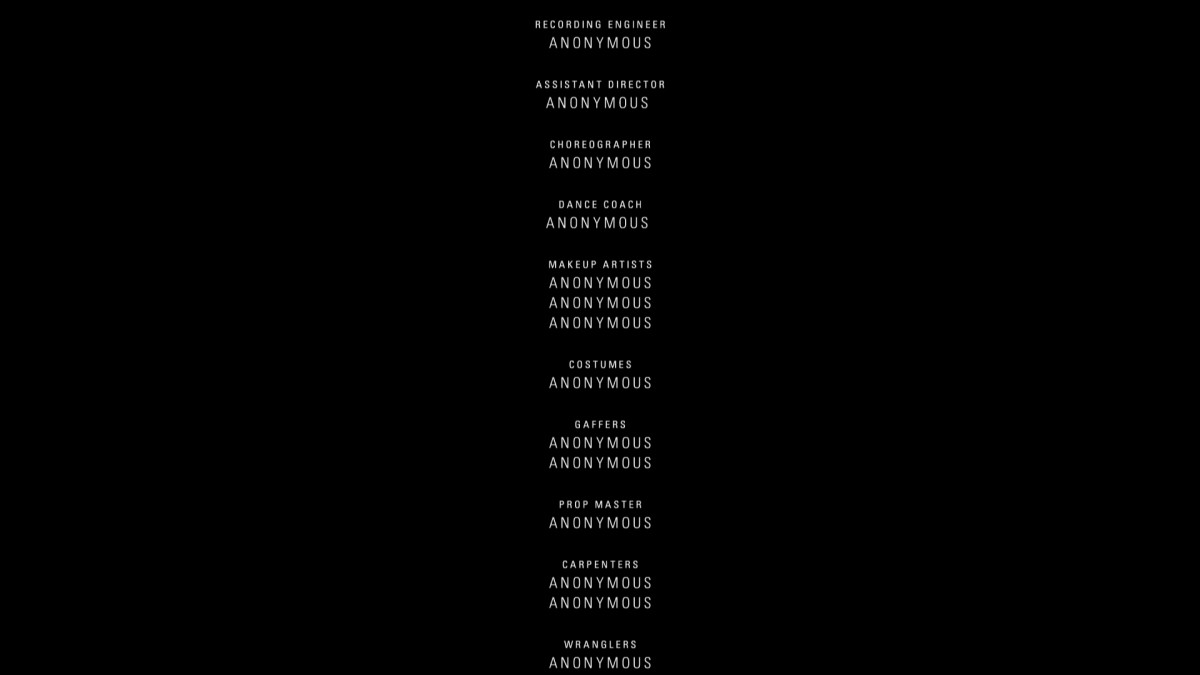

One of the most haunting aspects of the director’s cut of The Act of Killing, a new documentary on the perpetrators of Indonesia’s 1965-66 anti-communist genocide, comes during the credits. As they roll, the word “Anonymous” begins to appear—sporadically at first. Then, suddenly, it’s all you see.

The anonymous members of the film crew are Indonesians, people who have chosen to go unnamed for fear of reprisal in a country that has never fully acknowledged the estimated one million murders that helped sweep General Suharto to power for thirty-one years. The North American premiere of The Act of Killing’s director’s cut played to packed audiences at Lincoln Center’s New Directors/New Films in March, and the film has since racked up top awards at Documenta Madrid, the Berlin International Film Festival, and the Toronto International Film Festival, among others.

But in Indonesia, where the current government has direct ties to the massacres, only carefully vetted audience members at underground screenings are able to see the film.

Indonesian history books and government-backed narratives continue to explain the 1960s purges in terms of defense and national sovereignty. Until Suharto’s 1998 fall, the state’s own bloody, slasher-style propaganda film, Pengkhianatan G30S/PKI, reinforced the idea that the nation was saved from communist terror. Indonesian schoolchildren under Suharto’s New Order regime were forced to see that film at least once per year.

“It is not particularly good or convincing acting,” recalled Indonesian journalist Dina Indrasafitri. “But imagine being seven years old seeing that movie. And seeing it every year afterward. That is a pretty early introduction to bloody scenes and propaganda.”

