By Alissa Nutting.

Brought to you by the Guernica/PEN Flash Series

After college, Cora found it hard to get a well-paying job. Amidst stints as a waitress, a bartender, a barista, she came across a few medical testing gigs at a local research facility. Usually, these paid a few hundred dollars and required her to put a cream onto her skin that sometimes caused a rash and sometimes didn’t, or to put drops into her ears that caused variable levels of itching and/or burning and then required her to rank the intensity of itching and/or burning on a numerical scale.

There were many things in life that Cora found difficult, like choosing which scent and brand of dishwashing soap to purchase. If all bottles of dish soap cost the same amount of money, were all the same size and color and merely differed in fragrance, it would still, she felt, be a very hard decision, because there were many fragrances and they weren’t even in the same fragrance category: there was citrus, floral. There were atmospheric titles like Ocean Breeze that inspired their own line of thought and questioning altogether (for example, which ocean? How strong of a breeze?) But other tasks, such as being at a given place at least fifteen minutes prior to the time when she actually needed to be there, had never proved to be a struggle for Cora. The researchers noted and appreciated this, and it led to her being offered The Transparency Project.

The Transparency Project was not a one-day test but a hired, permanent job that would last until her natural death. When the leader of the research team said the word “natural” in the phrase “natural death,” he emphasized it in a very unnatural way. Each year, her paid salary would be the previous year’s average salary for all full-time workers in the city where she lived, in addition to a generous benefits package. All she had to do in order to receive this money every year until her natural death was come into the facility for monitoring and testing two days a week, eight hours per day. And have the operation. She could travel up to six weeks of the year, provided she allowed a monitor to meet her at a nearby hotel room for monitoring twice a week during each week of travel. If she were ever injured, comatose, or unable to come to the facility for any reason despite being alive, she would allow them to come to her for the monitoring. There would be legal documents outlining this permission. She would sign them.

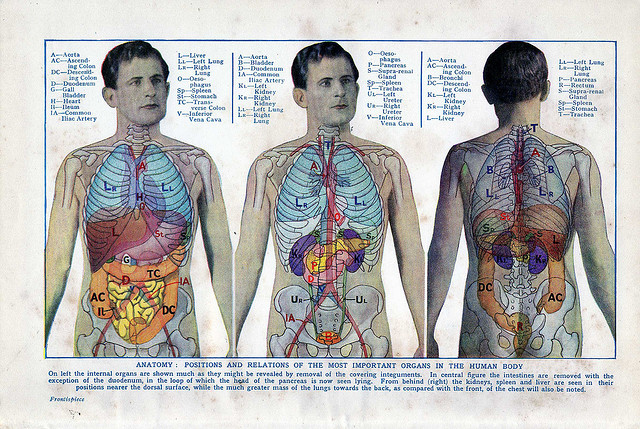

The operation would remove all existing skin and fat from a front section of her torso, starting at the top of her ribs and ending at the top of her pelvis. Her blood and muscles would be infused with a harmless solution that would allow them to become transparent under selective wavelengths of light, including daylight and fluorescent lighting, allowing researchers to easily see through to her internal organs. Her skin in this region would be replaced with a clear, waterproof polymer film; when she wasn’t at the facility, she could wear a flesh-colored silicone panel that would easily snap onto a sternum-mounted fastener. When they showed her the panel plate, she rubbed her hand across its surface carefully, like it was asleep and she didn’t wish to wake it up. “What’s this?” she asked them. It was a small brown nub in the sternum’s center that had been designed to look like a protruding mole. It was the panel’s release button.

The first few months after the surgery, she never released the panel on her own, and on observation days at the facility when the panel was removed, she felt very cold despite the fact that there was no drop in her temperature readings. She began bringing a blanket that she’d put around her shoulders when the panel came off. She avoided looking down at her own organs when the panel was off, mindful to keep her posture straight and her head directed forward or looking up at the ceiling. In order to do this, she pretended she was standing on the ledge of a very tall building, because she was very afraid of heights. Dropping her eyes would not provide a welcome view.

But gradually, this changed. The panel didn’t feel like her own skin so much as a bodice or a giant waistband; she always wore the panel beneath her clothes in public, but when she got home she found she liked removing it and walking around her house in an open robe. The panel wasn’t capable of sweating, but it often felt that way—despite being dry and even slightly cold to the touch, it felt like a tight shirt that was collecting her body’s warm moisture; when she snapped it off and set it on her nightstand, always balancing it upright on its edge against a reading lamp, she swore her organs felt a pleasant rush of air. This wasn’t possible, of course; the plastic layer that coated them wasn’t porous or permeable. But the psychological feeling was a pleasant one that she enjoyed. At first she only caught sight of her organs in accidental peripheral glances—the mirror, the reflective surface of the new chrome kitchen appliances she’d bought with her new salary. Then, day by day, the coils and twines of her insides became familiar geography with patterns and symmetry that didn’t threaten her sense of order but instead increased it.

The only sight that continued to give her discomfort was her beating heart. Not its image but its constant movement when she was at rest. Its pulsing reminded her of the way a digital alarm clock’s numbers would flash repeatedly when the power went out and made her feel like an essential part of her needed be reset. During each session at the research facility, a therapist came into the room at some point and spoke with her and sometimes Cora would talk about the sight of her beating heart with the therapist. Usually the therapist had her speak directly to her heart, saying affirming sentences such as, “Heart, I appreciate you keeping me alive. Heart, I am grateful for your service.” Other times, the therapist asked her to report any unpleasant dreams. Early on, she had a dream that she was at the beach in a bikini, and upon seeing her internal organs a flock of gulls swarmed around her and tried to peck them out. Later she had a dream where she thought she’d woken up only to find herself standing at the foot of her bed watching herself sleeping. Her dreams were being projected on the skin panel resting on her nightstand, playing upon it like a video. It was the dream where seagulls attacked her at the beach.

Recently the therapist asked Cora to consider starting to date again. Cora replied that she’d never enjoyed dating, but that prior to the operation, it had been her habit to seek out companions for one-night sexual encounters. That she’d done this a few times a year prior to the operation, but had not done it since. “Then try finding someone and having sex,” the therapist said.

So she joined an online service and tried. The first man declined to meet after hearing about the operation she’d had. The next said it was okay but changed his mind when she took her shirt off and he ran his fingers along the edges of the panel’s thin seams. “I work on computers all day,” he explained, taking their cases off. Sometimes I get repair calls because the cases come loose and fall off on accident, all on their own.” She assured him that it wouldn’t, declining to admit this was possible if he pressed the release mole firmly enough on accident, or if she pressed it firmly enough on purpose. The third was fine with the operation and the panel’s seams and even asked her to take the panel off and leave the bedroom light on. He wanted to watch her organs during intercourse.

They began having sex, but soon he stopped. “Sorry,” he explained. “I feel like I’m watching a surgery in progress or something,” he said. Cora was annoyed but thought it was better to pretend to be confused. She got ready to say, “There’s no surgery,” or tell him she’d had the operation over a year ago, except she got distracted by her dresser’s mirror. She watched her heart beating again and again like an unanswered question, like a phone in her chest that would not stop ringing. “Hello?” Cora said. In the mirror’s reflection, she could see that the man was no longer next to her in bed. Maybe he’d gone to the bathroom, or maybe he’d quietly left.

“The Transparency Project” will be forthcoming in the Watchlist anthology, due out in April from OR books.