I find myself in constant want for contemporary stories that dare to tackle the philosophical through the absurd. The personal can be absurdly philosophical, yes, but the era of stories that explicitly present themselves as absurdist philosophical inquiries, as Barthelme’s so often do, seems to be somewhat more behind us than ahead, with the brave, daring exception of the narratives of Dolan Morgan, which endeavor to make felt nothing less than the material void contained within each of our chests. In his newest collection of stories, Insignificana , released last month by indie publishing powerhouse Civil Coping Mechanisms, Morgan creates twenty-two whole, other worlds. In “Timeshare” various people take up residence inside the body of a deer. In “Celebrity Training, Mon Amour: Audrey Hepburn” the deranged celebrity, not at all how we know her, eats “her entire body in hopes of better understanding her own physicality.” In “Stable” a young, unlucky-in-love millennial becomes pregnant with a portion of the apocalypse. Within all of these stories the stakes and the questions being asked are impossibly grand. In the era where the thirty-five-page divorce story reigns high, here Morgan is, making us question if we even know where our body ends and the rest of the world begins. These stories often caused me to look up from the page and touch my own flesh just to be clear that my body was still material, and hadn’t, unbeknownst to me while I had been inside Morgan’s head, somehow combined into a single substance with the desk.

I read Insignifcana brutally fast, in a single sitting—which I’d highly recommend. The violence of being thrust so quickly from one conceit, one absurd philosophical line of questioning, into the next, was wildly alarming in a way that makes you remember the power that fiction, when executed with precision, can possess. The below interview is excerpted from a conversation that Morgan and I conducted over the Internet. While I wrote, I sat in Vanderbilt University’s Peabody Library, which has lime green interiors, colonial crown molding, and an exhibition of past students’ time capsules from the 1970s. While Dolan Morgan wrote, I have no idea where he was, but I imagined him blurred and bodiless—both at his computer typing away and nowhere all at once.

—Rita Bullwinkel for Guernica Daily

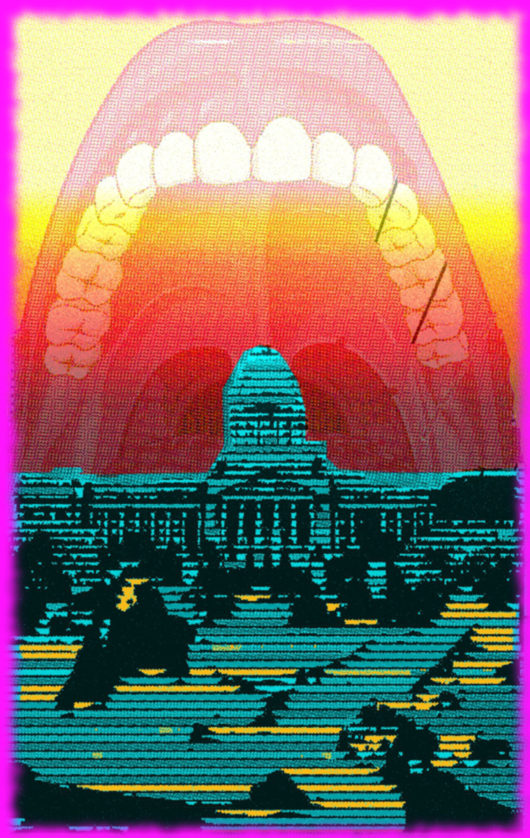

Guernica: Each of the stories in Insignificana is accompanied by a piece of visual artwork. In these images objects assume faces and faces become objects, which is brilliantly imitative of the way much of your fiction within the collection operates—humans blending into and inhabiting the inanimate, the inanimate becoming sexualized and alive, the alive becoming reduced to a mere un-action wielding container. Thus I imagine that life as Dolan Morgan might be somewhat comparable to the experience of looking at these photographs—objects that look like living or other things: a mop with a face, an “angry” onion, a zipper that looks like a fish, a sexy lounging vegetable, and some bread slippers too.

Is your life like these photographs? When you walk around deep into the night do the un-living become alive and the alive become object? Does everything that enters your retinas assume some sort of story, agency and face?

I am constantly distracted by the point at which our assumed agency intersects with the intractable forward motion of the objects and processes that surround us.

Dolan Morgan: Ha! I do believe my life is like these photographs—but not because they reflect how I witness the objects around me (unfortunately, I don’t see any agency in inanimate things, despite how much I’d like to). Rather, and sometimes sadly, I often see the inanimate in people and myself. It makes me feel a bit like a jerk—because I sometimes have trouble distinguishing where the environment ends and people begin. As such, these photographs far better reflect how I see myself than anything else: a bunch of lifeless material sort of smashed together with a ridiculous face tacked on for good measure, angled just so to trick us into thinking there’s life underneath. Junk plus illusion.