In the years since Suharto’s fall, Indonesia has made strides to establish rule of law, reform its financial systems, and achieve development goals. The country’s post-Suharto transition to democracy has allowed for greater scope of expression, even as shadowy forms of coercion persist.

“The real leaders—the real power brokers in Indonesian society—are continuous.”

But Indonesia has been far slower to reckon with the earlier period of tremendous violence. “The reason for the inaction is that [current] President [Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono’s] father-in-law, Sarwo Edhie Wibowo, was responsible for initiating the killing,” Professor Adrian Vickers, a University of Sydney expert on modern Indonesian history, wrote in an email. “So he’s unlikely to do much.”

A number of recently released books, articles, and movies on the killings are helping to turn this tide of historical amnesia, and The Act of Killing is among the most powerful yet. The film follows two North Sumatran men—movie-ticket-scalpers-turned-thug-killers—as they explain, justify, and ultimately reenact their actions with the help of elaborate sets, fake blood, and spools of wire. “Don’t think too much about it,” Herman, a supporter of one of the killers, advises during a shoot.

Yet the meticulous efforts of the killers featured in the film—to get their reenactments just right, to get the correct level of struggle from their actor-victims, to stage elaborate forgiveness ceremonies—suggest that “think about it” is pretty much all some of them have done ever since.

“The film emphasizes [the current government’s] continuity with the New Order, with the military dictatorship, because basically the real leaders—the real power brokers in Indonesian society—are continuous,” commented director Joshua Oppenheimer. “[The current leaders] are the protégés of the perpetrators.” Oppenheimer shares The Act of Killing directing credit with Christine Cynn and an Indonesian who goes by Anonymous.

Seeing the film in Indonesia means landing on a carefully researched list, submitting to airport-style security checks, and in some cases allowing the courier to wait to take the DVD back as soon as the film is finished.

What happened to Indonesia’s suspected communists in the mid-1960s remains unresolved, obscured, and potentially dangerous to confront. Since The Act of Killing first began to circulate in Indonesia in September, private screenings and secretly couriered DVDs have helped to ensure the safety of viewers and organizers alike.

“As you can see in the film, anyone with power can use thugs or whoever to do bad things,” the anonymous co-director wrote via email. “We simply don’t know what might happen to us if we reveal our identity. Somehow I feel that unknown risk is much more worrying than a real threat.”

Managing that unknown risk has become the job of a network of local writers, academics, journalists, and activists, who share copies and stage underground screenings notable for their extremely tight security. The private screenings reach anywhere from just a few viewers to a few hundred. Seeing the film in Indonesia means landing on a carefully researched list, submitting to airport-style security checks, and in some cases allowing the courier to wait to take the DVD back as soon as the film is finished.

Screening hosts, first vetted by The Act of Killing crew, conduct their own check on potential audience members. So far, no one has been turned away and screenings have remained peaceful. But the process is rigorous. Bali-based filmmaker Daniel Ziv, a screening organizer and early viewer of the film, explained via email how it works:

I went through three layers of vetting before receiving details of where and when the screening would be held. First, I was recommended to the [The Act of Killing] producers by a mutual friend—a senior journalist in Jakarta… Then, I received an email from an anonymous account asking me to confirm my identity. I did so, and the next day I received another email informing me that a screening will be held in a week, and that I will be invited, but must await details coming from an additional email. Eventually they sent me the information, and we were urged not to share it with anyone, and also not to broadcast anything about the screening or the film on social media until after the event was over.

To date, the biggest number of simultaneous, private screenings in Indonesia occurred on December 10, 2012, International Human Rights Day, when an estimated fifty clandestine screenings in thirty cities took place. Oppenheimer estimates that, as of April, roughly three hundred covert screenings have happened in ninety-three Indonesian cities reaching up to fifteen thousand Indonesians.

“That’s not a huge number in a country like Indonesia,” he said. “But the film is like the kid in the emperor’s new clothes, pointing at the king and saying look, the king is naked. Everyone knew the king is naked but was too afraid to say so.”

