In Afghanistan, the U.S. military disposes of garbage—computers, motorbikes, TVs, shoes, even human feces—in open burn pits. Are toxic clouds from these sites making everyone sick?

Photograph courtesy of the author

Shopkeepers close their doors when U.S. troops patrol Bagram Village just outside the American base of the same name.

Their shelves hold Army pants, boots and knives sold to them, they say, by Afghans working on the base, gifts to them from American soldiers but more likely stolen. Either way, soldiers confiscate these items on sight. The shopkeepers sit in the shade watching traffic inch past, motorcycles weaving between cars. They hear the saws and hammers from nearby construction. They watch steam rise from restaurant kitchens.

Sipping tea, the shopkeepers wait for my questions while keeping a wary eye on the passing soldiers. What is it like living so close to an American base? I want to know. I expect them to grumble about the soldiers searching their shops. Instead, they tell me about a strange odor they say comes from the base. It smells of plastic.

****

The odor, the Afghans said, comes from a burn pit, a huge open dump site used on U.S. bases to consume mountains of trash, unleashing harmful chemicals. Burning plastic, for instance, releases carcinogenic substances that may increase the risk of heart disease and respiratory ailments, cause rashes and damage the nervous system.

Computers, television sets and mobile phones release cadmium, lead, and mercury, which can also damage the nervous system and the kidneys.

As of last year, the United States Central Command estimates that there were 114 open burn pits in Afghanistan. According to a public information officer at Bagram Airbase who asked not to be identified, there were twenty-two burn pits in Iraq as of 2010. Used since the beginning of both wars, burn pits have consumed metals, Styrofoam, human waste, electronics and even, in some cases, vehicles and body parts. Diesel and jet fuel keep the pits burning, adding their own mix of dangerous elements.

There are more than 100,000 troops currently deployed in Afghanistan—and thousands more private contractors—and the Department of Defense estimates that each soldier and contractor generates about ten pounds of solid waste per day.

Military officials declined to comment on the decision to use open burn pits, but the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency bans open pit burning of materials that discharge toxic chemicals and whose smoke can contribute to the risk of cancer, asthma and reproductive problems. The EPA also prohibits open pit burning grass and leaves, food and petroleum products such as plastic, rubber and asphalt.

In Afghanistan and Iraq the expediency of burning trash trumps environmental and health concerns. In a memo dated December 20, 2006, Bioenvironmental Engineering Flight Commander and Air Force Lieutenant Colonel Darrin L. Curtis warned of acute and chronic health risks posed by the Balad Airbase burn pit in Iraq.

Whether through a lack of forethought, a desire for expediency, or the logistical demands of the battlefield, the military chose burn pits as its means to destroy trash. And there is a lot of it. There are more than 100,000 troops currently deployed in Afghanistan—and thousands more private contractors—and the Department of Defense (DoD) estimates that each soldier and contractor generates about ten pounds of solid waste per day.

Veterans Administration and private physicians have seen a significant increase in respiratory problems in soldiers returning from Iraq and Afghanistan. Other physical problems among war veterans include shortness of breath, headaches and coughing up blood. Almost all of these soldiers had exposure to burn pits as well as battlefield smoke and dust storms. It seems unlikely that the thousands of Iraqis and Afghans working on U.S. military bases or living nearby have escaped such debilitating ailments themselves.

“If we know American soldiers are being affected, then we know it is quite possible for local laborers on bases and the local population to be affected,” said Steven Markowitz, a physician and professor of environmental sciences at Queens College, City University of New York.

U.S. soldiers have medical coverage through the Veterans Administration. Afghan and Iraqi troops and civilians, however, must rely on healthcare systems gutted by war. For them, exposure to burn pits could be dire. But no one knows. No medical studies have been conducted on them.

I decided to see burn pits for myself and hear what American soldiers and Afghans had to say about them.

Before leaving for Kabul, I called the Pentagon and Department of Defense and asked to speak with a health official about burn pits. My calls were not returned. I asked if I could speak with an American military doctor on Bagram Airbase. The request was denied.

