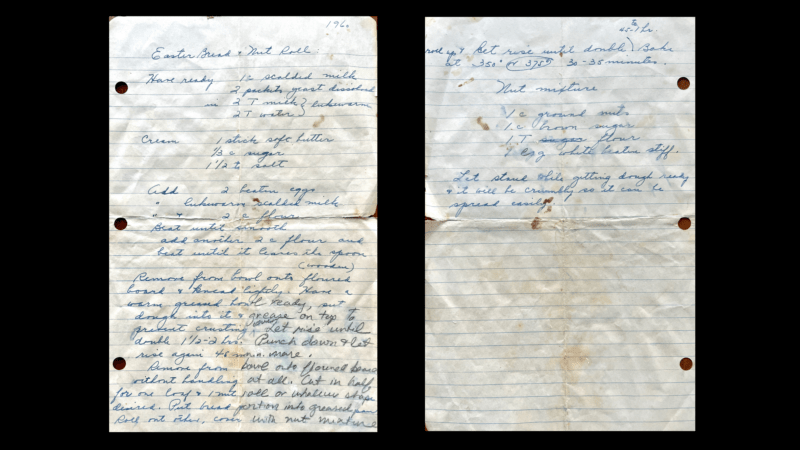

Maybe it’s the recipe’s “lukewarm scalded milk” that spills on the bottom corner of the page. Fountain pen ink swims up to meet it, ghosting the words below. No matter. Mary made her Easter Bread and Nut Roll so many times since she wrote it down in 1960—the date safe and crisp up at the top—that she barely needed to look at the recipe.

1960: the year Mary’s youngest granddaughter was born. That’s me. Sixty years later, in 2020, after finally laying my hands on yeast in the midst of this pitiless pandemic, I turn on the oven to 350 F.

I also grab my reading glasses. Determination and a strong light flush out the ghosts from between the lines. As I begin to pencil in my grandmother’s words, my hand disassociates from my brain, takes on a life long gone. Suddenly my grandma, dead of ovarian cancer at 82 in 1975, is alive again, guiding my hand. It’s odd, so very odd, to follow her cursive characters, elegantly strewn across the lines, all attached to one another. My fingers balk, seek a staccato rhythm, try to break each letter off from its mates. But my grandmother insists, and we end up rewriting the recipe together, a compromise, my interpretation atop her foundation.

It’s April, 2020; we’re in Early Pandemic, though we don’t know that yet. We’re still canceling dinner plans and telling friends, “No worries, we’ll have you over in July.” My partner, Marguerite, and I—the youngest females in our families—have by default become kitchen archivists. Our siblings either lived too far away or declined interest in recipe books when we dismantled our parents’ houses. That’s how we wound up with a book of recipes from my father’s mother, into which my mom at some point added several loose-leaf pages written in her mother’s hand; many of my mom’s own recipe books; a book of recipes belonging to Marguerite’s mom; a photocopied compendium of Marguerite’s Brazilian grandmother’s recipes, typed out in Portuguese; and a few of Marguerite’s dad’s mother’s recipes, sent by a cousin. There is also a self-important little notebook detailing everything Marguerite and I made from March to November of 1994. All of this takes up a full drawer in the pantry.

We’ve decided to cook and bake our way back in time. When the pandemic began I’d just finished a memoir about Wales, where I went for grad school in 1983 and, in spirit at least, never quite left. The book is anchored in the Welsh word hiraeth—pronounce it HERE-eyeth (and please, for heaven’s sake, roll the “r”)—for which there is no cognate in English. Hiraeth is a name for that intractable longing you feel for someone or something—a home, a culture, a language, even your younger self—that you’ve lost or left behind. Or perhaps for the goal that hovers inaccessibly in the future, forever out of reach. In Welsh terms, hiraeth is embodied by Arthur, King of the Once and Future, but never of the Present.

Hiraeth is, above all, an acknowledgement of the presence of absence. Maybe, just maybe, cooking can chase away the ghosts of yearning—allowing me to reach into the past for inspiration while fiercely and fully occupying the energies of the present.

