By Chloe Pantazi

We have all been children, but few of us children of war: so a retrospective of Chim, one of the twentieth century’s most prolific photojournalists, at the International Center of Photography, reminds us. “We Went Back: Photographs from Europe, 1933 – 1956” returns us to the formative years of 20th century Western culture through black and white images of pre-war France, Spain in civil war, and post-war Germany and Italy, among other parts of Europe. But the most captivating of Chim’s places isn’t geographical. Rather, it’s a place in our past we can all lay a claim on: Chim’s photographs seek to reassemble the childhood of a lost generation.

The children depicted in “We Went Back”—named after Chim’s 1947 photography series of war orphans printed in an issue of This Week—are mostly refugees. In a sense, the photographer was a refugee himself; before he was Chim—a pseudonym that he took professionally, and an abbreviation of his real surname—he was David Szymin, born in Warsaw in 1911 to a family of publishers of Hebrew and Yiddish literature. On his travels, becoming a photojournalist in Paris in 1933, Szymin found that many had difficulty pronouncing his name, so he lost it and chose to work under this new one (pronounced shim). After the Second World War, Chim published as David Seymour, a name he probably picked up living in Medmenham, a small town outside London, England where he worked inspecting aerial photographs for evidence of German offensives during wartime. The war was the blind spot of Chim’s career: as a caption in the exhibition tells us, he published nothing between 1939 and 1945.

In his photographs, children look more like adults who have been stripped of their size and societal role—pushed into new occupations, relationships, new ill-fitting clothes.

The break in Chim’s career makes us look at the photos he did take, in the years surrounding the war—in France between 1933 and 1936, Spain from 1936 until the end of the Civil War in 1939, and then across Europe, in France, Hungary, Italy and Germany after the war—quite differently. By actively contributing to the war effort as a photo interpreter, Chim earns our respect, yet we are left wondering about the images that might have filled the void of the war years, and how—had he taken photographs during wartime—these might have contributed to our understanding. Nonetheless, Chim’s photos of the years before and after World War II construct a larger picture of the cultural upheaval of the era in stages: from toddlers sitting atop their parents’ shoulders at protest rallies, to soldiers preparing for combat or taking part in religious ceremonies held at army barracks, to women working land and factory jobs, digging up minefields and painting bombs in a munitions factory. As Chim offers up the every day lives of such adults working within the industry of war (as soldiers, munitions workers) we trust that Chim’s postwar photographs of children yield something close to their every day, as vulnerable innocents who—like the newborn seen suckling at its mother’s breast in a photograph taken of the crowd at a land reform meeting at the brink of the Civil War, in Spain, 1936—were virtually reared on the conflicts of their time. Looking at Chim’s photos of children, there’s a sense—one that we are familiar with—that war makes grown-ups out of children. At the same time, the children are positioned as the more mature observers of war. By viewing these building conflicts and their aftermath as they were experienced by children, we are given a lens that feels more unmediated, is perhaps more truthful; it’s almost as though we were actually there, as though we went back ourselves.

As surprising as it may seem, it’s easy to forget that the children in Chim’s photographs are young. In his photographs, children look more like adults who have been stripped of their size and societal role—pushed into new occupations, relationships, new ill-fitting clothes. Looking at a photo from Budapest, 1948, that shows a boy wearing a baggy train conductor’s uniform, it took a moment to realize that he was a conductor—of “the Children’s Train,” a railway operated exclusively by young people in Budapest that is still in operation today and began as a USSR initiative to train children for occupations. Elsewhere in the exhibition, a shirtless boy is working, pulling down the lever of a printing press, stretching the sinews of little muscles in his arms, smeared with ink stains like war paint. In another photo, a couple of shabbily dressed preteen boys smoke proudly in public, slumped against a dirty wall. And in a refugee camp, a girl poses in a woman’s corset that hangs off her despite her efforts to close it around her small frame.

And yet, by playing against the detritus of war, don’t these children—as photographic subjects—insist upon their innocence?

