This is Part I of a two part homage to the strength and beauty that is Paris, its cultural diversity, its artistry, and its role as a center of revolution and enlightenment-then, now, and always.

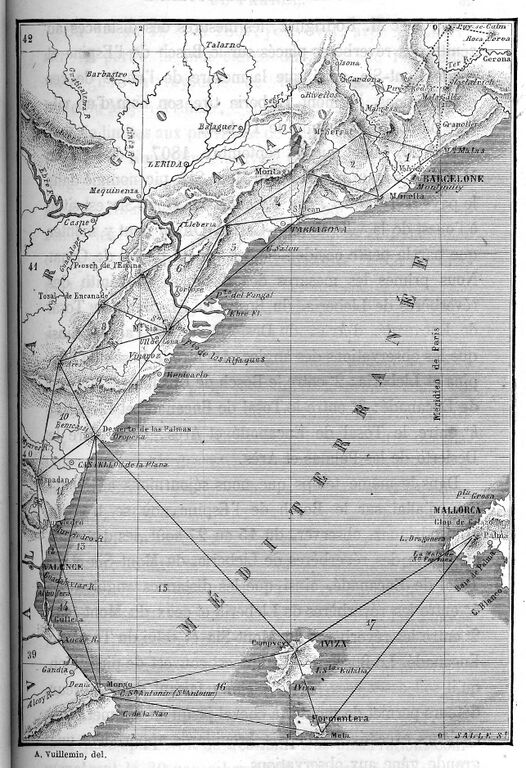

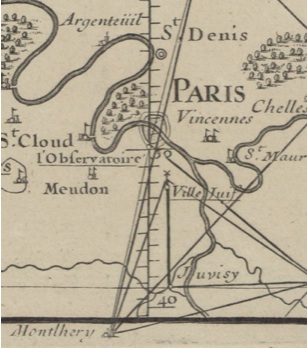

Among longitude lines, the Paris Meridian is a diva with a long and glorious past. From 1678 to 1884 she reigned on maps as the Prime Meridian, 0 degrees, the longitude line that divided east from west and from which all other locations were reckoned. Her address is now 2 degrees 20 minutes east, a bit of a come down, although she hasn’t moved. In her youth, her measurements were calculated by teams of scientists triangulating north and south from Paris. This was scientific enterprise on a grand scale, and even, we could reasonably argue, the first project of Big Science.

I had the rare good fortune to meet up with the Paris Meridian for the first time in her inner sanctum on the second floor of the Paris Observatory, a research institution closed to the public. We were living in Paris that year and my geographer husband put our names on a list of would-be visitors because he was interested in the role the Observatory had played in the history of French cartography. Months passed and we forgot all about it. And then one day we got a call: we would be allowed to join a guided tour on an upcoming Saturday afternoon. At the appointed time, we must be waiting outside the iron gates. This was in February 1996.

In the half-light of the gray winter day, we stood below one gold-framed oil portrait after another while our guide recited the astronomers’ dates of birth, death, and service to the Observatory. Handsome antique wooden and brass quadrants and sextants caused frissons of excitement among the other members of our tour, an amateur astronomy club, but I did not understand their use. The last room we were taken into, after climbing a white spiral staircase that wound upward with the simplicity of a seashell, was rectangular and traversed the building from north to south. The vaulted stone ceiling rose eleven meters above us, and the Paris Meridian was represented by a brass line inlaid across the stone floor.

The idea of an invisible line that circled the Earth and bisected the Observatory and the city of Paris like an arrow through a heart—that spoke to me.

A meridian is, by its nature, invisible, our guide explained. However, we could trace this meridian through Paris by following an artwork installed two years earlier by the Dutch artist Jan Dibbets. Leading us to the window, she pointed to a brass circle barely visible in the courtyard below, and then north, toward the center of Paris.

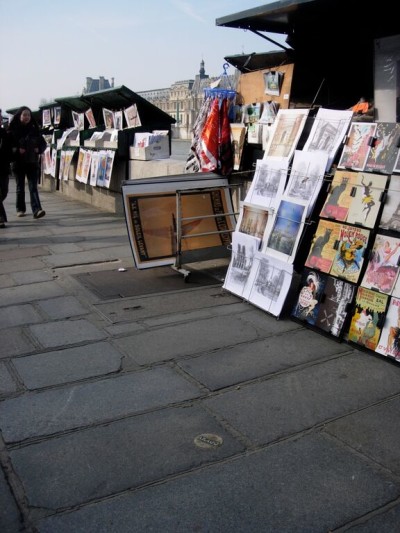

As we left the Observatory, we stopped and looked down at the little brass disk wedged between the cobblestones. It was about the size of my palm. On it in raised letters were N for north and S for south, aligned correctly, and across the center: ARAGO. This was the name of a former Director of the Observatory, one of the men in the gold-framed oil portraits we had craned our necks to see.