I’m too young to remember the feast on Christmas night: cousins, aunts, uncles, parents, grandparents seated around my maternal grandmother’s—Grandma Dreher’s—table, devouring roast turkey and its accomplices. (Never my favorite meal.) By the time my memory kicked in, my mom and her sisters had decided it would be easier for my grandmother if they set up a cold buffet instead: sliced ham; sliced turkey from Christmas Eve; crusty rolls; Cole slaw from Henry’s, in Verona, New Jersey; and “Pat’s” potato salad. Other dishes might come and go, but the season’s holiness lived and died with these five. The slaw had to be from Henry’s—they put caraway seeds in it, which looked suspiciously like mouse droppings, I thought—and only Pat, my mom, could make the potato salad.

In a handwritten collection she compiled for me in 1984, she subtitles her potato salad recipe “My Favorite Stand-by.” Throughout the year my mother would call downstairs to anyone still at the breakfast table—“Could you check on the potatoes?”—meaning, did the baking potatoes she’d set to boil first thing in morning still have enough water in their pot? She made her potato salad for everything from Christmas to summer picnics. My mom wasn’t an adventurous cook or an experimental one, but she knew a simple secret: Learn what tastes good to you, and make that. And then make it over and over and over again. Because what tasted good to her tasted good to most people in the second half of 20th century America, my mother was universally deemed an exceptionally good cook.

Today, nestling potatoes into a panful of water and setting them on the stove is like stepping back into an intimacy I’ve known all my life. After I’ve cooled and cut them, I consult the recipe and bark out a laugh. It’s a German-style potato salad flavored with onion, celery, sugar, cider vinegar, sweet pickle juice, and…mayonnaise. Next to that last ingredient my mom has written in parentheses, “(as much as you prefer).”

“Not as much as you, Mom!” I shout to the ceiling. Her potato salad swam in waves of mayonnaise. In my iteration I put in just enough to coat the potatoes, enough to serve as the field on which the sweet and sour notes—the flavors of life itself—stake their flags for dominance.