I didn’t mention burn pits in the embed application. Instead, I asked to profile the lives of soldiers, including the health issues they face. My application was approved.

I managed to reach Captain Patrick Laraby, director for environmental and occupational medicine at the Navy Bureau of Medicine and Surgery in Washington DC. “One can imagine breathing burning smoke is not healthy,” he said. “To remediate that, in larger garrisons we put in closed incinerators.”

That’s not entirely accurate. Military spokesman Major T.G. Taylor said that as of January 2011, there were thirty-three operating incinerators on eleven bases, still far fewer than the number of open pits in use; I discovered that two of the largest bases in Afghanistan, Bagram Airbase, about an hour’s drive outside Kabul, and Kandahar Airbase in the south, continue to use burn pits. (Taylor said that as of January, more than 150 additional incinerators were on order or waiting to be installed.)

“Yes, there is a burn pit here,” an Afghan translator for U.S. forces said about Kandahar when I spoke to him by phone. “I see it every day. It burns twenty-four hours a day. Some people in villages complain about the smell. Afghan National Army families live near it. They cough, complain of headaches and sore throats.”

To see and experience a burn pit firsthand, I would have to embed with the Army. Based on my unreturned calls to the Pentagon and Department of Defense, cooperation with the military seemed unlikely. I didn’t mention burn pits in the embed application. Instead, I asked to profile the lives of soldiers, including the health issues they face. My application was approved.

My Afghan colleague Haji Aziz Ahmad picked me up at the airport when I arrived in late June. In traffic it would take an hour to reach my hotel. I decided to get on with my appointments and deal with the hotel later.

We inched our way toward the office of Aziz’s brother, Dr. Farid Homayoun, a pediatrician and the director of the Afghan branch of the British de-mining organization HALO Trust. After more than thirty years of war, Afghanistan is one of the most heavily mined countries in the world. I wanted to know if Dr. Farid, as everyone calls him, had seen any patients who had been exposed to burn pits.

Earlier in the year, Dr. Farid had been kidnapped. A car pulled in front of him when he left his clinic one evening and he was taken hostage at gunpoint. Aziz received a phone call from a pharmacist who witnessed the abduction. Frantic, Aziz tried calling Farid but his hands shook and he was unable to dial his cell phone. His wife asked him what the problem was.

“Let me alone, let me alone!” Aziz shouted at her.

Motivated only by money, the kidnappers demanded a $5 million ransom. The family talked them down to $400,000, which they borrowed from a bank. Now the bank owns everything that once belonged to Dr. Farid, Aziz and the rest of the family.

“Security is terrible,” Aziz says. “Any time now an explosion can happen, two, four, six in the morning. Sometimes at ten o’clock at night. Two days ago, sixty people including some doctors were killed when a bomb exploded outside a hospital in Logar Province. Yesterday, two men driving a bank truck were killed and robbed of $4 million.”

In the coming days, eighteen people would die in a suicide attack on the Hotel Inter-Continental, one of Kabul’s swankiest resorts. President Hamid Karzai’s powerful half-brother would be assassinated and two of the president’s own aides would be shot to death in their homes.

No wonder Aziz turned to me, as he maneuvered through traffic, and said, “You came here to write about trash?”

Trash is an everyday part of life throughout Afghanistan. Garbage-filled gutters give off awful odors. Horses and donkeys defecate on chaotic streets. Container trucks dump waste into streams and farm fields under the mistaken notion that the waste can be safely used as fertilizer. In the absence of public toilets, people squat in storefront corners to relieve themselves. Without a strong breeze, pollutants emitted by aged cars, diesel-fueled trucks, brick factories, and other coal-burning industries stain the air of Afghanistan’s major cities gray for days at a time.

Miller has seen more than 100 soldiers with shortness of breath after service in Iraq and Afghanistan and has diagnosed multiple patients with constrictive bronchiolitis, almost all of whom had been subjected to smoke from burn pits.

