high school, she spent a semester at mortuary school. A corpse sat up on the table, due to a buildup of gas, and Jean dropped out to move to Chicago.

Government records list my great-grandmother, Jean, as “Negro.” Sometimes she is recorded as Jane Allen; sometimes her birth date is 1906, sometimes 1903. She was beautiful, with a graceful neck and piercing eyes.

Somewhere between 1925 and 1929, friends introduced Jean to John Maurice Galvin; he was born in 1902, went by “Maurice,” and was one of thirteen Irish-Catholic siblings. In his early twenties, he lived in a small town in North Dakota, where he and a friend stole a steer and tried to sell it to a local butcher. The butcher knew immediately whom the steer belonged to, and a warrant was put out for Maurice’s arrest. He skipped town, at some point joined a rodeo, and ended up in Chicago. Perhaps Jean was impressed by his story about the steer, or by his sense of adventure. Perhaps it was true love.

But I have learned that since Jean Baptiste Point du Sable – a black man – was the first settler on the Chicago River in 1779; since the War of 1812’s battle at Fort Dearborn between US Troops and Potawatomi Native Americans; since Abraham Lincoln was a candidate during Chicago’s Republican National Convention of 1860 and someone whispered to the chairman of the Ohio delegation, “Swing your votes to Lincoln, and your boy can have anything he wants;” since Reconstruction; since the largely-forgotten fire of 1874 that burned downtown, forcing displaced black residents to the less-populated South Side; since the Black Codes and the establishment of Jim Crow; and since the Great Migration began and ended, Chicago has been one of the most segregated cities in America. City officials drew lines through neighborhoods and placed people on either side. Jean Allen and Maurice Galvin were segregated into different streets of black and white. There was no room for gray.

And while anti-miscegenation laws in Illinois were overturned in 1874, it was illegal in Indiana for a black person to marry a white person at the time of Jean and Maurice’s relationship. Until 1965, the Indiana Constitution provided that “when one of the parties is a white person and the other possessed of one-eighth or more of Negro blood,” the marriage is “absolutely void without any legal proceedings.” Indiana’s Constitution went on to legislate that “every person who shall knowingly marry in violation of the provisions of this section shall, on conviction, be fined not less than one hundred dollars nor more than one thousand dollars, and imprisoned in a state prison not less than one year nor more than ten years.” The same monetary fines were applicable to those counseling or assisting in the interracial marriage.

Yet somewhere between 1929 and 1930, Jean and Maurice went on a double-date to Crown Point, Indiana. The town’s justice of the peace advertised in Chicago that couples could marry twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week, at Crown Point’s marriage mill. From 1915 to 1940, approximately 175,000 couples married at its Lake County Courthouse. And on Jean and Maurice’s double-date in Crown Point, someone suggested they get married.

This can’t be the full story: I wonder how, with anti-miscegenation laws in place, Jean and Maurice could have been married. Some family members say that Maurice asked his friend to pretend to be justice of the peace for the ceremony, or that the license was falsified, or Maurice and his friends thought it all a fun joke. My family is full of mysteries and I don’t know how much Jean knew about the law or men, but I know that when Jean declared her marriage vows, she gained an ephemeral husband and lost her family – they disowned her because of her relationship to a white man. And on October 16th, 1930, Jean gave birth to her first daughter: Norma Galvin.

Family lore says Maurice took a different wife, instead of Jean. This story has been told to make ourselves feel better about Maurice’s actions, to make us feel like he loved Jean and met her after he had already had married another woman, the wrong woman. But I found records. The US Census of 1930 lists John Maurice Galvin as a yard clerk for the railroad, while living with his parents at 6937 Calumet Avenue. He had married a woman recorded as white, named Charlotte Galvin, the year his first daughter with Jean was born, and he brought his legal wife to live with him and his family.

In the depths of the Great Depression’s absent fathers and hunger lines, on November 10th, 1931, Jean again went into labor. My grandmother was born first. A doctor used forceps to pull her twin out of the womb and Jean named her babies Barbara and Robert Galvin. Jean had no family besides her children; they were effectively homeless, living off the kindnesses of friends.

