Photo courtesy of Carol Kovinick Hernandez.

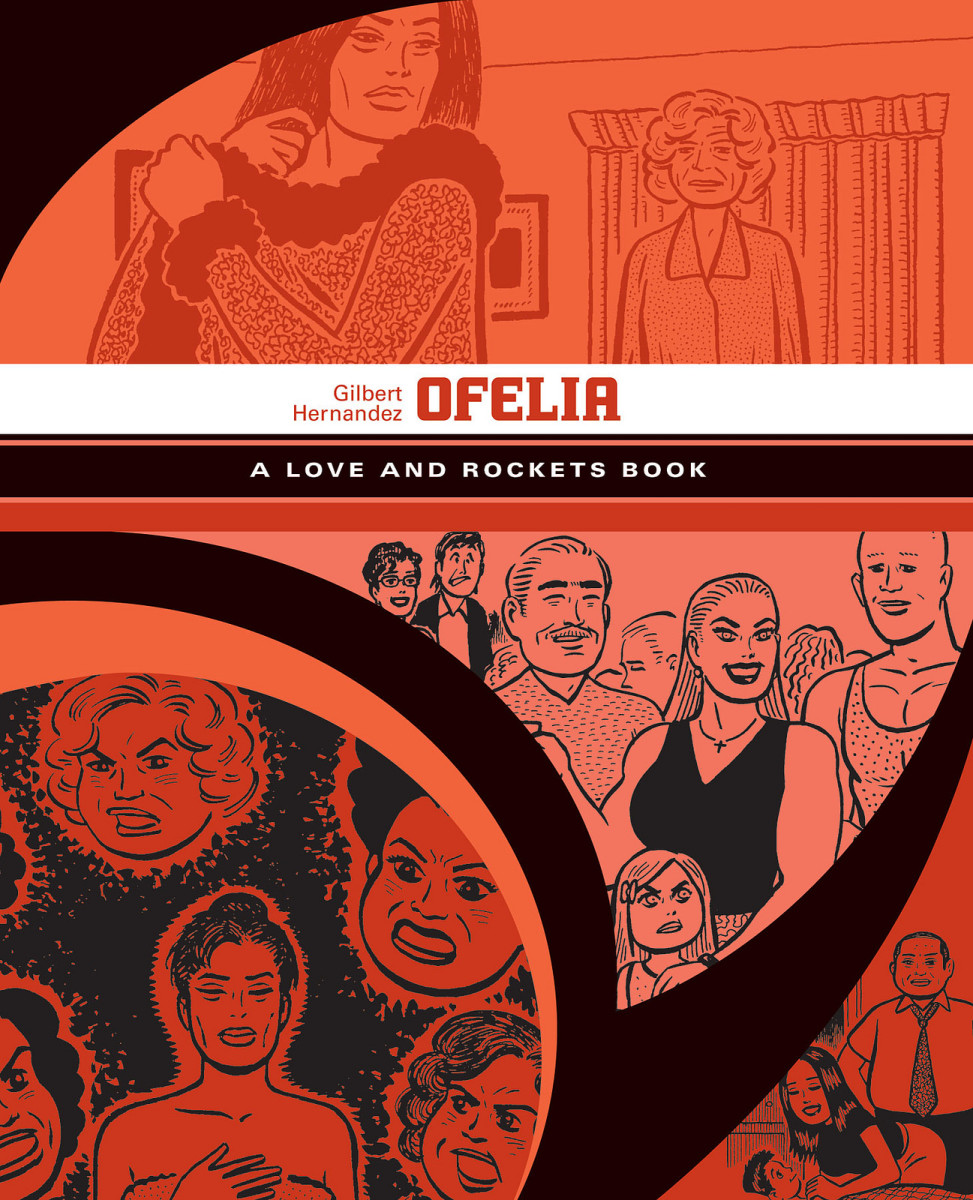

In 1981, at a time when the comics landscape consisted mainly of children’s, superhero, and genre comics, Gilbert, Jaime, and Mario Hernandez revitalized the medium with their character-driven tales of life in California and Mexico in their series Love and Rockets. A mashup of superheroes, sci-fi, and sometimes romance, the work of Los Bros Hernandez, as they’re often known, signaled a significant transition in comics, one that expanded the possibilities of the form and revealed not only that comics need not be solely for children but also that the medium could offer emotionally nuanced and keenly observed literary narratives.

Love and Rockets, published by Fantagraphics, was principally produced by Gilbert and Jaime. Whereas Jaime tapped into LA punk culture, Gilbert focused on more universal motifs: coming-of-age, familial drama, and romantic love in the mythical village of Palomar. The Mexican American brothers featured Latino and Latina characters in their comics at a time when the industry was comprised almost entirely of white men. In Love and Rockets, Gilbert introduced one of the most memorable and complex female characters of the era–the fierce Luba, whose matriarchal presence invigorated Palomar and, more broadly, the world of independent comics.

