By Aditi Sriram

For centuries Al-Mutanabbi Street in Baghdad was home to bookstores and booksellers, a haven for poets and professors, tourists and traders, picky readers and pickpockets alike. Seven years ago this week, it was destroyed in a car bomb. To most Americans this was just another bombing on just another street in Iraq, but not to Beau Beausoleil. A poet, bookseller and former soldier living in San Francisco, he could feel the heat and debris from Al-Mutanabbi Street invading his kitchen. “My bookstore would have been on that street,” he thought. “That forced distance between myself and the Iraqi people dropped away. I was no different from any Iraqi in that situation.”

Beausoleil’s personal reaction has grown into a global artistic and literary coalition called “Al-Mutanabbi Street Starts Here.” Say it out loud and you will hear the coalition’s mission: to recreate Al-Mutanabbi Street all over the world and continue its legacy as a bastion of literature, culture, and exchange. Beausoleil’s inspiration and guidance have led poets, authors, artists, designers and others all over the world to create artists’ books that contain and cherish the creativity, energy and immortality of Al-Mutanabbi Street. Locals harness their memories, poets apply the printed word, and artists sculpt these oral images into tangible creations that bear witness to not just the loss on Al-Mutanabbi Street, but its revival in the years since.

These readings bring together the original storymongers and producers of paper who met on Al-Mutanabbi Street back when it was a part of the Silk Road trading routes of single-digit centuries.

Every March 5th since 2007, more and more memorial readings have sprung up in the US, and this week, readings have taken place in 14 American cities, 5 cities in the UK, and 2 cities in Canada. Breaking into new geography, the American University of Cairo launched an exhibit of artists’ books this March 5th as well. These readings bring together the disparates who, in their distinctness, make up a literary community: writers and readers, editors and distributers, translators and publishers, critics and artists, not to mention the original storymongers and producers of paper who met on Al-Mutanabbi Street back when it was a part of the Silk Road trading routes of single-digit centuries.

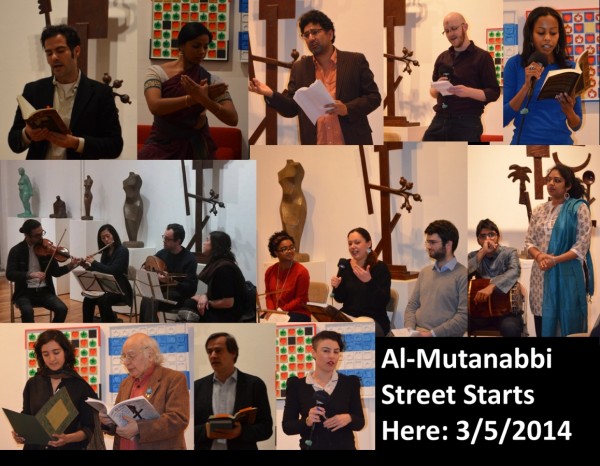

Two days ago, those same disparates gathered in an art gallery in SoHo, to remember Al-Mutanabbi Street and revive it on the cobblestones outside 137 Greene Street. Oded Halahmy and his Foundation for the Arts generously hosted a reading at Oded’s own Pomegranate Gallery, which exhibits contemporary Iraqi art and showcases original artistic expressions in Middle Eastern literature, poetry, art, dance, music and film. The lineup was spectacular. Oded began the evening with personal recollections of Al-Mutanabbi Street, having grown up in Baghdad and been there countless times to buy books while his father whiled away the time drinking coffee and eating dates at Shahbandar Café. He read two original poems in Arabic, about Al-Mutanabbi street, and the consummate singer Oum Kalthoum, and the laughter started with the Arabic-speaking audience and rippled outward to the English-speaking audience whose appreciation came one translated line later. Dena Al-Adeeb, a writer and artist whose family fled Iraq just before the Iraq/Iran War in 1980, shared personal accounts through a video presentation called “Disturbance” which “functions as a cartographic device, charting the interconnections between three pivotal moments in contemporary Iraqi history and their relationship to a trilogy of personal and collective displacements.”