Scattered throughout Afghanistan, the U.S. military’s burn pits have added their own unique mix to the pollution, in blatant contravention of environmental laws the U.S. applies to itself.

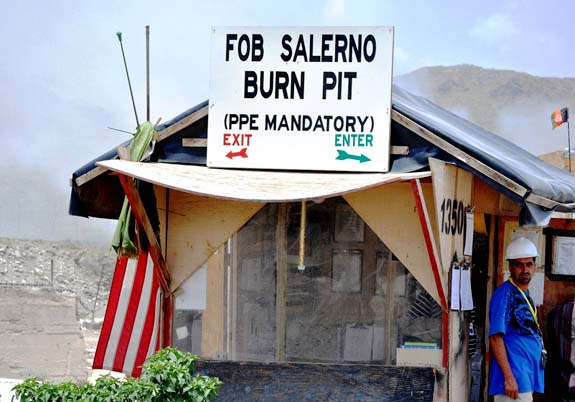

A lawsuit filed last year in the U.S. by Burke PLLC and later joined by Motley Rice Attorneys at Law, one of the nation’s largest plaintiffs’ litigation firms, contends that Kellogg Brown and Root (KBR) and its former parent company, the military contractor Halliburton, exposed servicemen and women and civilian contractors to huge quantities of toxic dust, fumes and other air pollutants by unsafely burning garbage in burn pits. The litigation mentioned burn pits at Bagram Airbase, Forward Operating Base Salerno, Kandahar Airbase, and many others in Afghanistan and Iraq.

“My sense is that something over there is causing problems with shortness of breath, asthma, constrictive bronchiolitis,” Dr. Robert Miller, assistant professor of allergy, pulmonary and critical care medicine at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, said in a telephone interview.

Miller has seen more than 100 soldiers with shortness of breath after service in Iraq and Afghanistan and has diagnosed multiple patients with constrictive bronchiolitis, almost all of whom had been subjected to smoke from burn pits. “Burn pits,” he said, “are clearly toxic.”

Miller’s findings regarding a link between constrictive bronchiolitis and burn pit toxins were removed in April 2010 from the training letter that the Department of Veterans Affairs distributed to address environmental hazards in Iraq, Afghanistan, and other military locations. When asked about the number of Afghan vets with respiratory illnesses, Major Taylor responded by citing a May 2010 DoD study which he says found that illnesses possibly due to smoke exposure were no more common thirty-six months after deployment among those who were exposed to burn pits than in those who were not. He added that the “DoD continues to examine the evidence.”

An October 2010 Government Accountability Office report states: “Despite its reliance on burn pits… CENTCOM did not issue comprehensive burn pit guidance until 2009.” The report’s authors found that at four burn pit sites in Iraq (GAO researchers did not visit burn pits in Afghanistan), operators were not restricting the burning of plastic and other material that produced harmful emissions.

“Sometimes the smoke covered the base when the wind blew. The village people complained about the smell. They said their children were crying.”

In April 2010, the Veterans Administration issued a memo regarding “environmental hazards in Iraq, Afghanistan, and other military installations.” Sent to regional VA offices in the U.S., the memo lists harmful chemicals released during the incomplete burning of coal, oil, gas, and garbage.

“There are a lot of unknowns,” said Dr. Terry Walters, director of the Environmental Agents Service of the VA Office of Public Health and Environmental Hazards. “What we do know, some returning vets have symptoms like asthma. The concern, [does a burn pit] cause long-term chronic disease? Does it cause cancers? Does it impact longevity of the veteran? I don’t know what to tell you.”

I worked with American forces in Bagram in 2008.

I worked in a store distributing uniforms. The uniforms were on a shelf. An American soldier would bring in a request—one pair of this, two pair of that—and I would take whatever they needed from the shelf and give to the soldier.