Photographer unknown

Photographer unknown

Photographer unknown

While interviewing my grandmother’s twin brother, Robert, in Chicago, he shared his first memory with me: he was in a hospital. It was all white. He was an infant and he was being dunked into a bathtub, scrubbed, and passed to another woman in white to dry him off. There was a long line of children being bathed and dried. Jean couldn’t get out of bed to care for her babies, due to heartbreak or exhaustion or both. Her children had been sent to an orphanage. Robert was too young to have a clear memory of time, and does not know how long he and his sisters lived there.

Outside the orphanage, carpenters, bricklayers, and electricians set up Chicago’s Century of Progress World’s Fair, to take place from May 27th to November 1st, 1933. Wooden boards were nailed to form the Dragon Ride. The Village of “Darkest Africa” brought Nigerian royalty and Belgian Congo pygmies from the African continent to show “Real African Life in a Real African Village.” The Infant Incubator Company arranged premature babies in rows. The “Plantation Show” portrayed happy slaves dancing bare-breasted and a concession called “African Dips” involved throwing balls at live, black men.

Two miles directly south from the fairgrounds, from 22nd to 63rd Streets, in between Wentworth and Cottage Grove Avenues, Jean regained custody of her three children. They – along with two-thirds of all black Chicagoans – were segregated, the vast majority in poverty, in what had become known as the “Black Belt.” Between 1920 and 1930, the US Census reported an increase of 124,445 black residents in Chicago. Jean was not the only mother desperate to shelter her toddlers, as she moved from cheap, temporary apartments to friends’ couches, taking in odd seamstress work.

The Depression had halted the housing industry and almost all construction: only one-hundred-and-thirty-seven new units were built in Chicago in 1933. A special census in 1934 showed the average black household, such as one that Jean and her three children had stayed in, contained 6.8 people, compared to 4.7 in the average white home. That year, the city demolished approximately seven-thousand black housing units they had deemed “sub-standard.” Many still-standing black homes lacked plumbing or entire apartment floors shared one bathroom. Men and women and children squatted in the abandoned Pythian Temple at 37th Place and State Street. On New Year’s Eve, 1935, The Chicago Tribune ran an advertisement for mascara that withstood cold-weather tears; the weather that day oscillated between eleven and twenty-five degrees Fahrenheit. There was no heating in squatted buildings such as the Pythian Temple. Unsanitary conditions led to rat attacks on sleeping children, frequently resulting in maiming or death. No one can tell me exactly where Jean’s small family slept during these times.