Aaron Hollander, a doctoral student of comparative religion, noted that it was also Ash Wednesday, a day of mourning and repentance to God, and read from his original poem, “Repentance” which opened with ashes:

and closed with ink:

Fatin Abbas, from Sudan, read from the anthology that Beausoleil co-edited and PM Press published, Al-Mutanabbi Street Starts Here: Poets and Writers Respond to the March 5th, 2007, Bombing of Baghdad’s “Street of the Booksellers”. She chose carefully an essay by Yassin “The Narcicyst” Alsalman, an Iraqi-Canadian journalist and Hip Hop MC who lives in Montreal. “Al-Mutanabbi Street was his red light district slowly eyeing the wisdom that was into the knowledge that be, now,” Alsalman’s narrator says in “Dead Trees” about a close friend diagnosed with lung cancer and watching Baghdad, too, choking on “flames of hell.” Alsalman’s narrator continues:

Metaphors echoed around the art gallery, dancing in the shadows of the sculptures and peeking out of the pages of the anthologies that stand upright on glass cases not unlike the art work. For Beausoleil as well, there was no turning the page on Al-Mutanabbi Street in particular, and the Iraqis at large. Approaching March 5th this year, he said, “I want people to see the commonality between any Iraqi artist and any artist here, any cultural institution in Iraq and any cultural institution here. That we all stand on the same street together, a street that happens to be called Al-Mutanabbi. What we are doing is expanding the whole idea of Al-Mutanabbi Street to cultural streets around the world, and to cultural workers around the world.”

Seven years ago a bomb changed a city’s topography and scattered its literature like debris over the rest of the world.

Rym Bettaieb, an Arabic Professor at Columbia University, agreed. The evening began with a group of strangers in a gallery, she said. But the poetry, music and dance that followed, including the poems she read by Early Arab Sufi Women, and the poems her Arabic students had chosen, practiced and performed, unified the group. We are leaving with a shared sense of everyone’s pain and problems, she said, with a smile on her face. This evening has brought us together. Similarly Roger Sedarat rejoiced in his oblivion—“The music was so good I forgot my own name”—before reading his piece in the anthology, “Abridged Qasida for Al-Mutanabbi Street.” Indeed, the instruments and voices of musicians Shelley Thomas, Samer Ali, Nobuko Miyazaki, Brian Prunka, Dafer, Roopa Mahadevan and Sriram Raman carried into the high ceilings of the gallery and mesmerized everyone. The South Indian classical interpretation of Sam Hammod’s poem “The Grief of Birds” that featured bharatanatyam dancer Sahasra Sambamoorthy was a flutter of footwork that remembered the footsteps on Al-Mutanabbi Street: playful, unhurried, eager, to-be-caffeinated at Shahbandar Café.

Ulrich Baer, Vice Provost at NYU concluded the evening by reading from a collection he edited, 110 Stories: New York Writes after September 11. “I really believe in the power of such books to keep memory alive, and also to move people forward in a world that continually has people blowing up the possibility of dialogue and exchange,” he reflected afterward, unwittingly paraphrasing the Preface to the Al-Mutanabbi anthology by literary critic and scholar Muhsin al-Musawi, who wrote, “Al-Mutanabbi Street…challenges our knowledge of the genealogy of culture and the resilience of an industry that has been resisting destruction.”

Seven years ago a bomb changed a city’s topography and scattered its literature like debris over the rest of the world. Seven years later, 75 strangers laid a foundation of words, art, music and dance on the hardwood floors of Pomegranate Gallery in SoHo, in response: Al-Mutanabbi Street starts here.

Aditi Sriram is a writer and editor. She first wrote about Al-Mutanabbi Street for Narrative.ly; the full article, which includes an interview with Beau Beausoleil and photos of the artists’ books, is here. She would like to thank Beau Beausoleil, the Oded Halahmy Foundation for the Arts, and Sukhdev Sandhu for helping put together the New York City memorial reading on March 5, 2014.