The burn pit was at the far end of the base. It was very deep. I can’t say how big. Like three soccer fields. They used a bulldozer and just moved everything into the pit. The fire was twenty-four hours running. The fire never stopped. The garbage was in plastic bags. I saw these things burned: old shoes, water bottles, computers, televisions, keyboards. Vehicles carried the garbage. Bulldozers pushed it in. It smelled very badly. Sometimes the smoke covered the base when the wind blew. The village people complained about the smell. They said their children were crying.

—Gulam Raza, shopkeeper, Bagram Village

Aziz and I arrived at Dr. Farid’s HALO Trust office after a painstaking hour-long drive. Maps tacked on the walls indicated areas of Afghanistan still littered with mines.

“Why would someone take a job near a burn pit?” Dr. Farid asked as he served tea. “You need to understand, people are poor, desperate. If they work around burn pits, they consider themselves lucky.”

When Hamid Karzai’s new interim government was installed in 2001, Dr. Farid continued, Karzai issued a decree for agencies like HALO Trust to destroy ammonium nitrate, used in the manufacture of roadside bombs. But destroying the chemical was easier said than done. Burning it released toxins. Burying it contaminated underground water sources. Whatever they tried, the land suffered. The same, he says, is true of the military’s vast supply of trash. The burn pits, however, produce the worst sort of pollution.

“But who cares about the environment in a war zone?” Dr. Farid said.

In 2007, the Karzai government enacted the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Environment Law, which asserts in part that “no person may discharge or cause or permit the discharge of a pollutant into the environment, whether land, air or water, if that discharge causes, or is likely to cause, a significant adverse effect on the environment or human health.”

The legislation, however, does not apply to U.S. and coalition forces. Afghanistan’s investigators do not have authorization to inspect their bases. And nationwide, enforcement of the law has been relegated to the grossly understaffed National Environmental Protection Agency of Afghanistan, rendering the law virtually meaningless.

As far as Dr. Farid was concerned, it was too late for environmental officers to do anything about burn pits, even if the government could inspect them. Too many Afghans, he said, have worked on coalition bases. It was difficult to determine who had been exposed to toxic smoke. (U.S. military officials declined to provide an estimate of how many local contractors had worked on bases with burn pits.)

“Nobody cares in Afghanistan. That’s the problem,” Dr. Farid said. “You may have heard I was kidnapped. I am an example that all anyone thinks about is, ‘How can I make money?’ Every day is hand to mouth. No one thinks as a nation.”

“We are a very low-level government agency,” Hussaini said. “A lot of other national issues are considered more important.”

Even if Afghans thought as one nation, the healthcare problems would remain daunting. Afghan medical facilities lack the equipment, and most of its doctors don’t have the training for the proper diagnosis of many chronic or deadly diseases.

“There is no treatment for cancer here,” Dr. Farid said. “We lack basic medical infrastructure. A doctor would not know what was really wrong until the problem was well advanced and then what? There’s not much you can do except enjoy the time you have left and write a will.”

From Dr. Farid’s office, Aziz and I drove to the nearby Ministry of Health. There we were shown to the office of Amanullah Hussaini, the environmental health director. Like the director of National Environmental Protection Agency of Afghanistan, he said he could do nothing about the burn pits.

“We are a very low-level government agency,” Hussaini said. “A lot of other national issues are considered more important.”

Hussaini said his nephew, Samiullah Safit, worked as a translator for the U.S. Army and has seen burn pits firsthand. He gave us his cell number.

“I am responsible for this office,” Hussaini said. “It is a shame on me I can’t do anything.”

I left Bagram Airbase just two months ago.

I started there in 2009. I cleared weeds on the base from 8 a.m. to 4 p.m. The burn place, the things I saw thrown in it, were expensive things. Old computers, blankets, TVs, mobile phones, mattresses, pillows, shoes and plastic bottles. Even a motor bike. They used gas to keep it burning. The pit is a place like this [a farm field outside Bagram Village] in size but much bigger [he spreads his arms wide] and very deep. I would get as close to it as you and I are to each other now. Trucks brought the garbage. Americans escorted us to the pit. It smelled, the smoke like a black cloud. The smell was like a hot burning in my throat. American soldiers coughed. I coughed. Later I took medicine. I still cough. A bunch of people living around Bagram have the same problem.

