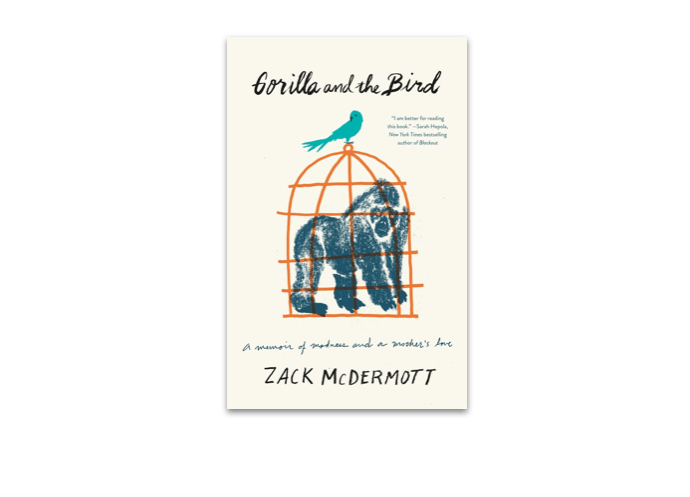

One fateful afternoon, when he was twenty-six, author Zack McDermott left his East Village apartment convinced he was being filmed for a Truman-esque reality TV show. “I knew the people on the sidewalk were actors,” McDermott says at the outset of his debut memoir, Gorilla and the Bird. “Even the homeless people were a little too attractive.” It’s not until McDermott ends up shirtless, sobbing, and arrested on the L train platform that his sharp irony is beveled by urgency and vulnerability. At that point (the end of the first chapter), McDermott is brought to Bellevue’s psychiatric ward, where he is diagnosed with bipolar I disorder following this manic episode—his first. “Regaining sanity at a mental hospital is like treating a migraine at a rave,” McDermott recalls with characteristic humor.

While books like Elizabeth Wurtzel’s Prozac Nation catalyzed widespread buzz about the literary and social value of the mental health memoir as early as 1994 (some might say Sylvia Plath’s 1963 autobiographical novel The Bell Jar is the first exemplar of this), the genre has gained momentum as barriers to marginalized voices have begun to lessen. While New York’s Walter Kirn got away with calling Wurtzel’s memoir “a work of singular self-absorption” in 1994, contemporary titles like Roxane Gay’s Hunger: A Memoir of (My) Body and Daphne Merkin’s This Close to Happy: A Reckoning with Depression have been celebrated for their unvarnished and idiosyncratic meditations about mental illness. Gay’s book offers a piercingly intimate account of her very specific experiences with sexual assault, PTSD, and overeating, writing that she has spent her life trying to feed “a hunger that could never be satisfied—the hunger to stop hurting.” Merkin deploys her dark sense of humor to help ease the reader toward understanding her own “reckoning” with depression. “Despair is always described as dull,” Merkin writes, “when the truth is that despair has a light all its own, a lunar glow, the color of mottled silver.” Gay and Merkin’s works are, indeed, almost entirely self-referential, but they share an outward-looking inclination to educate and include the reader, and find clarity in lyrical storytelling. In his own way, McDermott, too, invites the reader to relate to him and his experiences navigating mental illness (no matter how extreme), and not to take in his story as a voyeur. “Going back on Depakote introduced a level of constipation I’d never known existed,” McDermott writes unglamorously, describing a later hospitalization episode, this time back in his hometown of Wichita, Kansas.

Although McDermott’s book makes light of mental illness more than do the solemn and excruciatingly honest works of Gay and Merkin, all three authors share a staunch resistance to shame, a traditional accompaniment to the disclosure of mental health issues. “It was as though I fell off the end of the earth the minute I wasn’t in the presence of another person,” Merkin writes of her clinical depression in This Close to Happy. It is a condition that leaves her perpetually “shorn of relief.” As Mary McCarthy noted in her review of Merkin’s first book, Enchantment, “the book fascinates one by its openness” and “lack of shame.” In a similar fashion, Gay tells her story without the cushion of apology: “When I was twelve years old I was raped and then I ate and ate and ate to build my body into a fortress.” McDermott, too, is shameless in his writing about illness. In the book’s opening scene, when he recalls “seeing” Daniel Day-Lewis “power-walking…dressed in full Gangs of New York regalia,” his self-assurance is deliberately seductive, letting us see just how sharp the contours of delusion can feel in a state of mania. The oscillation between reality and fiction that McDermott enables us to experience in the book’s opening chapter is a necessary and clever contribution to the mental health literary canon, providing greater immediacy and emotional charge to the portrayal of bipolar disorder.

Those of us who grew up curating our self-presentations on platforms like AOL, Friendster, Myspace, and, eventually, Facebook, were raised to believe, as sociologist Sherry Turkle has suggested, that there is only “one identity that counts”: our identity online. Yet even though social media culture encourages us to prioritize the performance of selfhood online, we’re still not given a hospitable platform to make revealing claims about our lives and identities—and certainly not about mental illness, which remains a deeply stigmatized topic in the US and beyond.

Most studies on social media indicate that it has negative effects on mental health. In one of the most widely cited studies about Facebook usage, depression, and anxiety, researchers found that Facebook encourages comparison and competition with others, often leading to acute symptoms of diagnosable clinical depression. When using Facebook and other forms of social media, most of us are primarily concerned with validation from others—not providing honest disclosures of what our lives are really like. While mental health memoirs are not as digestible as Facebook posts or tweets, they provide an alternative framework for what sharing can look like. They suggest a vocabulary for talking about mental illness and other life challenges—the stuff most of us aren’t inclined to share in a dogged attempt to rack up likes—that is both honest and destigmatizing.

Still, McDermott’s memoir has certain blind spots. As Andrew Solomon aptly wrote in his review of Merkin’s This Close to Happy, “Most memoirs aim to seduce.” It sometimes feels like McDermott is trying too hard to impress us through his cool and amicable narrator. McDermott’s chattiness, biting humor, and tender self-deprecation certainly bring a powerful voice to the broader cultural discussion around mental illness. But sometimes his irreverence feels forced, as when he says that, “Depression felt as much a luxury as veganism and fair trade coffee.”

There are not many books out there about the mystifying illness that is bipolar disorder, and for that alone, Gorilla and the Bird is a welcome addition to the collection of mental health memoirs. Unlike Jamie Lowe’s Mental: Lithium, Love, and Losing My Mind (published in the same week as Gorilla and the Bird), McDermott’s book is not trying to be an expansive and encyclopedic account of bipolar disorder. Refreshingly, McDermott seems most interested in exploring the effects of his illness on his relationships, notably with his mother (whom he calls the Bird because of “her tendency to move her head in these choppy semicircles when her feathers were ruffled”). This interest is partially what makes the book such an original contribution to its genre. That said, McDermott’s choice to conclude his memoir with the story of meeting his wife felt aspirationally Hollywood—a bit too neat and stylistically incongruent with McDermott’s apparent distaste for sentimentality.

Then again, it was just announced that Channing Tatum optioned the book for TV. What typified the author’s first descent into delusion now marks a milestone for his success. While Gorilla and the Bird may have flexed its entertainment muscles a bit too eagerly for my taste, McDermott’s accessibility as a storyteller is a radical feat for destigmatizing mental illness.