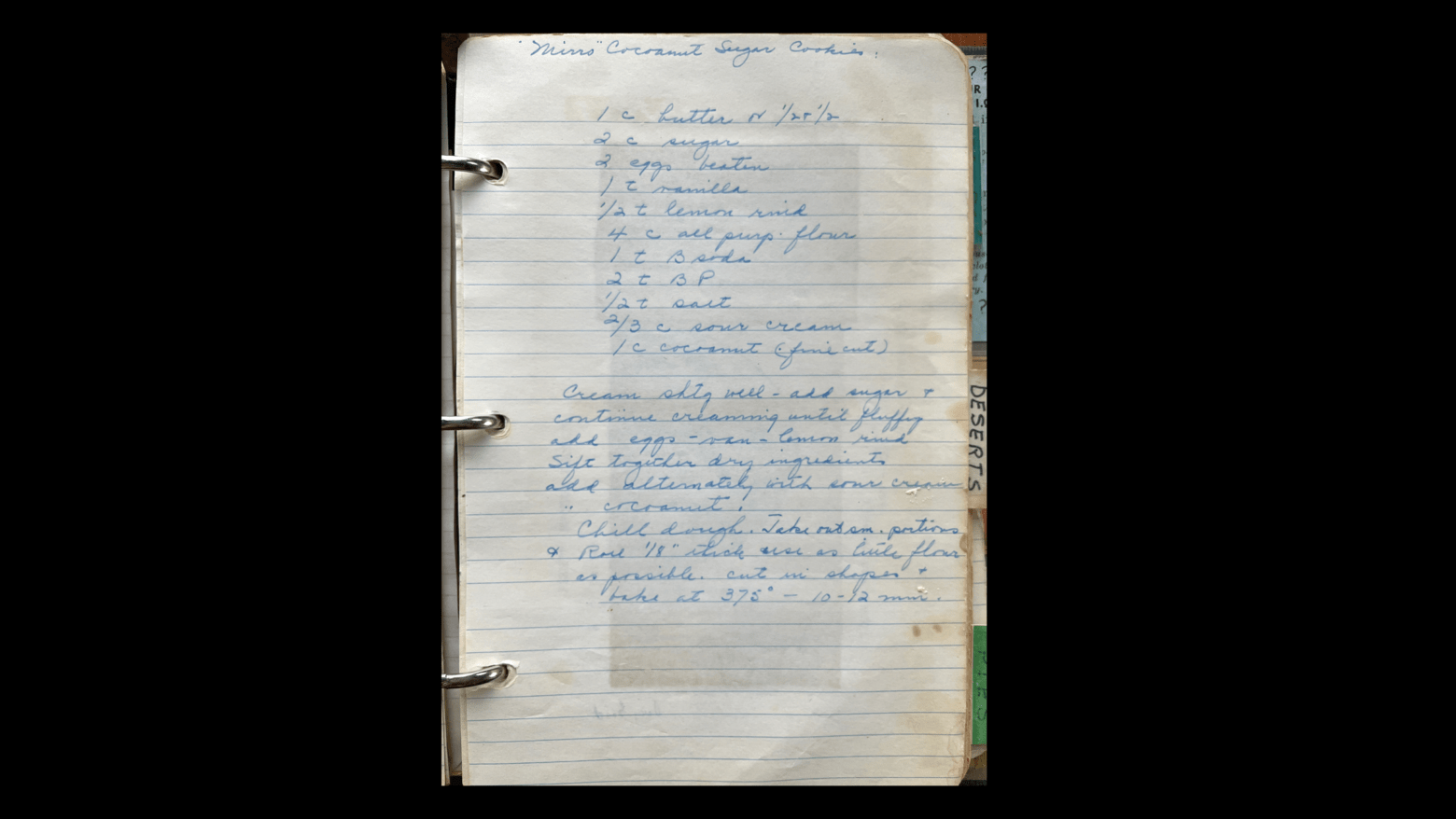

We make the recipe my Grandma Petro—Mary—labeled “mirro” coconut sugar cookies not for memory’s sake, but for coconut’s. My mom didn’t care for it. In fact, her whole family—my childhood arbiters of taste, securely American enough to cultivate German traditions—seemed to find it downmarket somehow. But Marguerite and I love it. My dad loved it too. Both of his parents came to the US from Hungary as toddlers, and I used to find their hearty meals and cultivation of American traditions embarrassing. Mary, who had a reputation as not just a “good cook” but a “pastry chef,” clearly embraced coconut, though I don’t remember her making these cookies.

I do a little research. “Mirro” appears to be some kind of mid-century cookie press. Mary must’ve admired the dough but disdained the press, and in the immortal imperative tense of recipes, she commands me to roll the dough and cut out shapes. I choose a circle and a star.

Later I discover flour even in my socks. But the cookies are a revelation. All those rising agents ensure that they puff up like politicians. They’re soft and airy, more like tiny domed cakes with crisp edges. And they’re not too sweet. They pose a mystery—what is this flavor?—that’s only solved after you’ve swallowed, when you exhale a gentle gust of coconut. Sprinkles are my apostatic addition.

I make these on Easter. As I’m teasing the cookies off the pan onto the cooling rack, a resurrectional shiver overtakes me. I feel as if I’ve ignited something latent, something that’s lain dormant all these years and has just flared to life again.

The recipe makes 90 cookies, and the day Marguerite and I eat the last of them we’re conscious of an absent spot in the fridge where the cookie tin has sat for weeks. Sometimes when we finish eating something we’ve made, it feels like the person who bequeathed us the recipe has died all over again.

With the absence of company to feed or holidays to observe, our meals become unmoored from the calendar. We make “Autumn Fruits Cornish Hens” in early June. Marguerite’s mom, Heline, “went through a Cornish hen phase,” Marguerite says, in the 1970s and ’80s, after the family moved back to the States from Brazil. Heline was from a rare tribe of Brazilian Presbyterians in the city of Fortaleza. She came to college in the States and met Marguerite’s American dad, and they married and had their three children in Virginia. When Marguerite was two, they moved to Brazil and didn’t return for good until she was 14. By the time I met her mom, in the ’80s, Heline was deeply bilingual in two culinary traditions.

It’s in Marguerite’s recipe book, at the back, that we find a Parade Magazine clipping for the autumnal Cornish hens, dated 1986, sent by her mom. The recipe is on the same page as an ad for “Chicken Duets,” from Swanson: “Tender nuggets with tasty stuffings inside.” Ham & Cheese, Spinach & Herb, Mexican, and Pizza-Style. They look pretty good.

Purists, please know I didn’t marinate the hens overnight in garlic, oregano, salt and pepper, red wine vinegar, olive oil, prunes, apricots, green olives, and capers. I’m sad to report that Julia Child was talking about me when she said that only a fool doesn’t read a recipe thoroughly before embarking on it. No matter; the ingredients, abetted by white wine and brown sugar, do the trick.

