Technically, it began with a single cup of coffee thrown in a policeman’s face. But as with almost all riots, the one at Compton’s Cafeteria centered less on a particular moment than the years of abuses that led to it.

There are no reports of the temperature of that coffee—all details from the riot remain sketchy—but I like to imagine that when it hit the officer’s skin, the coffee sizzled like a pan of chicken grease. That this police officer carried the burns for the rest of his life. That on his death bed, his children gazed down at his face and wondered—for the millionth time—where their father had gotten this constellation of scars he’d forbidden mention of.

Who, his children wondered, had fought back?

Suzan Cooke:

Amanda St. Jaymes:

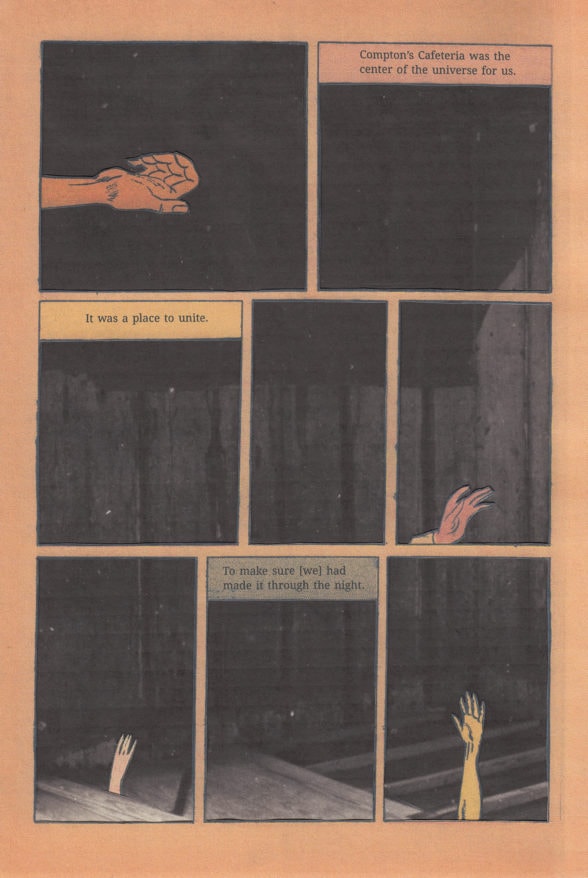

We don’t know the name of the trans woman who threw the coffee in that early morning hour of August, 1966, but back then Gene Compton’s Cafeteria was the spot in San Francisco’s Tenderloin district for trans women and drag queens to congregate. One cup of coffee could buy hours sitting in a vinyl and chrome booth at the Hopper-esque corner diner. In a 2017 interview with Man Repeller, patron Felicia Elizondo described Compton’s as “the center of the universe for a whole bunch of the queens, the sissies, the hustlers, the kids who were thrown away by their families like trash.”

Felicia Elizondo, interviewed by Zachary Drucker for Vice in 2018:

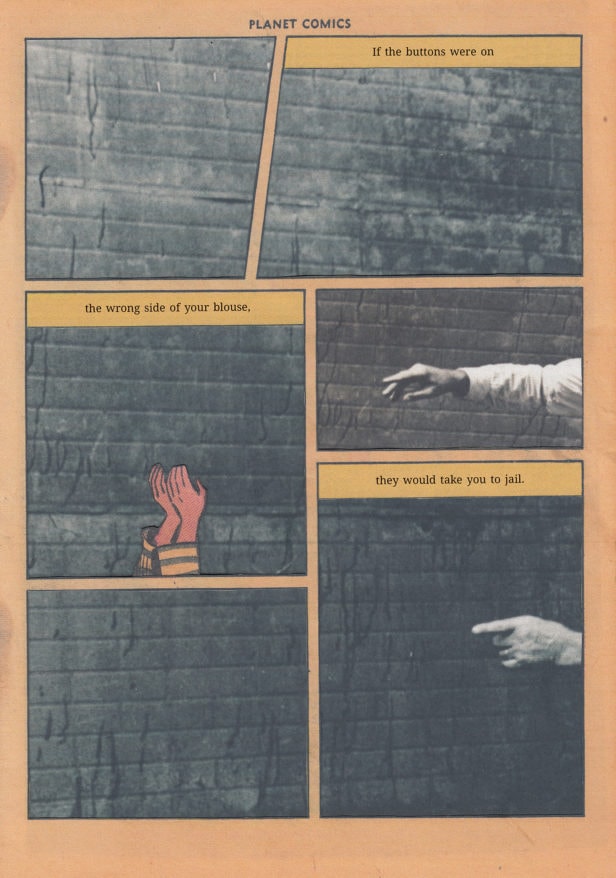

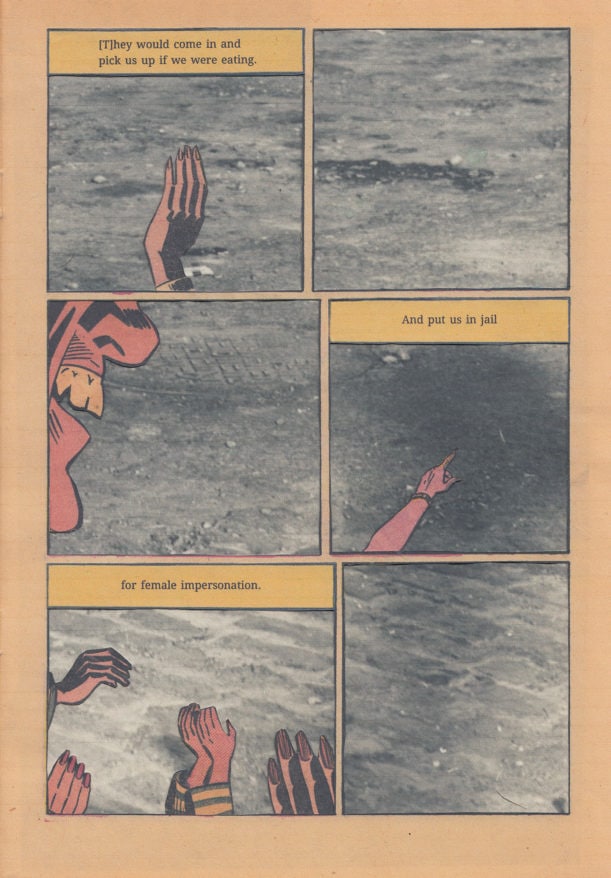

The popularity of Compton’s Cafeteria represented the end result of a targeted campaign. From 1863 to 1974, San Francisco’s municipal codebook included a law stating that it was illegal for any individual to appear “in a dress not belonging to his or her sex.” As Tenderloin resident Suzan Cooke tells historian Susan Stryker in the 2005 documentary Screaming Queens: The Riot at Compton’s Cafeteria, “Police would give the people who were indeterminate gender the message that they belonged [only] in the Tenderloin, which at the time, was kind of a gay ghetto, a very slummy gay ghetto.”

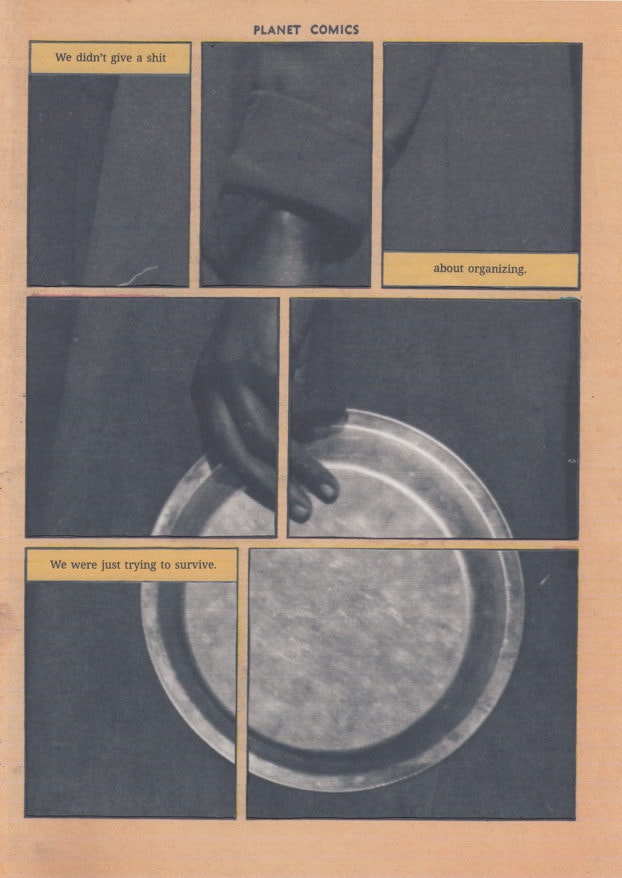

And even in the Tenderloin, trans women often remained unwelcome—turned away from gay bars, driven off the sidewalks by police. Elizondo characterized the choice of Compton’s as simple: “[W]e had nowhere else to go. The end.”

