By Ben Mason

In November Birgit Rydlewski, a member of state parliament in Nordrhein-Westphalen in western Germany tweeted candid details about a one-night stand, a split condom and the results of subsequent HIV-tests. A few weeks earlier, she had tweeted about being bored—while sitting in the parliamentary chamber. Defiant in the face of criticism from within and beyond her party, she replied (on Twitter, where else?): “Well did people really vote for us so that we would immediately become the same as other politicians?”

Ms Rydlewski’s tweets form part of a bigger story, about the rapid rise and fall of the party of which she is a member: the Pirate Party, which many people had hoped (or feared) would pioneer a new kind of politics for the internet age. Her question frames—in fewer than 140 characters—the contradiction that these failed pioneers, and others like them, seem unable to resolve: the very qualities that give them initial appeal hobble their hopes of making a lasting impact.

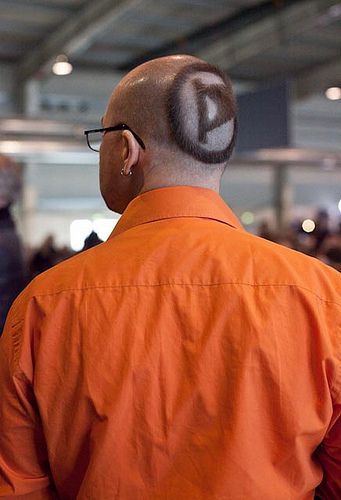

The Pirates are an international movement that started in Sweden. They stand for more direct democracy and oppose any kind of state regulation of the Internet or personal downloading. The movement seemed to have taken firmest root in Germany, where a proportional electoral system encourages smaller parties, and the electorate shows willingness between federal elections to vote against the big parties, which in any case have been perceived as representing a sclerotic old guard. Tilting at the disillusioned, it’s unsurprising that the German Pirates broke through first among younger voters: In the 2009 federal elections the Pirates received 2 percent of total votes cast, but 13 percent among male first-time voters.

A big part of the party’s appeal was in not being typical politicians, but “people like you.”

The past eighteen months have seen the Pirate Party emerge from obscurity into a serious political force—and then recede just as fast. In spring last year they had a string of triumphs in regional elections and one nationwide poll in April put them at 13 percent; after tumbling throughout the autumn, they received just 2.1 percent in the elections in Niedersachsen in January, and now oblivion beckons. Strangely, the reasons for their decline are largely the same as the reasons for their ascent: like a tragic hero, they have been brought low less by external misfortune than their own principles.

A big part of the party’s appeal was in not being typical politicians, but “people like you.” Their campaign ads showed pirated parodies of major brand advertisements rather than political slogans. Party representatives include a twenty-three-year-old who dropped out of law school to run for office and party vice-chairman Markus Barenhoff, who was arrested in October for marijuana possession. You may or may not think Ms. Rydlewski’s tweets were appropriate from somebody in office—a minority applauded her for breaking a harmful taboo and setting a responsible example. But there’s no doubt that in the eyes of most Germans she went too far—they don’t want their officials to be that down-to-earth, and perhaps when it comes to it they value old-fashioned decorum more than they’d thought.

What’s more, the Twitter incident blew up into a far greater fiasco than it had to because of the party’s structure. Fiercely egalitarian, the party has little hierarchy, and in the controversy that divided the party it was unclear who Ms. Rydlewski had to answer to—or indeed, if she had to answer to anybody.

If that incident exposed some cracks in the pirates’ ship, there is a far bigger hole which only became fully apparent in December when they tried and failed to fix it. A couple of radical principles is fine for a fringe group, but once they started winning seats, people began to ask the Pirates what they thought about, say the Euro-crisis, or energy policy, or pensions. The answer: nothing. Pirate policies cannot be imposed from above, they must be determined by consensus of members; so if the base has not come to an agreement on an issue, the leaders have no opinion. The party convention in December was supposed to solve this by setting policy, but it failed embarrassingly: since each of the two thousand members who came had equal right to speak, long lines formed behind the microphone and they got through only half of the weekend’s agenda. So to many questions the answer remained: “We have no policy on that.” For interviewers and the electorate, it didn’t take long for bemusement with the new approach to turn to frustration.

Nobody has pushed the idea of direct democracy further than the Pirates: they use the internet to maintain constant dialogue with their base, all party meetings are streamed live online—but even with their vigorous efforts, crowdsourcing has not been able to fill the space left in representative democracy.

I encountered something similar recently in conversation with David Babbs, director of 38 Degrees, a British-based group similar to MoveOn.org. The group campaigns on causes their members care about: opposing an unpopular health bill or the sale of national forests, to give just two examples. But then I asked whether he supported changes to the British constitution. More referendums and initiatives? A more proportional voting system? The repeated refrain: “I don’t know, we haven’t asked our members.” The Pirates had a similar idea—that party officials would act purely as mouthpieces for the base.

But what might work for a lobbying group has turned out to be less suitable for officeholders. Once in parliament, you’re called to vote on any bill that comes up—declining to have a position doesn’t really work. Without a clear party platform, MPs either just decide for themselves, which is even less democratically mandated, or they don’t vote at all. Mr Babbs described his organisation to me as “a vehicle for a large community of people who want to knock at the door of the powerful and say ‘listen to us’.” But the organization can’t stretch to actually being the powerful. Nobody in contemporary Western politics has pushed the idea of direct democracy further than the Pirates: they use the internet to maintain constant dialogue with their base, all party meetings are streamed live online—but even with their vigorous efforts, crowdsourcing has not been able to fill the space left in representative democracy, there are always too many gaps.

To return to the rhetorical question posed by Birgit Rydlewski, it seems those at the top of the party are eventually giving into pressure and, indeed, becoming like everybody else. There is a drive to “professionalize” from the proudly amateurish outfit they once were, and the leader and deputy will be expressing their own opinions without having to clear everything with the base. But they must see what their gamble means: in an attempt to win back support they are abandoning the distinctive features which made them appealing in the first place. Even if they do win seats in this autumn’s federal election—a dream that looks ever more distant—it will be a blow to the idea of a radically more direct, or “crowdsourced”, form of party politics, as they would be doing so within the confines of, rather than seriously challenging, the existing model of representative democracy.

Ben Mason is a freelance writer and journalist based in London. He has written for the Times in the Arts, Books, and Opinion pages, and is the winner of the London Library Student Prize 2012.