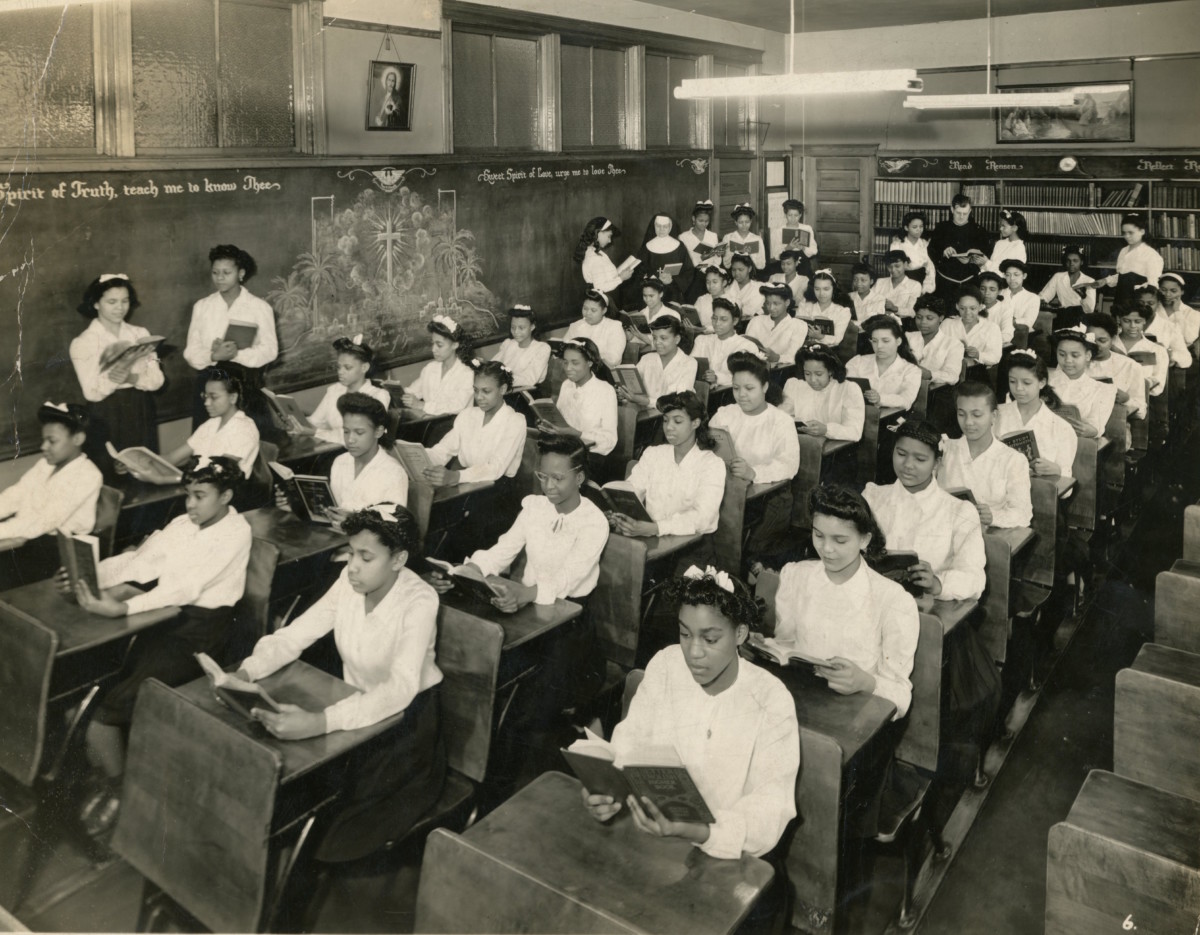

When President Franklin Delano Roosevelt won a landslide reelection in 1936, his New Deal political reforms brought forth the Chicago Housing Authority. Chicago’s first three housing projects opened in 1938, with space for 2,378 white families. In 1939, engineers, plumbers, steam fitters, and structural-steel workers broke ground on a forty-seven-acre property that would cost nearly nine million dollars and shelter 1,662 black families. The Homes were segregated in accordance to the federal “Neighborhood Composition Rule,” which required housing developments to mirror the racial composition of the neighborhood they were being built in. Named after the renowned black journalist and social reformer, the Ida B. Wells Homes were composed of two-to-four-story buildings; the community even had space for vegetable gardens. Some 17,544 applications were received, including my great-grandmother’s.

Jean miraculously received a housing assignment and she held her head high as she walked through Chicago’s South Side, her three adolescents in tow. They were tired, they were poor, and it was 1941. They had essentially been homeless for a decade when they entered 684 East 39th Street. Between Cottage Grove to the east and South Parkway (now Martin Luther King Drive) to the west, their home had its own kitchen and bathroom. Sisters Norma and Barbara shared a bedroom; their brother, Robert, had his own room; and Jean slept downstairs on the couch. Rent was thirty-six-dollars per month – if one had it. Sometimes, payment arrangements could be made, or neighbors chipped in to help. The Homes were a community and a respite for families during the Depression. Jean’s children took free dance, music, and art lessons at the Abraham Lincoln Center. Norma tapped her pillow at night, practicing her imaginary piano. Barbara dreamed of becoming a professional ballerina. Robert wanted to be a cowboy, like his heroes on the radio. An enumerator from the Sixteenth Census of the United States marked Jean, Norma, Barbara, and Robert Galvin as “Negro” in his wide logbook. The enumerator asked Jean if she worked, to which she replied she had no income. She told the enumerator she’d been married to the same husband since she was eighteen-years-old.

In their new home, Maurice visited Jean late at night, while the children slept. They awoke some mornings with black licorice under their pillows. The children were told their father had snuck into their rooms and left the candy so they would know he had visited. In our interviews, I didn’t have the heart to ask my great-uncle, Robert, when licorice became his favorite candy, or to ask him if it was really Jean leaving licorice, lying to her children about how much their father cared for them. I didn’t dare ask what Maurice left with Jean. It felt as if I was trespassing too far into my great-uncle. The new power I have claimed over our family narrative unnerves us all. I asked my mother instead; I somehow feel safer trespassing her. My mother told me she wouldn’t be surprised if Maurice left money for the family on Jean’s pillow.

