When I arrived in New York City after college, I moved into a tiny, one-bedroom apartment at Seventeenth Street and Third Avenue. It had a fire escape that was perfect for the burglar who climbed up it a few months later. Since I worked at Esquire then, uptown on Madison Avenue, I described my new home to friends as a cozy, downtown abode, walking distance from Greenwich Village.

It took me several years and several moves to discover that downtown was an elusive word, whose meaning depended on whom you talked to, and where you lived. My home on Seventeenth Street was followed by one on Pearl Street with a view of the Brooklyn Bridge and followed later by a loft in a Centennial building in SoHo, where three massive front windows gave me a view of the cast-iron buildings across the street.

Whatever my geographic location, I discovered that there was a common thread, a unifying sensibility, running through downtown neighborhoods. They were all a little messy, a little irregular, breaking off from the mainstream–cranky, creative, and, inevitably, controversial.

I had researched SoHo’s history for my book Illegal Living: 80 Wooster Street and the Evolution of SoHo and knew that there was a sprinkling of artists living in rented SoHo lofts by the 1950s. Artists were moving in because of the availability of large, cheap spaces that could accommodate the large works that they were making. Once SoHo became known as an artists’ neighborhood, the galleries followed, also attracted to the large spaces and cheap rents.

But well before SoHo, there was a vibrant art scene elsewhere downtown: pioneering cooperative spaces on or near East Tenth Street between Third and Fourth Avenues as well as other artist-run venues in Greenwich Village and lower Manhattan. Fourteen of these experimental and innovative spaces are the focus of guest curator Melissa Rachleff’s new exhibit at the Grey Art Gallery NYU, Inventing Downtown: Artist-Run Galleries in New York City, 1952–1965. A clinical associate professor at New York University’s Steinhardt School of Art, Rachleff spent six years researching the subject, interviewing artists and gallerists, and gathering the nearly 230 objects in the show.

Largely excluded from showing their work in the commercial galleries uptown on Fifty-Seventh Street, where Abstract Expressionism dominated, downtown artists, many of whom lived nearby, networked and improvised, conspiring in coffee shops and in their studios, where rents were cheap. Following in the tradition of The Club (1948–1962), an organization on East Eighth Street, where lectures and panel discussions openly aired the debate between figuration and abstraction, and inspired by The Club’s renegade members who organized The Ninth Street Show (1951), an exhibit that shook up the establishment, downtown artists developed bylaws and launched their own spaces. “While they were opposed to the idea of art as commodity, and disdainful of Pop Art,” said Rachleff, “most of the artists would have loved to make a living off of their art work.”

The Tanager Gallery (1952–1962) at 51 East Fourth Street, one of the earliest of the new spaces, was founded by five Americans—Sculptor Williiam “Bill” King (1925–2015) and painters Lois Dodd (b. 1927), Angelo Ippolito (1922–2001), Charles Cajori (1913–2013), and Fred Mitchell (1923–2013). Within a short time, several new members joined, including Philip Pearlstein (b. 1924) and Alex Katz (b. 1927). Artists paid dues of ten dollars per month and gallery members frequently made studio visits scouting for new artists.

Ippolito was the major force behind the Tanager, handling everything from painting the walls white to installing exhibits and designing invitations. Shows featured works of both known and unknown artists and were titled only with artists’ names. The gallery offered, writes Melissa Rachleff in the fine catalog accompanying the Grey exhibit, a “nuanced mix of representational and abstract art that came to characterize the 10th Street scene.” During its decade-long existence, the Tanager organized over a hundred shows in New York. Its aspirations, however, were grander, since the gallery bylaws included plans for shows to travel internationally.

