By Cormac James

By Cormac James

Brought to you by the Guernica/PEN Flash Series

I don’t know what exactly it is, but I have something in my ear. I think of it as some kind of scab, and know well it’s not. The idea of a scab must be reassuring, I suppose. Preferable, apparently, to whatever it serves to conceal. If the thing were almost anywhere else, I could just look and see what it was. Perhaps I’m glad I cannot, but why then does the prospect of knowing what it is feel so much like the prospect of relief? Because now it’s started to nag at me, not knowing what exactly I have in my ear, almost more than the thing itself. I wouldn’t have thought that possible, physically, but it is.

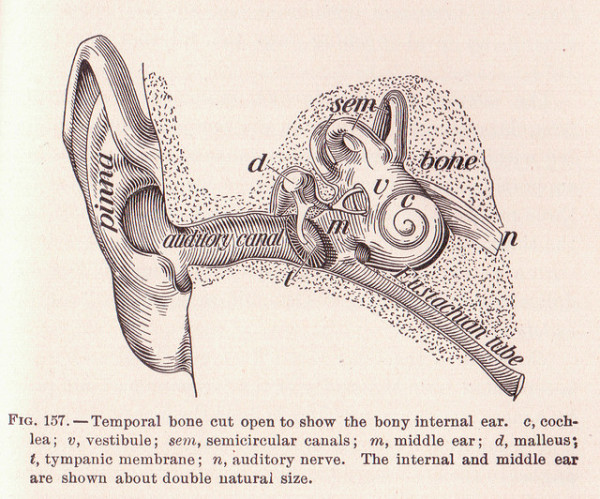

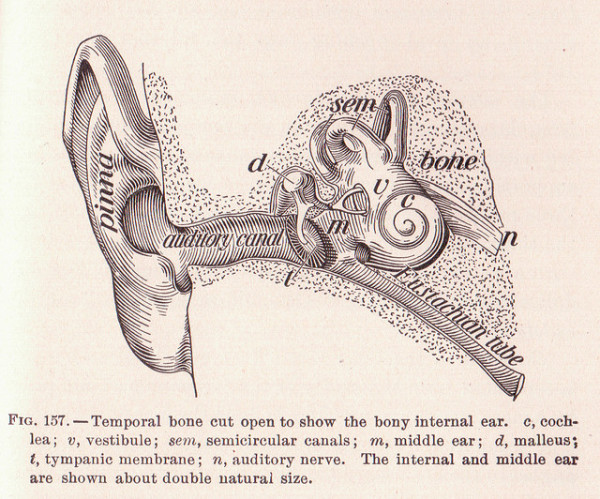

As I say, almost anywhere else on me, I could just turn my head and look. But it’s not anywhere else. It’s exactly where it is. I’ve tried mirrors, but mirrors are not as simple as you think. It’s not just about getting your eye in line. You need light, shone down into the depths, but to see what it shows you need your eye in precisely the same spot. So, you can have light or a line of sight, but you can’t have both. And even if you could have both you’d need not one mirror but two, to bring your eye from the front of your face into the hole in the side of your head.

I’ve tried taking pictures, of course, with my phone, but any distance at all is too far, and holding the phone closer blocks the light, and forced flash gets you an image that’s grainy and blurred, which could be a close-up of almost anything at all, from an arsehole to an x-ray to the mouth of a conch.

I don’t know how many times in the day the finger goes in for a little dig. I know I shouldn’t, but can’t seem to help myself. That old line. I know well it’s about the worst thing I could do. So much traffic gives the thing no honest chance to heal. Then it leaves me—or I leave it—alone for a day or two, and my mind starts bragging about a miracle cure. The wise man in me knows better, but he’s no match for hope, and hope sends me digging again, to prove myself wrong or to prove myself right.

Every now and then, for my troubles, I get a little reward. If I haven’t gone in for a day or two or three, my finger suddenly brings something out. Some kind of flake or crust. It’s never as dark or thick or meat as an actual scab. Certainly nothing looks like it ever was part of me, something I’ve lost, more like something I’ve stumbled on and unearthed, that I get to keep. I put it with my collection, in the box.

