By Abigail Rasminsky

Those of us who were admitted to the seminar were lucky, and we knew it. At the first meeting on a late March afternoon in 2010, thirty writing students crammed around a rectangular table or sat against the walls, notebooks on laps, and waited, uncharacteristically quiet, for Dr. Sacks to begin.

“The Case History,” a four-week literature seminar, was one of Oliver Sacks’ first forays into teaching writing students at the Columbia University School of the Arts, a dozen subway stops downtown from the medical school, where he had been holding court for years. In preparation we’d read A.R. Luria’s <target=“new”>The Man With a Shattered World. At the time, Dr. Sacks was 77 years old and already had trouble sitting and seeing. Back pain caused him to perch on the edge of a desk, and he apologized for the face blindness that prevented him from recognizing our eager expressions from one session to the next.

On that first day, we went around the table and introduced ourselves, which essentially meant divulging what we were writing about. His interest—or lack thereof—in our chosen subjects was obvious. My project was a book about the back injury that had ended my career as a professional dancer, the fallout from living with chronic pain, and the unusual journey I went on to heal my body. Dr. Sacks’ work, as well as that of his colleagues at The New Yorker—Atul Gawande and Jerome Groopman in particular—was a staple in my library, the pages heavily annotated. These books were my literary guides, teaching me, case by case, how to write a medical narrative, reminding me that these stories of our fragile, miraculous bodies were worth telling, and could be written with great beauty and pathos and little self-pity. To say that I was pleased when he perked up at my subject is a gross understatement—I was lit up from the inside for the rest of the day.

As promised, Dr. Sacks didn’t remember any of our names or faces, but over the course of the seminar, he never forgot my subject.

“Who’s the one who writes about pain?” he’d say, gazing around the room.

“Over here!” I’d wave my arm, as we’d learned to do.

“Ah! What do you think of Luria’s narrative?” To be writing something of interest to him was purely luck of the draw, and I tried my best to answer his questions, thrilled and terrified by his attention.

We were just thrilled to be there, learning from the man who had opened up a new literary world with his patients’ struggles.

Our discussions of the assigned reading often meandered, and we sometimes found ourselves steering the conversation while Dr. Sacks listened. But none of us cared exactly what shape the two hours took—we were just thrilled to be there, learning from the man who had opened up a new literary world with his patients’ struggles, a person who, even at his age, was still eager to try new things.

The mood in the room on the last day was slightly melancholy. Toward the end of the session, Dr. Sacks peered out the window onto Columbia’s campus and took one of his signature pauses. We waited, no longer alarmed by the extended silence. Finally, he turned to us and declared with genuine glee in his voice—a glee that made us all erupt with laughter—“I think you all have taught me more than I’ve taught you!”