Did you know a Cornish hen is just a two- to four-month-old baby chicken? We didn’t. They are extremely tasty. But I believe that we as a people have moved on from these diminutive fowl, and while we retain the ability to cook them, we’ve lost the skills necessary for eating them. They look resplendent on the plate, but the hens are diabolical to eat. Lots of complex knife work for little reward.

“It’s like eating fish with bones,” Marguerite says unhappily.

I decide to pick the remaining two hens clean, add the pieces to the sauce, freeze some of it and serve the rest the following night in bowls over rice. A sacrilege.

When it comes to bolo de aveia (oatmeal cake), it’s the word “cake” that throws us. When I take the square, Pyrex pan out of the oven we discover a dense, mottled, two-inch-high bed of something that looks like a mud flat. Or maybe pecan squares, gooey, sweet, and fantastically sticky, begging to be divvied up brownie-style.

Had I given thought to the ingredients, rather than just rushed them onto a shopping list, I’d have realized there was no flour of any kind in this recipe, so a cake was never possible. No matter—we are in love with the results. It surprises us with its un-American lack of nuts, its un-Brazilian insistence on oats. No crunch, but a complex texture and plenty of heft.

The recipe is from Marguerite’s maternal grandmother, her vovó, who liked sweets to be sweet, and—coming from the northeast of Brazil, a region of perpetual drought—insisted on filling water glasses to the very rim to indicate plentitude and well-being. I’m also guessing she wasn’t a sufferer of fools. Because I’ve read the two-sentence instructions beforehand (I learned my lesson), I admire the built in presumption that one will have had the foresight to not only save the egg whites, but beat them to snowy peaks. And, of course, to bake the batter.

“These are my grandmother’s recipes,” notes Marguerite, “but most middle-class families would’ve had maids—they still do. It’s the maid who does the baking.”

I’m pleased that Marguerite’s vovó trusted the maid to bake the batter. We do it ourselves, at 350 F for 35 min.

