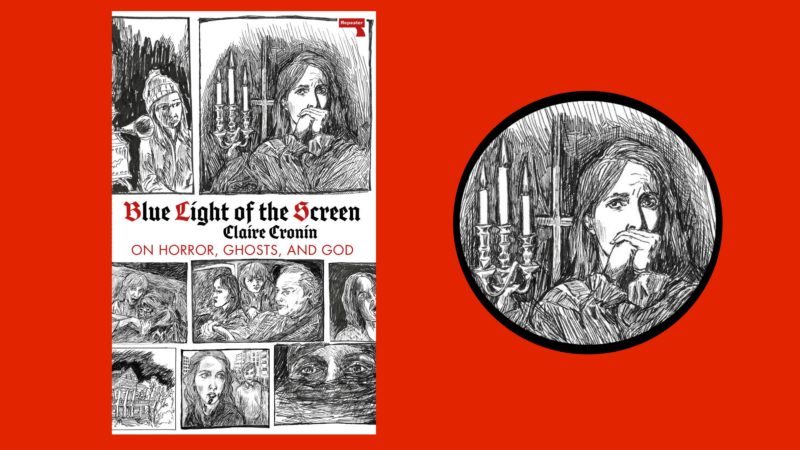

Claire Cronin is many things—writer, musician, academic, visual artist, poet—with a singular interest: horror films. Blue Light of the Screen, out this month, is an obsessive, flickering first work that combines several of Cronin’s talents (illustration, memoir, criticism, poetry) to approach horror films from every angle available to her.

Blue Light of the Screen, which Cronin wrote while completing an English PhD at the University of Georgia, is at once an investigation of Cronin’s familial beliefs, a compendium of film notes, and an academic treatise on technology, horror, and spirituality. Her taste in film is broad; she provides engaged notes on seemingly throwaway new releases, on classics like Don’t Look Now, and on highbrow Ari Aster features, which are also treated to understated summaries: “Headlessness in horror is rarely metaphoric.”

Cronin has always felt a deep pull towards horror, and specifically towards hauntings. Last year, she released Big Dread Moon, a Southern Gothic folk album similarly interested in spectres (though, with its wavering vocals and pared-down images, it sounds less like something for encountering ghosts and more like something ghosts would listen to). Explaining her fixation to herself is the true muscle of Blue Light. As she puts it, “certain horror plots return me to a story my mind’s already been telling.” Cronin’s subheadings—some of the most poetic and haunting writing in the book—often highlight the persistent dedication of her interests: “Forebodings, age six to thirty-three.”

Blue Light of the Screen is at its most exciting when Cronin weaves her concerns together—particularly when she compares her lifelong fascination with horror movies to her family’s committed Catholicism. When Cronin confesses to her father that she has an awareness of spirits, she learns that she has inherited a lineage: her grandmother once spoke to photographs of loved ones who had passed away. “I guess you got the God gene,” Cronin’s dad tells her.

Cronin reflects on communing with the dead, citing her family’s practice of waiting, after someone has died, “for signs that their soul has entered heaven.” She theorizes about what connects her family’s spirituality with her own magnetism towards ghost stories—in the process, she locates the most driving questions about human curiosity and sense-making. And she quotes deftly to support these connections. To tie a 2006 movie about a haunted video game together with Catholic mourning, she pulls from C.S. Lewis: “And grief still feels like fear: Perhaps, more strictly, like suspense.”

Because Blue Light pulls so relentlessly at horror and does so using every one of Cronin’s modes, the book crystallizes an obsession, demonstrating how art, ghost stories, and family myths can get deep into your brain. In real time, we see how Cronin’s watching infuses into her real life; it becomes impossible to tell if thought patterns originated “in half-remembered wounds” or were implanted by movies, “like the hyper-real, deep fake of a CGI.” And the most haunting thing, Cronin knows, is never finding an answer, knowing only that you will continue to be dogged.

—Maggie Lange for Guernica

Guernica: You seem to come to horror films from every direction, except making them, which we will get to. What about combining modes—like poetry plus theory or illustration plus memoir—do you find irresistible?

Claire Cronin: I definitely have my obsessions and my moods. I tend to keep making work around the same themes. I go to the same images. [But] I think I reach a point in one medium or mode where I come up against a limit of what I can express, and when I feel that, I shift to another form. It’s never a planned-out process, just a natural outgrowth of having dabbled in so many forms. I can move from writing songs to writing essays or to making drawings, instead of forcing myself to keep going in something that frustrates me.

Guernica: What do you find that’s different or that unexpectedly emerges when you switch modes?

Cronin: In writing this book, I found a tension: I’m in a PhD program; the genre of an academic monograph or article is one where you don’t talk about yourself. I’m trying to write something theoretical about horror, but can’t stop talking about my own life as an explanation. I’m going to tell you this stuff that might make me sound like an unreliable narrator; also I want you to take seriously my rhetorical positions about visual media.

In song-writing, there’s something more automatic and mysterious. The lyrics that come out make statements, make images, tell a story, but without the layers of complication that come with writing [prose]. In song-writing, I try to not think about myself or what I’m doing. I control the process as little as possible.