At the time, my husband apologized for wasting my afternoon on such a boring tour. I turned to him in surprise. The litany of astronomers had meant nothing to me, true. But the spare stone room with its brass line, the idea of an invisible line that circled the Earth and bisected the Observatory and the city of Paris like an arrow through a heart—that spoke to me. I knew nothing about astronomy. I had not even taken high school physics. But in that rectangular high-ceilinged room, I had felt the enormity of the questions these early scientists were asking. They stood at that same window, unable to see any farther through the old wavy glass than I could, and yet they set out to measure our planet. Inspired by their audacity, I set out on my own modest expedition into the history of science and the mysterious land of geodesy.

The early French scientists were determined to measure our planet, but where, on a round globe, do you start? It’s obvious where to put the horizontal line. It goes at the equator, a belt around the Earth’s rotund waist. From the equator, the zero line of latitude, you measure north and south with concentric rings. But to measure a sphere and pinpoint places on it, you need a grid, so you must also encircle the globe with lines of longitude that arc from pole to pole. Where do you place the first longitude line, the one that will be zero, the one from which we will count the degrees east and west? Where on Earth should you start?

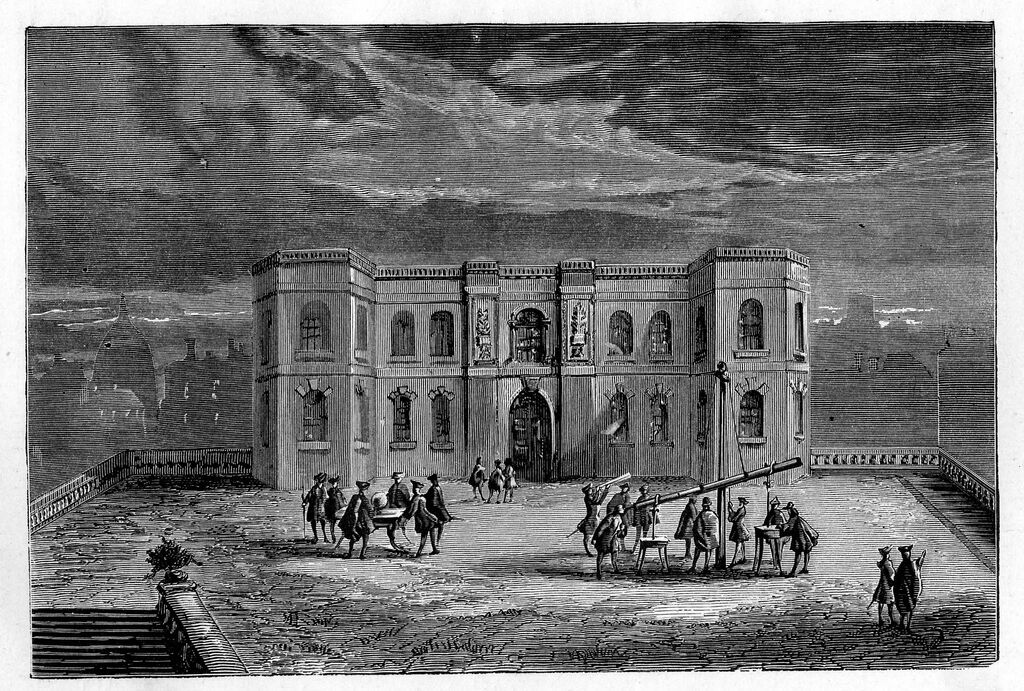

No matter who you are, the center of the world is home. For the scientists of seventeenth century France, the center of the world was their home, Paris. On June 21st, the summer solstice and longest day of the year 1667, five savants of the newly-formed Academy of Sciences piled into a carriage with their sextants headed for a piece of land south of town given them by the King. At noon, they measured a line on the earth perpendicular to the equator, a meridian, and marked it on a stone. Above it, oriented to the four cardinal directions, they envisioned building a royal observatory. The royal finance minister, Jean-Baptiste Colbert, envisioned using the results of their research for French imperial commercial ventures.