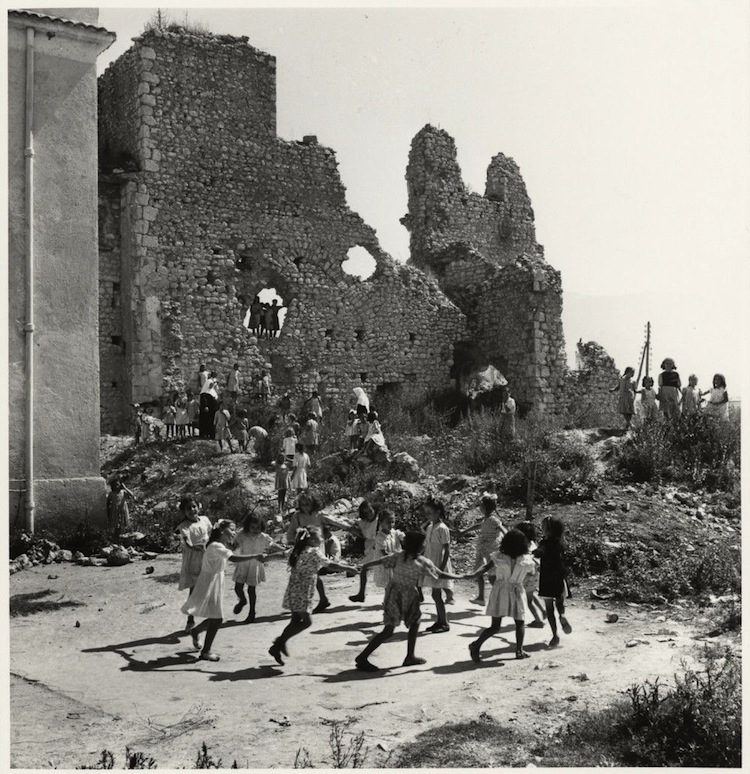

While these children may look and act like adults, the exhibition emphasizes youth with interspersed images of other children at play, displayed in clusters on the gallery walls. The photographs of play lend themselves to the idea that despite all the children have already had to deal with, they are still distinct from adults—they are still, amazingly, innocent. They seem more vulnerable, and sometimes unaware of the crises of their time altogether. And yet, by playing against the detritus of war, don’t these children—as photographic subjects—insist upon their innocence? A very adult thing to do. This is part of the power that Chim gives them.

In these more rare occasions when we see Chim’s children playing, their playtime is perpetually overshadowed by the more serious game of war. In a photograph from 1939, taken on-board a boat carrying Spanish refugees to Mexico, a young boy enacts a micro fantasy of the larger game that’s become his reality: he pushes a toy tank along the deck, an airplane with its nozzle pointing to the sky clutched in his other hand. Meanwhile, in a photo taken in Berlin, 1947, a barefoot boy in dungarees carts his toddler sister through a cobbled street in a makeshift wagon. The boy has stopped in front of the Brandenburg Gate, with his back to us, distracted by the dilapidated monument with its stone peeled away in places and its top crumbling and disfigured. The wrecked monument may be a surprising sight for the viewer, but it has become a part of the landscape of this boy’s childhood.

Considering these photos, I remembered the words of a Palestinian child in James Longley’s documentary, The Gaza Strip. “You want to play at a time like this?” the child says gruffly, reprimanding a younger friend who has found a stick to play with. Holding the boy’s question up to Chim’s pictures of children playing amid the debris of war, they seem to reply: What other time is there? Watching Longley’s film, I was so accustomed to the sight of these children throwing stones across the border and running from Israeli gunfire, that I was startled to find them playing a game of tag. In the same way, I was taken aback by one of Chim’s photographs in which a group of children are seen goofily dangling from a structure meant to keep them off the ruins.

Though this girl has escaped, she hasn’t landed in Narnia or Neverland or Alice’s wonderland, but in a refugee camp—a halfway hiding-place, the nowhere in the middle.