Partially in response to an exhibition at the Jewish Museum, Artists of the New York School: Second Generation (1957), organized by Meyer Schapiro, which included twenty-three artists, not one of them affiliated with the Tanager, gallery members at the Tanager spent five years developing what they envisioned as their own New York project, a series of five two-week exhibitions organized around five themes: Old Masters, nature departed, natured observed, paint, and personal mythology. Eighty-five artists were invited to participate in the fall 1958 exhibits, which were to be accompanied by a book with international distribution. Unfortunately, the project was doomed to failure when painter Elaine de Kooning was left out of the invited group and Willem de Kooning refused to participate. The book project and the exhibits fell apart.

On view in the Grey gallery are several works from the Tanager’s landmark exhibit, The Private Myth (October 1961), organized by Sidney Geist and Philip Pearlstein, which focused on the role of the artist as a mythmaker. Prominent among them is Pearlstein’s Roman Ruin (1961), an oil-on-canvas close-up of a ruin, painted in a pastel palette that gives the work a dream-like quality. Also on display are powerful works by Sidney Geist, Studded Figure (1957), a painted wooden piece; Mary Frank’s Reclining Figure (1960); and Alex Katz’s Ada Ada (1959), a double image of his muse, his wife Ada.

Established the same year as the Tanager, the Hansa Gallery (1952–1959) shifted its location from East Twelfth Street to Central Park South before it closed in June of 1959. It was founded by twelve artists, many of whom had studied with Hans Hofmann in New York and Provincetown and were influenced by what Allan Kaprow viewed as Hofmann’s Hegelian thinking—a dialectical approach in “its search for dynamism rendered in two dimensions.”

The push-pull philosophy often resulted in arguments among members—including such artists as Jan Muller, Wolf Kahn, Richard Stankiewicz, Barbara Forst, Jean Follett, Allan Kaprow, and Jane Wilson. Gallery membership changed frequently as artists found dealers uptown and left. Kaprow brought in George Segal (1924–2000) and Robert Whitman (b. 1935) in 1956 and 1958, as well as Lucas Samaras (b. 1936) who joined the gallery’s exhibitions in their final season.

On display at the Grey is a draft of page five of the Hansa’s bylaws from 1951, where an entire paragraph delineates the duties of the gallery’s treasurer, who was to keep all accounts and bank accounts, determine the amount of and collect dues, handle sales commissions and other charges, issue receipts, and write and present to the membership a summary of the gallery’s annual accounting. Elsewhere in their bylaws, the Hansa stipulated that artists should produce artwork worthy of exhibition, “to guarantee that the group membership shall be of active and productive artists and not of ‘riders’ whose principal motive for joining the group might be social.”

The focus was on younger artists, who initially paid fees of twenty-one dollars monthly, later reduced to fifteen dollars, and who were required to work twice a month in the gallery during business hours. Disputes over installations were not uncommon. Felix Pasilis and Stankiewicz once got into a fistfight after Pasilis sneakily rearranged an installation to give greater prominence to a friend’s work.

Hansa artists’ works represented in the Grey show include Jane Wilson’s Portrait of Jane Freilicher (1957), an oil on canvas merging abstraction with figuration, and Jean Follett’s Many-Headed Creature (1958), a piece that recreates a fragmented body on a wood panel out of junk and found objects–a light switch, socket cooling coils, a window, a screen, nails, a faucet knob, mirror twine, cinders, a caster, springs, and rope.

In March 1958, Kaprow took over the whole gallery with his Untitled Environment, an installation where he hung translucent strips of plastic and rayon from the ceiling. His second project, An Exhibition (November/December 1958), was harshly criticized by New York Times art critic Hilton Kramer, who dismissed its high-powered spotlights and nasty bits of old paint rag tied to straw, as well as its sound, which he “identified mostly as sirens and doorbells.”

Nearby, on East Tenth Street, was another co-op space, the Brata Gallery (October 1957–April 1962) where American artists, including Al Held, Ed Clark, and the painter/sculptor Sal Romano joined with a number of Japanese artists to show works that dealt experimentally with abstraction.