Nearly three hundred and fifty years later, the Paris Observatory is the oldest observatory in the world still in daily use. The meridian that bisects the building became the Meridian of Paris. For two centuries, this longitude line served French scientists as a geodetic laboratory. As they extended its measurement south and north, they investigated competing theories of gravity and the shape of the Earth. Was our planet slightly pointed at the poles like a lemon (they thought it was) or slightly flattened like a tangerine and like Jupiter, as Isaac Newton argued? After seventy-five years, their measurements supplied the answer, and in 1744, although it must have been painful, they conceded that their English rival, Sir Isaac Newton, was right. The Earth was flattened at the poles. Their measurement of the Paris Meridian had proved his point.

Not just any meridian of course, but their meridian, the Meridian of Paris.

In the late eighteenth century, French scientists pioneered the concept of a standardized, logical system of measurement based on nature, the meter. Their meter would belong to everyone and could be used for everything from scientific observation to selling cloth in the markets. Like France at that time, the meter was revolutionary; like the scientists, it was rational. All mankind, they felt sure, would quickly embrace its use, advancing both science and commerce. They decided the meter would be one ten-millionth of the length of a meridian from pole to equator. Not just any meridian of course, but their meridian, the Meridian of Paris.

On French maps, the Paris Meridian was the Prime Meridian and the longitude of every place on Earth was calculated in degrees east or west of Paris. But cartographers from other countries used other meridians, and in 1884, an international conference held in Washington, D.C. chose the meridian that passes through the British Royal Observatory at Greenwich as the international zero degree of longitude, the Prime Meridian.

“We accepted,” an archivist at the French geographic institute, IGN, said with a sigh. “But,” he added, “on one condition, that the British accept the meter.” He smiled wryly. “And have they?”

Britain officially instituted the metric system and began phasing out imperial units in 1965; it appears to be a long and painful process. As was giving up the Paris Meridian for France—it lingered as the Prime Meridian on French maps until 1911. Even now, the Paris Meridian appears on some IGN maps of France. This is necessary, the archivist explained, for historical research. He assured me that planners and researchers come into the IGN map library every day to align historical maps with contemporary ones. “We have no intention,” he said quietly but firmly, “of throwing away two centuries of French cartography.”

But aside from these few maps, the Paris Meridian has become a historic rather than a geodesic landmark. The meter is now derived from the speed of light, and points of longitude and latitude are triangulated using navigational satellites. The Geographic Positioning System (GPS) is so precise that it takes into account time as well as space and the slow edging apart of the continents known as continental drift. WGS84, the American system, places zero longitude where the Greenwich Meridian was at midnight on New Year’s Day in 1984.

The year I met up with the Meridian I was living in Paris, spending every spare moment walking the city. I had been a meanderer, a flaneuse, in the venerable Paris tradition, going wherever my feet took me. But once I was oriented to the Meridian and the four cardinal directions, I became a pilgrim. As I walked, I pictured the line under my feet extending south to West Africa and north to the Arctic Circle.

Sometimes the inhabitants of this territory spoke of le méridien de Paris. But other times my informants used the feminine, la méridienne de Paris. I had seen both on old maps. In fact, French astronomers use the masculine noun meridian to refer to an invisible line of longitude, any of the multitude of invisible meridian lines at right angles to the equator. But when un meridian becomes visible or tangible, it undergoes a gender change and, voila! becomes, une méridienne! What causes this transformation? A line on a map or globe, the shaft of sunlight on a sundial at noon, a trail of brass medallions.

If you don’t stop at too many cafés, you can hike across Paris on the Meridian in a day. Starting at the northern edge, your trek will take you through a market frequented by African immigrants, the hills of Montmartre, the Palais Royal, the Louvre Museum (there are medallions both outside and in), the Luxembourg Gardens, and Parc Montsouris. The first time I trekked it in 1996 with my geographer husband, we found all but eight of the roughly one hundred and fifteen medallions accessible to the public.

South of the Observatory, behind its garden, the Meridian passes over a massive stone pedestal taller than my head. Engraved on the stone is F. ARAGO 1786-1853. Souscription Nationale. The pedestal once supported a larger than life-size bronze statue of the astronomer-physicist François Arago. In any other city, an empty pedestal might raise questions, but in Paris, its meaning is clear: it speaks of occupation and collaboration.