—Tareq Aziz, 20, Barikaaw Village

Twenty-year-old Samiullah Safit greeted Aziz and me outside Kabul’s Academy Technique, a family barracks for members of the Afghan National Army in which Samiullah’s father, a major, serves.

Samiullah quit translating for U.S. troops this year after a roadside bomb exploded near his armored vehicle. He was uninjured but when he told his mother and father, they insisted that he return to Kabul. He obeyed but kept his hair in a buzz cut. He missed army life.

At an open dump site that lay about a block from the Academy, Kuchi nomads sort through bags of discarded food to feed their goats. They also scavenge for cans and plastics to sell as scrap. Torn plastic bags and other loose trash cling to the barbed wire, which unspools in fat rolls across the tops of the walls enclosing Academy Technique. At night, the stench from the dump drifts through the cracks of loose window frames and fouls the stifling summer air.

“You cannot sleep for the smell,” Samiullah said. “If you come to my house you will see a lot of flies. When my uncle comes here, he leaves after one hour.”

Why risk a well-paying job because of a bad smell?

Samiullah translated for U.S. troops at several combat outposts in Aggandab District, Kandahar Province. The Army, he said, burned human waste and plastic in open pits that blazed constantly. Everybody suffered breathing problems, Afghans and American soldiers alike. Shortness of breath, burning sensations in their chests, everyone seemed to have rashes and other skin problems. The Americans would share their care packages with Samiullah. He noticed they received a lot of skin cream.

One morning, a U.S. Army sergeant told Samiullah to help him pour fuel on bags of human waste. Samiullah refused. “This is your shit,” he said he told the sergeant. Afghan soldiers, Samiullah said, complained to their American counterparts about the pit. “Why do you guys burn shit? We don’t feel good,” they would say. The Afghan National Army would dig holes and bury its trash.

But the Afghans, Samiullah said, never escalated their objections. An Afghan translator earned upwards of $800 a month; Afghan laborers on U.S. military bases brought home $200 a month, soldiers even more. In Afghanistan the average income is less than $50 a month. Why risk a well-paying job because of a bad smell?

I told Samiullah that I was flying to Fort Salerno the next day for an embed. Did he have any advice?

“Avoid roadside bombs,” he said. Then he paused and looked hard at me. He said his breathing had not been the same since he quit his job.

“If you’re around a burn pit,” Samiullah said, “wear a mask.”

In 2007, when I was in the bazaars, one morning I smelled it in Bagram.

I didn’t understand the smell. It smelled of plastic. If you lived here you’d smell the smell. The condition of the air is very bad. I cough now. The cough comes from my chest. My nose, I’m always blowing my nose. During the night I feel bad when I try to breathe. Diesel smoke is black. This other smoke is green-black. I live two kilometers away. If the direction of the wind comes this way then you will smell it.

—Abdul Mubin, 30, Barikaaw Village

After tea with Samiullah, Aziz took me to my hotel. For the next two weeks, Aziz and I drove to Bagram Village almost daily to speak with shopkeepers about the local burn pit.

As my embed date approached, I emailed two U.S. veterans who had served in Afghanistan and shared with them comments several Afghans had made about the burn pits.

Black and brown snot was referred to as ‘the Iraqi or Afghani crud.’

“It sounds like nothing has or did change from 2004,” wrote Derrol Turner. He was stationed at Bagram in 2004 as an Air Force mechanic. “I believe I have even told people that the size of the pit being at least three football fields in size and there were bulldozers there with garbage trucks circling down into the pit and dumping their trash. [Tareq Aziz] is accurate about how it affects you. Just a nasty situation all the way around. Memories, Bagram is where all my troubles began. It’s where I noticed the ‘hard to breathe’ feeling and total stuffiness of my sinus.”