Guernica: In “Dafne: Cavatina” the narrator states:

“I am small and end abruptly where the rest of the world begins. Giants are enormous, complex, and thrust defiantly into the world, as if their bodies wished never to end, to devour the point where the world begins. Giants, simply by being so large, achieve this blurring between body and world in a way that I can never hope to replicate.”

As a non-giant who also has difficulty understanding the parameters of my own body, how can I ever hope to begin to know where my body ends and the rest of the world begins? Do you have any tips for non-giants who are also having difficulty discerning the boundaries of their own bodies?

Dolan Morgan: Yeah, this is a confusion I experience often. Like every day. I am constantly distracted by the point at which our assumed agency intersects with the intractable forward motion of the objects and processes that surround us. We’re here, but so is all this stuff. Tables, chairs, Cheetos, cars. I mean, the world is 99.9999% lifeless junk, and so I have the suspicion that as a matter of probability, we are more like that stuff than our notions of individuality and humanity would have us believe. So much of who we are and what we do is the product of circumstance, chance, and accident, and so there’s a certain magic required to see any portion of ourselves as divorced from that parade of context which envelops us. In so many ways, then, asserting a belief in our own agency is ultimately an act of faith. Which is fine, of course. I like wishful thinking and leaps of faith. But limiting that faith to our own lives alone? Seems a gravely arbitrary line to draw. Why stop there? Why impart an unfounded magic to this particular mass of nothingness (ourselves), and not some other things (tables/chairs/cheetos/etc)? Many of the stories in Insignificana are attempts to extend that same faith beyond our own bodies and into the world of other objects and useless things. For me, this is a search for some humanity. That is, if I can imagine the love and worry of some random objects or numbers, then I can imagine the same of a person or myself. If I can empathize with the inner life of mass-market products, then I can empathize with the inner life of the people around and within me too.

And, of all of the photos here, I most identify with the “bread slippers.” Here’s why: I once owned a pair of bowling shoes. I loved them. Or at least, I wore them. Often, and to a fault. I have an unfortunate habit of wearing shoes until there are very large holes in the soles—and then continuing to wear them anyway. Which is terrible in the rain. They fill up with water. Socks get all wet. It’s awful. Somehow, my love of routine and lack of money always outweighs the profound level of discomfort that comes from traipsing around in flooded footwear. But I want to tell you about the point at which the scales finally tipped, the point at which I abandoned those particular shoes. It was the eve of a hurricane in NYC. I was to spend the night at my friend’s home, where we would pool our non-perishable goods. While walking around the neighborhood to gather supplies, it began to rain. Hard. I looked at my shoes and knew the fate that awaited me and my poor feet. Something must be done, and quickly. I did not, however, choose a good something.

Now, side note: at one point in my life, I’d heard the myth that somebody used potato bread to absorb their sweat (tucking it into their armpits, their bras, their shorts). Why not? Do you. So, on a whim, I bought some potato bread and lined the bottom of my shoes with it—as an attempt to plug the holes, to keep the water out. I can tell you that this plan didn’t work. I mean, I knew this plan wouldn’t work. Rather, I just ended up with horribly wet shoes that were also filled with bread. Wet, filthy bread. I ended up so uncomfortable that I decided to walk back to the safety of my own home before the hurricane arrived. What happened instead, though, is that I walked into the street at the very moment that the hurricane hit the city. I was delirious. Immense wind, endless rain. Hole-rotted bowling shoes filled with bread. And water. Objects flew past my head and the sky opened up, enormous and vivid. It was gorgeous! I’ll never forget it. And of course, the next day, I threw out the shoes. It was an obvious choice. Simultaneously inevitable and entirely my fault. The reason I bring this up, though, is because I don’t think that this decision to throw away those horrible, ruined shoes is distinctly different from any other choice in life; rather, there’s always a hurricane and a myth and a mistake, and we’re always soaked, in one thing or another, and forever headed home, so of course we throw out the shoes. It’s always both inevitable and our own responsibility. It doesn’t make sense, and it doesn’t have to, but meanwhile, there’s a sky and some beauty.

Guernica: How did you go about making the visual art pieces for each of the twenty-two stories in Insignificana?

Dolan Morgan: Almost by accident! I have an open source image manipulation program called GIMP, and I pretty much drew a lot of circles and lines and then tinkered until it was time for bed. It’s a first for me, illustrating a book. I had fun. Then I went to sleep.