During Jean, Norma, Barbara, and Robert’s first winter in the Ida B. Homes, on December 8th, 1941, President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s gritty voice echoed down 39th Street. World War II had come to America. While the Depression lifted nation-wide, life in Chicago’s South Side remained treacherous. Jean slept with an old police revolver – supposedly given by Maurice – under her pillow. One night, a hand felt along a first-floor windowsill and attempted to open their window. Jean shot one bullet and the hand disappeared, along with its owner. The children walked to and from school together, and were told to keep their mouths shut when they crossed Cottage Grove to avoid getting beaten up. Yet Jean’s children were lucky; at night, they listened to westerns on their radio, safe under blankets. Neighbors made dandelion wine from flowers growing in sidewalk patches.

After the Second World War ended, conditions still worsened outside the Ida B. Wells Homes: semi-distant black neighbors occupied cardboard basement cubicles ten-families full, with no windows or toilets. Two-Gun Pete ruthlessly policed the neighborhoods, gunning down nine men by 1945. The size of the urban rat population approached that of the human population. In the year between my Grandma Barbara’s fifteenth and sixteenth birthdays (from 1946 to 1947), over seven-hundred-and-fifty fires burned decrepit buildings and slums in Chicago’s Black Belt.

Society called my Grandma Barbara and her siblings mulattos, diminutives of the Spanish word mulo, that hybrid animal, the mule. Barbara’s skin was light enough for her to introduce herself as Spanish, Irish, or anything-but-black, if she could only leave Chicago, where people knew who she was. When Barbara was eighteen-years-old, she met a man of Mexican heritage on a public bus. She told him she dreamed of getting out of Chicago, of traveling and dancing in ballet companies around the world. I wonder where on the bus they were sitting; I wonder what race she told him she was; I wonder when she first decided to let her light skin count for something other than black. He promised to take her to California. Barbara never wanted children. He told her he was sterile.

She quickly became pregnant.

Culturally, my mother is not black. She was not raised within the black community; she was not segregated into schools like her black cousins in Chicago. Ethnically, my mother is part black, part white, and part Hispanic. My heart tightens when someone asks her ethnicity and I hear her reply: “I’m a Mutt.”

When my mother was four or five, her father left his last name and the Los Angeles apartment his family was living in. There were four small children in Barbara’s house by then. Her children grew up in rough areas of East L.A. My mother and her siblings ran barefoot along the concrete banks of the Los Angeles River, getting algae and residential discharge in between their toes. Their mother, Barbara, married twice more, raising seven children while frying slices of Spam, painting shower curtains by hand, driving buses, working at the post office and later as a deputy sheriff, and finally as an elementary school teacher’s assistant. When Barbara’s sister, Norma, visited with her husband and children, my mother’s cousins were “black because Aunt Norma had married a black man.”

Barbara’s mother, their Grandma Jeanie, was Menominee Indian. Yet my mother and her siblings were told they were Puerto Rican. My mother and her siblings were kept away from Chicago; they missed the births, family milestones, reunions, and deaths that typically bring families together; and my mother, as a child, was unaware of what she had lost. My Grandma Barbara was aware of the clear racial hierarchy that existed around her and her children – and anything was better than the blackness from where she had come.

Then, in 1971, at eighteen-years-old, my mother went to stay with her Aunt Norma in Chicago’s South Side. Aunt Norma had remained in Chicago after Barbara left, embracing her black identity. My mother said Aunt Norma “had the drive of Hercules.” She was one of the the first black students to graduate from Mundelein College in 1953, and went on to serve as principal of a South Side school, raise six boys, and become a lawyer in her late fifties. When my mother arrived on the South Side and discovered she was black, she told me she felt like a curtain was lifted and she finally fit, racially, into her family.

Yet I still watch my mother struggle with her identity. Culturally, my mother is not black. She was not raised within the black community; she was not segregated into schools like her black cousins in Chicago. Ethnically, my mother is part black, part white, and part Hispanic. My heart tightens when someone asks her ethnicity and I hear her reply: “I’m a Mutt.” She means, she’s a mixture of a lot of things, and she doesn’t want to go into detail; she thinks her ethnicity is none of their business. For me, when she defines her race this way, it feels as diminutive as mulatto – mulo – mongrel – animal.