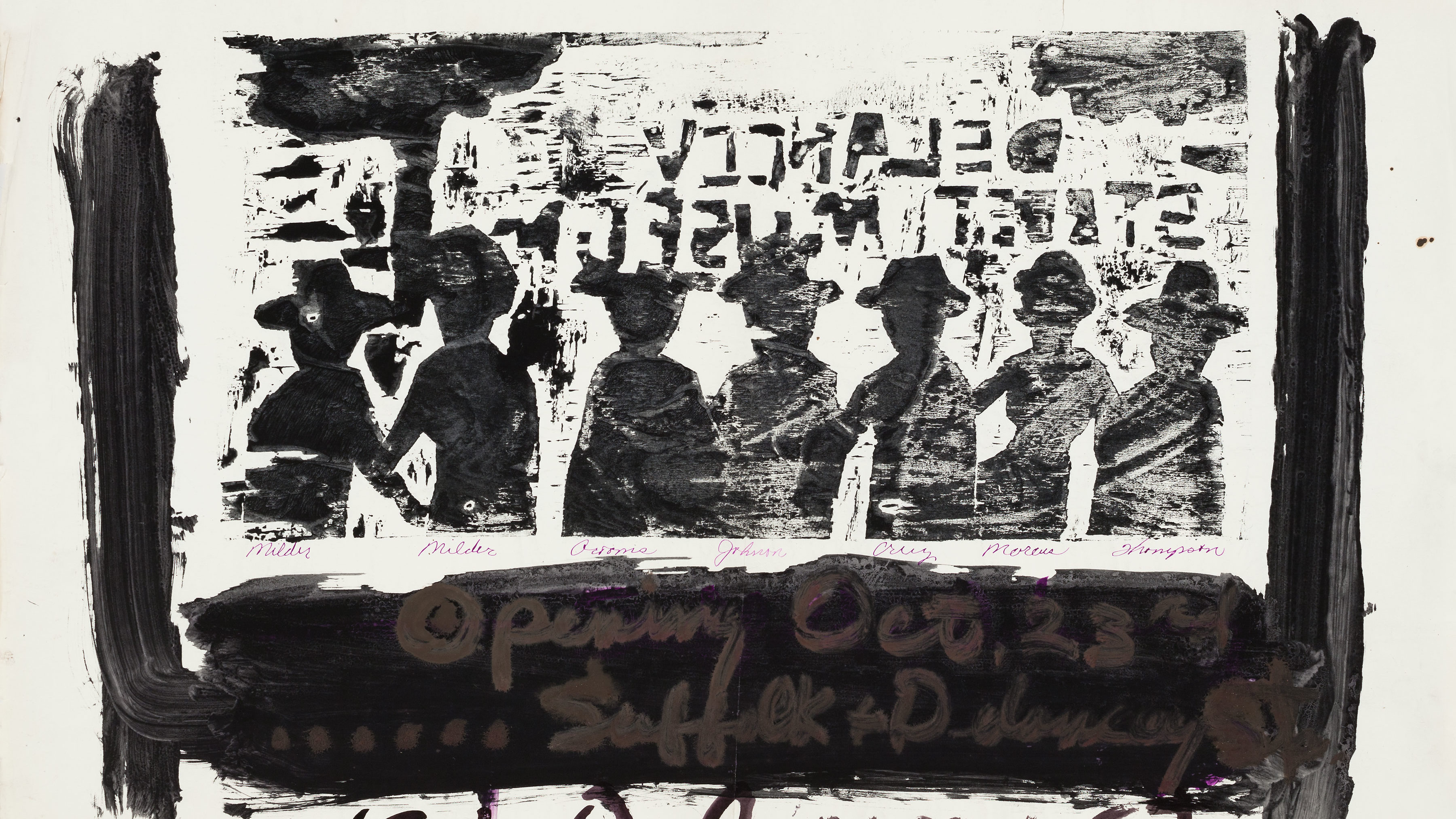

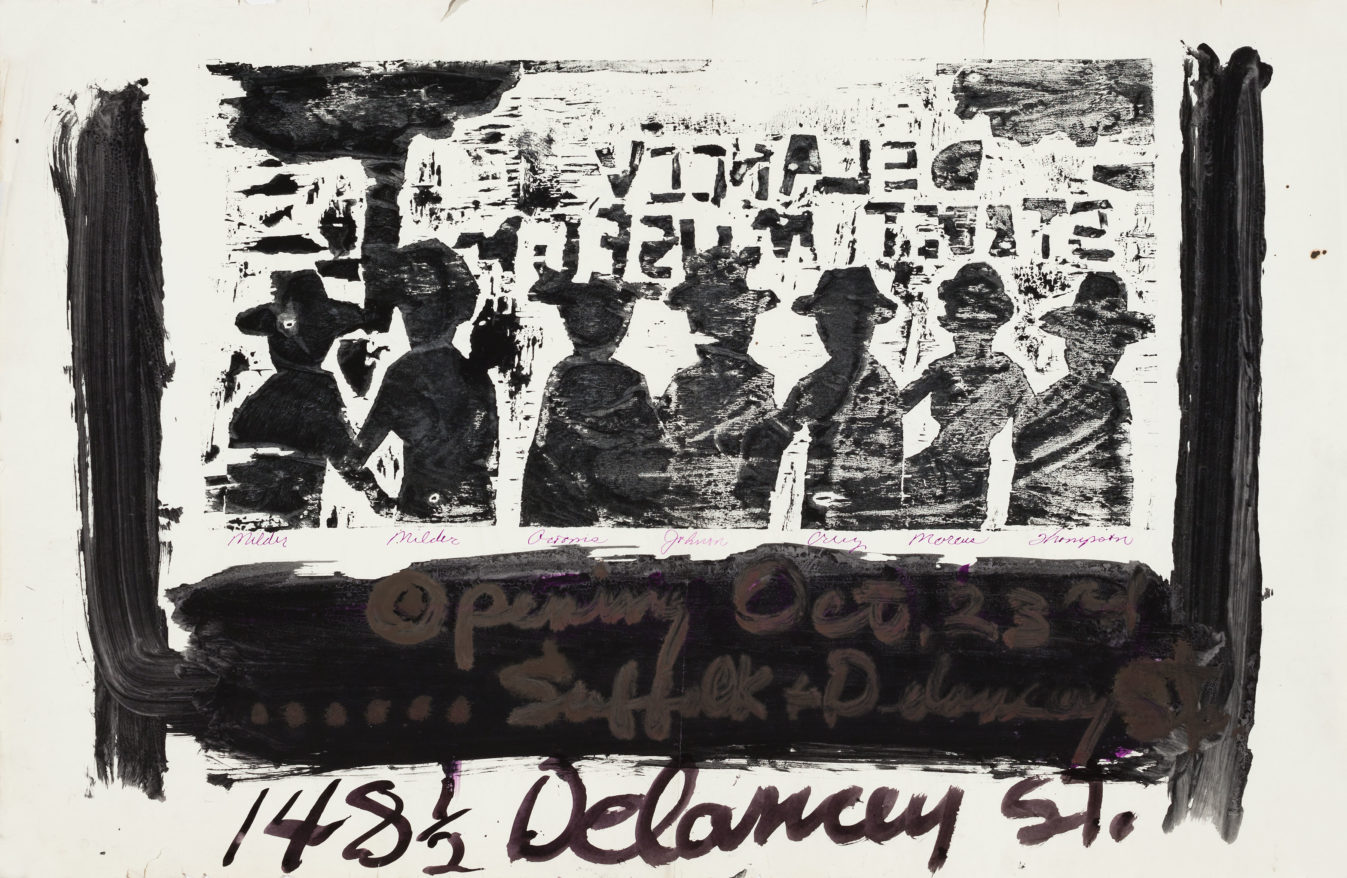

Not all of the downtown galleries were co-ops. City Gallery at 735 Sixth Avenue (November 1958–May 1959), Reuben Gallery at 61 Fourth Avenue (October 1959–June 1960), Delancey Street Museum at 148 Delancey (October 1959–May 1960), and Judson Gallery at 239 Thompson Street (February 1959–January 1962) followed an entirely different model, installing art in venues that often served as combined gallery, studio, and living spaces. All four produced remarkable shows, many with installations or “Happenings.”