On the morning my embed began, I received a note from the second veteran I had emailed. Because he is still on active duty, he asked me not to reveal his name, where he was stationed, or when he served in Afghanistan.

“The descriptions of the burn pits sound very similar to what I experienced,” he wrote. “The overwhelming smell, for sure is that of burning plastic. Also, what the man said about what was being put in the burn pits is very accurate. Most the time there were large stacks of burnt metal debris stacked very high in areas. You could also sort of tell what they were burning by the color of the smoke.

“I started with just a cough and a feeling of being out of breath when I was around the pits as well, but we were always told that was just your body adjusting to the garbage haze. Including always blowing black and brown snot out of our noses, it was referred to as ‘the Iraqi or Afghani crud.’ When I got home from Afghanistan, I went downhill fast. A lung biopsy showed I had constrictive bronchiolitis.”

I arrived at Fort Salerno toward evening aboard a C-130 military aircraft jammed with soldiers and some contractors. After we landed, I followed the soldiers to a wood-plank building with a wobbly porch that moaned beneath the stomping of boots and tossed off backpacks.

The major responsible for the press office and a lieutenant met me. They said I would be embedded at Combat Outpost Tereyzai, not far from Fort Salerno, the next day.

We waited for the plane to unload a pallet of gear and made small talk. The major said he had served at Balad Airbase in Iraq. I told him I had interviewed veterans who had served at Balad and that they had often mentioned the burn pit there.

“You have a burn pit here?” I asked. I knew the answer of course, but hoped he would show me the pit.

“You can smell it?” he asked.

Early the next morning, I followed a stone path from the makeshift plywood press barracks to a paved road. Fort Salerno is a self-contained community with shops, FedEx, and, in a nod to Afghanistan, even a bazaar. Approximately three thousand American soldiers and contractors live on the base, which means it was generating about thirty thousand pounds of trash daily. I was chasing a gray column of smoke I first saw when I woke up. The burn pit? I didn’t know, but when he dropped me off, the major mentioned that I might be able to see smoke from the pit from my room.

The road curved toward a construction site. Signs with red skulls and cross bones warned of toxic material. An Afghan laborer working on the site told me it belonged to the Turkish construction company Metag, which was building a new burn pit to replace the old one. I asked where that old one was. He pointed toward the rising smoke I had been tracking.

I continued walking past backhoes and stacks of metal beams, piles of dredged earth and a row of portable toilets. A man with long blond hair emerged from a toilet and watched me. I stopped at a sign, overhanging a small shack: “FOB Salerno Burn pit.” Other signs warned of DANGER and urged CAUTION. NO ENTRY BURN IN PROGRESS. Still another read HARD HAT AREA.

The smoke smoldered and drifted and my head felt like it was swelling and my temples began to throb.

“A hard hat is for something falling on your head,” Celeste Monforton, a lecturer in environmental and occupational health at The George Washington University told me later. “If you look at the hazards of a burn pit, would a hard hat be the protective gear you’d pick? Putting someone in a hard hat only gives the impression of safety.”

Monforton said a worker in the U.S. would be required to wear covering such as inflammable clothing and eye protection. If, as in the case of burn pits, there was a risk of exposure to air contaminants, the employer would be required to specify the contaminants and select an appropriate respirator to be worn by workers. In fact Taylor claimed that the DoD requires that such respiratory protection be made available to military personnel involved in burn pit operations.

I saw no such gear on the racks of the shack, only white hard hats. The smoke I had been following rose from what resembled a huge manhole hollowed out in the dirt. I imagined Alice falling down the rabbit hole. Each load of the bulldozer was consumed almost instantly. Scattered plastic bottles and loose trash bags flamed and then melted at the periphery and a bitter, almost metallic odor filled my nostrils. The smoke smoldered and drifted and my head felt like it was swelling and my temples began to throb. Flames leapt from a Dumpster near a trash drop-off site for trucks.