Guernica: How do you understand the relationship between image and text?

Dolan Morgan: One and the same! They’re both little scratches made with hands onto the big rock outside our heads.

Guernica: In both “Timeshare” and “The New Middle Class” things live off of and in symbiosis with other things. Have you ever been infected with a parasite? Do you fantasize about other living things taking up residence within you? In “Timeshare” a man moves into the body of a deer and immaculately decorates its interiors. How would you decorate the interior of your own body? What type of flooring (area rug or wall-to-wall carpeting) do you see when you visualize the cavity in your chest?

For one, people are just absolutely filled with bugs and goop. Our bodies have roughly ten times more bacteria than human cells. So right off the bat we’re less ourselves than something else.

Dolan Morgan: I don’t think I fantasize about being infected with parasites or having other things take up residence within me. Mostly because I understand those things to already be the case. For one, people are just absolutely filled with bugs and goop. Our bodies have roughly ten times more bacteria than human cells. So right off the bat we’re less ourselves than something else.

More than the bacteria, though, I tend to see everything as winnowing in and out of everything else. People and their environments (all of the things around them, including places, objects, other people, events) are in a constant state of dialysis. I mean, I often feel like a parasite thrust into the spaces where I am, unjustly transforming things for no good reason. Likewise, I feel the world worming its way through me, often uninvited and to unknown purpose. I want to say, “Get out of here, World!” but I know that if it goes, then I go too. We’re eating each other.

This brings me to something that I do feel especially infected by: a kind of shared, amalgamated objectivity brought on by a constant connection to others via the internet and social media. I don’t by any means hate the internet or feel nostalgia for a time without technology. But I’ll give you an example of what I mean. When I watch 1970s horror films, I love the architecture and settings. Carpeted suburban homes, enclosed spaces. Great sweaters. Plus ghosts, magic. Always in these movies, someone is entering a room. They can’t be stopped. Of course, terror awaits. But mostly in the mind. And here’s what strikes me now as I watch these films: when the characters enter those rooms, they enter them in a way that I no longer can. When the protagonist in the 1970s horror film steps through the door alone, he or she is truly alone. That is, a kind of solipsism is at the heart of what it means to enter a room in that kind of film. The person is in that space and there is only that space—and the resulting possibility of magic. They have no recourse to the world around them, only to their interiors, where magic and ghosts come from. But when I enter a room, I enter it with the rest of the world alongside me. With a few thousand people (at minimum!) and their thoughts and opinions in my pocket. And if you think of every situation we encounter as a kind of room, then this analogy becomes somewhat grim. Every new experience I encounter is mitigated by how others are experiencing it simultaneously. A historical event, a controversy, a new movie. This is primarily a good thing—I feel lucky to have such quick access to a wide variety of differing interpretations of world events and issues, and I think it ultimately makes me more informed and grounded and possibly a better person.

However, there’s something sinister to it as well. A certain level of delusion, however brief, is subtracted from experience. And I’m a fan of delusion. And ghosts. And magic. And by ghosts or magic, I mean the impossible. Of course, the impossible is always impossible, but briefly it can be possible when you are alone. I think we all know this and have experienced it. As children at the very least. But my constant and immediate access to other minds dispels those ghosts. Even the understanding that people are out there, ready to react, is a kind of exorcism of fantastical or delusional thinking. So some magic is subtracted from the universe by the infection of our shared rationality (if you can call it that) and assumed objectivity, both of which are collectively gathered and agreed upon moment by moment. I don’t think this parasite (ourselves) is going anywhere any time soon, either. Rather, it’s probably just going to get bigger and fatter. Until it is like bacteria and we end up being more ourselves than ourselves. So, in the meantime, I try to cast spells in other ways when I can. Fiction is one kind of spell.

Guernica: Do you know what a bot worm is? Have you seen the ways in which one can be extricated from human flesh?

Dolan Morgan: I know about bot worms! I do not like them. I have seen the videos. I do not want one. Anyone reading this who is not familiar—do not endeavor to become familiar. Save yourself. Especially, do not look up videos of a botfly larva being removed from someone’s eye. You don’t need that in your life.

Guernica: Where does the absurdist’s heart live? Where does your heart live? As in, at approximately what address, and in what type of home?