Located in front of Red Grooms’s loft, City Gallery drew a big crowd to its group show, Drawings (1958–1959), a huge show, hung salon style, that included the work of Red Grooms, Mimi Grooms, Robert Beauchamp, Michaela Weisselberg (now Mica Nava), Joan Herbst, Jay Milder, Bob Thompson, and Emily Mason. Often seen as a reaction to the art on Tenth Street, it was a lively show, the work of young artists, many in their early twenties. Though short-lived because the building was torn down, City Gallery left its mark as a rebellious, innovative space.

Equally anti-formalistic was the Reuben Gallery, where Allan Kaprow’s 18 Happenings in 6 Parts and Claes Oldenburg’s The Street attracted crowds. Artists here often crossed genres with sculpture, painting, and theater, becoming components of their performance art. Martha Edelheit worked with thick paint and incorporated found objects like license plates into her powerful “extension paintings.” Yvonne Rainer and Robert Morris, dressed in bathing suits, performed Simone Forti’s See Saw on a homemade beam. Experimental and physical art were being moved in new directions.

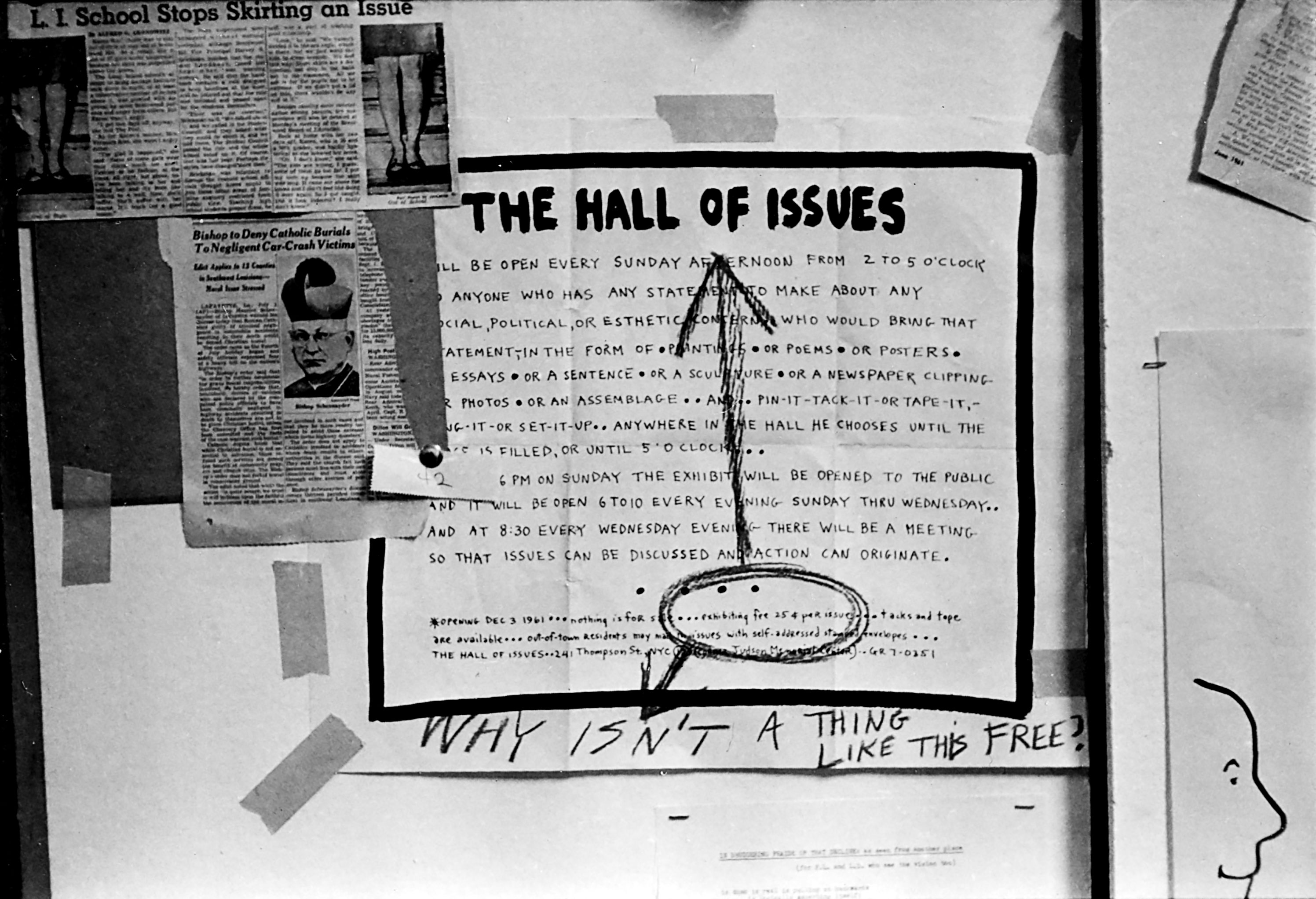

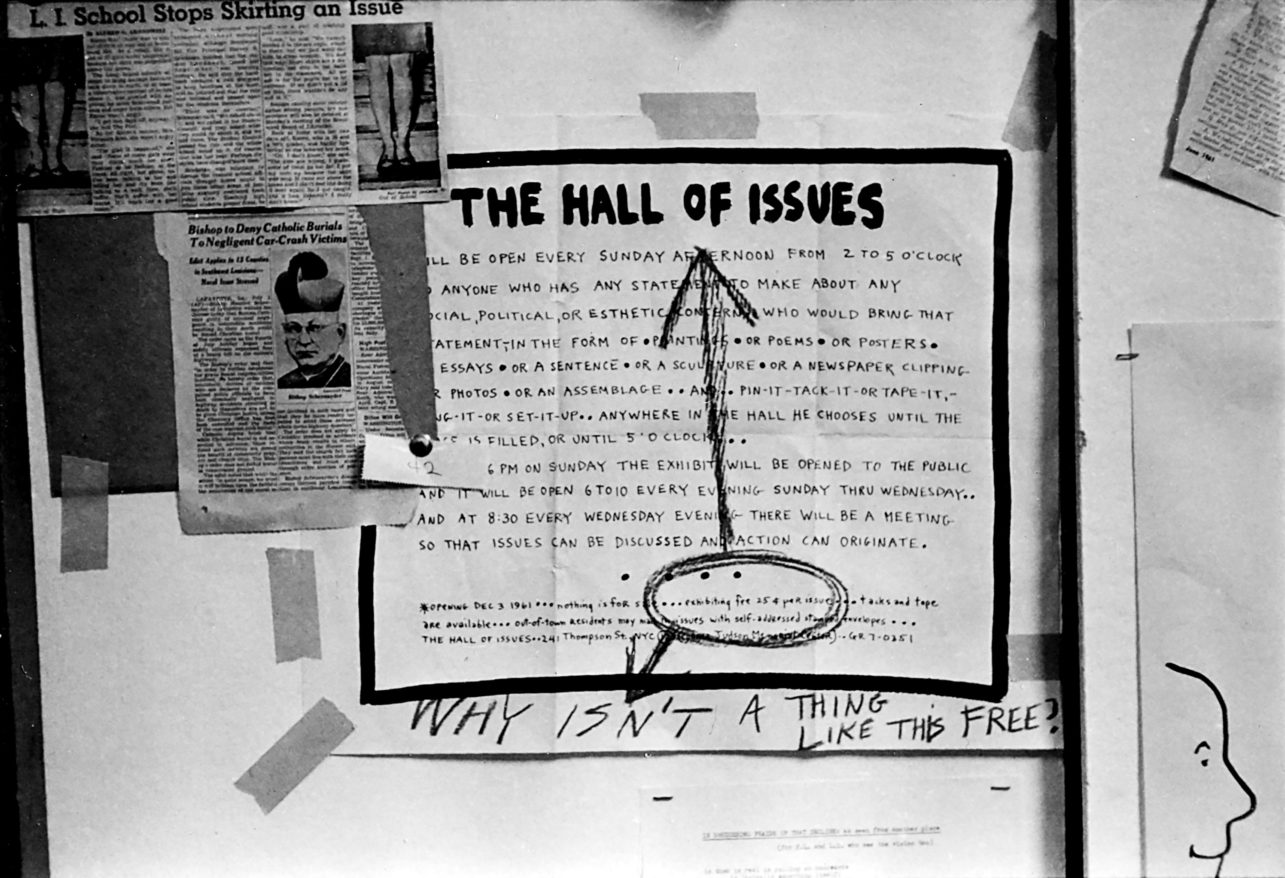