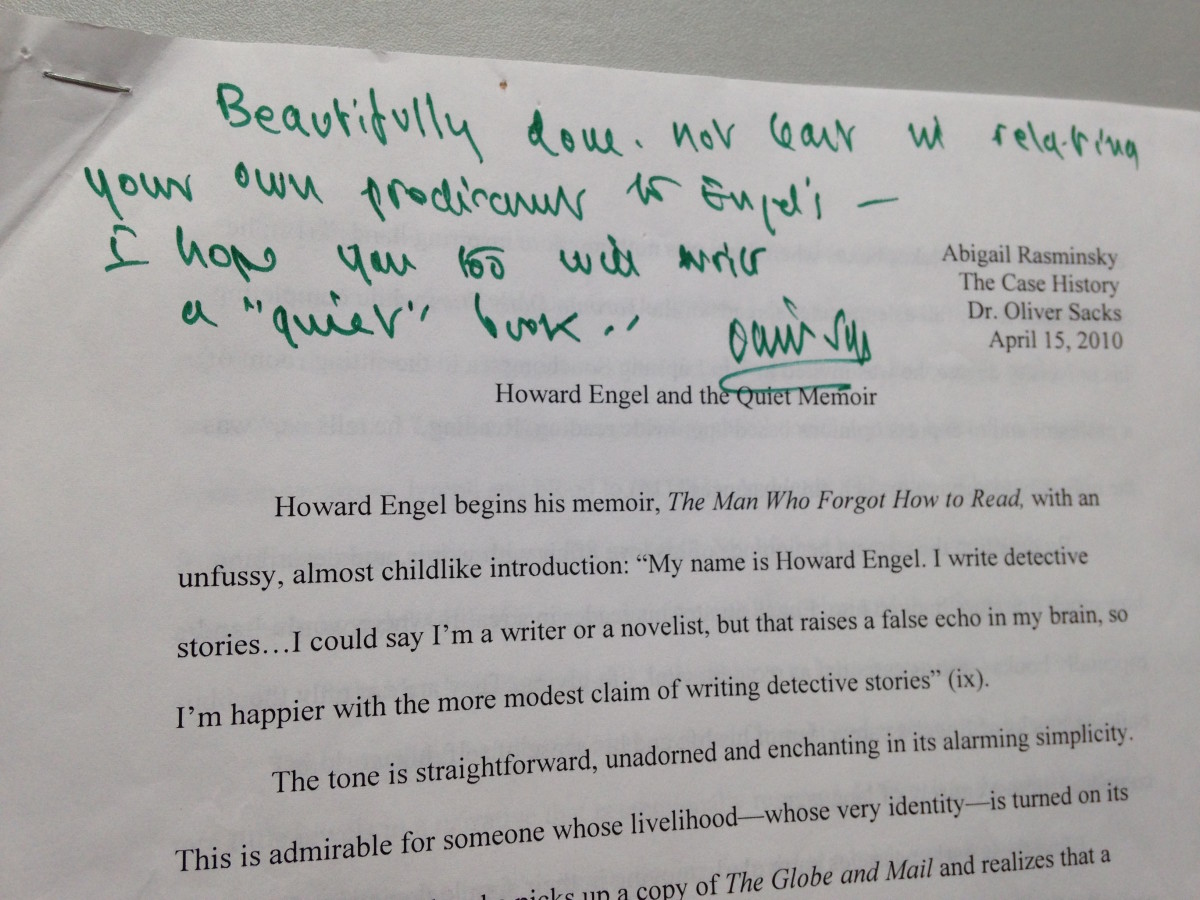

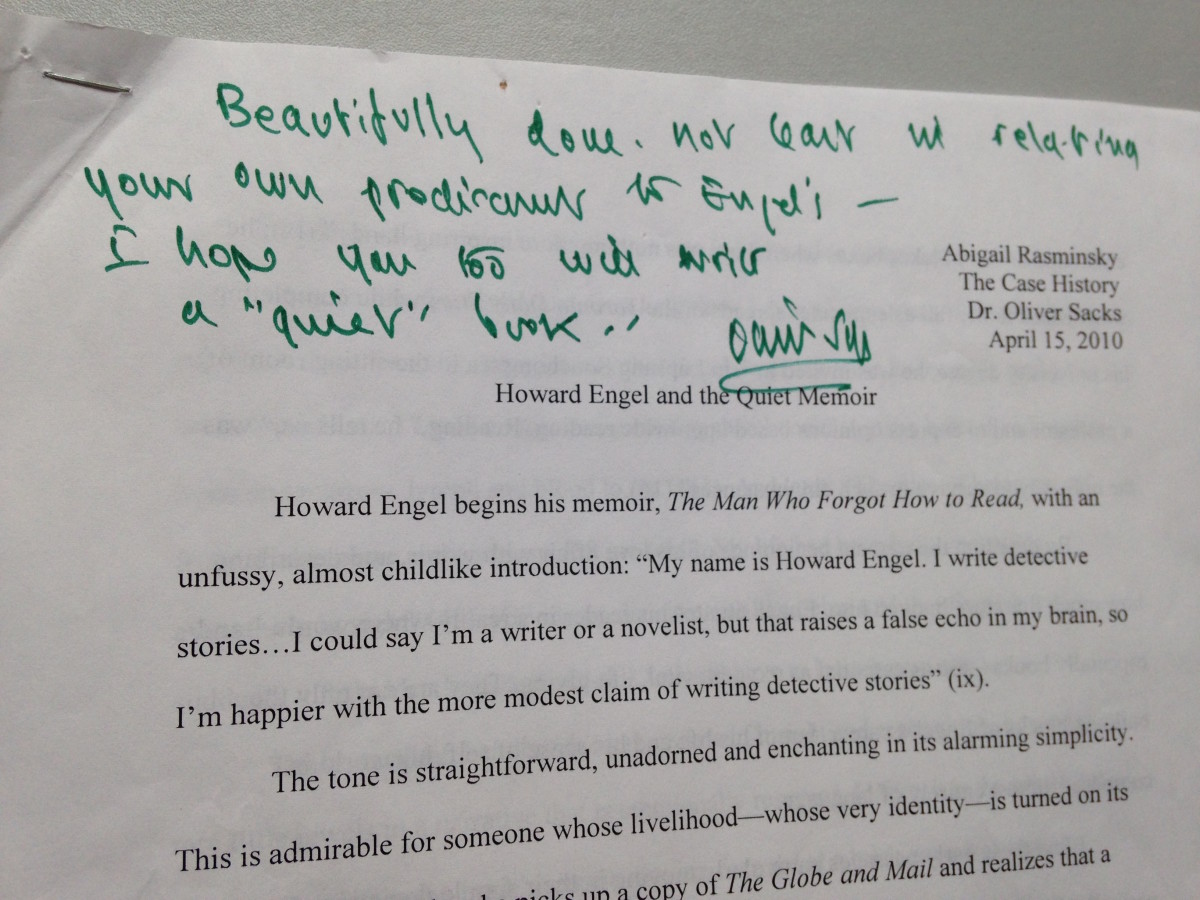

At the top of my essay, Dr. Sacks had scrawled, “I hope you too will write a ‘quiet’ book.”

The other day, after hearing of his passing at age 82, I searched through my files for the paper I wrote for his class—a short analysis of Howard Engel’s <target=“new”>The Man Who Forgot How to Read. Engel was both a writer and the subject of one of Sacks’ essays, a work-in-progress he’d shared with us in class called “A Man of Letters,” later published in The New Yorker. As the title suggests, the book is about a writer who, after suffering from a condition called alexia sine agraphia, must reconstruct his life without being able to read. It is not a redemptive memoir. It is instead a quiet story about one man painstakingly reassembling his reality after an illness that affected the very essence of his self-conception. Although my back injury paled beside Engel’s disability, I made a short reference in the paper to how I had had to rebuild my life after my injury deprived me of the very thing I loved most, the thing on which I’d hooked my own identity—the ability to dance.

At the top of my essay, Dr. Sacks had scrawled, “I hope you too will write a ‘quiet’ book.”

For years, while I struggled to get that book on paper (as I still do), I kept the essay pinned to the cork board above my desk simply to look at Dr. Sacks’ comments—a few words jotted in haste that still remind me, as his work has done for so long, to ignore the odds, and keep going.