When Nazi Germany demanded copper from each occupied country for the war economy, most of Europe sent its church bells, but Vichy France had close ties with the clergy and deported its bronze statues instead. In provincial towns, people protested the removal of their hometown heroes, but Parisians had so many statues that few protests were raised, and city officials seized the opportunity to declutter Paris from the statuemania of the nineteenth century. Only five bronze monuments within Paris were classified as national treasures worth saving. François Arago, an obscure astronomer in an out-of-the-way location, bronze, and therefore eighty percent copper, was taken in one of the first roundups.

In 1986, on the two-hundredth anniversary of Arago’s birth, after the pedestal had sat empty for nearly fifty years, an association was charged with commissioning a replacement sculpture. The Dutch conceptual artist Jan Dibbets proposed leaving the pedestal empty and materializing the Paris Meridian with bronze medallions, with Arago’s name on each one. The astronomers were not unanimously thrilled with this proposal. They pointed out that the Paris Meridian was a collaborative scientific enterprise carried out by generations of researchers and that Arago came onto the project late, nor was the section he measured very long. An appropriate Paris Meridian medallion should be filled with names and the classical domed silhouette of the Observatory. But the curators on the committee championed Dibbets’s alternative monument and his intriguing Hommage à Arago was installed. Arago’s name was set down in over one hundred places–into sidewalks, between cobblestones, on the stone pedestal where his statue once stood, into the steps of the Luxembourg Gardens and the polished marble floors of the Louvre.

Most Parisians seemed to walk right over the little disks without noticing and so for ten years the Paris Meridian felt like a secret the city and I shared.

Each time I had the good fortune to return to Paris, I walked the Meridian, and each time, a few more medallions had gone missing; they vanished during sidewalk renovations or were pried up, I suppose, by souvenir hunters. I began to feel less like a pilgrim and more like a caretaker, checking up on my round charges. The bus stop on boulevard St. Germain? Still there. By the ping pong tables in the Marco Polo Garden? Gone. In front of the sex shop in Place Pigalle? Vanished. Next to the stall of the irascible bouquiniste? Still there, and still irascible.

In 2000, to celebrate the millennium, green metal disks were added where the Meridian crosses parks. The green disks are more visible because they are larger in diameter and installed on concrete posts, and they are reassuringly permanent. But they have the dull look of official signage; they lack the artistic charm of the medallions.

Most Parisians seemed to walk right over the little disks without noticing and so for ten years the Paris Meridian felt like a secret the city and I shared, an artistic treasure trail hidden in plain view. And then, in 2006, the Arago medallions became movie stars. Polished up for a supporting role in the film version of The Da Vinci Code, they played the fictional Rose Line. After that, Dan Brown’s fans sought them out. They even looked for them at the Church of St. Sulpice, which figures in The Da Vinci Code but is not on the Paris Meridian.

By then, twelve years after their installation, about half the medallions were missing. In some places, perfectly round holes in the pavement remained. Others had vanished without a trace. La méridienne was turning back into le meridian. After many phone calls I finally succeeded in getting an appointment with a city official in charge of monuments. “Ahhh, yes, the Arago medallions,” said the official, as her assistant moved stacks of papers to clear a path so I could enter the tiny office. “Yes, the city maintains monuments, but are the medallions in fact a monument?”

They were public art and the city of Paris cleaned and maintained other pieces of public art, I responded. So was the city planning to replace the missing medallions? She gave me a level look. “I certainly do not have that impression.”

I attempted to explain how much pleasure it gave me to walk the Meridian and how other visitors, if they knew about it, would enjoy it, too. Madame Monument threw up her hands. “Do you have any idea what it costs to change the light bulbs in Montmartre?”

I was about to reply that I did not. “You know,” she continued, “you really should speak to the Mayor. If he would give us the funding, we could replace the medallions, and perhaps you are just the person to persuade him.” And with that, I was handed my own stack of papers, given an encouraging handshake, and ushered out.

I should have gone to City Hall then and there and started a campaign for medallion replacement. I should have barricaded the Meridian and written a manifesto—Equal Rights for Conceptual Monuments! Instead, I headed to the Palais Royal for a restorative petit café on the Meridian.

Click here for Part II: Following La Meridienne de Paris and meeting François Arago.