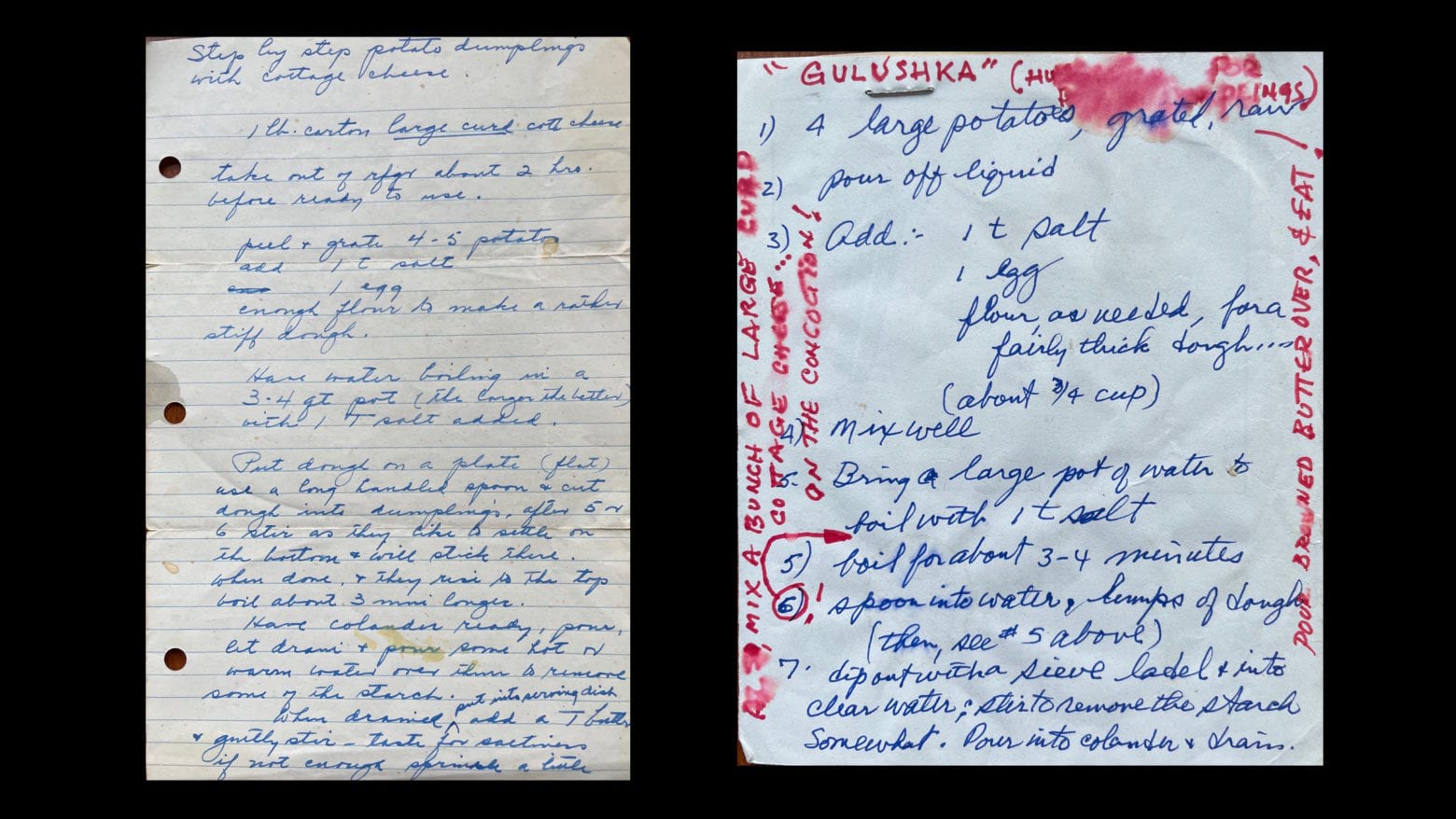

Across the years, recipes often involve a game of Telephone. My Grandma Mary, secure in two languages, entitled a recipe she copied out twice—once in black ballpoint, once with her blue fountain pen—“Potato Dumplings with Cottage Cheese (lump style).” My dad wrote it for me on the back of a “Far Side” cartoon and called it, “Gulushka.” Someone on the Internet calls hers, “Haluska.” Someone else calls hers “Shlishkes.” I call mine, “A Mistake.”

When my dad turned 90, four months before he died, my family gathered to create a Hungarian feast for him, just as we’d made a German feast when my mom turned 90, six months earlier. I made goulash and gulushka; my nephew brought treats from the Hungarian Pastry Shop in New York City. I thought my dumplings were passable; my dad appreciated the effort but pronounced them too big.

Here’s his recipe, copied from his mother’s:

4 large potatoes: grated raw

Pour off liquid

Add: 1 t salt, 1 egg, flour as needed for a thick dough (about ¾ cup)

Mix well

Bring a large pot of water to a boil with 1 t salt

Spoon lumps of dough into water

Boil for about 3-4 minutes

Dip out with a sieve into clear water; stir to remove the starch. Pour into colander and drain.

He then remembered two key elements that he added in red marker:

Mix a bunch of large curd cottage cheese on the concoction!

Pour browned butter over and EAT!

Mary is more specific, telling me to put the dough “on a plate (flat)—use a long handled spoon and cut dough into dumplings.” I don’t understand why the long handle is important; maybe that’s my problem. The smell as the dumplings cook wakes my memory; later, the mouthfeel—slippery, viscous butter and bumpy cottage cheese—confirms my inklings: I know this food. The dumplings themselves, though, are leaden. Hard, dense, not entirely cooked. Play-Doh might taste better.

This was Mary’s signature dish and I feel disloyal spoiling it. There was something important about gulushka, an aspect of anchorage, a ritual. I remember her pouring the liquid butter at the table, while I kept my own suspicions about the damp cottage cheese to myself. The glory and exultation of butter—real butter! (At the time we used margarine at home.) A taste that felt like a birthright of being human. But I also remember my mom and her sister, June, talking on the phone about Mary’s “heavy” food; left unsaid was that she, too, was heavy. Everyone said I looked like her. And that’s how fear and guilt enter flavor, even the flavor of a birthright.

Marguerite and I recognize failure when we taste one. “Maybe if you’d boiled them a little longer?” she offers, molaring what should be soft. On the second night I fry the dumplings in duck fat, serve them thoroughly cooked and browned atop a white bean and tomato stew, with cilantro coulis drizzled on top. Now we’ve abandoned the past, returned to our own gentrified time and taste, disguised my heritage. Do we not have the palate to enjoy gulushka, or did I fail my dad and his mom? No one is here to tell us.