For lyrics, I’ve stolen things from my unfinished or unsuccessful work. Poetry has been the most devastated by that pillaging: for song lyrics, and for this Blue Light of the Screen book.

Guernica: Encountering your work, it’s almost like you need to get something out of your system— which gets crystallized in Blue Light of the Screen. Did you think of this book as an exorcism of sorts?

Cronin: It became something like that towards the end. It’s definitely confessional, [and] a little bit psychoanalytic, but I was the therapist and the patient.

Exorcism stories are not resolved at the end. Well, some exorcism movies do resolve the demonic possession, but even when that happens, there is still the sense that evil is floating around in the ether, waiting for its next victim. And in true stories of demonic possession, a victim often has to be exorcised many times, over many years. The threat doesn’t really go away.

In the case of my book, I did attempt to find resolution, but of course the problems that I deal with keep going. There’s still evil in the world and plenty of reasons to feel despair. Though I wanted to show that I’d found some self-awareness and faith through my struggles, I didn’t want to write a happy ending. I don’t believe in happy endings; they’re not true to life. At the end of a ghost story, something ominous still lurks.

Guernica: Why do you sketch while you watch scary movies? What does drawing allow you to access about horror?

Cronin: It’s a way to keep my hand busy while I watch scary movies. It was a kind of intuitive decision, [but] it made sense. I was thinking about what images are, what pictures are…I’m speaking mostly about photographic and filmic images [in the book], so something about making an image was interesting to me—another way of looking and conveying, with more imperfection. They became personal. I wasn’t trying to make a perfect copy [of faces on the screen]… the faces would start to look a little more like me or a person I know, which I thought was revealing. Those are the shapes you’re used to.

Guernica: So you make words, music, and images—and you have a central dominant interest in horror. Added up, this could equate naturally to making a horror movie. So, to pursue a negative corollary, why have you never written horror?

Cronin: I’ve never really tried. I don’t know why… I probably wrote a few stories as a child in English class. I’ve never tried writing fiction. I’ve never tried to write a screenplay. I always thought about myself as someone who would be bad at dialogue, but there’s so much dialogue in this book, it’s just real [and transcribed from life]. I’m already drawing from poetry and academic writing, these lists and memoir writing…there’s the ghost of a screenplay haunting this book, as another form that could be in there.

Guernica: You write about returning to certain horror movies frequently; I was wondering what music you return to continually?

Cronin: I do listen to horror movie soundtracks, but they’re more fun than scary—classic stuff like Goblin’s soundtrack for Suspiria or John Carpenter’s for Halloween. I spend a lot of time listening to composer Marcus Fjellström while I work. I discovered him by listening repeatedly to the soundtrack for The Terror, a horror TV show about arctic explorers. And I like to listen to “holy minimalism” music during the day too, mostly from Arvo Pärt, but that’s more saintly than demonic.

Songs with lyrics that really get me: old folk songs, brutal, straightforward lyrics. I find those chilling. A lot of murder ballads, a lot have stories of women who have been victimized in certain ways. I love the very old song “Twa Corbies,” which is about ravens who find the dead body of a knight. The more recent (like nineteeenth-century) Irish folk song “Johnny I Hardly Knew Ye” is a terrifying anti-war song, depending on the version you listen to. And I learned the classic folk song “Barbara Allen” when I was first playing guitar as a child. I enjoyed how tragic it was even then. When a song is ancient, there’s something about that that’s eerie.

Guernica: In one passage—about anodyne refrains at funerals and the way we talk about the dead—you express some concern for the ghosts that might overhear this. How much do you worry about the mental state or happiness of potential ghosts?

Cronin: I think about that all the time. Maybe I was led there from horror; fictional horror does lead you to have empathy for the ghost, [because it’s] an investigation of trauma the ghost endures. If it’s melodramatic, it ends with redemption or peace for the ghost. Or, like in The Grudge or The Ring, the ghost keeps on being evil and trying to kill everyone.

I’ve spent a lot of time reading about real hauntings. I’ve been on a handful of ghost tours, I’ve watched paranormal reality TV shows, and I feel offended by the way the dead are treated in these non-fictional ghost accounts. These are real people—whether or not you believe in ghosts or the afterlife—that died, in horrible ways. It’s disturbing that the living want to exploit that, or draw some thrill there. It feels totally unjust. And [it] says something sad to me about our relationship with history. I have to start a ghost advocacy group.

Guernica: Another thematic refrain of your book is removing the antique from the uncanny. You get emails from your mom about evils, you investigate the religious demonologists of YouTube, you consider the ghostly quality of new photos on Facebook of your cousin who passed away. So final note here: tell me what’s interesting to you about how superstition functions on the internet.

Cronin: The fringe belief stuff is genuinely terrifying and has only become more terrifying since I wrote this, as conspiracy theories radicalize into hate groups. The internet is a dangerous place running on its own logic. [But] the internet is [also] really spectral, because it’s so virtual. Being connected through the invisible internet makes it feel like images are appearing out of nowhere. That is very haunting.