Gilbert told MELUS that diversity in comics characters became one of his missions: “My goal is to tell stories that are engaging and entertaining for a general audience–but specifically to humanize Latinos, to give a different angle on Latinos from what is normally given in pop culture.” Artists of various genres found inspiration in Love and Rockets, including Junot Diaz. He said of the Hernandez brothers, “In many ways, they were my essential inspiration and an important model for me in my art.”

I spoke with Gilbert over the phone from his Las Vegas home. We discussed how film and TV influenced his narrative storytelling, how he continues to let his character Luba evolve, and why young artists should unplug and learn how to draw.

–Grace Bello for Guernica

Guernica:What was it like when you first got started in comics? Were you trying to make a career out of it? Were you experimenting?

Gilbert Hernandez: All of the above. I was in my early 20s. I had been working odd jobs here and there. I wasn’t sure what I wanted to do with my life. I always wanted to pursue either music or comics, so when the opportunity came [from comics publisher Fantagraphics] for my brothers [Jaime and Mario] and I to make a comic book together, we jumped at the chance: “Let’s just do it and see what happens.” Really, we weren’t sure where we were going to go with it. We thought our work was good enough to be out there, but we didn’t know that the response was going to be pretty good, pretty quick.

We had self-published the magazine, but we didn’t have a way to distribute it. I happened to send a copy to Fantagraphics. I had heard they were interested in publishing alt comix. I sent them a copy, forgot about it, and, a little while later, Gary Groth, the publisher, wrote back, “We’d like to publish your comic.” So that’s pretty much how it started.

Once we got going on the Fantagraphics version of Love and Rockets, our encouragement was constant. People wanted us to do more, do more. Thirty years later, here we are.

My brother Jaime–more than I did–emphasized the punk rock element and put that in the comic. That’s what got the biggest response.

Guernica: I wonder what the reception was for Love and Rockets back then. At the time, it was radically different from what was already out there. There were superhero comics, there were genre comics, and then there were underground comics. Love and Rockets seemed to stand alone as a character-driven series.

Gilbert Hernandez: It was a hybrid of all those things: superhero comics, underground comics, science fiction magazines. What we seemed to be best at was exploring characters. We had all the imagery–superheroes and rocket ships–but it was more important to write complex characters. Readers gravitated toward them right away.

Our main fans noticed the artwork, too. They really loved the covers, which were parodies of superhero covers. When we started Love and Rockets, it was the early 1980s, and we were still in the LA punk scene. So my brother Jaime–more than I did–emphasized the punk rock element and put that in the comic. That’s what got the biggest response. He continued in that direction. The comic slowly built a following–but because we pursued what we wanted to do, not what other cartoonists were doing.

Guernica: What did your hometown look like?

Gilbert Hernandez: It was a safe place to grow up. Simply, it was a small, agricultural town. We lived in a middle-class neighborhood in the 1960s. Nothing going on, other than kids playing baseball. When I was growing up, I saw my neighborhood as the world, which meant going to school or hanging out with friends or having relatives coming over.

We got a lot of, “Oh, you stayed in Oxnard? Why didn’t you move to New York?” Because we didn’t have to.

Guernica: As a cartoonist, what tools do you use?

Gilbert Hernandez: Just pen and ink. It starts out with a piece of paper, a pencil, and an eraser. That’s it.

Guernica: That’s so pared-down. Younger artists tell me they use various kinds of software and a Wacom tablet.

Gilbert Hernandez: Well, they do that because they never learned to draw. It takes time to learn to draw. It takes years, not a few weeks.

Guernica: Did film and TV play a role in teaching you about visual storytelling?

Gilbert Hernandez: Oh, absolutely. I’ve noticed that a lot of my peers, a lot of the older cartoonists, that’s how they grew up [learning about storytelling] as well. They’re more interested in narrative structure. I notice a lot of younger artists have difficulty telling stories. They might have short stories where they express themselves well, but they don’t really know how to tell stories with characters. That [craft] just passed them by. But, you know, back in the ’60s and ’70s, there were no personal computers. There weren’t those kinds of distractions. You watched whatever they stuck on TV. That was it for accessible visual arts. But now there are so many different outlets. Nobody has to watch anything if they don’t feel like it.