The exhibition’s most arresting photograph—one of the few developed in color—shows an epitomic scene of childhood: a trio of nappy-wearing toddlers on Omaha Beach in Normandy, building sandcastles the same shade as the ringlets of their hair. In the sea behind them lurks a hefty, floating tanker leftover from the war, but the children play blithely in its shadow. Beneath this print, a glass-top display case holds a copy of This Week with the same photograph on its cover (the same issue from 1947 that printed Chim’s series, “We Went Back”). Except the magazine version shows the object in the water reversed, “to create a strong diagonal to the right leading the reader into the magazine,” an accompanying caption suggests. Though I wasn’t surprised by such corruption of an image—the manipulated dramaturgy of the scene—the object in the water became a Loch Ness monster encroaching upon these children in a way that it wasn’t before; it was a sickening sensationalization. A beautiful photograph, a capsule of history, had been modified to sell magazines. Looked at together, the enhanced image and prototype prompted me to think of a painting from a decade before: Dalí’s “Metamorphosis of Narcissus.” Chim’s photo not only looks more like a glossy painting than a photograph; the two versions positioned together expose national vainglory—the way the Allied Forces wished to look upon themselves as fairy tale heroes in the aftermath of a disaster—obsessed, like Narcissus, with its image in the water.

As this image is edited, it’s important to remember that an adult moderated Chim’s photos of children. Observe the stifled pose of a girl photographed in a refugee center in Barcelona, 1936. The child perches on a bed clutching two blonde-haired, thin-lipped wax dolls, nearly bigger than their owner. In her pretty polka-dot skirt, and her curled dark hair falling from a drooping ribbon sitting atop her head, the girl looks like a doll herself. She also looks uncomfortable, as though she doesn’t want to be there; she’s distracted by something outside of the frame—probably the adult who has confined her, against her will, in front of the camera. Looking longer at the picture, I kept returning to the little girl’s eyes, moist under a pair of crumpled eyebrows. They have a lost, dreamy look in them, similar to the one that children sometimes have when they’re being read stories, awash with the dream of entering the phantasmagoric worlds from their pages. Though this girl has escaped, she hasn’t landed in Narnia or Neverland or Alice’s wonderland, but in a refugee camp—a halfway hiding-place, the nowhere in the middle. The photo hanging above, taken in the same refugee center, depicts a young woman sitting similarly adrift on a bed that might as well be a boat. This lady has improvised a desk to write a letter on her suitcase, upon which rests a folded note and a few crumpled balls of paper that suggest she’s having trouble writing. But the resolute look on the woman’s face, the narrow squint of her eyes at the page before her, tell us she has something to say. Maybe she’s trying to put into words whatever the girl is looking for; her wordlessness, the vision in the other’s eyes.

As I walked through the remainder of the exhibition, the far-away look in the little girl’s eyes stayed with me. It also reminded me of another child’s stare. Revisiting an earlier photograph in the show, from Madrid, 1936, of a boy wearing a soldier’s cap and a gun slung over his woolen jumper, I was struck by the vulnerability in his brown eyes. They were pointed straight at the camera as though challenging it, almost in a furtive smile, but they remained glassy, sad. Perhaps the boy was looking at his future, in the frame next to him: a young soldier, donning more official garb, and a better gun with a flag on its end. The soldier’s peremptory stance—shoulders back, chin up, thumb strumming the strap of his weapon—gives the image of a man ready for combat, infinitely more confident than the amateur. But look harder, past the knowing side-glance the soldier throws at the camera, and into the glinting circles of his eyes; you’ll detect a fear there. One can almost see the boy inside.

Chloe Pantazi is a freelance writer, and a graduate student at NYU’s Cultural Reporting and Criticism program. Her writing has appeared on Flavorwire, Hyperallergic, The Atlantic and The Paris Review. She lives in Brooklyn via the UK, and you can find her on Twitter.