I read a list prohibiting the burning of aerosol cans, compressed gas cylinders, medical waste, metal, ceramics and other non-combustible items, pesticides and batteries but there was no stated prohibition against other harmful items like plastic.

In October 2009, the National Defense Authorization Act barred the burning of some hazardous trash, such as medical waste, in burn pits. But some is not all. Plastic products, to give just one example, make up a significant bulk of the trash on military bases but are not excluded from the burn pits.

The man I saw earlier approached me. He said he was from Texas and had been working in Afghanistan for eighteen months. His long stringy blond hair stuck out beneath a baseball cap. He had on a blue T-shirt, jeans and boots but no protective clothing. The burn pit operated from 6 a.m. to 5 p.m., he said. He had been working for about an hour. The days were long and hot. The trash burned easily except for cafeteria garbage, which was often wet and forced him to add more diesel fuel to the fire.

I watched him drive a bulldozer to the drop-off point and scoop up stuffed plastic trash bags and dump them into the pit. Thin flames darted up from the hole into the gray smoke. The major had told me I could wander the base on my own but if I wanted to take photos, I needed an escort. I returned to my room, got my camera and called the lieutenant who had accompanied the major the night before. Without elaborating, I asked him take me to the burn pit.

“I don’t see any problem with that,” the lieutenant said.

At mid-morning, he and I returned to the pit. Afghan laborers were shoveling in loose trash. None of them wore respirators, or even masks. Gray smoke ballooned out of the hole in heavy clouds. Some of the Afghans covered their faces with scarves, but most simply turned the other way. I took some photos as the lieutenant spoke to the supervisor. The supervisor said we needed permission from Fluor, the Texas-based contractor in charge of the pit, before he could allow us on the site.

At the Fluor office on the base, an office manager told me to contact a spokesman in the States. I looked at my watch. It would have been about 3 a.m. there.

“So much for that,” I told the lieutenant.

“I can see why,” he said. “Burn pits aren’t the most attractive things.”

I did call the Texas office later, but the spokesman referred all questions to the military.

As the lieutenant and I left the Fluor office, the office manager telephoned the burn pit supervisor. He wanted to know what I had asked him. The supervisor told them I had taken some photos.

Moments later, the major called the lieutenant and asked for me.

“You can’t use the pictures of the burn pit, John,” the major said.

He used my first name, instead of the middle name I go by, and for a brief second, I was reminded of my father calling me from my room when I had done something wrong: John Malcolm come down here now!

I told him I understood, but I did not say I would not use the pictures.

“You can’t use the pictures, John,” the major says again and again.

“The lieutenant made a mistake taking you to the burn pit. The pit doesn’t fall under the Army’s jurisdiction. It belongs to a civilian contractor.”

I told him I understood, but I did not say I would not use the pictures. The Army has authority over photographs and stories to protect operational security, not because the topic might embarrass them.

“I’m going to tell the contractor we had this conversation, John,” the major said.

“I understand.”

I hung up and a very chastened lieutenant drove me to the press barracks. Three hours later he dropped me off with soldiers of the 1-26th Infantry Regiment deploying to Tereyzai. Before I stepped out of his pickup, the lieutenant told me to destroy the photographs. I deleted the photographs from my camera, neglecting to mention I had already downloaded them to my laptop.

I want to work on the base but not in the smoking place.

I know people, when they start work at the base, after six months they are sick. Coughing. Chest problems. Breathing. They talk about the smoking place and how it smells. These same people I saw when they were not employed. They were healthy. Then they got jobs on the base and came back sick.

—Masjdi, 26, unemployed, Bagram Village

Combat Outpost Tereyzai lies in southern Khost Province in Tereyzai District, about a two-hour drive from the Pakistan border. The mission of the American soldiers there included intercepting, killing or capturing insurgent fighters. U.S. forces were also helping to develop the administrative capacity of the district government. In addition, U.S. soldiers assisted in training local Afghan police and Afghan border security patrols, and worked alongside them.