Photographer unknown

Photographer unknown

When the time came for my mother to choose a husband, she married a white man and moved her children into a white neighborhood. My mother still had to sort through dented cans at the Grocery Outlet and my father rationed our showers for the sake of our water bills, but we were in a better place than where she had grown up. My mother wanted her children to grow up where it was safe for them to walk home from school, where they wouldn’t smoke cigarettes on street corners or fall through factory roofs or accidentally burn down buildings, as she and her siblings had done. When she looked my sister, my brother, and me, I think that my mother saw her past as her children’s future. And so she, too, hid stories from us, saying we didn’t need to know certain things.

But she was different than the other mothers; we were different than the other children. Our mother was the only mother who baked biscuits or cornbread. Our mother burned our grilled cheeses and scraped the black off with a knife. There was no denying our brother’s brown skin tone, no hiding the curly or coarse hair-texture of my mother, sister, and brother. Our house smelled like incense and none of our furniture matched and the colors were always bright, too bright, when compared to the beige interiors of white friends’ homes. And because I didn’t have any explanation, because no one talked about our race, I was ashamed of my mother, and whatever it was that made her – and us – different.

Then, when I was twelve years old, a black man knocked on our front door and said he was my mother’s brother. He was tall, six-foot-four or so, and we marked his height – Uncle Kevin – on our wall above Great Uncle Bob and Grandma Barbara. After the visit ended and the door shut, I asked my mother, “How do you have a black brother?”

“Jane, I’m black,” she said.

What? I kept questioning her. My mother told me that Grandma Barbara had given birth to Kevin in Los Angeles, but couldn’t raise him; he had to be given up for adoption. “But why was he black?” Grandma Barbara’s mother was black, but Grandma had hidden her blackness; her blackness crept out in the baby’s skin. I didn’t understand procreation and genetics and that Grandma Barbara had slept with a black man who was much darker than her and her siblings.

“Does that make us black?” I asked my mother, referring to my siblings and me.

“Yes.”

I felt limitless confusion yet also relief; I understood the something that made us different, but at the same time, I felt like I knew even less than before. I was instantly someone new. But what? I didn’t always get the same answer. My great-grandmother was black; my great-grandmother was half-black, half Native American Indian. My great-grandmother was a Black Indian, kicked off her reservation by white men; her daughter, Grandma Barbara, was white or Puerto Rican or Spanish or Irish, but never, never black. Her blackness was hidden, a secret, kept at bay by staying in the shade and using sunscreen and rubbing creams labeled sun spot remover on her face and neck and arms.

The lies passed down from my grandmother have led to multiple family members passing as white. I have now, sixteen years after discovering my grandmother’s secret, begun to question it in earnest. I have begun to read about and question the history of passing; I have begun to ask black friends about their hidden relatives, and I ask my family questions they have never felt comfortable answering. But what I am really asking is, Am I black?

In the past, within the black community, there was an ethos about passing: if you leave us to live as a white person, if you go somewhere else to make your life better, you better make sure you do something grand. Don’t go live your life the way it would have been if you hadn’t left your family, your history, your people, behind. We understand the need to pass for survival, for dreams, for an offer you couldn’t resist; we won’t call you out when we find our features hidden in your face or hands or the shade of your skin. (Even now, I am asked slowly, tentatively, “What ethnicity are you?”) And to those that do pass: if you get out, you better make something of yourself that you couldn’t as a black person. So I ask, what would Grandma Barbara’s life have been, had she stayed in Chicago, with the support of her family?

Photograph by author’s mother

By the time the Supreme Court ruled in Loving v. Virginia to legalize interracial marriage across America in 1967, my Grandma Barbara was long gone from Chicago and her white father had been dead one year. I think about the white man, Richard Loving, and his black wife, Mildred Jeter; I think about how much he must have loved her to fight the state of Virginia to be with her. I think about my great-grandmother, Jean, and about what happened on her wedding day in Crown Point, Indiana. I think about the anti-miscegenation laws that existed at one point in forty-two states. 1662: Virginia was the first to illegalize interracial marriage. 1664: Maryland. 1705: Massachusetts. 1913–1947: thirty states illegal, eighteen legal. 1948: California legalized miscegenation. As years passed, legalization crept across the country, until 1965, when Indiana legalized interracial love, and then 1966, when the only states that had not legalized interracial marriage were seventeen states in the South. I wonder what Jean and Barbara were doing on June 12th, 1967, when the Supreme Court announced its decision. I wonder if they spoke on the phone about Maurice. I want to think that maybe Grandma Barbara had it wrong about her father, that he did love her. I want to think that maybe Maurice just wasn’t strong enough for the fight; I want to think that, maybe, when he died after two years of being bed-bound, it was out of guilt. I don’t want to think that my great-grandfather never cared, that he thought so little of the black woman he bedded and the children she bore. I am part her, part black, but I am also part him.