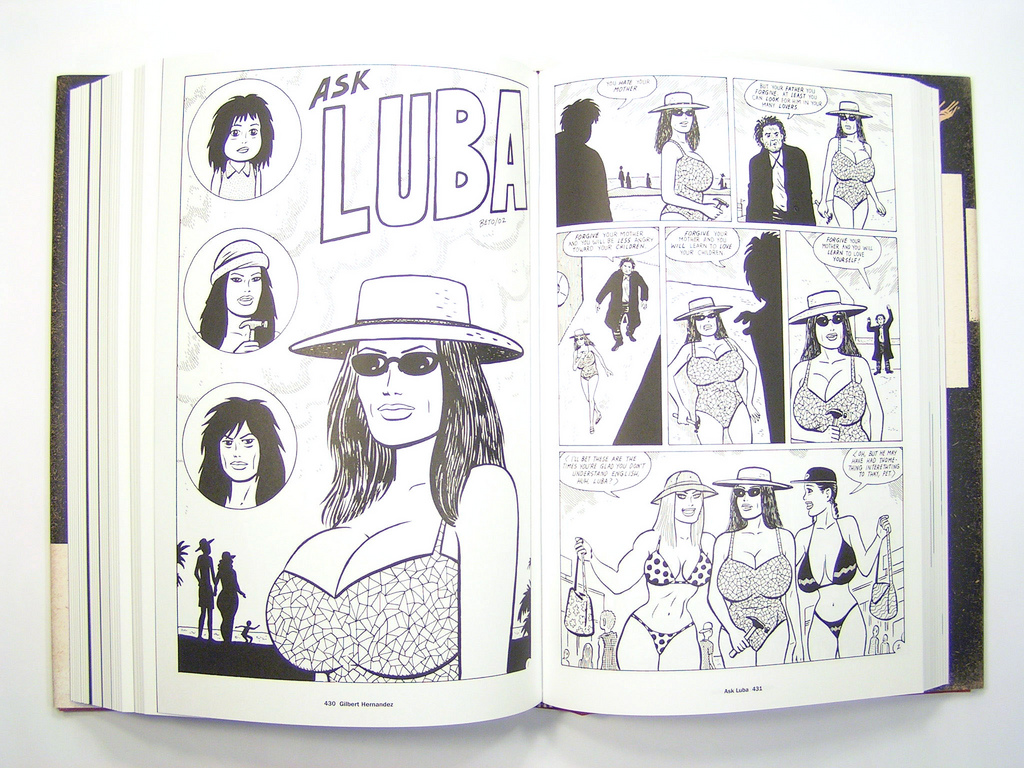

Guernica: To go back to Love and Rockets, I’m really curious about your most prominent character, Luba. What inspired you to create her, and what was your approach when you first started drawing her?

Gilbert Hernandez: Originally, Luba was in the first version of Love and Rockets, and it was a science fiction story. A lot of European science fiction stories were coming to America as reprints, and that was the first time we’d seen those in America, in a magazine called Heavy Metal. The publishers were trying to sell the magazine as sexy comics. As a young man, that piqued my interest because I was bored with the mainstream superhero comics; they were completely sexless. I was pleased that, for the European comics crowd, sexiness was welcomed. They were actually blasé about it.

When I was doing the science fiction story, I just took that approach. I created a voluptuous woman as the villain. She’s very temperamental, and once I started writing her character, she was just fun to write, as well as draw. She evolved that way. I was also able to put my own personality, my own gripes, into her head. There was a safety to creating a character who looks nothing like me. [laughs] That tends to liberate a writer. When a character looks nothing like you, you’re able to put yourself into them.

So that’s what happened, and that’s how that character evolved. I took her out of that science fiction milieu and put her in Palomar, which was a more down-to-earth setting. She worked perfectly there. It just fit.

Readers accepted the characters as reflections of themselves, even if they didn’t look like them or live like them.

Guernica: Over the three decades that you’ve been doing Love and Rockets, has your approach to Luba changed at all? Did you start to view her character differently as she aged and as the storylines progressed?

Gilbert Hernandez: Yeah, she’s mellowed with age. I’ve seen that most people change as they get older. At a certain age, people start to explore different areas of their personalities. So I did that with Luba; I decided to make her as complex as I could. A lot of her rage had come from defensiveness. She’s the same person now, but she doesn’t have the outbursts that she used to. Although those [scenes] were probably really enjoyable for the reader, I had to move on. That’s difficult, because she’s probably the best-written character I’ve created.

Guernica: Going back to what it was like when you first started, I’m curious about what it was like as an artist of color working in an industry dominated by white folks. What was the reception for this comic filled with Latino/a characters? What were you trying to achieve?

Gilbert Hernandez: Well, that’s all I knew. I knew what it was like to be slightly on the outside, growing up Latino in America. It wasn’t an issue; it wasn’t an agenda. It was more like, “This is what I know, and I know it’s not already out there [in comics].” It’s not in the mainstream pop world either. It would be original.

I wanted to dispel stereotypes. Not that that was my end goal, but there were certain aspects of being a Latino that was not–is still not–represented in pop culture. Since I had the opportunity, I thought, “Well, I’m just going to do it the way I see it.”

Readers accepted the characters as reflections of themselves, even if they didn’t look like them or live like them. That was another reason I emphasized the characterization. Anyone could identify with the human aspect of the characters.

Guernica: You’ve said that your latest comic, Blubber, is a story from the id. Was Robert Crumb a big inspiration for you?

Gilbert Hernandez: Oh, absolutely. To this day, he’s one of my favorite cartoonists. For all his faults, he put himself out there. But at the same time, he had the skill to do it. He wasn’t just some crazy guy flailing around. He could come up with a story fueled by his passions and put it down. That’s a double-whammy right there. If you have the imagination and the chops, you can be around for a long time in comics.

He’s not doing so many comics now, because he’s 70 years old, and he worked on the Bible [The Book of Genesis Illustrated] for five years. That wiped him out. [laughs] He’s been doing comics since the late ’60s, so he’s taking a break. But I’ve still got a lot of energy. I don’t pay attention to how old I am, and I just keep going.