Our ancestry wades right through mid-century America; Jell-O had to happen sooner or later.

The recipe, “Sherry-Strawberry Mold,” is offered by Cindy, Marguerite’s cousin on her father’s side, who has squirreled away a few recipes from her “Girma,” as Cindy and her sister called their grandmother (a kid-brilliant reduction of “Grandma Irma”). “She cooked from memory and never owned a cookbook,” Cindy recalls.

“We called her, ‘Grandmother,’” adds Marguerite, raising her eyebrows.

I almost back out at the supermarket, when a woman snickers as I put Strawberry Jell-O in my cart. It’s no better at the liquor store, where I have to ask where I can find cooking sherry. “Sherry?” asks the young clerk. They have only one brand. At home we each take a sip, and pronounce the sherry akin to what you’d taste if you could siphon allergens and pollution out of very humid air.

The written recipe includes an analogy, and I admire that. Chilled gelatin should have a consistency “like an unbeaten egg white.” That’s helpful. The Jell-O mixture is mildly sweet—it includes the sherry, fresh strawberries, a diced banana, and sweetened, shredded coconut—and I’m intrigued that it contrasts with a savory topping made of cream cheese, orange and lemon juice, salt, sugar, and paprika, of all things.

I forgo the molds and serve Jell-O and topping laced together, parfait-style, for dessert. Aesthetically, the parfaits are stunning. But they present a curious challenge: we struggle to taste any of the component parts. The sweet Jell-O and tangy sauce wholeheartedly cancel each other out, leaving an impression of textures—including a curious fizzy quality—rather than flavors. It’s a pleasant mix, but a little like disappearing into a flavor black hole.

It occurs to us that we’ve culturally misappropriated this recipe. It was doubtless meant as a side salad for a southern luncheon—Marguerite’s grandmother was a Virginia matron—and we’ve unconsciously construed it as dessert. This adds to our disappointment, and is weighed down by another association: In the hospitals and nursing homes where we shepherded our parents through decline and then death, Jell-O is as inevitable as catheter bags. And it is always served as dessert.

13 April 1994—“Cavatelli with Minced Tofu Pups”

20 April 1994—“Pasta in Cauliflower and Mushroom Mush with Strawberries”

20 July 1994—“Couscous and Artichoke Bake”

I avoid the more “exotic” fare in our little notebook cataloguing the meals I invented in 1994, and choose a recipe for stuffed shells instead. I haven’t made this dish in 26 years. It turns out I had more energy when I was 34, not to mention more time and a stronger constitution.

My youthful recipe calls for two from-scratch sauces, a red and a white. Was I insane? Drunk? Did I have all day? This time I use organic red pasta sauce from a jar, and skip the white sauce entirely, replacing it with slabs of mozzarella cheese. (It’s my own recipe, so I figure I’ll do what I please; it’s not like my younger self is going to haunt me). Early pandemic shortages wreak their mischief, too; people have apparently squirreled away pasta shells for the coming Armageddon. But eventually I find manicotti tubes and decide those will do.

The dish bubbles satisfyingly when I lift it from the oven. These manicotti eschew ricotta and are stuffed instead with onions, garlic, mushrooms, chickpeas, cashews, and parsley, sautéed in white wine, blended in a food processor and mixed with softened cream cheese. One bite sends Marguerite back to grad school again. We live in an apartment in Providence, Rhode Island and have a fish named Wilma. Marguerite’s dad has just retired as a Presbyterian minister, and my parents stopped by last week on their way to the Cape from New Jersey. My mom dropped off a zucchini bread.

What I taste is wholeness of so many kinds. The most insistent is the dense, overturned-earth flavor of the mushroom mixture, combined with a strong mouthfeel memory—the pliable softness of the pasta sliding into the creaminess of the filling—plus an “upfront” aroma from the wine and tomatoes that rises like a spirit rather than settles. The recipe may hail from nearly half our lives ago, but tonight it’s a real dish, bubbling here on our table in 2020, a meal capable of staining the tablecloth, of feeding us, delighting us, of blending who we were then with who we are now.