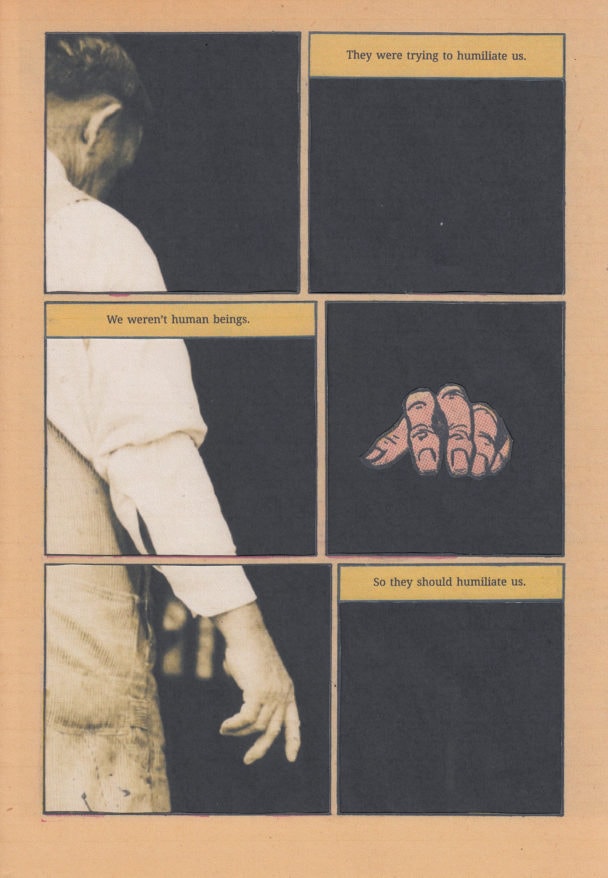

Pushed into the Tenderloin, pushed into the one business where they knew they could linger, and still, the cops appeared regularly when quotas needed filling.

Amanda St. Jaymes:

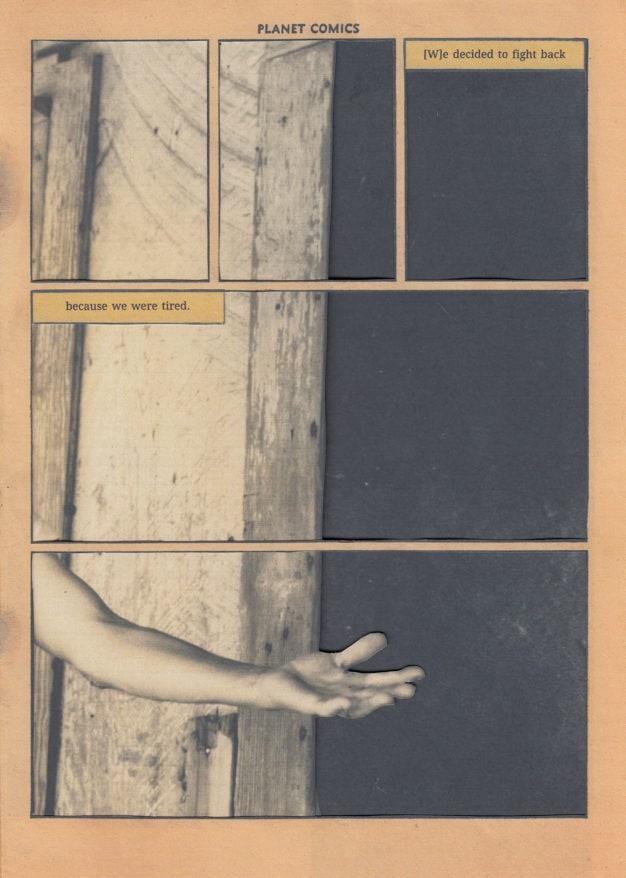

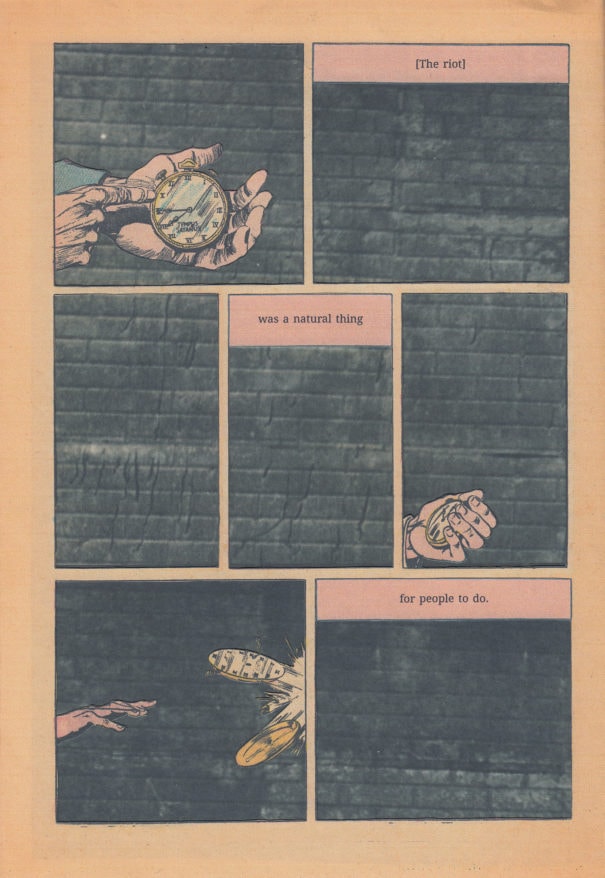

After that first cup of coffee, events escalated quickly.

In Screaming Queens, Amanda St. Jaymes, the only known participant in the riot to be interviewed, tells Susan Stryker, “Someone had coffee thrown in his face, and there was tables turned over…Oh, the sugar shakers went through the windows and the glass doors. I think I put a sugar shaker through one of those windows.” Soon the fight moved outside, with a newsstand set afire, a police car smashed up. “And of course, they had the paddy wagons, and they were putting people in the paddy wagons as they would come out and start fighting.” St. Jaymes smiles as she speaks. “They fought up and down the streets.”

For much of the last year, I’ve been researching riots and making comics from the words of riot participants and government reports. I’m consistently struck by the descriptions of joy (italics mine):

Mayor LaGuardia’s Commission on the 1935 Harlem Riot (never officially released to the public): “[M]any youngsters who could not be classified as criminals joined the looting crowd in the spirit of pure adventure.”

Two teenage girls drinking looted wine during the 2011 London Riots, interviewed by Leana Hosea for the BBC: “It was madness. It was good though. Good fun.”

Amanda St. Jaymes, talking to Susan Stryker: “There was a lot of joy after it happened. A lot of them went to jail, but there was a lot of, ‘I don’t give a damn. This is what needs to happen.’”

News reports typically emphasize the violence and destruction caused by rioting, and certainly, the initial effects on a community can be devastating. But perhaps the element of joy should be represented as well: the “pure adventure” of acting, however briefly, outside the oppressive strictures of the state. The “good fun” of it all.

The two teenagers interviewed by the BBC during the 2011 London Riots go on to describe the function of rioting: “That’s what it’s about: showing the police we can do what we want… showing the rich people we can do what we want.”

In 1966, not a single news report mentioned the Compton’s Cafeteria riot. It wasn’t until 1995 that Susan Stryker found a brief reference to the riot in San Francisco’s GLBT Historical Society Archives. Almost a full decade later, she finally brought the event into public consciousness with the release of her documentary.

Still, no one knows the exact day the riot occurred. By their nature, historical narratives drastically simplify—excising some details and amplifying others—and when the original event itself goes unrecorded for so many years, perhaps any cohesive narrative is suspect. Felicia Elizondo, perhaps the most eloquent spokesperson for Compton’s Cafeteria’s legacy, can’t even remember if she was in the diner that night.

Considering that, one detail I’m unsure whether to include here was the presence of the Vanguard Gay Liberation Youth Movement and Organization in the Tenderloin. This short-lived activist group sporadically met at Compton’s Cafeteria before being banned by management. To protest their banning, Vanguard picketed Compton’s for a day in July, and Susan Stryker sees the group’s nascent activism as key to the abrupt decision of that unnamed woman in August to throw her cup of coffee in a policeman’s face.