I keep thinking, if only I could get it off in one clean stroke. I can see it happening, like a price sticker peeled from the cover of a book. You work your nail in under the edge, and start to pluck. Underneath, afterwards, I see the skin newborn. Because that scab isn’t something my skin has grown. It’s not an outburst or a flaw. We’re separate, it and I. A wet leaf and a concrete path. I peel it off and the surface beneath is pristine, the way it’s meant to be.

When I was two and three, I had a lot of wax coming out of them both. I say a lot. I mean a slow, steady flow. Thinking of it, I hear them saying clean your ears, and I hear them saying leave your ears alone. With something very like the voice I call on constantly nowadays, to berate myself. It built up, and deep down it went hard, and I think for a while that boy was clinically or at least practically deaf.

I like the thought of it—that condition, that boy—even if I don’t quite know why. So dig. Very likely something about being beyond reach. A fantasy, I know. I’m jealous nonetheless. I see him on the floor, on his knees, face strangely close to the ground, like someone who’s lost a contact lens. Pitched forward, jug-like, pouring the whole of himself into his toy, which is not his toy but his whole world, the visible part. Now the hands are gesturing, to mimic the gestures he sees inside his head. That’s his world, and those are its laws, tailor-made.

The woman standing behind him calls his name. He doesn’t answer. But it’s a familiar silence, which she thinks she understands, because of how old he is, and how wrapped up he’s always been in himself. She calls a second time, louder, and still gets no response. Her voice isn’t yet brutal enough to ruin his game. His game isn’t yet shrewd enough to work in the alien sound. But now a bigger bulk comes to stand in the doorway. The man has heard and come from the kitchen, hoping and fearing it’s his own name she’s called. She calls once more, then it’s the man’s voice that seamlessly takes up the task, louder than anything the room has heard so far. There’s more in it than volume. Now there’s a future too. Now the man is gesturing grandly. With the sound turned down, the scene looks of his own making entirely. He’s working himself up. He’s been biding his time and now’s his chance, and no matter how—if ever—the boy answers, it will be too little too late. He’s too ripe. He hears in the silence an accusation he cannot answer, and cannot stand.

How long before the boy feels something or someone behind his back? I myself often do. It’s me the man’s shouting at, obviously. The liar. The mimic. The mute. Not his son but some other boy, that merely looks like him, whose acting is always an affront, and always a test, which one way or another, sooner or later, he always seems to fail.

With perfect provocation, I still refuse to turn. Why trade my world for the one they’ve relentlessly prepared and preferred for me, hour after hour, day after day? What good could possibly come, now, of turning around? I can’t hear them, but they don’t know that. There’s a whole other life they’ve yet to imagine for me, but which I’m beginning to imagine for myself. They’ve yet to hear the doctor’s cue. Then, of course, they’ll have one wide answer, within easy reach, for almost everything I do. They’ll be too eager to imagine the burden—the thought of the punishment that is their child’s deafness, which they know they deserve. Too soon there’ll be disappointment, when the specialist revises the story. They won’t hear his qualifications the first time round. He’ll have to repeat them, dumbed down. There’s nothing wrong with him that can’t be fixed, fairly easily. The child cannot hear, but is not deaf, he’ll say.

It’s the care that came afterwards I resent, not the neglect that went before. Because I know what’s awaiting that little boy, when a passage is finally—suddenly—opened to the blaring outside. Leave him be, I say. Just a little longer. He’s happier in there.

I keep telling myself I’m merely clearing out a blockage, but wonder if I’m not making it worse. The thing always seems to come back thicker and wider and tougher than before. With time it feels I’m having to dig deeper and deeper into the ear. It’s no longer just collecting at the bottom like sediment or silt, but is now working itself up the sides, like the caulk of a lime-furred pipe. I think of that, and think of a foreign body—wire, splinter, stone—first swaddled then swallowed in growing wood or flesh. If I didn’t keep cleaning relentlessly, layer would build on layer and the open section start to shrivel, and shrivel, until completely closed up. That’s why it feels so urgent, the work.