By the time I arrived, U.S. forces and their Afghan counterparts had so successfully disrupted the flow of arms that they rarely discovered hidden caches of Kalashnikov rifles and other weapons anymore. The Afghans were pleased, but the U.S. soldiers were bored. They wanted to “kill bad guys,” but few of them had fired a single shot. Many fretted that they might not shoot any insurgents before they returned to the states in December.

Yet the war was not finished. Roadside bombs remained a constant threat and forced military convoys to move as slowly as the traffic in Kabul. The insurgents were like gnats buzzing about the soldiers’ heads. Diminished but still a deadly, determined nuisance.

My first night at Tereyzai, I sat with off-duty soldiers at wobbly picnic tables outside the mess hall. The soldiers drank soft drinks and water and threw the empty cans and plastic bottles into a rusty barrel burning with other trash—Styrofoam mess hall trays, the plastic wrap from MREs. I threw my trash in the flaming barrel along with everyone else.

“When the shit bags burn, it sucks,” the interpreter said.

“Burning plastic bags is way bad,” one American officer at Tereyzai acknowledged. “I don’t know why we can’t recycle. Probably too expensive. You’d have a hard time convincing anyone to put garbage convoys on the road, where they are at additional risk of IED ambush and put an additional strain on already limited tactical resources.”

In other words, burning was just the easiest and cheapest thing to do in a screwed-up, throwaway country like Afghanistan.

From a guard tower not far from the picnic tables, I could see the Tereyzai burn pit about a city block outside the base. Wind swirled around the pit carrying black ash toward the mountains behind it. Some Afghan interpreters quartered below the guard tower near a gym told me they often smelled it.

“Sometimes the burn pit blows in our direction,” one said. He could distinguish the different odors, especially the plastic, zip-lock Waste Alleviation and Gelling (WAG) bags used to dispose of human waste.

“When the shit bags burn, it sucks,” the interpreter said.

A civilian contractor listening to our conversation said he had been “FOB hopping” for a year as an electrician. When he was at Combat Outpost Bak, he saw dogs walk into flaming burn pits tearing at the discarded plastic wrap of MRE packages. The dog’s dirt-encrusted fur, he said, acted as a fire retardant.

“We called them hell hounds.”

The next morning, a military police officer and two privates tossed bags of garbage into the back of a pickup already stacked with trash from other parts of the outpost. I joined them for the short drive to the burn pit.

The bitter stink of charred tin and aluminum, melting plastic and other throat-tightening odors gave me an immediate, sharp headache. The MP said no one disposes of garbage after 2 p.m. because the wind changes direction and the smoke would blow toward the base. I told him what the interpreter had said about the funk that sometimes settled over his barrack.

“We don’t control the wind,” the MP said.

He tossed the last garbage bag into the pit and hurried back to the truck and cranked up his window. White smoke washed over us.

“Cover your face,” he said. “That was just a bag of shit.”

In the evening, long after the American soldiers have completed their patrol, long after they found Army boots, desert camouflage pants and other contraband among some vendors unwise enough to stay open, the shopkeepers in Bagram Village close their doors for the night, bolting them shut with heavy rusty locks that have been in their families for generations.

On their way home, they smell it. The black and green smoke carrying with it the odor of plastic. The air has always been here, the shopkeepers say, but it never bothered the people. With war, the air affects people badly. The plastic smell belongs to the wind. No one will control which way it moves or who it touches.

Notes:

On July 25, 2011, in response to a letter from Guernica editors, the Army agreed that the Fort Salerno burn pit photos did not pose a security risk and could be published.

Research support was provided by The Investigative Fund at The Nation Institute, which also supported the J. Malcolm Garcia story, “Smoke Signals,” in the September 1, 2011 issue of The Oxford American. The story profiles the lives of two widows whose husbands died from their exposure to burn pits.

J. Malcolm Garcia is a contributing writer for Guernica. His writing has been anthologized in Best American Travel Writing and Best American Nonrequired Reading.