Like Elizondo (“We didn’t give a shit about organizing”), Tamara Ching appears more skeptical of a connection between Vanguard and the riot. Ching tells Stryker in Screaming Queens, “We heard about Vanguard, but being a person of color, I didn’t feel like I belonged.”

Felicia Elizondo, interviewed by Neal Broverman for The Advocate in 2018:

Tamara Ching:

The months following Compton’s saw some of the country’s first stirrings of trans activism—based entirely in the Tenderloin. At Glide Memorial Methodist Church, located two blocks from Compton’s Cafeteria, activists founded the first known trans support group, Conversion Our Goal (COG). While short lived, COG was particularly integral, according to Susan Stryker, as “an initial point of contact for transgender people seeking medical services.” Around the same time, the city began offering Tenderloin-based anti-poverty and job training programs, previously unthinkable opportunities for trans women who wanted to leave sex work.

While the Compton’s Cafeteria riot remained unreported by the media and was largely forgotten in San Francisco by the seventies (the police claim to have no resulting arrest reports), the developments in the Tenderloin following that night attest to its impact. After Compton’s, the city could no longer claim not to see the Tenderloin trans community.

Tenderloin residents also suggest police harassment lessened in those months following the riot, but the law forbidding “dress not belonging to his or her sex” continued as a basis for arrest until finally removed from the municipal code book in July, 1974.

Today, the ACLU identifies 49 “anti-trans bills” making their way through state legislatures. From October 2018 to September 2019, the Trans Murder Monitoring report documented thirty murders of transgender people in the United States, with 90 percent of the victims identified as “trans women of color and/or Native American trans women.”

In San Francisco, six blocks of the now gentrifying Tenderloin have been officially designated as the “Compton’s Transgender Cultural District.” In 2018, the nearby Tenderloin Museum premiered a theatrical reenactment of the Compton’s Cafeteria riot that ran for nearly three months.

As for the site of Compton’s Cafeteria? It now holds a Federal Bureau of Prisons “reentry facility,” a halfway house run by the private prison operator Geo Group. In the building, ankle-monitored inmates from state and federal prisons serve the last six months of their sentence.

At the 2019 Queer Liberation March held on the 50th anniversary of Stonewall, demonstrators chanted, “Stonewall was a riot! We will not be quiet!”

When reporting on the march, progressive news outlet Democracy Now! quoted this chant and moments later referred to “the Stonewall uprising” (italics mine).

Writing of the 1992 LA riots in her book Carceral Capitalism, poet-scholar Jackie Wang describes the leftist habit of substituting the words “rebellion” or “uprising” for “riot”:

This attempt to reframe the public discourse is born of “good intentions” (the desire to combat the conservative media’s portrayal of the riots as “pure criminality”), but it also reflects the impulse to contain, consolidate, appropriate, and accommodate events that do not fit political models grounded in white, Euro-American traditions.

Protests are, by definition, reactive to oppressive systems, but at their apex, riots function as if these systems don’t exist. Terms such as “rebellion” and “uprising” similarly signify political intent, and while often appropriate, they can also be reductive. The moments after the first thrown brick or cup of coffee in a policeman’s face offer a brief glimpse of an entirely alternate world: one in which the rioters live uncontained and free.

Compton’s Cafeteria happened three years before Stonewall, and like that more chronicled and mythologized event, Compton’s Cafeteria was a riot.

Tamara Ching, interviewed by Nicole Pasulka for NPR’s Code Switch in 2015:

The words of Martin Luther King, Jr.—the most frequently quoted and misquoted of all US revolutionaries—can still surprise, and the civil rights leader’s incisive definition of “a riot” is no exception. In a 1966 interview, coincidentally airing on CBS only weeks after Compton’s Cafeteria, King told Mike Wallace, “I think that we’ve got to see that a riot is the language of the unheard.”

And then he asked the most pertinent question: “And, what is it that America has failed to hear?”

A note on sources:

Unless otherwise noted, all quotes from Suzan Cooke, Amanda St Jaymes, Felicia Elizondo, and Tamara Ching are from interviews with historian Susan Stryker in the 2005 documentary Screaming Queens: The Riot at Compton’s Cafeteria.

Additional references:

Arresting Dress: Cross-Dressing, Law, and Fascination in Nineteenth-Century San Francisco by Clare Sears (2015)

Transgender History: The Roots of Today’s Revolution, by Susan Stryker (second edition, 2017)