Dolan Morgan: I can’t say where the absurdist’s heart lives, but if I had to guess, I’d probably go with Potwin, Kansas. There’s one particular farm there plagued by unfortunate incidents; and so it seems a good fit. For example, in a recent Fusion article, Kashmir Hill writes that for over a decade the people living on the land have unjustly been “accused of being identity thieves, spammers, scammers and fraudsters. They’ve gotten visited by FBI agents, federal marshals, IRS collectors, ambulances searching for suicidal veterans, and police officers searching for runaway children. They’ve found people scrounging around in their barn. The renters have been doxxed, their names and addresses posted on the internet by vigilantes. Once, someone left a broken toilet in the driveway as a strange, indefinite threat.” There’s nothing about the farm or its tenants that would justify any of this, either. It defies understanding. The tenants are just people, going about their lives in the same way that anyone else might. Yet there are larger circumstances at work that have direct and disproportionate impact on their existence. Or, perhaps “larger” isn’t the correct word. Rather, one small decision may be the culprit: someone at a tech company rounded an unwieldy decimal up to the nearest whole number, and as a result the farm receives this onslaught of strange scenarios. (It’s like that scene in Terry Gilliam’s Brazil where a typo gets a man abducted and assassinated by his government.)

As for my heart, I’d say it lives where everyone’s heart unfortunately lives: the past and the future at once, which are the same place.

Specifically, though, in this case it’s not a dystopian regime but an organization that links IP addresses to geographic locations (which is especially useful in all manner of criminal inquiries—think stolen phones, court evidence, etc). When the company’s efforts can’t correlate an IP address to a specific home or business, their method defaults to a dummy location, usually the “center” of some area. And our Potwin, Kansas farm is located at the exact geographic center of the United States—or at least when the coordinates are rounded off. As a result, all manner of national incidents feed into their home; “there are now over 600 million IP addresses associated with that default coordinate.” And, so, since I can’t locate the exact address of the absurdist’s heart, I too will default to this Potwin, Kansas farm. I’m assuming they can handle one more thing. It feels especially appropriate given that the people living there are beset by scenarios brought on by the minutiae of some distant system’s useless and unimportant inner workings. Despite what they do or don’t do, and despite whether they’re good people or bad, and despite whether they believe one thing or another about themselves or the world—a set of unrelated, entirely mundane and incidental circumstances coalesces to form the parameters of day to day living. Sounds like a Tuesday afternoon to me!

As for my heart, I’d say it lives where everyone’s heart unfortunately lives: the past and the future at once, which are the same place.

Guernica: How do you understand the emotional core of the absurd? How does it mimic your experience of living in a human body?

Dolan Morgan: That’s a tough one. At its center, I might put two things: 1) we are wrong about everything, and 2) this isn’t inherently bad.

Let me give you a sort of example. I love optical illusions. I especially enjoy the ones that demonstrate the fallibility of our senses. My favorite is of a chessboard with a shadow cast across it. On this image of a chessboard, one of the “black” squares and one of the “white” squares is in fact the exact same color. But people’s eyes simply cannot process that reality. When I look at it, I am reminded that pretty much everything about our sense of being in the world is a lie that our bodies tell our brains and vice versa. We are ill-equipped to interpret the universe around us. We can’t even understand the picture of a chessboard, let alone anything else. We are like a dog I used to know: always scratching and trying to dig (for bones?) in a tile floor. There in the kitchen, the dog did the only things it knew how to do, despite how inappropriate its behaviors were for the situation at hand. And, of course, it couldn’t even conceive of how little sense those choices made, but a dog goes on like that anyway. What else can it do? Anyway, that’s me, basically.

That all sounds pretty cynical, but an absurdist’s job might be to articulate the ways in which this scenario is okay. To elucidate not only the scenario itself, and its accompanying pointlessness, but also the joy within it. I am bored by the old notion of fear and anxiety that so often accompanies the absurd and the void. Frankly, a fear of the void confuses me to no end. Rather, we should be especially afraid, not of the void, but of what we know, or think we know, and how we attempt to fill other things with that knowledge. People often describe a “fear of the unknown”—but we are not afraid of the unknown or uncertainty. No, we are afraid of what we shove into the open space of that uncertainty. We put our own nightmares into the night’s silence, not the other way around. There’s a reason why we say “oh it was nothing” in great relief when we are no longer afraid: nothingness is not scary. Instead, there is terror in meaning alone.

Likewise, the ecstasy of “pure reason” is a myth. The joy to be found in solving a math problem, for example, is not the feeling of “finding a new rule! yay!” but instead the feeling of extant rules and constrictions falling away. There’s nothing quite like seeing a past system of reason come undone. Though it may lead to the foundation of new rules and structures, that moment of irrationality is still real (no matter how quickly it sublimates into reason) and it is still the only way I understand ecstasy. I mean, that dog loved scratching those kitchen tiles. Me too.