But why should this even mean anything to me, when I could easily allow people to continue their initial assumptions that I am white? Why do I feel I have to audibly correct people with the statement, “I’m not all white”? I have only met my Great Grandma Jeanie once in my life, when I was five-years-old, and although I didn’t know then what race looked like, I knew that I loved her. She came to visit us in California and, in our backyard, I sat in her lap and ran my fingers over her dark brown arms. It was summer. Her wrists were thin but strong and she had a constellation of freckles on her forearm’s papery skin. I don’t remember asking Great Grandma Jeanie why her skin was darker than mine, but I must have, I must have noticed our different shades. Her white hair glowed like a halo around her head and she sat up as straight as our white Barbie dolls. She let my sister and I brush her hair – something her daughter, our Grandma Barbara, never allowed. She moved as if she belonged in another time.

I didn’t know that people called her black. My mother, her sisters, and their mother never talked about blackness. I wonder if I asked my mother about the darkness of Great Grandma Jeanie’s skin; I must have. Why do we, as children, not remember such vital moments of life? I didn’t see Great Grandma Jeanie’s skin as black; black was for crayons and night and the plastic on videocassette tapes. No human was black. I didn’t know what it meant to be black; I didn’t know what the word meant. I didn’t know that blackness comes in shades. I just knew Great Grandma Jeanie had fluffy white hair that she let my sister and me clip pink-plastic barrettes into, as we sat in the sun under our sweet-flowering ficus tree. I knew that whatever Great Grandma Jeanie was, I wanted to be like her. I am proud to be of the same blood of a woman like her; I am now proud to be my mother’s daughter.

I wish that I could have spoken as a woman with my great-grandmother. I wish I could have sat down on a park bench or walked on a beach with her or drank a glass of wine with her and asked her for all of her secrets, all of her truths. But I only met her one time. She died that fall, on October 7th, 1992, when I was five years old.

Photograph by author's mother

Photograph by Jane Marchant

After my Great Grandma Jeanie’s children moved out of their apartment in the Ida B. Wells Homes, she stayed a few years before moving on herself. A new family moved in. Jean remarried, this time to a black man, and became Jean A. Hector. Apartment towers were built around the Homes, and another family moved in. Jean went back to school, in her eighties, to earn her associate’s degree (although I have conflicting information on her age and type of degree). The Homes’ walls deteriorated; sink handles broke; profanity and graffiti covered the exterior. Before Jean died, she found out the father of her children was buried in the same cemetery where she had purchased a plot. Gangs with knives and guns and drugs controlled the projects. Jean asked to move her plot to the opposite side of the cemetery from where Maurice and his family were buried. Another family moved into the Homes. And by 2002, what had once been a desirable community had become a dangerous failure of the Chicago Housing Authority. Grandma Barbara’s home – her history ¬– was torn down and shiny new homes were built for a new century.

I didn’t see Great Grandma Jeanie’s skin as black; black was for crayons and night and the plastic on videocassette tapes. No human was black. I didn’t know what it meant to be black; I didn’t know what the word meant. I didn’t know that blackness comes in shades.

When I was younger, I thought Grandma Barbara had wanted the West Coast dream life. I have come to understand that she was in pain: everything that happened to my great-grandmother and her children – their homelessness, their poverty, their segregation – was decided by race. When my Grandma Barbara looked in the mirror, she saw the reason that her father didn’t love her enough to stay. I’ve thought, Grandma would have peeled off her skin if it meant he could love her. But she couldn’t, and he couldn’t. So she ran away, leaving her family and blackness behind her. And now I am back, trying desperately to regain what she erased.

On my day in the South Side, I see one white person – if I don’t count myself.