Oppenheimer expects The Act of Killing will be banned by the country’s censorship board, to which he will have to submit the film to get it into Indonesian theaters. Although the country has fairly robust laws protecting freedom of print and online media, film censors continue to monitor what is shown in the theaters.

“If they ban the film, that will be a litmus test as to whether the government has any real commitment to ending impunity and to freedom of expression,” Oppenheimer said.

If the film is banned, Oppenheimer plans to upload it to the Internet so that it can be freely viewed. “We will encourage it being pirated,” he said. The film will be submitted to the censorship board following its global theatrical run.

It is unclear if the peaceful response to the film to date is due to the great precautions organizers continue to take in staging screenings or an increased readiness in Indonesia to examine this period of history.

For now, covert screenings of The Act of Killing remain the norm in Indonesia. The screening Ziv organized in Bali—among those to happen on December 10—had one hundred eighty-five viewers, including children and grandchildren of victims and survivors of the genocide. Afterward, Oppenheimer joined a discussion of the film via Skype.

Oppenheimer has steered clear of Indonesia since completing the documentary but regularly takes questions and comments from Indonesian audiences remotely. “I think I could go back,” he said. “But I couldn’t get out. And I don’t know if that means I’d be killed or if it means I’d be arrested and in some sort of protective custody and charged with all sorts of crimes. I just think I can’t go.”

While there has been no known violence against members of the film crew or screening hosts, Oppenheimer says he has received some threats, including a Twitter message saying, “It’s lucky that the director of The Act of Killing is not someone who lives permanently in Indonesia because if he did the title would change to The Act of Being Killed.” In March, Oppenheimer expressed concern for his own safety ahead of a trip to Hong Kong and when showing the film in the Hague to “a lot of Indonesians.”

It is unclear if the peaceful response to the film to date is due to the great precautions organizers continue to take in staging screenings or an increased readiness in Indonesia to examine this period of history. “While there’s no direct threat to us so far, that doesn’t mean all Anonymouses are safe,” the anonymous co-director wrote in an email.

The killers profiled in the documentary have also been on guard. The broader attention the film has received in Indonesia—including a massive spread by Tempo, the country’s most prestigious newsweekly—has rattled them. Anwar Congo, whose personal anguish over the memories of his thousands of murders is at the center of The Act of Killing, held a press conference to say he was tricked and that the film he was told he was making was not what is now airing at international festivals and secret screenings.

“We know that it’s not true but we understand he has to hold that position for his own security concerns,” co-director Anonymous said. “After several hectic weeks with journalists, Anwar can be said to now live a ‘normal’ life again. He’s still good with his friends. But he refuses to make any recorded statements.”

Anonymous is quick to stress that prosecution of the small-time thugs who did the dirty work of the genocide should not be the focus of any national strategy to face this history.

“Should there be any court hearings about the 1965-66 mass violence [they] should be about the people who are in the top chain of command, the people who are still spreading terror… for their own benefit,” the co-director said.

In 2004, Indonesia held its first-ever direct presidential election. The resulting democracy is still being tested and Anonymous and others agree it is unlikely what happened in 1965-66 will find an objective government audience anytime soon, and certainly not under the current leadership.

“The Attorney General has said that there’s no evidence that the mass killing is a human rights violation,” Anonymous said. Indonesia’s next presidential election will take place in 2014.

With official inquiry perhaps a long way off, Anonymous said the conversations now getting underway are what have made The Act of Killing worth its risks:

The Act of Killing is a success when it is discussed, when it changes the way people see their country, their history, and in the end their identities. When people realize that the past is not merely the past, that there’s a wound [that was] created in the past. It hasn’t healed and something needs to be done about it.

Many Indonesians agree. “As long as people are still ‘anonymous’ on credits, as long as these screenings remain underground and secretive, as long as there is still fear when this subject matter surfaces,” commented Jakarta-based filmmaker Rayya Makarim, “we are far from change.”

The Act of Killing will be featured in the Human Rights Watch Film Festival in New York on June 18 and 19 and released in the United States on July 19. Viewers in Indonesia are seeing the longer, director’s cut of the film.