There is one dish we didn’t include in our experiment because it’s omnipresent in our lives: the crust for the pie. It’s Mary’s cream cheese pie crust, and I make it several times a year. My friends make it too. So do people I barely know. I once spent a morning copying it out for fellow passengers on an Inuit cruise ship above the Arctic Circle, and an evening copying it for fellow hikers at an inn in Tuscany. I don’t remember Mary making it; by the time I was learning to love it I thought of it as my mom’s pie crust, although she always gave her mother-in-law credit. In the book she made for me it’s called “Grandma Petro’s Pie Crust—Old Faithful.” I can list its imperatives by heart: cream together ½ cup Crisco + 3 oz of cream cheese; sift together 1 ½ c flour, ½ tsp salt, 2 tbs sugar; blend with your hands to form a ball; divide in half, roll between two sheets of waxed paper. My mom added encouragement on the recipe card: “Comes off easily!” You then add whatever fruit you wish—generally apples or peaches, plus ½ cup of sugar, ¼ cup of flour, and some cinnamon, and dot with butter—and bake for 45 min at 400 F.

What’s vital here is the cream cheese. It lends the crust a tangy mellowness that slips into the gills and up the nose, as well as a golden-brown, mottled, flaky richness of texture and color. It’s also what makes the crust kin to my grandma Mary’s Viennese Cream Cheese Pastry. It’s only in writing this essay that I’ve realized the Viennese recipe gave birth to the American one.

I discover that Mary wrote out the directions not once but three times. The version I follow is dated 1969, with a note that reads, “Same as my 1933 one.” On the next page is a slightly different version labeled “Original Viennese,” with a note that says, “Cleveland—Parkhill in the 1920’s.” (My grandmother was born in Hungary in 1893, and when her family brought her to the States they made a beeline for the Hungarian community in Cleveland.) This one calls for Crisco—Procter & Gamble introduced it in 1911, the first all-vegetable-oil solid shortening available to American bakers—and I think this is the recipe Mary eventually adapted into her pie crust. But there’s still a third version, ever so slightly different and somewhat streamlined, called “Holiday Cheese Tarts.” This one directs me to put the dough in the “ice box.”

I also have my mom’s recipe—the same streamlined iteration as “Holiday Cheese Tarts”—and, dearest to my heart, a copy she wrote out on an 8 ½ x 11 sheet of paper, now deeply folded and stained, which she sent to me when I was studying abroad during my junior year in Paris, in 1980. Marguerite and I had just met there, and together we made the tarts for our French hostess.

This time I follow the 1969 version because it affords the most instruction. I’ve made the Holiday Cheese Tarts before, but never the original Viennese pastry, and do so with some trepidation. I make a ball of dough. I let it sit overnight. And then I hit a wall. “Roll ½ inch thin, fold in half, fold over ½ again and ½ again, making 4 layers.” Mary has helpfully taped photos from a magazine on the back of the recipe, but they contradict what she tells me to do. I try to fold from every direction of the compass, and finally, give in to a howl—a long, wretched howl from the gut, dusted with flour.

Somehow, alternately folding more howls into whimpers and filling with curses, I muddle through and wind up with several dozen three-inch squares of dough. I fill some with jam, others with a nut-and-sugar mixture, and then pop them in the oven.

Watching them bake, I see that my pastries don’t stay closed. They roll on their backs like blissful puppies, displaying their soft bellies for all to see. I swear I can smell the aroma of the Old World seeping from the oven; in this case, the complex, unwieldy Austro-Hungarian Empire that wasn’t taken from my grandmother, or lost, but from which her parents willingly absented themselves. Did they feel hiraeth here in America for their former home, or did they bake that hiraeth away? I’ll never know. What I do know is that in Cleveland, Ohio, my Grandma Mary inherited a recipe still signified by its Viennese origins, and over the next 40 years or so—with the help of Procter & Gamble and the metamorphic weight of her unabashed desire to become as American as, well, apple pie—she baked that recipe like a geneticist, selecting for ease and simplicity without abandoning flavor, and bequeathed to her daughter-in-law the pie crust recipe for which Pat became as famous as she was for her potato salad, perhaps even more so. The same recipe that Pat’s daughter carried around the globe.

As soon as I put one of the ugly little marvels in my mouth, taste rockets back to life. Not just any taste: a fundamental taste that transports me to a place of satisfaction and well-being—a place associated with Christmas, childhood, parents, family, warmth, twilight, a life yet to be lived. But those memories are incidental; they’re like the sprinkles I put on top of my cookies. And that’s because this fundamental taste elevates me beyond the personal to a place more important, more universal, more capable of being shared: a place where flavor is its own boss rather than the servant of memory.