The push toward performance could be seen elsewhere downtown in the early 1960s. Certainly at 112 Chambers, Yoko Ono’s fourth floor loft, and at 79 Park Place, located further downtown on Washington Street. Evident, too, was the move in the direction of politics that followed the election of John F. Kennedy as president in 1960. At The March Group at 90 East Tenth Street (1960–1962), the Hall of Issues at Judson Memorial Church at 55 Washington Square South (December 1961–January 1963), The Center (1962–1965), and Spiral Group at 147 Christopher Street (1963–1965), artists expressed their social activism, whether the subject was the Cold War, the New Left, the fight against poverty, or the protest against racial discrimination. Launched in Romare Bearden’s loft on Canal Street, fifteen African American artists including Charles Alton, Hale Woodruff, Norman Lewis, and Emma Amos formed the Spiral Group and began their debate on art and race. “It took them two years,” writes Melissa Rachleff, “to reach the consensus that made it possible to mount Spiral: Works in Black and White in 1965, their only exhibition.”

Only one uptown gallery is included in the Inventing Downtown exhibition, the Green Gallery at 15 West Fifty-Seventh Street (October 1960–June 1965). Financed by the collector Robert Scull, the gallery drew on the expertise of its director, Richard Bellamy, who had previously worked at the Hansa Gallery. Showing the diverse work of Mark di Suvero, Tadaaki Kuwayama, Joan Jacobs, Pat Passlof, James Rosenquist, George Segal, Tom Wesselmann, and Claes Oldenburg, the Green Gallery successfully brought downtown art uptown.

But not before the downtown aesthetic, embedded here and there in co-op galleries and other short-lived experimental spaces, altered the artistic landscape, paving the way for a pluralistic arts community and for alternative spaces that survive today. Although booming real-estate prices resulted in most of the downtown galleries moving to Chelsea, some arts organizations persist, including The SoHo Arts Network, a consortium of nonprofit spaces, Apex Art, More Art, and the Gross Foundation.

Rachleff hopes that people will see the exhibition in and of itself, not merely correlating it “to the concerns of right now.” It was exciting for her to think about the period in a new way, “through the institutions artists established instead of the formal art historical lineage.”

The goal was to study the variety “of visual strategies that co-existed” in an effort to see the era more broadly. “Put another way,” Rachleff said, “this is what New York’s downtown art scene looked like at mid-century when women artists and nonwhite artists were included.”

Inventing Downtown: Artist-Run Galleries in New York City, 1952–1965

Grey Art Gallery NYU, January 10–April 1, 2017

Inventing Downtown: Artist-Run Galleries in New York City, 1952–1965, comprehensive catalog published in conjunction with the exhibit by Melissa Rachleff, with an introduction by Lynn Gumpert, Director of the Grey Art Gallery.